You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

The U.S. is too enmeshed in the global financial system for the rest of the world to solve climate change without us.

The United States is now staring down the barrel of what amounts to a full repeal of the Inflation Reduction Act’s energy tax credits and loan authorities. Not even the House Republicans who vocally defended the law, in the end, voted against President Trump’s “One Big, Beautiful Bill.” To be sure, there’s no final outcome yet — leading Republican senators don’t seem satisfied with the bill headed their way, and energy sector lobbyists are ready to push harder. But the fact that House Republicans were willing to walk away from billions of dollars of public spending for their districts and perhaps $1 trillion worth of economic growth is a flashing red sign that Trump’s politics have capsized the once-watertight argument that the IRA would be too important to American businesses and communities to be destroyed.

The Biden Administration touted the IRA as the United States’ marquee investment not just in reducing emissions and promoting economic development, but also in bringing back American manufacturing to compete against China in the market for advanced technologies. The Trump administration takes this apparent conflict with China seriously ― the threat of economic decoupling looms large ― but seems to have no desire to compete the way the Biden administration did. Rather than commit to the solar, wind, battery, grid, and electric vehicle investments that are laying the foundation for a manufacturing revival, the Trump administration has doubled down on the conjoined ideas that America should be self-sufficient and should play to its strengths: critical minerals, nuclear, natural gas, and even coal. Never mind that Trump’s tariff policy and his party’s deep cuts to energy-related spending will stop these plans, too, in their tracks. “Energy dominance” has always been a smokescreen ― of fossil fuels, by fossil fuels, for fossil fuels.

While Republicans attempt to shut down America’s entire scientific research apparatus, the rest of the world moves on. The demise of the Inflation Reduction Act would decisively surrender the global market for all types of commercialized clean energy sources (and nuclear energy, too) to Chinese companies. Chinese companies already dominate the input sectors for these technologies, whether it’s processing and refining mineral products such as polysilicon, gallium, and graphite, or producing infrastructure commodities such as steel and aluminum. The end of Biden’s climate and infrastructure laws will also leave the American car industry in the dust, as the rest of the world shifts gears toward purchasing more efficient and cheaper electric vehicles ― particularly Chinese brands such as BYD. (Ford’s CEO drives a Xiaomi electric vehicle and “doesn’t want to give it up.”) Consider it a sign of the times that Ethiopia recently banned the import of gas-powered vehicles. Electrification is in, combustion is burnt out.

It’s not just China that benefits. In November, the Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab at Johns Hopkins estimated that the repeal of the IRA leaves up to $80 billion in clean technology manufacturing investment opportunities for other countries to seize between now and 2032, the law’s intended sunset year. Those countries aren’t just the likely (read: wealthier) suspects such as Japan, South Korea, or the European Union. The abdication of U.S. leadership would also boost electric vehicle and battery manufacturing capacity in Morocco, Mexico, India, Indonesia, and elsewhere across Southeast Asia; solar power-related manufacturing further across Southeast Asia; and wind power-related manufacturing in Brazil, Mexico, South Africa, India, and Canada.

These countries won’t just benefit from investors looking to build outside the United States. A Trump-induced fall in American imports of these technologies and their inputs may also drive some degree of global disinflation, insofar as these countries can secure input goods no longer flowing into the American market at cheaper prices. The writing has been on the wall since the early Biden administration that failing to invest meant investing in failure. This is what the Trump administration is poised to do, to the detriment of American technological capabilities and standards of living.

Just because the United States might be dropping out of the race for global decarbonization, however, does not mean that the rest of the world can choose to ignore the United States in return. The Trump administration can still play spoiler with every other country’s efforts to decarbonize ― even China’s ― for one overarching reason: the mighty dollar. The United States may be hemorrhaging the political capital that coordinating the energy transition requires, but it still controls the currency of decarbonization itself.

It’s hard to overstate how central the management of the U.S. dollar is to the management of global decarbonization. Let’s sketch out some of the key dynamics. First, the dollar is the world’s primary trade currency. Because most global trade is denominated and invoiced in dollars, fluctuations in the value of the dollar relative to the value of other currencies will affect the price of importing both essential commodities and capital goods in other countries. Any volatility in the prices of oil, critical minerals, food, or machinery ― including the inputs to energy systems ― is most likely measured in a currency that every other country needs to earn through trade or borrow from investors. Efforts to denominate commodity trade in other currencies, such as the Chinese renminbi, are not likely to scale up rapidly, however, thanks to the network effect of the dollar system: Market actors will only ditch the dollar if most of their counterparties do.

Second, then, the dollar is the world’s dominating financial currency. Countries seeking foreign investment must issue debt at rates and on terms that foreign investors, many of whom measure their returns in dollars, judge as safe relative to the returns on U.S. Treasury bonds, conventionally the world’s premier “safe asset.” How the U.S. Federal Reserve moves interest rates influences how every other central bank does; higher rates in the U.S. usually push up Treasury bond yields and, as other central banks also raise rates or stockpile dollars, make borrowing for investment and for refinancing debt more expensive across the whole world ― particularly for large-scale energy and adaptation infrastructure projects. The U.S. Federal Reserve also manages the dollar swap lines and repurchase (or “repo”) facilities that provide dollar liquidity to the rest of the world during a financial crisis, as in the Great Recession and the subsequent Eurozone financial crisis, or a sudden dollar cash shortage, as in 2019.

Finally, the United States maintains a comprehensive sanctions regime that operates through cross-border dollar payments systems and “clearing-house” facilities such as SWIFT, which processes interbank payments, and CHIPS, which handles over 90% of all dollar-denominated transactions globally. When the United States wants to cut target companies and whole countries out of the dollar financial system, it prevents SWIFT from processing targeted entities’ cross-border transactions and U.S.-based financial institutions from accepting them.

The Obama administration and first Trump administration used U.S. control over SWIFT and CHIPS to administer sanctions against Iran, and the Biden administration did the same to Russia. The U.S. Departments of Treasury and Commerce also administer what’s known as a “secondary sanctions” regime that imposes these financial penalties on unrelated third-parties that violate initial sanctions. And the Department of Commerce enforces export controls that restrict technology transfer to foreign targets. The Biden administration combined these authorities to limit the ability of both U.S. and foreign companies to export certain technologies to targeted Chinese companies.

Perhaps ironically, some of these dynamics don’t bite the way they used to during the Biden administration, when the dollar was expensive relative to other currencies. Trump’s inflationary and growth-destroying budget, trigger-happy tariffs, and neglect of the fracking sector have driven a sharp depreciation in the dollar and destabilized the market for U.S. Treasury debt. Some cuts to U.S. interest rates are likely given the elevated probability of a recession. All of these factors ― undeniably a bad look for the United States ― should support emerging market financial conditions by lowering the cost of commodity imports, raising the attractiveness of sovereign debt to foreign investors, and help stave off potential debt crises.

But easier global financial conditions in the short term do not diminish the threat the Trump administration continues to pose to global economic stability. The danger that the Trump administration expands the American sanctions regime implemented via the global dollar invoicing system and export controls remains undiminished. What’s more, the tension between the president and Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell should alert foreign central banks that their access to the American dollar liquidity facilities is ultimately contingent on the Federal Reserve’s independence from Trump’s influence. During the first Trump administration, the European Union and China alike started strategizing how to derisk their dependence on the dollar; U.S. policymakers should not be surprised if those governments are now dusting off those playbooks.

The dollar’s dominance is in part an effect of the gargantuan size of the U.S. consumer market. Trump’s tariff threats had governments across the world scrambling to cut deals with the United States to preserve their market access ― including by promising to purchase U.S. natural gas.

The view outside the U.S. seems to be that there is no easy replacement for the U.S. consumer. As the Australian Strategic Policy Institute put it, “US household spending in 2023 reached $19 trillion, double the level of the European Union and almost three times that of China. … there are no obvious markets to replace [U.S. consumers].” Indian journalist M. Rajshekhar notes that China, too, needs external markets to absorb its products, and that it cannot count on other Global South countries to let Chinese goods flood their markets. Americans are the motor that keeps the global economy spinning.

The inability to sell goods to the United States is a threat to decarbonization abroad not just because it gives Trump an avenue to hawk natural gas, but also because U.S. consumer spending provides the world with a source of the dollars with which decarbonization is financed in the first place. And to the extent that the IRA would have supported U.S. consumer demand for clean energy technologies and electric vehicles, its de facto repeal ― while a source of potential disinflation for Global South producers ― snuffs out a key demand signal for the production of inputs to those sectors across the Global South.

Where the Global South’s clean energy transition is concerned, natural gas unfortunately remains an important alternative to coal in the absence of widespread renewable energy deployment. The U.S. is the world’s largest exporter of liquified natural gas, the use of which has doubled since 2009 as global demand for the fuel rose sharply. Countries across Europe and Asia depend on U.S. gas for domestic power and industrial uses ― particularly after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Large energy importing countries like India increasingly rely on gas to meet energy demand spikes. Over the longer term, industry leaders expect LNG demand to rise 60% by 2040, particularly on the back of persistent Asian demand. Although planned U.S. LNG export capacity is already on track to double between now and 2028, the Trump administration is supporting the buildout of even more capacity to meet this expected global demand.

Becoming dependent on “molecules of U.S. freedom” for industrial growth and for transitioning off of coal may once have seemed like a smart decision across emerging markets, particularly when prices were lower. But it has now left dependent Global South countries uniquely vulnerable to energy import price and power market shocks caused by erratic U.S. policy and volatile (dollar-denominated) natural gas prices. Will the gas-dependent countries in Europe and Asia be able to access enough Chinese imports, invest sufficiently in local clean technology, and kick their LNG fix in time to meet their emissions reduction goals? Europe might; for the rest, this question is one worth following over the coming years.

The truth is that the United States has always had a unique opportunity to weaponize these aspects of dollar dominance in the interest of playing global spoilsport. As Chen Chris Gong, a researcher at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, argues in her forthcoming (not yet peer-reviewed) paper on “The geoeconomics of transitioning to the post-fossil world,” Global South countries have an urgent reason to decarbonize built into their politics, whether their governments recognize it or not. So long as much of the Global South is dependent on imported fossil fuels for energy, “local people’s livelihood and firms’ survival are made vulnerable to compound cycles of dollar capital flow and cycles of basic commodity trade.” If the Global South cannot fully avoid the United States, their governments can at least sidestep it. Countries powered by clean energy, importing less fuel, and generating their own power are far more insulated from the dollar cycle and the dollar system, simple as that.

In contrast, as Gong highlights, the only incentives for the United States to pursue decarbonization come from the pressure of competing with China ― a competition that Republicans, for all their bluster, may not actually want to win ― or the pressure of mass consumer demand for a clean economy ― for which Democrats are not exactly fighting tooth and nail ― and the profits both promise. It’s darkly funny that the Inflation Reduction Act’s defenders are seizing on these exact reasons in their attempts to protect the law in the Senate when neither sufficiently moved House Republicans to reconsider.

For posterity, then, we should add another reason, even if it won’t convince Republicans to change tack: The looming repeal of the Inflation Reduction Act portends a future where Trump and his Republican party happily use their control over the global economy to drag the rest of the world down with the United States. “Energy dominance” may always have been formless bluster, but the United States’ financial dominance remains sharp enough to cut ― if not global emissions, then global standards of living.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Batteries can only get so small so fast. But there’s more than one way to get weight out of an electric car.

Batteries are the bugaboo. We know that. Electric cars are, at some level, just giant batteries on wheels, and building those big units cheaply enough is the key to making EVs truly cost-competitive with fossil fuel-burning trucks and cars and SUVs.

But that isn’t the end of the story. As automakers struggle to lower the cost to build their vehicles amid a turbulent time for EVs in America, they’re looking for any way to shave off a little expense. The target of late? Plain old wires.

Last month, when General Motors had to brace its investors for billions in losses related to curtailing its EV efforts and shifting factories back to combustion, it outlined cost-saving measures meant to get things moving in the right direction. While much of the focus was on using battery chemistries like lithium ion phosphate, otherwise known as LFP, that are cheaper to build, CEO Mary Barra noted that the engineers on every one of the company’s EVs were working “to take out costs beyond the battery,” of which cutting wiring will be a part.

They are not alone in this obsession. Coming into a do-or-die year with the arrival of the R2 SUV, Rivian said it had figured out how to cut two miles of wires out of the design, a coup that also cuts 44 pounds from the vehicle’s weight (this is still a 5,000-pound EV, but every bit counts). Ford has become obsessed with figuring out smarter and cheaper ways for its money-hemorrhaging EV division to build cars; the company admitted, after tearing down a Tesla Model 3 to look inside, that its Mustang Mach-E EV had a mile of extra and possibly unnecessary wiring compared to its rival.

A bunch of wires sounds like an awfully mundane concern for cars so sophisticated. But while every foot adds cost and weight, the obsession with stripping out wiring is about something deeper — the broad move to redefine how cars are designed and built.

It so happens that the age of the electric vehicle is also the age of the software-defined car. Although automobiles were born as purely mechanical devices, code has been creeping in for decades, and software is needed to manage the computerized fuel injection systems and on-board diagnostic systems that explain why your Check Engine light is illuminated. Tesla took this idea to extremes when it routed the driver’s entire user interface through a giant central touchscreen. This was the car built like a phone, enabling software updates and new features to be rolled out years after someone bought the car.

As Tesla ruled the EV industry in the 2010s, the smartphone-on-wheels philosophy spread. But it requires a lot of computing infrastructure to run a car on software, which adds complexity and weight. That’s why carmakers have spent so much time in the past couple of years talking about wires. Their challenge (among many) is to simplify an EV’s production without sacrificing any of its capability.

Consider what Rivian is attempting to do with the R2. As InsideEVs explains, electric cars have exploded in their need for electronic control units, the embedded computing brains that control various systems. Some models now need more than 100 to manage all the software-defined components. Rivian managed to sink the number to just seven, and thus shave even more cost off the R2, through a “zonal” scheme where the ECUs control all the systems located in their particular region of the vehicle.

Compared to an older, centralized system that connects all the components via long wires, the savings are remarkable. As Rivian chief executive RJ Scaringe posted on X: “The R2 harness improves massively over the R1 Gen 2 harness. Building on the backbone of our network architecture and zonal ECUs, we focused on ease of install in the plant and overall simplification through integrated design — less wires, less clips and far fewer splices!”

Legacy automakers, meanwhile, are racing to catch up. Even those that have built decent-selling quality EVs to date have not come close to matching the software sophistication of Tesla and Rivian. But they have begun to see the light — not just about fancy iPads in the cockpit, but also about how the software-defined vehicle can help them to run their factories in a simpler and cheaper way.

How those companies approach the software-defined car will define them in the years to come. By 2028, GM hopes to have finished its next-gen software platform that “will unite every major system from propulsion to infotainment and safety on a single, high-speed compute core,” according to Barra. The hope is that this approach not only cuts down on wiring and simplifies manufacturing, but also makes Chevys and Cadillacs more easily updatable and better-equipped for the self-driving future.

In that sense, it’s not about the wires. It’s about all the trends that have come to dominate electric vehicles — affordability, functionality, and autonomy — colliding head-on.

Europeans have been “snow farming” for ages. Now the U.S. is finally starting to catch on.

February 2015 was the snowiest month in Boston’s history. Over 28 days, the city received a debilitating 64.8 inches of snow; plows ran around the clock, eventually covering a distance equivalent to “almost 12 trips around the Equator.” Much of that plowed snow ended up in the city’s Seaport District, piled into a massive 75-foot-tall mountain that didn’t melt until July.

The Seaport District slush pile was one of 11 such “snow farms” established around Boston that winter, a cutesy term for a place that is essentially a dumpsite for snow plows. But though Bostonians reviled the pile — “Our nightmare is finally over!” the Massachusetts governor tweeted once it melted, an event that occasioned multiple headlines — the science behind snow farming might be the key to the continuation of the Winter Olympics in a warming world.

The number of cities capable of hosting the Winter Games is shrinking due to climate change. Of 93 currently viable host locations, only 52 will still have reliable winter conditions by the 2050s, researchers found back in 2024. In fact, over the 70 years since Cortina d’Ampezzo first hosted the Olympic Games in 1956, February temperatures in the Dolomites have warmed by 6.4 degrees Fahrenheit, according to Climate Central, a nonprofit climate research and communications group. Italian organizers are expected to produce more than 3 million cubic yards of artificial snow this year to make up for Mother Nature’s shortfall.

But just a few miles down the road from Bormio — the Olympic venue for the men’s Alpine skiing events as well as the debut of ski mountaineering next week — is the satellite venue of Santa Caterina di Valfurva, which hasn’t struggled nearly as much this year when it comes to usable snow. That’s because it is one of several European ski areas that have begun using snow farming to their advantage.

Like Ruka in Finland and Saas-Fee in Switzerland, Santa Caterina plows its snow each spring into what is essentially a more intentional version of the Great Boston Snow Pile. Using patented tarps and siding created by a Finnish company called Snow Secure, the facilities cover the snow … and then wait. As spring turns to summer, the pile shrinks, not because it’s melting but because it’s becoming denser, reducing the air between the individual snowflakes. In combination with the pile’s reduced surface area, this makes the snow cold and insulated enough that not even a sunny day will cause significant melt-off. (Neil DeGrasse Tyson once likened the phenomenon to trying to cook an entire potato with a lighter; successfully raising the inner temperature of a dense snowball, much less a gigantic snow pile, requires more heat.)

Shockingly little snow melts during storage. Snow Secure reports a melt rate of 8% to 20% on piles that can be 50,000 cubic meters in size, or the equivalent of about 20 Olympic swimming pools. When autumn eventually returns, ski areas can uncover their piles of farmed snow and spread it across a desired slope or trail using snowcats, specialized groomers that break up and evenly distribute the surface. For Santa Caterina, the goal was to store enough to make a nearly 2-mile-long cross-country trail — no need to wait for the first significant snowfall of the season, which creeps later and later every year.

“In many places, November used to be more like a winter month,” Antti Lauslahti, the CEO of Snow Secure, told me. “Now it’s more like a late-autumn month; it’s quite warm and unpredictable. Having that extra few weeks is significant. When you cannot open by Thanksgiving or Christmas, you can lose 20% to 30% of the annual turnover.”

Though the concept of snow farming is not new — Lauslahti told me the idea stems from the Finnish tradition of storing snow over the summer beneath wood chips, once a cheap byproduct of the local logging industry — the company's polystyrene mat technology, which helps to reduce summer melt, is. Now that the technique is patented, Snow Secure has begun expanding into North America with a small team. The venture could prove lucrative: Researchers expect that by the end of the century, as many as 80% of the downhill ski areas in the U.S. will be forced to wait until after Christmas to open, potentially resulting in economic losses of up to $2 billion.

While there have been a few early adopters of snow farming in Wisconsin, Utah, and Idaho, the number of ski areas in the United States using the technique remains surprisingly low, especially given its many other upsides. In the States, the most common snow management system is the creation of artificial snow, which is typically water- and energy-intensive. Snow farming not only avoids those costs — which can also have large environmental tolls, particularly in the water-strapped West — but the super-dense snow farming produces is “really ideal” for something like the Race Centre at Canada’s Sun Peaks Resort, where top athletes train. Downhill racers “want that packed, harder, faster snow,” Christina Antoniak, the area’s director of brand and communications, told me of the success of the inaugural season of snow farming at Sun Peaks. “That’s exactly what stored snow produced for that facility.”

The returns are greatest for small ski areas, which are also the most vulnerable to climate change. While the technology is an investment — Antoniak ballparked that Sun Peaks spent around $185,000 on Snow Secure’s siding — the money goes further at a smaller park. At somewhere like Park City Mountain in Utah, stored snow would cover only a small portion of the area’s 140 miles of skiable routes. But it can make a major difference for an area down the road like the Soldier Hollow Nordic Center, which has a more modest 20 miles of cross-country trails.

In fact, the 2025-2026 winter season will be the Nordic Center’s first using Snow Secure’s technology. Luke Bodensteiner, the area’s general manager and chief of sport, told me that alpine ski areas are “all very curious to see how our project goes. There is a lot of attention on what we do, and if it works out satisfactorily, we might see them move into it.”

Ensuring a reliable start to the ski season is no small thing for a local economy; jobs and travel plans rely on an area being open when it says it will be. But for the Soldier Hollow Nordic Center, the stakes are even higher: The area is one of the planned host venues of the 2034 Salt Lake City Winter Games. “Based on historical weather patterns, our goal is to be able to make all the snow that we need for the entire Olympic trail system in two weeks,” Bodensteiner said, adding, “We envision having four or five of these snow piles around the venue in the summer before the Olympic Games, just to guarantee — in a worst case scenario — that we’ve got snow on the venue.”

Antoniak, at Canada’s Sun Peaks, also told me that their area has been a bit of a “guinea pig” when it comes to snow farming. “A lot of ski areas have had their eyes on Sun Peaks and how [snow farming is] working here,” she told me. “And we’re happy to have those conversations with them, because this is something that gives the entire industry some more resiliency.”

Of course, the physics behind snow farming has a downside, too. The same science saving winter sports is also why that giant, dirty pile of plowed snow outside your building isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Current conditions: A train of three storms is set to pummel Southern California with flooding rain and up to 9 inches mountain snow • Cyclone Gezani just killed at least four people in Mozambique after leaving close to 60 dead in Madagascar • Temperatures in the southern Indian state of Kerala are on track to eclipse 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

What a difference two years makes. In April 2024, New York announced plans to open a fifth offshore wind solicitation, this time with a faster timeline and $200 million from the state to support the establishment of a turbine supply chain. Seven months later, at least four developers, including Germany’s RWE and the Danish wind giant Orsted, submitted bids. But as the Trump administration launched a war against offshore wind, developers withdrew their bids. On Friday, Albany formally canceled the auction. In a statement, the state government said the reversal was due to “federal actions disrupting the offshore wind market and instilling significant uncertainty into offshore wind project development.” That doesn’t mean offshore wind is kaput. As I wrote last week, Orsted’s projects are back on track after its most recent court victory against the White House’s stop-work orders. Equinor's Empire Wind, as Heatmap’s Jael Holzman wrote last month, is cruising to completion. If numbers developers shared with Canary Media are to be believed, the few offshore wind turbines already spinning on the East Coast actually churned out power more than half the time during the recent cold snap, reaching capacity factors typically associated with natural gas plants. That would be a big success. But that success may need the political winds to shift before it can be translated into more projects.

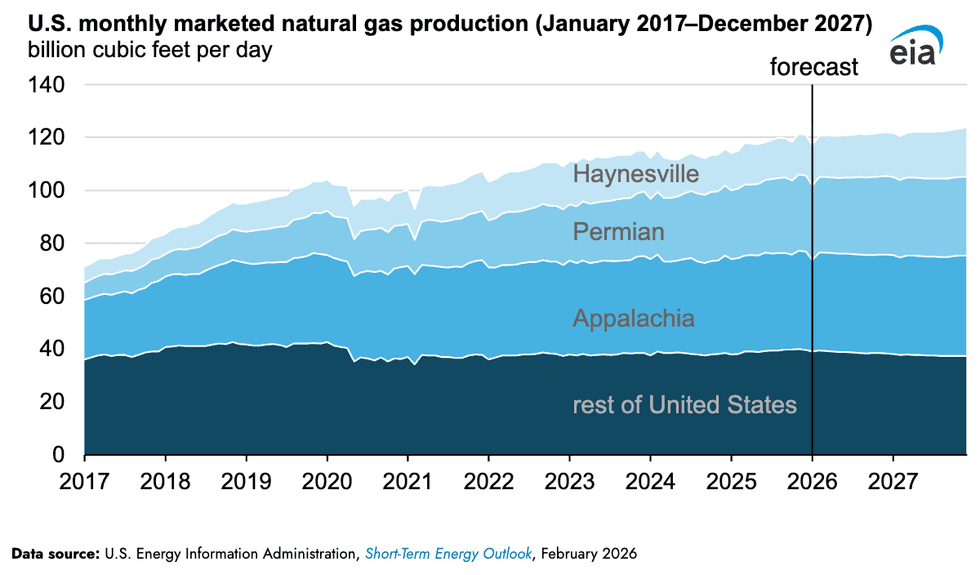

President Donald Trump’s “drill, baby, drill” isn’t moving American oil extractors, whose output is set to contract this year amid a global glut keeping prices low. But production of natural gas is set to hit a record high in 2026, and continue upward next year. The Energy Information Administration’s latest short-term energy outlook expects natural gas production to surge 2% this year to 120.8 billion cubic feet per day, from 118 billion in 2025 — then surge again next year to 122.3 billion cubic feet. Roughly 69% of the increased output is set to come from Appalachia, Louisiana’s Haynesville area, and the Texas Permian regions. Still, a lot of that gas is flowing to liquified natural gas exports, which Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin explained could raise prices.

The U.S. nuclear industry has yet to prove that microreactors can pencil out without the economies of scale that a big traditional reactor achieves. But two of the leading contenders in the race to commercialize the technology just crossed major milestones. On Friday, Amazon-backed X-energy received a license from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to begin commercial production of reactor fuel high-assay low-enriched uranium, the rare but potent material that’s enriched up to four times higher than traditional reactor fuel. Due to its higher enrichment levels, HALEU, pronounced HAY-loo, requires facilities rated to the NRC’s Category II levels. While the U.S. has Category I facilities that handle low-enriched uranium and Category III facilities that manage the high-grade stuff made for the military, the country has not had a Category II site in operation. Once completed, the X-energy facility will be the first, in addition to being the first new commercial fuel producer licensed by the NRC in more than half a century.

On Sunday, the U.S. government airlifted a reactor for the first time. The Department of Defense transported one of Valar Atomics’ 5-megawatt microreactors via a C-17 from March Air Reserve Base in California to Hill Air Force Base in Utah. From there, the California-based startup’s reactor will go to the Utah Rafael Energy Lab in Orangeville, Utah, for testing. In a series of posts on X, Isaiah Taylor, Valar’s founder, called the event “a groundbreaking unlock for the American warfighters.” His company’s reactor, he said, “can power 5,000 homes or sustain a brigade-scale” forward operating base.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

After years of attempting to sort out new allocations from the dwindling Colorado River, negotiators from states and the federal government disbanded Friday without a plan for supplying the 40 million people who depend on its waters. Upper-basin states Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico have so far resisted cutting water usage when lower-basin states California, Arizona, and Nevada are, as The Guardian put it, “responsible for creating the deficit” between supply and demand. But the lower-basin states said they had already agreed to substantial cuts and wanted the northern states to share in the burden. The disagreement has created an impasse for months; negotiators blew through deadlines in November and January to come up with a solution. Calling for “unprecedented cuts” that he himself described as “unbelievably harsh,” Brad Udall, senior water and climate research scientist at Colorado State University’s Colorado Water Center, said: “Mother Nature is not going to bail us out.”

In a statement Friday, Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum described “negotiations efforts” as “productive” and said his agency would step in to provide guidelines to the states by October.

Europe’s “regulatory rigidity risks undermining the momentum of the hydrogen economy. That, at least, is the assessment of French President Emmanuel Macron, whose government has pumped tens of billions of euros into the clean-burning fuel and promoted the concept of “pink hydrogen” made with nuclear electricity as the solution that will make energy technology take off. Speaking at what Hydrogen Insight called “a high-level gathering of CEOs and European political leaders,” Macron, who is term-limited in next year’s presidential election, said European rules are “a crazy thing.” Green hydrogen, the version of the fuel made with renewable electricity, remains dogged by high prices that the chief executive of the Spanish oil company Repsol said recently will only come down once electricity rates decrease. The Dutch government, meanwhile, just announced plans to pump 8 billion euros, roughly $9.4 billion, into green hydrogen.

Kazakhstan is bringing back its tigers. The vast Central Asian nation’s tiger reintroduction program achieved record results in reforesting an area across the Ili River Delta and Southern Balkhash region, planting more than 37,000 seedlings and cuttings on an area spanning nearly 24 acres. The government planted roughly 30,000 narrow-leaf oleaster seedlings, 5,000 willow cuttings, and about 2,000 turanga trees, once called a “relic” of the Kazakh desert. Once the forests come back, the government plans to eventually reintroduce tigers, which died out in the 1950s.