You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

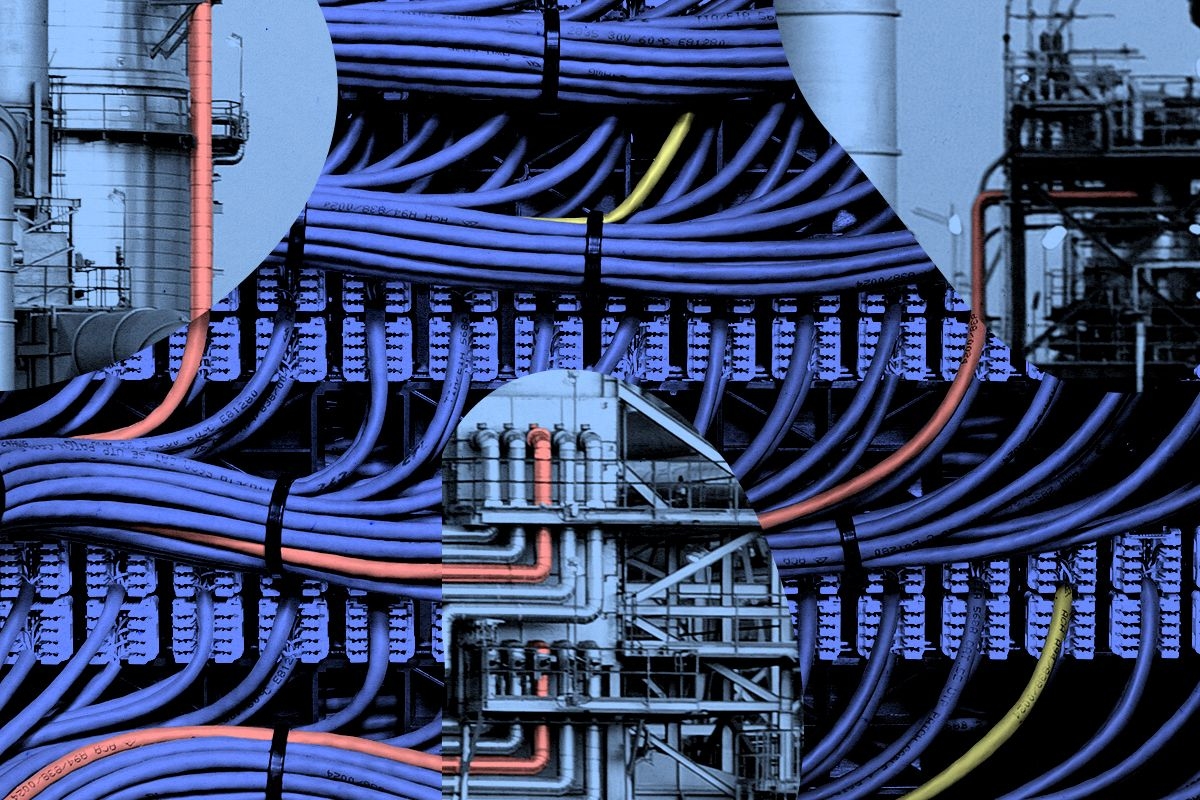

Federal energy regulators directed the country’s largest grid to make its rules make sense.

Federal energy regulators don’t want utilities and electricity market rules getting in the way of data centers connecting directly to power plants.

That was the consensus message from both Republican and Democratic commissioners on the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission Thursday, when it issued its long-awaited order on co-location in PJM Interconnection, the country’s largest electricity market, covering the Mid-Atlantic and Midwest.

The question is a holdover from last year, when Amazon struck a deal with independent power producer Talen Energy to co-locate an Amazon Web Services data center with the Susquehanna nuclear plant in Pennsylvania. Amazon eventually amended the deal to a more traditional power purchase agreement after failing to win regulatory approval for a behind-the-meter arrangement. Constellation, which owns a number of nuclear power plants in the PJM territory, had asked FERC to force PJM to adopt co-location rules and prevent what it saw as utilities obstructing co-location projects.

More broadly, though, the dispute is between independent power plants and their owners and utilities who build and operate the transmission grid. The latter want the former to essentially pay full freight for grid services for co-located power plants, even if they are largely or exclusively serving a single customer — such as, let’s say, a data center. Even co-located loads still incur substantial grid costs, utilities have argued, which should be paid for in their entirety.

Co-location has become attractive lately as a way to get data centers online faster and limit expensive grid upgrades that could drive up costs for everyone on the grid. Up until now, though, PJM didn’t really have a way to determine the distribution of costs and responsibilities when some or all of a new demand source is served by a co-located generator — and it wasn’t really in a particular rush to set one up, FERC said.

“The Commission finds that PJM’s tariff does not appear to sufficiently address the rates, terms and conditions of service that apply to co-location arrangements,” FERC said in its order. “The absence of this information may leave generators and load unable to determine what steps they can take to set up co-location arrangements of various configurations, and how to do so in an acceptable way.”

The commission was unanimous in its order, showing that despite the increased partisanship of regulatory politics in Donald Trump’s Washington, FERC is still operating under its traditional consensus-based approach. The consensus also shows the high level of dissatisfaction across the political spectrum with rising electricity prices, and specifically with PJM, which has combined rising prices with a clogged interconnection process and concerns about reliability.

“If a new large load wants to connect directly with a power plant and operate in a way that lowers grid costs, we should let it. If the current rules don’t let this work in a way that’s fair for everyone,” said Commissioner David Rosner, a Democrat. “We should change those rules so we can deliver the savings that consumers need and ensure reliable electricity for everybody.”

In its order, the commission asked PJM to come up with new arrangements that will allow transmission costs to scale with actual usage of the transmission system.

To do so, the new rules will have to reflect the actual usage of the transmission system of a co-located data center or other large load, Rosner explained.

He gave the example of a 1,000-megawatt data center co-located with a new 900-megawatt power plant. Its draw from the grid would be 100 megawatts, but “under PJM status quo rules,” Rosner said, “the data center needs to take the full 1,000 megawatts of front-of-meter transmission service from the grid, despite being directly connected to the co-located power plant.”

With the new options FERC is mandating PJM come up with, “the data center will now have the option to purchase what we call firm contract demand to take just 100 megawatts of firm service,” Rosner said, which will help cut costs across the board, he added.

The order also touches on the other hottest subject in grid policy today: flexibility. Because PJM will no longer be required to plan transmission or assure it has capacity for directly-connected loads, Rosner said, a big customer will have to accept the risk of being curtailed “if its usage exceeds what it’s contracted for in advance.”

The renewables industry cheered the order, especially the message that PJM needs to embrace flexibility and enable new generation and load to get online quickly.

“PJM needs to heed FERC’s message that grid flexibility enables speed, affordability, and reliability. As PJM proposes new rules to enable fast-tracking large load interconnections, it should prioritize the advanced energy technologies that are quickest to build and enable flexibility,” Jon Gordon, policy director at Advanced Energy United, said in a statement.

Independent power producers — i.e. the companies that own that power plants — also seemed happy with what the commission had to say. Talen, Constellation Energy, and Vistra Energy, all of whom have substantial footprints in PJM, saw their share prices rise at least 3% in early Thursday trading.

Thursday’s order comes as “large load interconnection” — i.e. data centers hooking up to the grid — dominates the energy regulatory discussion. Secretary of Energy Chris Wright has asked FERC to come up with new rules early next year to speed up interconnection without jacking up consumer electricity prices. At the same time, PJM’s market is under stress, with another capacity auction this week resulting in yet another round of record-setting payments to generators — plus, this time, a failure to secure its typical margin over and above its minimum projected capacity needed to ensure future reliability.

PJM is working on its own new set of rules to connect large loads without large price impacts, a process that has so far resulted in not much, as the market’s board has yet to agree on a proposal to bring to FERC.

Beating up on PJM was a bipartisan affair Thursday morning.

“The order recognizes that PJM existing transmission services are insufficient in that they do not recognize the controllable nature of co-location arrangement’s,” the commission’s Republican Chair Laura Swett said in her statement at Thursday’s meeting.

“Flexible options for co-located load means carving a path for minimizing expensive and time-intensive network upgrades in circumstances where they’re not needed,” Commissioner Lindsay See, another Republican appointee, said.

Rosner’s statement echoed his colleagues’, arguing that the existing PJM rates and contracts are “unjust and unreasonable” because they do not “contain provisions addressing with sufficient clarity or consistency the rates, terms and conditions of service that apply to interconnection customers serving co-located load and eligible customers taking transmission service on behalf of co-located load.”

He also addressed the electricity market’s board directly: “In my opinion, PJM board, tomorrow, once you’ve read this order, would be a great day to file this with us,” Rosner said.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

It starts — but doesn’t end — with the Strait of Hormuz.

For the second time in a year, the United States and Israel have launched a major aerial assault on Iran. Strikes were reported across the country early Saturday, targeting Iranian leadership and military infrastructure. In retaliation, Iran has launched attacks on Israel and Gulf nations allied with the U.S., with several of the targets appearing to be American military installations. “The United States military is undertaking a massive and ongoing operation,” President Trump said in a video posted to Truth Social explaining his rationale for launching the war.

While the conflict has quickly metastasized across the region, it has the potential to affect the entire world by disrupting the production and shipment of oil and natural gas.

Iran and its neighbors on the Persian Gulf are some of the largest oil and gas producers in the world and the country has long threatened to disrupt oil exports as an act of self-defense or retaliation from attack.

That may be already happening. According to data from Bloomberg, some oil tankers are pausing or turning around outside the vital Strait of Hormuz, a narrow, deep channel between Iran and Oman that connects the Persian Gulf to the Arabian Sea and thus to global markets in and bordering the Indian Ocean.

The strait has been “effectively closed,” according to a report from Tasnim, a semi-official news agency linked to the Iran Revolutionary Guard Corps. British naval officials also said they had “received multiple reports” of broadcasts that “have claimed that the Strait of Hormuz (SoH) has been closed.” And a European Union naval official told Reuters that the Iranian Revolutionary Guard had been broadcasting “no ship is allowed to pass the Strait of Hormuz” to ships in the area. Some tankers are still navigating the strait, according to marine tracking data from Kpler.

But it’s questionable whether Iran can actually maintain any attempted closure of the strait, whether by laying mines or directly threatening and attacking ships.

So far, U.S. attacks are “targeting, fairly heavily, naval assets and assets that are close to the Gulf,” Greg Brew, an analyst at the Eurasia Group, told me, which “suggests that they are trying to degrade Iran’s ability to disrupt energy traffic through the Strait of Hormuz.”

The U.S. is “trying to reduce the risks of Iranian effort to close the strait as part of this operation, rather than waiting to see if the Iranians escalate in that direction. The Iranians have responded by claiming that the strait has been closed. The problem for them now, though, is that they’ll have to enforce that threat.”

Closing the strait was a “tail risk” that had been roiling the oil market in the lead-up to Trump’s decision to launch the attack, Rory Johnston, petroleum analyst and author of Commodity Context, told me.

Global oil prices had gotten skittish over the past weeks, with the Brent crude benchmark getting as low at $66.30 per barrel in early February and getting near $73 per barrel on Friday. Brent prices approached $80 per barrel last June during the 12 Day War between Iran and Israel.

While the market could likely weather disruption to Iran’s own exports, jumpy behavior in the market was due to pricing in an enhanced risk of a region-wide calamity. Options traders especially were “attempting to hedge that enormous tail risk,” Johnston said, and “that was really moving the market.”

And even if the strait is not directly closed off by the Iranian military, ships may find it financially onerous to attempt the passage. “Insurers told ship owners on Saturday they would cancel policies and raise coverage prices for vessels travelling through the Gulf and Strait of Hormuz after the U.S. and Israel attacked Iran,” the Financial Times reported Saturday.

Another risk to the region’s oil sector is that Iran could retaliate by striking oil production and exporting infrastructure in neighboring countries, Johnston told me. “Right next door, you’ve got Iraq, you’ve got Saudi Arabia, and you’ve got the Emirates and others who collectively are more like 20 million barrels per day. And that is obviously a much bigger deal,” Johnston said, comparing their production to Iran’s own oil industry.

Of course, Iran is still a major exporter despite U.S. sanctions; in the days running up to the U.S. attack, it was shipping out around 3 million barrels per day from Kharg Island in the Strait of Hormuz, according to data from Bloomberg, almost triple its exports from equivalent dates in January and nearly its entire daily production.

Iran’s exports “had actually surged immediately ahead of what’s gone down over the past 24 hours,” Johnston told me. “In the past couple days, you’d seen a large surge of tankers departing Kharg Island, and the inventories on Kharg Island being drawn down, which is kind of what you would do if you expected that your exports were about to get disrupted.”

To the extent Iranian oil exports are cut off, that could be a big deal for China, which has become the number one destination for Middle East oil shipments. Beijing has been building up stockpiles of oil, likely preparing for the risk that sanctioned exporters like Iran and Venezuela would go off the market, as well as wider risks to exports from the Middle East.

“China is highly concerned over the military strikes against Iran,” the Chinese foreign ministry wrote on X. “China calls for an immediate stop of the military actions, no further escalation of the tense situation, resumption of dialogue and negotiation, and efforts to uphold peace and stability in the Middle East.”

Last year, China began to substantially increase its stockpiling of oil, going from 84,000 barrels per day to 430,000 barrels per day, some 83% of the growth of its imports, according to data and estimates from Rystad Energy and Erica Downs, a senior research scholar at the Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy.

While the U.S. is now far less reliant on oil exports from the Middle East, oil and gas is still a global market. If Middle Eastern oil and gas exports are disrupted, that will likely increase the price of energy — whether it’s gasoline, electricity, or even home heating — as American energy producers can sell their barrels and BTUs at higher prices globally.

It’s either reassure investors now or reassure voters later.

Investor-owned utilities are a funny type of company. On the one hand, they answer to their shareholders, who expect growing returns and steady dividends. But those returns are the outcome of an explicitly political process — negotiations with state regulators who approve the utilities’ requests to raise rates and to make investments, on which utilities earn a rate of return that also must be approved by regulators.

Utilities have been requesting a lot of rate increases — some $31 billion in 2025, according to the energy policy group PowerLines, more than double the amount requested the year before. At the same time, those rate increases have helped push electricity prices up over 6% in the last year, while overall prices rose just 2.4%.

Unsurprisingly, people have noticed, and unsurprisingly, politicians have responded. (After all, voters are most likely to blame electric utilities and state governments for rising electricity prices, Heatmap polling has found.) Democrat Mikie Sherrill, for instance, won the New Jersey governorship on the back of her proposal to freeze rates in the state, which has seen some of the country’s largest rate increases.

This puts utilities in an awkward position. They need to boast about earnings growth to their shareholders while also convincing Wall Street that they can avoid becoming punching bags in state capitols.

Make no mistake, the past year has been good for these companies and their shareholders. Utilities in the S&P 500 outperformed the market as a whole, and had largely good news to tell investors in the past few weeks as they reported their fourth quarter and full-year earnings. Still, many utility executives spent quite a bit of time on their most recent earnings calls talking about how committed they are to affordability.

When Exelon — which owns several utilities in PJM Interconnection, the country’s largest grid and ground zero for upset over the influx data centers and rising rates — trumpeted its growing rate base, CEO Calvin Butler argued that this “steady performance is a direct result of a continued focus on affordability.”

But, a Wells Fargo analyst cautioned, there is a growing number of “affordability things out there,” as they put it, “whether you are looking at Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware.” To name just one, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro said in a speech earlier this month that investor-owned utilities “make billions of dollars every year … with too little public accountability or transparency.” Pennsylvania’s Exelon-owned utility, PECO, won approval at the end of 2024 to hike rates by 10%.

When asked specifically about its regulatory strategy in Pennsylvania and when it intended to file a new rate case, Butler said that, “with affordability front and center in all of our jurisdictions, we lean into that first,” but cautioned that “we also recognize that we have to maintain a reliable and resilient grid.” In other words, Exelon knows that it’s under the microscope from the public.

Butler went on to neatly lay out the dilemma for utilities: “Everything centers on affordability and maintaining a reliable system,” he said. Or to put it slightly differently: Rate increases are justified by bolstering reliability, but they’re often opposed by the public because of how they impact affordability.

Of the large investor-owned utilities, it was probably Duke Energy, which owns electrical utilities in the Carolinas, Florida, Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio, that had to most carefully navigate the politics of higher rates, assuring Wall Street over and over how committed it was to affordability. “We will never waver on our commitment to value and affordability,” Duke chief executive Harry Sideris said on the company’s February 10 earnings call.

In November, Duke requested a $1.7 billion revenue increase over the course of 2027 and 2028 for two North Carolina utilities, Duke Energy Carolinas and Duke Energy Progress — a 15% hike. The typical residential customer Duke Energy Carolinas customer would see $17.22 added onto their monthly bill in 2027, while Duke Energy Progress ratepayers would be responsible for $23.11 more, with smaller increases in 2028.

These rate cases come “amid acute affordability scrutiny, making regulatory outcomes the decisive variable for the earnings trajectory,” Julien Dumoulin-Smith, an analyst at Jefferies, wrote in a note to clients. In other words, in order to continue to grow earnings, Duke needs to convince regulators and a skeptical public that the rate increases are necessary.

“Our customers remain our top priority, and we will never waver on our commitment to value and affordability,” Sideris told investors. “We continue to challenge ourselves to find new ways to deliver affordable energy for our customers.”

All in all, “affordability” and “affordable” came up 15 times on the call. A year earlier, they came up just three times.

When asked by a Jefferies analyst about how Duke could hit its forecasted earnings growth through 2029, Sideris zeroed in on the regulatory side: “We are very confident in our regulatory outcomes,” he said.

At the same time, Duke told investors that it planned to increase its five-year capital spending plan to $103 billion — “the largest fully regulated capital plan in the industry,” Sideris said.

As far as utilities are concerned, with their multiyear planning and spending cycles, we are only at the beginning of the affordability story.

“The 2026 utility narrative is shifting from ‘capex growth at all costs’ to ‘capex growth with a customer permission slip,’” Dumoulin-Smith wrote in a separate note on Thursday. “We believe it is no longer enough for utilities to say they care about affordability; regulators and investors are demanding proof of proactive behavior.”

If they can’t come up with answers that satisfy their investors, ultimately they’ll have to answer to the voters. Last fall, two Republican utility regulators in Georgia lost their reelection bids by huge margins thanks in part to a backlash over years of rate increases they’d approved.

“Especially as the November 2026 elections approach, utilities that fail to demonstrate concrete mitigants face political and reputational risk and may warrant a credibility discount in valuations, in our view,” Dumoulin wrote.

At the same time, utilities are dealing with increased demand for electricity, which almost necessarily means making more investments to better serve that new load, which can in the short turn translate to higher prices. While large technology companies and the White House are making public commitments to shield existing customers from higher costs, utility rates are determined in rate cases, not in press releases.

“As the issue of rising utility bills has become a greater economic and political concern, investors are paying attention,” Charles Hua, the founder and executive director of PowerLines, told me. “Rising utility bills are impacting the investor landscape just as they have reshaped the political landscape.”

Plus more of the week’s top fights in data centers and clean energy.

1. Osage County, Kansas – A wind project years in the making is dead — finally.

2. Franklin County, Missouri – Hundreds of Franklin County residents showed up to a public meeting this week to hear about a $16 billion data center proposed in Pacific, Missouri, only for the city’s planning commission to announce that the issue had been tabled because the developer still hadn’t finalized its funding agreement.

3. Hood County, Texas – Officials in this Texas County voted for the second time this month to reject a moratorium on data centers, citing the risk of litigation.

4. Nantucket County, Massachusetts – On the bright side, one of the nation’s most beleaguered wind projects appears ready to be completed any day now.