This article is exclusively

for Heatmap Plus subscribers.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Plus more of the week’s biggest renewable energy fights.

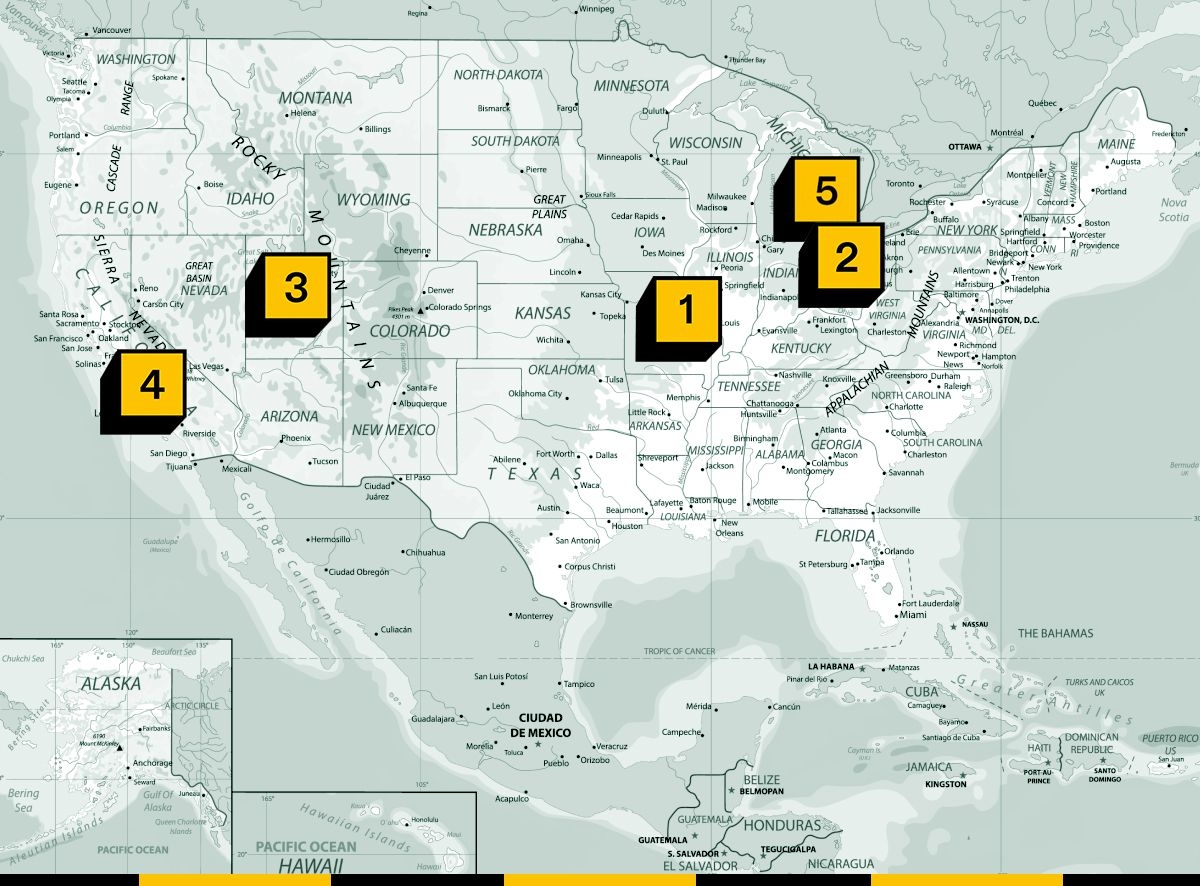

Cole County, Missouri – The Show Me State may be on the precipice of enacting the first state-wide solar moratorium.

Clark County, Ohio – This county has now voted to oppose Invenergy’s Sloopy Solar facility, passing a resolution of disapproval that usually has at least some influence over state regulator decision-making.

Millard County, Utah – Here we have a case of folks upset about solar projects specifically tied to large data centers.

Orange County, California – Compass Energy’s large battery project in San Juan Capistrano has finally died after a yearslong bout with local opposition.

Hillsdale County, Michigan – Here’s a new one: Two county commissioners here are stepping back from any decision on a solar project because they have signed agreements with the developer.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The administration has begun shuffling projects forward as court challenges against the freeze heat up.

The Trump administration really wants you to think it’s thawing the freeze on renewable energy projects. Whether this is a genuine face turn or a play to curry favor with the courts and Congress, however, is less clear.

In the face of pressures such as surging energy demand from artificial intelligence and lobbying from prominent figures on the right, including the wife of Trump’s deputy chief of staff, the Bureau of Land Management has unlocked environmental permitting processes in recent weeks for a substantial number of renewable energy projects. Public documents, media reports, and official agency correspondence with stakeholders on the ground all show projects that had ground to a halt now lurching forward.

What has gone relatively unnoticed in all this is that the Trump administration has used this momentum to argue against a lawsuit filed by renewable energy groups challenging Trump’s permitting freeze. In January, for instance, Heatmap was first to report that the administration had lifted its ban on eagle take permits for wind projects. As we predicted at the time, after easing that restriction, Trump’s Justice Department has argued that the judge in the permitting freeze case should reject calls for an injunction. “Arguments against the so-called Eagle Permit Ban are perhaps the easiest to reject. [The Fish and Wildlife Service] has lifted the temporary pause on the issuance of Eagle take permits,” DOJ lawyers argued in a legal brief in February.

On February 26, E&E News first reported on Interior’s permitting freeze melting, citing three unnamed career agency officials who said that “at least 20 commercial-scale” solar projects would advance forward. Those projects include each of the seven segments of the Esmeralda mega-project that Heatmap was first to report was killed last fall. E&E News also reported that Jove Solar in Arizona, the Redonda and Bajada solar projects in California and three Nevada solar projects – Boulder Solar III, Dry Lake East and Libra Solar – will proceed in some fashion. Libra Solar received its final environmental approval in December but hasn’t gotten its formal right-of-way for construction.

Since then, Heatmap has learned of four other projects on the list, all in Nevada: Mosey Energy Center, Kawich Energy Center, Purple Sage Energy Center and Rock Valley Energy Center.

Things also seem to be moving on the transmission front in ways that will benefit solar. BLM posted the final environmental impact statement for upgrades to NextEra’s GridLance West transmission project in Nevada, which is expected to connect to solar facilities. And NV Energy’s Greenlink North transmission line is now scheduled to receive a final federal decision in June.

On wind, the administration silently advanced the Lucky Star transmission line in Wyoming, which we’ve covered as a bellwether for the state of the permitting process. We were first to report that BLM sent local officials in Wyoming a draft environmental review document a year ago signaling that the transmission line would be approved — then the whole thing inexplicably ground to a halt. Now things are moving forward again. In early February, BLM posted the final environmental review for Lucky Star online without any public notice or press release.

There are certainly reasons why Trump would allow renewables development to move forward at this juncture.

The president is under incredible pressure to get as much energy as possible onto the electric grid to power AI data centers without causing undue harm to consumers’ pocketbooks. According to the Wall Street Journal, the oil industry is urging him to move renewables permitting forward so Democrats come back to the table on a permitting deal.

Then there’s the MAGAverse’s sudden love affair with solar energy. Katie Miller, wife of White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller, has suddenly become a pro-solar advocate at the same time as a PR campaign funded by members of American Clean Power claims to be doing paid media partnerships with her. (Miller has denied being paid by ACP or the campaign.) Former Trump senior adviser Kellyanne Conway is now touting polls about solar’s popularity for “energy security” reasons, and Trump pollster Tony Fabrizio just dropped a First Solar-funded survey showing that roughly half of Trump voters support solar farms.

This timing is also conspicuously coincidental. One day before the E&E News story, the Justice Department was granted an extension until March 16 to file updated rebuttals in the freeze case before any oral arguments or rulings on injunctions. In other court filings submitted by the Justice Department, BLM career staff acknowledge they’ve met with people behind multiple solar projects referenced in the lawsuit since it was filed. It wouldn’t be surprising if a big set of solar projects got their permitting process unlocked right around that March 16 deadline.

Kevin Emmerich, co-founder of Western environmental group Basin & Range Watch, told me it’s important to recognize that not all of these projects are getting final approvals; some of this stuff is more piecemeal or procedural. As an advocate who wants more responsible stewardship of public lands and is opposed to lots of this, Emmerich is actually quite troubled by the way Trump is going back on the pause. That is especially true after the Supreme Court’s 2025 ruling in the Seven Counties case, which limited the scope of environmental reviews, not to mention Trump-era changes in regulation and agency leadership.

“They put a lot of scrutiny on these projects, and for a while there we didn’t think they were going to move, period,” Emmerich told me. “We’re actually a little bit bummed out about this because some of these we identified as having really big environmental impacts. We’re seeing this as a perfect storm for those of us worried about public land being taken over by energy because the weakening of NEPA is going to be good for a lot of these people, a lot of these developers.”

BLM would not tell me why this thaw is happening now. When reached for comment, the agency replied with an unsigned statement that the Interior Department “is actively reviewing permitting for large-scale onshore solar projects” through a “comprehensive” process with “consistent standards” – an allusion to the web of review criteria renewable energy developers called a de facto freeze on permits. “This comprehensive review process ensures that projects — whether on federal, state, or private lands — receive appropriate oversight whenever federal resources, permits, or consultations are involved.”

Plus more of the week’s top fights in data centers and clean energy.

1. Osage County, Kansas – A wind project years in the making is dead — finally.

2. Franklin County, Missouri – Hundreds of Franklin County residents showed up to a public meeting this week to hear about a $16 billion data center proposed in Pacific, Missouri, only for the city’s planning commission to announce that the issue had been tabled because the developer still hadn’t finalized its funding agreement.

3. Hood County, Texas – Officials in this Texas County voted for the second time this month to reject a moratorium on data centers, citing the risk of litigation.

4. Nantucket County, Massachusetts – On the bright side, one of the nation’s most beleaguered wind projects appears ready to be completed any day now.

Talking with Climate Power senior advisor Jesse Lee.

For this week's Q&A I hopped on the phone with Jesse Lee, a senior advisor at the strategic communications organization Climate Power. Last week, his team released new polling showing that while voters oppose the construction of data centers powered by fossil fuels by a 16-point margin, that flips to a 25-point margin of support when the hypothetical data centers are powered by renewable energy sources instead.

I was eager to speak with Lee because of Heatmap’s own polling on this issue, as well as President Trump’s State of the Union this week, in which he pitched Americans on his negotiations with tech companies to provide their own power for data centers. Our conversation has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

What does your research and polling show when it comes to the tension between data centers, renewable energy development, and affordability?

The huge spike in utility bills under Trump has shaken up how people perceive clean energy and data centers. But it’s gone in two separate directions. They see data centers as a cause of high utility prices, one that’s either already taken effect or is coming to town when a new data center is being built. At the same time, we’ve seen rising support for clean energy.

As we’ve seen in our own polling, nobody is coming out looking golden with the public amidst these utility bill hikes — not Republicans, not Democrats, and certainly not oil and gas executives or data center developers. But clean energy comes out positive; it’s viewed as part of the solution here. And we’ve seen that even in recent MAGA polls — Kellyanne Conway had one; Fabrizio, Lee & Associates had one; and both showed positive support for large-scale solar even among Republicans and MAGA voters. And it’s way high once it’s established that they’d be built here in America.

A year or two ago, if you went to a town hall about a new potential solar project along the highway, it was fertile ground for astroturf folks to come in and spread flies around. There wasn’t much on the other side — maybe there was some talk about local jobs, but unemployment was really low, so it didn’t feel super salient. Now there’s an energy affordability crisis; utility bills had been stable for 20 years, but suddenly they’re not. And I think if you go to the town hall and there’s one person spewing political talking points that they've been fed, and then there’s somebody who says, “Hey, man, my utility bills are out of control, and we have to do something about it,” that’s the person who’s going to win out.

The polling you’ve released shows that 52% of people oppose data center construction altogether, but that there’s more limited local awareness: Only 45% have heard about data center construction in their own communities. What’s happening here?

There’s been a fair amount of coverage of [data center construction] in the press, but it’s definitely been playing catch-up with the electric energy the story has on social media. I think many in the press are not even aware of the fiasco in Memphis over Elon Musk’s natural gas plant. But people have seen the visuals. I mean, imagine a little farmhouse that somebody bought, and there’s a giant, 5-mile-long building full of computers next to it. It’s got an almost dystopian feel to it. And then you hear that the building is using more electricity than New York City.

The big takeaway of the poll for me is that coal and natural gas are an anchor on any data center project, and reinforce the worst fears about it. What you see is that when you attach clean energy [to a data center project], it actually brings them above the majority of support. It’s not just paranoia: We are seeing the effects on utility rates and on air pollution — there was a big study just two days ago on the effects of air pollution from data centers. This is something that people in rural, urban, or suburban communities are hearing about.

Do you see a difference in your polling between natural gas-powered and coal-powered data centers? In our own research, coal is incredibly unpopular, but voters seem more positive about natural gas. I wonder if that narrows the gap.

I think if you polled them individually, you would see some distinction there. But again, things like the Elon Musk fiasco in Memphis have circulated, and people are aware of the sheer volume of power being demanded. Coal is about the dirtiest possible way you can do it. But if it’s natural gas, and it’s next door all the time just to power these computers — that’s not going to be welcome to people.

I'm sure if you disentangle it, you’d see some distinction, but I also think it might not be that much. I’ll put it this way: If you look at the default opposition to data centers coming to town, it’s not actually that different from just the coal and gas numbers. Coal and gas reinforce the default opposition. The big difference is when you have clean energy — that bumps it up a lot. But if you say, “It’s a data center, but what if it were powered by natural gas?” I don’t think that would get anybody excited or change their opinion in a positive way.

Transparency with local communities is key when it comes to questions of renewable buildout, affordability, and powering data centers. What is the message you want to leave people with about Climate Power’s research in this area?

Contrary to this dystopian vision of power, people do have control over their own destinies here. If people speak out and demand that data centers be powered by clean energy, they can get those data centers to commit to it. In the end, there’s going to be a squeeze, and something is going to have to give in terms of Trump having his foot on the back of clean energy — I think something will give.

Demand transparency in terms of what kind of pollution to expect. Demand transparency in terms of what kind of power there’s going to be, and if it’s not going to be clean energy, people are understandably going to oppose it and make their voices heard.