You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Twenty-five years ago, computers were on the verge of destroying America’s energy system.

Or, at least, that’s what lots of smart people seemed to think.

In a 1999 Forbes article, a pair of conservative lawyers, Peter Huber and Mark Mills, warned that personal computers and the internet were about to overwhelm the fragile U.S. grid.

Information technology already devoured 8% to 13% of total U.S. power demand, Huber and Mills claimed, and that share would only rise over time. “It’s now reasonable to project,” they wrote, “that half of the electric grid will be powering the digital-Internet economy within the next decade.” (Emphasis mine.)

Over the next 18 months, investment banks including JP Morgan and Credit Suisse repeated the Forbes estimate of internet-driven power demand, advising their customers to pile into utilities and other electricity-adjacent stocks. Although it was unrelated, California’s simultaneous blackout crisis deepened the sense of panic. For a moment, experts were convinced: Data centers and computers would drain the country’s energy resources.

They could not have been more wrong. In fact, Huber and Mills had drastically mismeasured the amount of electricity used by PCs and the internet. Computing ate up perhaps 3% of total U.S. electricity in 1999, not the roughly 10% they had claimed. And instead of staring down a period of explosive growth, the U.S. electric grid was in reality facing a long stagnation. Over the next two decades, America’s electricity demand did not grow rapidly — or even, really, at all. Instead, it flatlined for the first time since World War II. The 2000s and 2010s were the first decades without “load growth,” the utility industry’s jargon for rising power demand, since perhaps the discovery of electricity itself.

Now that lull is ending — and a new wave of tech-driven concerns has overtaken the electricity industry. According to its supporters and critics alike, generative artificial intelligence like ChatGPT is about to devour huge amounts of electricity, enough to threaten the grid itself. “We still don’t appreciate the energy needs of this technology,” Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, has said, arguing that the world needs a clean energy breakthrough to meet AI’s voracious energy needs. (He is investing in nuclear fusion and fission companies to meet this demand.) The Washington Post captured the zeitgeist with a recent story: America, it said, “is running out of power.”

But … is it actually? There is no question that America’s electricity demand is rising once again and that load growth, long in abeyance, has finally returned to the grid: The boom in new factories and the ongoing adoption of electric vehicles will see to that. And you shouldn’t bet against the continued growth of data centers, which have increased in size and number since the 1990s. But there is surprisingly little evidence that AI, specifically, is driving surging electricity demand. And there are big risks — for utility customers and for the planet — by treating AI-driven electricity demand as an emergency.

There is, to be clear, no shortage of predictions that AI will cause electricity demand to rise. According to a recent Reuters report, nine of the country’s 10 largest utilities are now citing the “surge” in power demand from data centers when arguing to regulators that they should build more power. Morgan Stanley projects that power use from data centers “is expected to triple globally this year,” according to the same report. The International Energy Agency more modestly — but still shockingly — suggests that electricity use from data centers, AI, and cryptocurrency could double by 2026.

These concerns have also come from environmentalists. A recent report from the Climate Action Against Disinformation Commission, a left-wing alliance of groups including Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace, warned that AI will require “massive amounts of energy and water” and called for aggressive regulation.

That report focused on the risks of an AI-addled social media public sphere, which progressives fear will be filled with climate-change-denying propaganda by AI-powered bots. But in an interview, Michael Khoo, an author of the report and a researcher at Friends of the Earth, told me that studying AI made him much more frightened about its energy use.

AI is such an power-suck that it “is causing America to run out of energy,” Khoo said. “I think that’s going to be much more disruptive than the disinformation conversation in the mid-term.” He sketched a scenario where Altman and Mark Zuckerberg can outbid ordinary households for electrons as AI proliferates across the economy. “I can see people going without power,” he said, “and there being massive social unrest.”

These predictions aren’t happening in a vacuum. At the same time that investment bankers and environmentalists have fretted over a potential electricity shortage, utilities across the South have proposed a de facto solution: a massive buildout of new natural-gas power plants.

Citing the return of load growth, utilities across the South are trying to go around normal regulatory channels and build a slew of new natural-gas-burning power plants. Across at least six states, utilities have already won — or are trying to win — permission from local governments to fast-track more than 10,000 megawatts of new gas-fired power plants so that they can meet the surge in demand.

These requests have popped up across the region, pushed by vertically integrated monopoly power companies. Georgia Power won a tentative agreement to build 1,400 new megawatts of gas capacity, Canary reported. In the Carolinas, Duke Energy has asked to build 9,000 megawatts of new gas capacity, triple what it previously requested. The Tennessee Valley Authority has plans to add 6,600 megawatts of new capacity to its grid.

This buildout is big enough to endanger the country’s climate targets. Although these utilities are also building new renewable and battery farms, and shutting down coal plants, the planned surge in carbon emissions from natural gas plants would erase the reductions from those changes, according to a Southern Environmental Law Center analysis. Duke Energy has already said that it will not meet its 2030 climate goal in order to conduct the gas expansion.

In the popular press, AI’s voracious energy demand is sometimes said to be a major driver of this planned gas boom. But evidence for that proposition is slim, and the utilities have said only that data center expansion is one of several reasons for the boom. The Southeast’s population is growing, and the region is experiencing a manufacturing renaissance, due in part to the new car, battery, and solar panel factories subsidized by Biden’s climate law. Utilities in the South also face a particular challenge coping with the coldest winter mornings because so many homes and offices use inefficient and power-hungry space heaters.

Indeed, it’s hard to talk about the drivers of load growth with any specificity — and it’s hard to know whether load growth will actually happen in all corners of the South.

Utilities compete against each other to secure big-name customers — much like local governments compete with sweetheart tax deals — so when a utility asks regulators to build more capacity, it doesn’t reveal where potential power demand is coming from. (In other words, it doesn’t reveal who it believes will eventually buy that power.) A company might float plans to build the same data center or factory in multiple states to shop around for the best rates, which means the same underlying gigawatts of demand may be appearing in several different utilities’ resource plans at the same time. In other words, utilities are unlikely to actually see all of the demand they’re now projecting.

Even if we did know exactly how many gigawatts of new demand each utility would see, it’s almost impossible to say how much of it is coming from AI. Utilities don’t say how much of their future projected power demand will come from planned factories versus data centers. Nor do they say what each data center does and whether it trains AI (or mines Bitcoin, which remains a far bigger energy suck).

The risk of focusing on AI, specifically, as a driver of load growth is that because it’s a hot new technology — one with national security implications, no less — it can rhetorically justify expensive emergency action that is actually not necessary at all. Utilities may very well need to build more power capacity in the years to come. But does that need constitute an emergency? Does it justify seeking special permission from their statehouses or regulators to build more gas, instead of going through the regular planning process? Is it worth accelerating approvals for new gas plants? Probably not. The real danger, in other words, is not that we’ll run out of power. It’s that we’ll build too much of the wrong kind.

At the same time, we might have been led astray by overly dire predictions of AI’s energy use. Jonathan Koomey, a researcher who studies how the internet and data centers use energy (and the namesake of Koomey’s Law) told me that many estimates of Nvidia’s most important AI chips assume that their energy use is the same as their advertised “rated” power. In reality, Nvidia chips probably use half of that amount, he said, because chipmakers engineer their chips to withstand more electricity than is necessary for safety reasons.

And this is just the current generation of chips: Nvidia’s next generation of AI-training chips, called “Blackwell,” use 25 times less energy to do the same amount of computation as the previous generation of chips.

Koomey helped defuse the last panic over energy use by showing that the estimates Huber and Mills relied on were wildly incorrect. Estimates now suggest that the internet used less than 1% of total U.S. electricity by the late 1990s, not 13% as they claimed. Those percentages stayed roughly the same through 2008, he later found, even as data centers grew and computers proliferated across the economy. That’s the same year, remember, that Huber and Mills predicted that the internet would consume half of American energy.

These bad predictions were extremely convenient. Mills was a scientific advisor to the Greening Earth Society, a fossil-fuel-industry-funded group that alleged carbon dioxide pollution would actually improve the global environment. He aimed to show that climate and environmental policy would conflict with the continued growth of the internet.

“Many electricity policy proposals are on a collision course with demand forces,” Mills said in a Greening Earth press release at the time. “While many environmentalists want to substantially reduce coal use in making electricity, there is no chance of meeting future economically-driven and Internet-accelerated electric demand without retaining and expanding the coal component.” Hence the headline of the Forbes piece: “The PCs are coming — Dig more coal.”

What makes today’s AI-induced fear frenzy different from 1999 is that the alarmed projections are not just coming from businesses and banks like Morgan Stanley, but from environmentalists like Friends of the Earth. Yet neither their estimates of near-term, AI-driven power shortages — nor the analysis from Morgan Stanley that U.S. data-center use could soon triple within a year — make sense given what we know about data centers, Koomey said. It is not logistically possible to triple data centers’ electricity use in one year. “There just aren’t enough people to build data centers, and it takes longer than a year to build a new data center anyway,” he said. “There aren’t enough generators, there aren’t enough transformers — the backlog for some equipment is 24 months. It’s a supply chain constraint.”

Look around and you might notice that we have many more servers and computers today than we did in 1999 — not to mention smartphones and tablets, which didn’t even exist then — and yet computing doesn’t devour half of American energy. It doesn’t even get close. Today, computers use 1% to 4% of total U.S. power demand, depending on which estimate you trust. That’s about the same share of total U.S. electricity demand that they used in the late 1990s and mid-2000s.

It may well be that AI devours more energy in years to come, but utilities probably do not need to deal with it by building more gas. They could install more batteries, build new power lines, or even pay some customers to reduce their electricity usage during certain peak events, such as cold winter storms.

There are some places where AI-driven energy demand could be a problem — Koomey cited Ireland and Loudon County, Virginia, as two epicenters. But even there, building more natural gas is not the sole way to cope with load growth.

“The problem with this debate is everybody is kind of right,” Daniel Tait, who researches Southern utilities for the Energy and Policy Institute, a consumer watchdog, told me. “Yes, AI will increase load a little bit, but probably not as much as you think. Yes, load is growing, but maybe not as much as you say. Yes, we do need to build stuff, but maybe not the stuff that you want.”

There are real risks if AI’s energy demands get overstated and utilities go on a gas-driven bender. The first is for the planet: Utilities might overbuild gas plants now, run them even though they’re non-economic, and blow through their climate goals.

“Utilities — especially the vertically integrated monopoles in the South — have every incentive to overstate load growth, and they have a pattern of having done that consistently,” Gudrun Thompson, a senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, told me. In 2017, the Rocky Mountain Institute, an energy think tank, found in 2017 that utilities systematically overestimated their peak demand when compiling forecasts. This makes sense: Utilities would rather build too much capacity than wind up with too little, especially when they can pass along the associated costs to rate-payers.

But the second risk is that utilities could burn through the public’s willingness to pay for grid upgrades. Over the next few years, utilities should make dozens of updates to their systems. They have to build new renewables, new batteries, and new clean 24/7 power, such as nuclear or geothermal. They will have to link their grids to their neighbors’ by building new transmission lines. All of that will be expensive, and it could require the kind of investment that raises electricity rates. But the public and politicians can accept only so many rate hikes before they rebel, and there’s a risk that utilities spend through that fuzzy budget on unnecessary and wasteful projects now, not on the projects that they’ll need in the future.

There is no question that AI will use more electricity in the years to come. But so will EVs, new factories, and other sources of demand. America is on track to use more electricity. If that becomes a crisis, it will be one of our own making.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Topsy turvy oil prices aren’t great for the U.S.

Oil prices are all over the place as markets reopened this week, climbing as high as $120 a barrel before crashing to around $85 after Donald Trump told CBS News that the war with Iran “is very complete, pretty much,” and that he was “thinking about taking it over,” referring to the Strait of Hormuz, the artery through which about a third of the world’s traded oil flows.

Even $85 is substantially higher than the $57 per barrel price from the end of last year. At that point, forecasters from both the public and the private sectors were expecting oil to stick around $60 a barrel through 2026.

Of course, crude oil itself is not something any consumer buys — but those high prices would likely feed through to higher consumer prices throughout the U.S. economy. That includes the price of gasoline, of course, which has risen by about $0.50 a gallon in the past month, according to AAA, — and jet fuel, which will mean increased travel costs. “Book your airfares now if they haven’t moved already,” Skanda Amarnath, the executive director of the economic policy think tank Employ America, told me.

High oil prices also raise the price of goods and services not directly linked to oil prices — groceries, for instance. “The cost of food, especially at the grocery store, is a function of the cost of diesel,” which fuels the trucks that get food to shelves, Amarnath told me. Diesel prices have risen even more than gasoline in the past week, by over $0.85 a gallon.

“We’ll see how long these prices stay elevated, how they feed their way through the supply chain and the value chain. But it’s clearly the case that it is a pretty adverse situation for both businesses and consumers.”

The oil market is going through one of the largest physical shocks in its modern history. Bloomberg’s Javier Blas estimates that of the 15 million barrels per day that regularly flow through the Strait of Hormuz, only about a third is getting through to the global market, whether through the strait itself or by alternative routes, such as the pipeline from Saudi Arabia’s eastern oil fields to the Red Sea.

Global daily oil production is just above 100 million barrels per day, meaning that around 10% of the oil supply on the market is stuck behind an effective blockade.

“The world is suddenly ‘short’ a volume that, in normal times, would dwarf almost any supply/demand imbalance we debate,” Morgan Stanley oil analyst Martjin Rats wrote in a note to clients on Sunday.

The fact that the U.S. is itself a leading producer and exporter of oil will only provide so much relief. Private sector economists have estimated that every $10 increase in the price of oil reduces economic growth somewhere between 0.1 and 0.2 percentage points.

“Petroleum product prices here in the U.S. tend to reflect global market conditions, so the price at the pump for gasoline and diesel reflect what’s going on with global prices,” Ben Cahill, a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told me. “What happens in the rest of the world still has a deep impact on U.S. energy prices.”

To the extent the U.S. economy benefits from its export capacity, the effects are likely localized to areas where oil production and export takes place, such as Texas and Louisiana. For the economy as a whole, higher oil prices will improve the “terms of trade,” essentially a measure of the value of imports a certain quantity of exports can “buy,” Ryan Cummings, chief of staff at Stanford Institute for Economic Policymaking, told me.

Could the U.S. oil industry ramp up production to capture those high prices and induce some relief?

Oil industry analysts, Heatmap founding executive editor Robinson Meyer, and the TV show Landman have all theorized that there is a “goldilocks” range of oil prices that are high enough to encourage exploration and production but not so high as to take out the economy as a whole. This range starts at around $60 or $70 on the low end and tops out at around $90 or $95. Above that, the economic damage from high prices would likely outweigh any benefit to drillers from expanded production.

And that’s if production were to expand at all.

“Capital discipline” has been the watchword of the U.S. oil and gas industry for years since the shale boom, meaning drillers are unlikely to chase price spikes by ramping up production heedlessly, CSIS’ Ben Cahill told me. “I think they’ll be quite cautious about doing that,” he said.

A test drive provided tantalizing evidence that a great, cheap EV is possible for the U.S.

Midway through the tortuous test drive over the mountains to Malibu, as the new Chevrolet Bolt EV ably zipped through a series of sharp canyon corners, I couldn’t help but think: Who would want to kill this car?

Such is life for the Bolt. Chevy revived the budget electric car after its fans howled when it killed the first version in 2023. But by the time the car press assembled last week for the official test drive of Bolt 2.0, the new car already had an expiration date: General Motors said it would end the production run next summer. This is a shame for a variety of reasons. Among the most important: The new Bolt, which starts just under $30,000 and is soon to start arriving at Chevy dealerships, shows that the cheap EV for the masses is really, almost there.

The 2027 Bolt comes with a 65 kilowatt-hour lithium iron phosphate battery that’s rated to deliver 262 miles of range. That’s not bad for an economy car, given that lots of more expensive EVs came with ranges in the low 200s just a couple of years ago.

Charging speed, the big bugaboo with the original Bolt, is fixed. The glacial 50-kilowatt speed has risen to 150 kilowatts, allowing the car to charge from 10% to 80% in about 25 minutes. That pales in comparison to the 350-kilowatt Hyundai touts for some of its EVs, but it makes the Bolt road trip an acceptable experience, not a slog. Crucially, the new Bolt comes with the NACS port and will seamlessly plug-and-charge at many charging stations, including Tesla’s.

Bolt comes with a single motor that delivers 210 horsepower and 169 pound-feet of torque — not eye-popping numbers. But because all of an electric car’s torque is available at any time, the Bolt feels livelier as it accelerates away from a start compared to an equivalent combustion-powered economy car. It huffs and puffs just a tad trying to accelerate uphill on California’s mountain highways, sure, but Bolt has enough oomph to have some fun without getting you into trouble. And in a world of white cars, Bolt comes in honest-to-goodness colors. Red. Blue. Yellow!

The tech features are the same story — that is, plenty good for the price. Many Bolt loyalists are incensed that Chevy killed off Apple Carplay and Android Auto integration in the new car, forcing drivers to rely on what’s built in. For those who can get over the disappointment, what is built into Bolt’s 11-inch touchscreen is pretty good, starting with Google Maps integration for navigation. Its method for displaying charging stations — and allowing the driver to filter them by plug style, provider, and other factors — isn’t quite up to the Silicon Valley seamlessness of a Rivian, but is easier to use than what a lot of legacy car companies put in their EVs. (The fabulous Kia EV9 three-row SUV I tested just before the Bolt is superior in just about every way except this.)

The Bolt even has a few features you wouldn’t expect at the entry level. The surround vision recorder for storing footage from the car’s camera is a first for a GM vehicle, Chevy says. The brand is also making a big to-do over the Super Cruise hands-free driving feature since the Bolt is now the least expensive car to get it, though adding all that tech takes the basic LT version of the Bolt up from $29,000 to more than $35,000, which is the starting price for the bigger Chevy Equinox EV.

With so much going right for this vehicle, why preemptively kill it? The most obvious factor is the Trump White House. Chevrolet had always called the Bolt’s return a limited run, but the fact that its production run might last for just a year and a half is a direct result of Trump tariffs: GM wants to make gas-powered Buick crossovers, currently made in China, at the Kansas factory that builds the Bolt.

And the loss last year of the federal incentive to buy an EV is particularly punitive for the Bolt. With $7,500 shaved off the price, the Chevy EV would have been cost-competitive with the cheapest new gas cars, like the Hyundai Elantra or Toyota Corolla. Without it, Bolt is closer in price to a larger vehicle like the Toyota RAV4. When Chevy can’t make the case that its EV is as cheap as any other small car you might be looking at, it must sell a car like Bolt on its down-the-road value: very little routine maintenance, no buying gasoline during a period of wartime oil shocks, and so on. That’s a tougher task, and perhaps explains why GM was so quick to move on.

Still, there’s clearly something bigger at stake here for GM. The American car companies’ pivot back to the short-term profitability of petroleum, exemplified by the Bolt-Buick affair, comes as the rest of the world continues to embrace EVs. Headlines lately have wondered whether China’s ascent combined with America’s yoyo-ing on electric power could lead to Detroit’s outright demise, leaving the U.S. auto industry with scraps as someone else’s superior EVs take over the world.

In this light, Chevy’s own market data on Bolt is especially jarring. Of the nearly 200,000 Bolts on the road from the car’s previous generation, 75% percent of those drivers came from other car companies to GM, and 72% remained loyal to GM. In other words, the new Bolt is set to build on General Motors’ status as the top EV-seller in America behind Tesla by expanding the established base of customers who love Chevy electric cars. That is what’s being tossed aside to increase quarterly profits.

Maybe the Bolt will surprise its maker, again. Even if a groundswell of enthusiasm for the new car isn’t enough to save it from extinction, perhaps it will prove to GM to give the budget EV yet another go-around when the market shifts yet again.

Current conditions: Spring-like temperatures have arrived in New York City, with a high of 62 degrees Fahrenheit today • The death toll from the flooding in Nairobi, Kenya, has risen to at least 42 • Heavy rain in Peru threatens landslides amid what’s already been a deadly wet season.

It only took a week. But, as I told you might happen sooner than later, oil prices surged past $100 per barrel for the first time since 2022 as the war against Iran continues. The latest hit to the global market came when Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates started cutting production over the weekend at key oil fields as shipments through the Strait of Hormuz ground to a halt. In a post on his Truth Social network, President Donald Trump said prices “will drop rapidly when the destruction of the Iran nuclear threat is over,” calling the rise “a very small price to pay for U.S.A.” In response, oil analyst Rory Johnston said Trump’s statement would only spur on the market craziness. “No one who has any idea how the oil market works is buying it — all this does is make it seem like Trump believes it, which means the base case length of this disruption is growing ever-longer,” he wrote. “Tick. Tock.”

The war’s effect on energy markets isn’t just an oil story. As Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote, it’s also a natural gas story. Similarly, as Matthew wrote last week, the winners of the market chaos run the gamut from coal to solar panels.

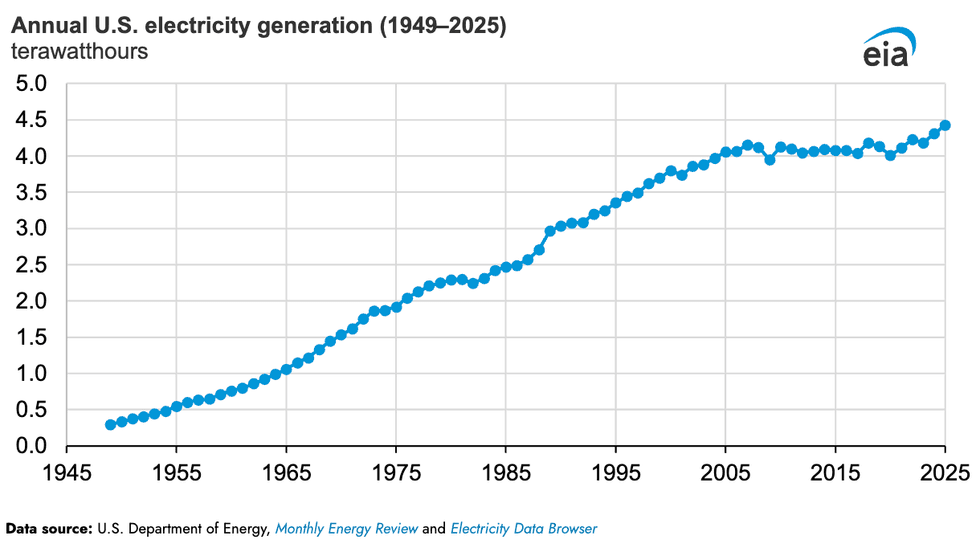

The numbers are in. Last year, the United States generated 4,430 terawatt-hours of electricity. That’s up 2.8% from 2024, which previously had been the highest annual total in the Energy Information Administration’s record books, which date back to 1949. Residential electricity sales grew 2.2%, while commercial surged by 2.9% and industrial rose by just 0.7%.

France produced a record 521.1 terawatt-hours of low-carbon electricity in 2025 as upgrades to existing nuclear reactors allowed the fleet to produce more power, according to data from the grid operator RTE. The latest report is not yet public on RTE’s website, but NucNet reviewed the findings. The electricity mix has largely remained steady for the last two years. France first achieved a 95% low-carbon grid back in 2024, RTE data shows.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Qcells has resumed solar panel assembly at its plant in Cartersville, Georgia, following a series of delays. By the end of this year, the South Korean-owned company said it plans to add the capacity to pump out 3.3 gigawatts of ingots, wafers, and cells per year. “We are proud to be back to work manufacturing the American-made energy the country needs right now,” Marta Stoepker, head of communications at Qcells, said in a statement. “Like any company, hurdles have and will occur, which requires us to adapt and be nimble, but our overall goal remains the same — to build a complete American solar supply chain.” The moves comes as MAGA warms to solar power as part of a broader “renewables thaw” that Heatmap’s Jael Holzman reported is part of a legal strategy.

Roughly two hours away, SK Battery America laid off nearly 1,000 workers at its factory northeast of Atlanta as automakers cool on electric vehicles. Friday marked the last working day for 958 employees, according to a federal filing the Associated Press reviewed.

A wave energy startup hoping to harness one of the trickier sources of renewable power just broke a record with its latest pilot project. Last month, Eco Wave Power deployed its EWP-EDF One technology Jaffa Port in Israel. The pilot test lasted nine days last month under moderate conditions with daily average wave heights between one and two meters. Throughout the test, the project generated about 2,000 kilowatthours of electricity. “Not only did we continue stable production during moderate wave conditions, but we also experienced the highest waves recorded at our site to date,” Inna Braverman, Eco Wave Power’s chief executive, said in a statement to the trade publication Offshore Energy. “Achieving record average and peak power production during 3-meter wave events provides meaningful validation of our technology’s performance potential as we scale toward commercial projects.”

Scientists discovered a molecular trick used by a unique group of plants to convert sunlight into food. Hornworts are the only known land plant that possesses internal compartments that concentrate carbon dioxide similarly to algae. A new study by researchers at the Boyce Thompson Institute, Cornell University, and the University of Edinburgh suggests that genes from the plants could be used to breed more resistant crops such as wheat. “This research shows that nature has already tested solutions we can learn from,” said Fay-Wei Li, a co-author of the study, said in a statement. “Our job is to understand those solutions well enough to apply them where they're needed most — in the crops that feed the world.”

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to correct the added manufacturing capacity at Qcells’ Cartersville plant.