You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Or maybe you want to go electric? Because yes, they are different.

Have you given much thought to the inner workings of your stove? Me neither. Your home probably came with one already installed, and so long as you can turn it on, boil some water and simmer up a sauce, perhaps that’s reason enough not to second guess it.

But if you’re cooking with gas, we’re here to let you know that, culinary connoisseur or not, there are undeniable benefits to switching to either electric or induction cooking. First and foremost, neither relies directly on fossil fuels or emits harmful pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide into your home, making the switch integral to any effort to decarbonize your life — not to mention establish a comfortable living environment. Second, both electric and induction are far more energy efficient than gas.

“So on a gas range, about 70% of the heat that is generated from the gas goes into your kitchen,” DR Richardson, co-founder of the home electrification platform Elephant Energy, told me. “So it's very inefficient. You get hot. The handle gets hot. The kitchen gets hot. Everything gets hot, except your food. And it takes a really long time.” With an electric or induction stove, you can boil water faster and heat your food up quicker, all while reducing your home’s carbon footprint.

Convinced yet? If you’re reading this guide, we sure hope you’re at least intrigued! But even after you’ve decided to make the switch, confusion and analysis paralysis can still loom. Are your needs better suited to electric or induction? Will expensive electrical upgrades be required? How will this impact your cooking? And where are all the stove stores, anyway? So before you start browsing the aisles and showrooms, let’s get up to speed on all things stoves… or is it ranges? You’ll see.

Friday Apaliski is the director of communications at the Building Decarbonization Coalition, a nonprofit composed of members across various sectors including environmental justice groups, energy providers, and equipment manufacturers, seeking alignment on a path towards the elimination of fossil fuels in buildings.

DR Richardson is a co-founder of Elephant Energy, a platform that aims to simplify residential electrification for both homeowners and contractors. The company provides personalized electrification roadmaps and handles the entire installation process, including helping homeowners take advantage of all the available local, state, and federal incentives.

It depends on the cookware you currently own, but you will almost certainly need to replace some items. Induction stoves work with pots and pans that are made of magnetic materials like cast iron and stainless steel, but not those made of glass, aluminum, or copper. You can check to see if your cookware is induction compatible by seeing if a magnet will stick to the bottom, or if the induction logo is present on the bottom.

Everyone has their own affinities, but what we can tell you is that both traditional electric stoves and newer induction stoves are more energy efficient than gas stoves, and when it comes to temperature control, induction stoves are the clear winner. They allow you to make near instantaneous heat adjustments with great precision, while gas stoves take longer to adjust and are less exact to begin with.

Cooking on a new stove will undoubtedly come with a learning curve, what with all the new knobs and buttons and little sounds to get used to. Many cooks are used to relying on the visual cue of the flame to let them know how hot the stove is, but now you’ll be relying on a number on the screen, instead. Especially if you go with induction stove, be assured that you’ll be in good company among some top chefs.

This is indeed a key question — more on this one below.

If you don’t know already, it’s not too hard to find out. When you turn on the stovetop, is there fire? That, folks, is a gas stovetop. It will have a gas supply line that looks like a threaded pipe that connects to the back of the appliance. Gas stovetops are tricky to clean, not particularly sleek, and most prevalent in California, New Jersey, Illinois, Washington DC, New York, and Nevada.

If you have an electric range, the stovetop will be flat with metal coils either exposed or concealed beneath a ceramic glass surface. The coils will glow bright when they’re on. Electric ranges plug directly into 240-volt outlets (newer versions have four prongs, older ones have three), with a cord that looks like a heavy vacuum plug or a small hose. Electric stovetops are always paired with electric ovens — this is the setup that the majority of Americans already have according to the Energy Information Administration.

“So if you have an electric range and you like it, that's wonderful. You should keep it. But generally, when we're talking about transitioning from a gas experience to something else, induction is a much more analogous cooking experience,” Apaliski said.

If you have an induction range, it was probably a very intentional choice! According to a 2022 Consumer Reports survey, only about 3% of Americans have an induction range or cooktop, so big ups if you’re a part of that energy efficient minority. But if you just wandered into a new home and are wondering if it’s got the goods, you might have to turn on the stove to tell. Unlike an electric stovetop, you won’t see the cooking area glow because the surface isn’t actually getting hot, only the cookware is. Induction stoves also plug directly into 240-volt outlets.

But wait! There’s a chance you’re cooking with both gas and electric on a dual-fuel range. The telltale sign will be if your range connects to both a gas supply line as well as a 240-volt outlet (remember that plug?). But if it’s difficult to determine what’s going on back there, here’s what else to look out for: A metal device at the bottom and/or top of the oven’s interior that glows bright when the oven is on indicates that it’s electric! Sometimes these heating elements will be concealed, though. In that case, look for telltale signs of gas: An open flame when the oven is on or a visible pilot light when off. Newer gas stoves might not have either, but rather use an electronic ignition system that you can hear fire up about 30-45 seconds after turning on the oven. If you’re still confused, there’s always your user manual! (You kept that, right?)

If you’re going from an all-gas range to electric or induction and your stove is located on a kitchen island, for example, this could make installing the necessary electrical wiring more complex. It’s something to ask potential contractors about when you get to that stage.

Whenever you add a new electric appliance to your home, there’s the possibility that you’ll need to upgrade your electric panel to accommodate the new load. A new panel can cost thousands of dollars, though, so you’ll want to know ahead of time if this might be necessary. First, check the size of your current electric panel. You can find this information on your main breaker or fuse, a label on the panel itself, or your electric meter.

According to Rewiring America, if your panel is less than 100 amps, an upgrade could be necessary. If it’s anywhere from 100 to 150 amps, you can likely electrify everything in your home — including your range — without a panel upgrade, although some creative planning might be needed (more on that here and below, in the section on finding contractors and installers). If your panel is greater than 150 amps, it’s very likely that you can get an electric range (as well as a bevy of other electrical appliances) without upgrading.

As of now, federal incentives for electric and induction ranges, cooktops, and ovens are not yet available. But Home Electrification and Appliance Rebates programs, established via the Inflation Reduction Act, will roll out on a state-by-state basis over the course of this year and next, with most programs expected to come online in 2025. These rebates could give low- and moderate-income houses up to $840 back on the cost of switching from gas to electric or induction cooking.

While many details have yet to be released, it’s important to note that qualifying customers won’t be required to pay the full price and then apply for reimbursement — rather, the discount will be applied upfront. Once the program becomes available, your state will have a website with more information on how to apply. If you’re cash-strapped today, it could be worth waiting until the federal incentives roll out, as rebates will not be retroactively available.

Many states and municipalities already have their own incentives for electric appliance upgrades though. Unfortunately, there’s currently no centralized database to look these up, so that means doing a little homework. Check with your local utility, as well as your local and state government websites and energy offices for home electrification incentives. If you happen to live in California or Washington state, you can search for local incentives here, via this initiative from the Building Decarbonization Coalition. The NODE Collective is also working to compile data on all residential incentive programs, so keep checking in, more information is coming soon!

Assuming you currently have a gas stove or a dual fuel range, this is the first big choice you’ll have to make. For customers interested in upgrading from electric to induction, let this also be your guide, as an induction stove is indeed the higher-end choice. Here are the main differences between the two:

Electric

Induction

*According to Rewiring America

** According to this paper

Heatmap Recommends: Spring for the induction stove if you can. Not only will it provide a superior cooking experience, but it’s safer too. Induction stoves only heat up magnetic pots and pans, so if you touch the stove’s surface, you won’t get burned. Most will also turn off automatically if there’s no cookware detected.

“Induction is definitely the upgrade in basically every sense, if you can afford it. Induction is a way better cooking experience. It's got way more fun heating and cooking control. It's much more energy efficient. It's much faster,” said Richardson.

If you’re curious about what it’s like to cook with an electric or induction stove, you can buy a standalone single-pot cooktop for well under $100; it will plug straight into a standard outlet. Additionally, Apalinksi says that many libraries (yes, libraries!) and utilities allow residents to borrow an induction cooktop and try it out for a few weeks, completely free of charge.

New electric and induction ranges and cooktops will only be eligible for forthcoming federal incentives if they’re certified by Energy Star, a joint program run by the Environmental Protection Agency and the DOE that provides consumer information on energy efficient products, practices, and standards. You can check out what models of ranges and cooktops qualify here. But to get a handle on the actual look and feel of various options, you should try and find a showroom or head to a large retail store.

“Go to your local big box retailer, whether it's a Home Depot or Best Buy or Lowe's, they tend to have a bunch of models on the floor. Their representatives can talk to you about all the different options out there. But you have to research a little bit ahead of time, otherwise they're going to point you to the latest gas appliance,” said Richardson.

If you learn that making the switch is going to entail particularly cumbersome electrical upgrades, Apaliski said there are some innovative companies such as Channing Street Copper and Impulse Labs that make induction ranges and cooktops that plug into standard outlets. They’re much pricier than your standard range, but if you can afford it, one could be right if you’re looking for plug-and-play simplicity and sleek design.

“So this is great, for example, if you are a renter, or if you are someone who has limited capacity on your electrical panel, or if you are someone who has one of these kitchen islands that is just impossible to get a new electric cord to,” Apaliski said.

If you buy your new range or cooktop from a big box retailer, they’ll typically haul away your old appliance and deliver and install the new one for you at either low or no cost. Don’t assume this is a part of the package, though, and be sure to ask what is and isn’t included before you make your purchase.

But if you’re moving from an all gas range or cooktop to an electric or induction range or cooktop, the complicated part isn’t the installation process, it’s everything that must come before. That includes capping and sealing the gas line for your old stove (this is a job for a plumber) and installing the requisite electric wiring to power your new stove (this is a job for an electrician).

As noted, making the switch could also mean a costly electric panel upgrade. You should ask potential electricians about this right away, as well as about creative solutions that would let you work with your existing panel. If you’re running out of space, you could buy a circuit sharing device like a smart splitter or a circuit pauser, which would allow multiple loads, such as an EV charger and your stove, to share a circuit, or ensure that specific appliances are shut off when you’re approaching your panel’s limit. Richardson recommends getting opinions from a couple different electricians, seconding the idea that if your panel is 100 amps or more, an upgrade is likely not necessary.

Above all, you should make sure that the gas line and electric work is taken care of before the stove installer comes to your home. Richardson said that occasionally, retailers will provide plumbing and electrical services as an add-on option, so it never hurts to ask. But most likely you’ll be sourcing contractors and compiling quotes on your own. If you don’t already have a go to person for the job, ask friends, family, and neighbors for references. Google and Yelp reviews are always there too.

New electric ranges do not usually come with a power cord. You must purchase your own power cord prior to installation.

Once you get time on the calendar with a trustworthy, knowledgeable and fair-priced plumber and electrician, it’s time to schedule the installation of your new range or cooktop. And after that it’s time to metaphorically fire up those resistive coils or electromagnetic fields and make yourself an electrified meal for the ages.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The startup — founded by the former head of Tesla Energy — is trying to solve a fundamental coordination problem on the grid.

The concept of virtual power plants has been kicking around for decades. Coordinating a network of distributed energy resources — think solar panels, batteries, and smart appliances — to operate like a single power plant upends our notion of what grid-scale electricity generation can look like, not to mention the role individual consumers can play. But the idea only began taking slow, stuttering steps from theory to practice once homeowners started pairing rooftop solar with home batteries in the past decade.

Now, enthusiasm is accelerating as extreme weather, electricity load growth, and increased renewables penetration are straining the grid and interconnection queue. And the money is starting to pour in. Today, home battery manufacturer and VPP software company Lunar Energy announced $232 million in new funding — a $102 million Series D round, plus a previously unannounced $130 million Series C — to help deploy its integrated hardware and software systems across the U.S.

The company’s CEO, Kunal Girotra, founded Lunar Energy in the summer of 2020 after leaving his job as head of Tesla Energy, which makes the Tesla Powerwall battery for homeowners and the Megapack for grid-scale storage. As he put it, back then, “everybody was focused on either building the next best electric car or solving problems for the grid at a centralized level.” But he was more interested in what was happening with households as home battery costs were declining. “The vision was, how can we get every home a battery system and with smart software, optimize that for dual benefit for the consumer as well as the grid?”

VPPs work by linking together lots of small energy resources. Most commonly, this includes solar, home batteries, and appliances that can be programmed to adjust their energy usage based on grid conditions. These disparate resources work in concert conducted by software that coordinates when they should charge, discharge, or ramp down their electricity use based on grid needs and electricity prices. So if a network of home batteries all dispatched energy to the grid at once, that would have the same effect as firing up a fossil fuel power plant — just much cleaner.

Lunar’s artificial intelligence-enabled home energy system analyzes customers’ energy use patterns alongside grid and weather conditions. That allows Lunar’s battery to automatically charge and discharge at the most cost-effective times while retaining an adequate supply of backup power. The batteries, which started shipping in California last year, also come integrated with the company’s Gridshare software. Used by energy companies and utilities, Gridshare already manages all of Sunrun’s VPPs, including nearly 130,000 home batteries — most from non-Lunar manufacturers — that can dispatch energy when the grid needs it most.

This accords with Lunar’s broader philosophy, Girotra explained — that its batteries should be interoperable with all grid software, and its Gridshare platform interoperable with all batteries, whether they’re made by Lunar or not. “That’s another differentiator from Tesla or Enphase, who are creating these walled gardens,” he told me. “We believe an Android-like software strategy is necessary for the grid to really prosper.” That should make it easier for utilities to support VPPs in an environment where there are more and more differentiated home batteries and software systems out there.

And yet the real-world impact of VPPs remains limited today. That’s partially due to the main problem Lunar is trying to solve — the technical complexity of coordinating thousands of household-level systems. But there are also regulatory barriers and entrenched utility business models to contend with, since the grid simply wasn’t set up for households to be energy providers as well as consumers.

Girotra is well-versed in the difficulties of this space. When he first started at Tesla a decade ago, he helped kick off what’s widely considered to be the country’s first VPP with Green Mountain Power in Vermont. The forward-looking utility was keen to provide customers with utility-owned Tesla Powerwalls, networking them together to lower peak system demand. But larger VPPs that utilize customer-owned assets and seek to sell energy from residential batteries into wholesale electricity markets — as Lunar wants to do — are a different beast entirely.

Girotra thinks their time has come. “This year and the next five years are going to be big for VPPs,” he told me. The tide started to turn in California last summer, he said, after a successful test of the state’s VPP capacity had over 100,000 residential batteries dispatching more than 500 megawatts of power to the grid for two hours — enough to power about half of San Francisco. This led to a significant reduction in electricity demand during the state’s evening peak, with the VPP behaving just like a traditional power plant.

Armed with this demonstration of potential and its recent influx of cash, Lunar aims to scale its battery fleet, growing from about 2,000 deployed systems today to about 10,000 by year’s end, and “at least doubling” every year after that. Ultimately, the company aims to leverage the popularity of its Gridshare platform to become a market maker, helping to shape the structure of VPP programs — as it’s already doing with the Community Choice Aggregators that it’s partnered with so far in California.

In the meantime, Girotra said Lunar is also involved in lobbying efforts to push state governments and utilities to make it easier for VPPs to participate in the market. “VPPs were always like nuclear fusion, always for the future,” he told me. But especially after last year’s demonstration, he thinks the entire grid ecosystem, from system operators to regulators, are starting to realize that the technology is here today. ”This is not small potatoes anymore.”

If all the snow and ice over the past week has you fed up, you might consider moving to San Francisco, Los Angeles, Phoenix, Austin, or Atlanta. These five cities receive little to no measurable snow in a given year; subtropical Atlanta technically gets the most — maybe a couple of inches per winter, though often none. Even this weekend’s bomb cyclone, which dumped 7 inches across parts of northeastern Georgia, left the Atlanta suburbs with too little accumulation even to make a snowman.

San Francisco and the aforementioned Sun Belt cities are also the five pilot locations of the all-electric autonomous-vehicle company Waymo. That’s no coincidence. “There is no commercial [automated driving] service operating in winter conditions or freezing rain,” Steven Waslander, a University of Toronto robotics professor who leads WinTOR, a research program aimed at extending the seasonality of self-driving cars, told me. “We don’t have it completely solved.”

Snow and freezing rain, in particular, are among the most hazardous driving conditions, and 70% of the U.S. population lives in areas that experience such conditions in winter. But for the same reasons snow and ice are difficult for human drivers — reduced visibility, poor traction, and a greater need to react quickly and instinctively in anticipation of something like black ice or a fishtailing vehicle in an adjacent lane — they’re difficult for machines to manage, too.

The technology that enables self-driving cars to “see” the road and anticipate hazards ahead comes in three varieties. Tesla Autopilot uses cameras, which Tesla CEO Elon Musk has lauded for operating naturally, like a human driver’s eye — but they have the same limitations as a human eye when conditions deteriorate, too.

Lidar, used by Waymo and, soon, Rivian, deploys pulses of light that bounce off objects and return to sensors to create 3D images of the surrounding environment. Lidar struggles in snowy conditions because the sensors also absorb airborne particles, including moisture and flakes. (Not to mention, lidar is up to 32 times more expensive than Tesla’s comparatively simple, inexpensive cameras.) Radar, the third option, isn’t affected by darkness, snow, fog, or rain, using long radio wavelengths that essentially bend around water droplets in the air. But it also has the worst resolution of the bunch — it’s good at detecting cars, but not smaller objects, such as blown tire debris — and typically needs to be used alongside another sensor, like lidar, as it is on Waymo cars.

Driving in the snow is still “definitely out of the domain of the current robotaxis from Waymo or Baidu, and the long-haul trucks are not testing those conditions yet at all,” Waslander said. “But our research has shown that a lot of the winter conditions are reasonably manageable.”

To boot, Waymo is now testing its vehicles in Tokyo and London, with Denver, Colorado, set to become the first true “winter city” for the company. Waymo also has ambitions to expand into New York City, which received nearly 12 inches of snow last week during Winter Storm Fern.

But while scientists are still divided on whether climate change is increasing instances of polar vortices — which push extremely cold Arctic air down into the warmer, moister air over the U.S., resulting in heavy snowfall — we do know that as the planet warms, places that used to freeze solid all winter will go through freeze-thaw-refreeze cycles that make driving more dangerous. Freezing rain, which requires both warm and cold air to form, could also increase in frequency. Variability also means that autonomous vehicles will need to navigate these conditions even in presumed-mild climates such as Georgia.

Snow and ice throw a couple of wrenches at autonomous vehicles. Cars need to be taught how to brake or slow down on slush, soft snow, packed snow, melting snow, ice — every variation of winter road condition. Other drivers and pedestrians also behave differently in snow than in clear weather, which machine learning models must incorporate. The car itself will also behave differently, with traction changing at critical moments, such as when approaching an intersection or crosswalk.

Expanding the datasets (or “experience”) of autonomous vehicles will help solve the problem on the technological side. But reduced sensor accuracy remains a big concern — because you can only react to hazards you can identify in the first place. A crust of ice over a camera or lidar sensor can prevent the equipment from working properly, which is a scary thought when no one’s in the driver’s seat.

As Waslander alluded to, there are a few obvious coping mechanisms for robotaxi and autonomous vehicle makers: You can defrost, thaw, wipe, or apply a coating to a sensor to keep it clear. Or you can choose something altogether different.

Recently, a fourth kind of sensor has entered the market. At CES in January, the company Teradar demonstrated its Summit sensor, which operates in the terahertz band of the electromagnetic spectrum, a “Goldilocks” zone between the visible light used by cameras and the human eye and radar. “We have all the advantages of radar combined with all the advantages of lidar or camera,” Gunnar Juergens, the SVP of product at Teradar, told me. “It means we get into very high resolution, and we have a very high robustness against any weather influence.”

The company, which raised $150 million in a Series B funding round last year, says it is in talks with top U.S. and European automakers, with the goal of making it onto a 2028 model vehicle; Juergens also told me the company imagines possible applications in the defense, agriculture, and health-care spaces. Waslander hadn’t heard of Teradar before I told him about it, but called the technology a “super neat idea” that could prove to be a “really useful sensor” if it is indeed able to capture the advantages of both radar and lidar. “You could imagine replacing both with one unit,” he said.

Still, radar and lidar are well-established technologies with decades of development behind them, and “there’s a reason” automakers rely on them, Waslander told me. Using the terahertz band, “there’s got to be some trade-offs,” he speculated, such as lower measurement accuracy or higher absorption rates. In other words, while Teradar boasts the upsides of both radar and lidar, it may come with some of their downsides, too.

Another point in Teradar’s favor is that it doesn’t use a lens at all — there’s nothing to fog, freeze, or salt over. The sensor could help address a fundamental assumption of autonomy — as Juergen put it, “if you transfer responsibility from the human to a machine, it must be better than a human.” There are “very good solutions on the road,” he went on. “The question is, can they handle every weather or every use case? And the answer is no, they cannot.” Until sensors can demonstrate matching or exceeding human performance in snowy conditions — whether through a combination of lidar, cameras, and radar, or through a new technology such as Teradar’s Summit sensor — this will remain true.

If driving in winter weather can eventually be automated at scale, it could theoretically save thousands of lives. Until then, you might still consider using that empty parking lot nearby to brush up on your brake pumping.

Otherwise, there’s always Phoenix; I’ve heard it’s pleasant this time of year.

Current conditions: After a brief reprieve of temperatures hovering around freezing, the Northeast is bracing for a return to Arctic air and potential snow squalls at the end of the week • Cyclone Fytia’s death toll more than doubled to seven people in Madagascar as flooding continues • Temperatures in Mongolia are plunging below 0 degrees Fahrenheit for the rest of the workweek.

Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum suggested the Supreme Court could step in to overturn the Trump administration’s unbroken string of losses in all five cases where offshore wind developers challenged its attempts to halt construction on turbines. “I believe President Trump wants to kill the wind industry in America,” Fox Business News host Stuart Varney asked during Burgum’s appearance on Tuesday morning. “How are you going to do that when the courts are blocking it?” Burgum dismissed the rulings by what he called “court judges” who “were all at the district level,” and said “there’s always the possibility to keep moving that up through the chain.” Burgum — who, as my colleague Robinson Meyer noted last month, has been thrust into an ideological crisis over Trump’s actions toward Greenland — went on to reiterate the claims made in a Department of Defense report in December that sought to justify the halt to all construction on offshore turbines on the grounds that their operation could “create radar interference that could represent a tremendous threat off our highly populated northeast coast.” The issue isn’t new. The Obama administration put together a task force in 2011 to examine the problem of “radar clutter” from wind turbines. The Department of Energy found that there were ways to mitigate the issue, and promoted the development of next-generation radar that could see past turbines.

The Trump administration, meanwhile, is facing accusations of violating the Constitution with its orders to keep coal-fired power stations operating past planned retirement. By mandating their coal plants stay open, two electrical cooperatives in Colorado said the Energy Department’s directive “constitutes both a physical taking and a regulatory taking” of property by the government without just compensation or due process, Utility Dive reported.

Back in December, the promise of a bipartisan deal on permitting reform seemed possible as the SPEED Act came up for a vote in the House. At the last minute, however, far-right Republicans and opponents of offshore wind leveraged their votes to win an amendment specifically allowing President Donald Trump to continue his attempts to kill off the projects to build turbines off the Eastern Seaboard. With key Democrats in the Senate telling Heatmap’s Jael Holzman that their support hinged on legislation that did the opposite of that, the SPEED Act stalled out. Now a new bipartisan bill aims to rectify what went wrong. The FREEDOM Act — an acronym for “Fighting for Reliable Energy and Ending Doubt for Open Markets” — would prevent a Republican administration from yanking permits from offshore wind or a Democratic one from going after already-licensed oil and gas projects, while setting new deadlines for agencies to speed up application reviews. I got an advanced copy of the bill Monday night, so you can read the full piece on it here on Heatmap.

One element I didn’t touch on in my story is what the legislation would do for geothermal. Next-generation geothermal giant Fervo Energy pulled off its breakthrough in using fracking technology to harness the Earth’s heat in more places than ever before just after the Biden administration completed work on its landmark clean energy bills. As a result, geothermal lost out on key policy boosts that, for example, the next-generation nuclear industry received. The FREEDOM Act would require the government to hold twice as many lease sales on federal lands for geothermal projects. It would also extend the regulatory shortcuts the oil and gas industry enjoys to geothermal companies.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

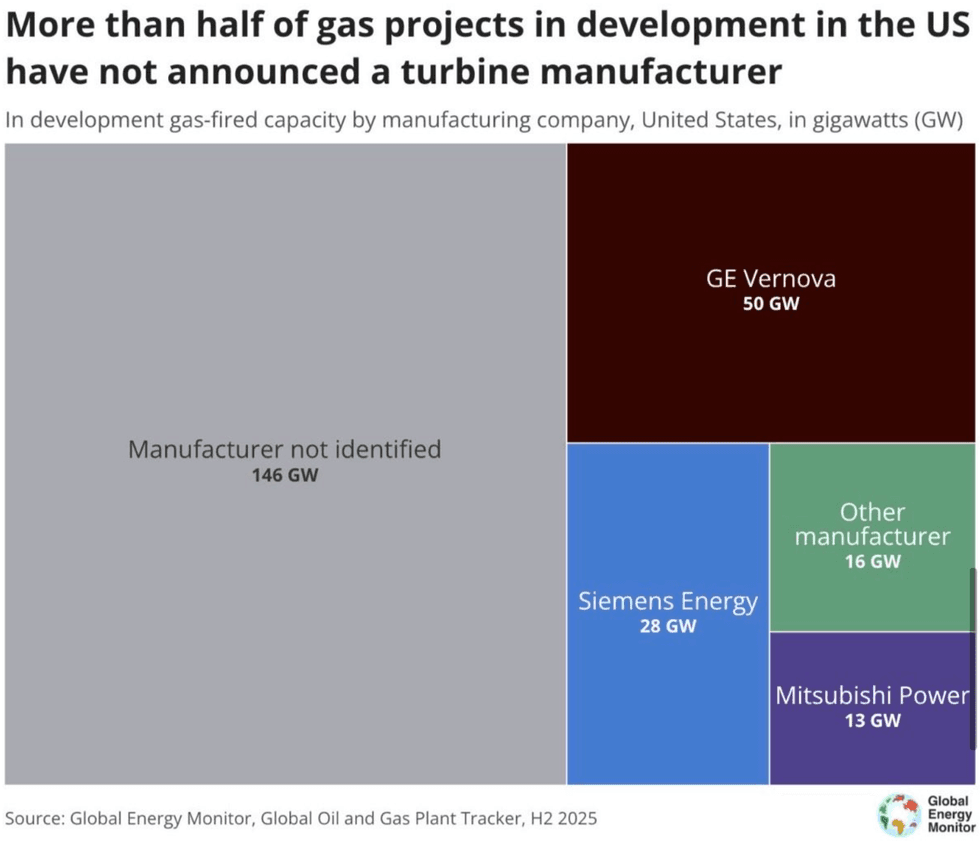

Take a look at the above chart. In the United States, new gas power plants are surging to meet soaring electricity demand. At last count, two thirds of projects currently underway haven’t publicly identified which manufacturer is making their gas turbines. With the backlog for turbines now stretching to the end of the decade, Siemens Energy wants to grow its share of booming demand. The German company, which already boasts the second-largest order book in the U.S. market, is investing $1 billion to produce more turbines and grid equipment. “The models need to be trained,” Christian Bruch, the chief executive of Siemens Energy, told The New York Times. “The electricity need is going to be there.”

While most of the spending is set to go through existing plants in Florida and North Carolina, Siemens Energy plans to build a new factory in Mississippi to produce electric switchgear, the equipment that manages power flows on the grid. It’s hardly alone. In September, Mitsubishi announced plans to double its manufacturing capacity for gas turbines over the next two years. After the announcement, the Japanese company’s share price surged. Until then, investors’ willingness to fund manufacturing expansions seemed limited. As Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin put it, “Wall Street has been happy to see developers get in line for whatever turbines can be made from the industry’s existing facilities. But what happens when the pressure to build doesn’t come from customers but from competitors?” Siemens just gave its answer.

At his annual budget address in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro touted Amazon’s plans to invest $20 billion into building two data center campuses in his state. But he said it’s time for the state to become “selective about the projects that get built here.” To narrow the criteria, he said developers “must bring their own power generation online or fully fund new generation to meet their needs — without driving up costs for homeowners or businesses.” He insisted that data centers conserve more water. “I know Pennsylvanians have real concerns about these data centers and the impact they could have on our communities, our utility bills, and our environment,” he said, according to WHYY. “And so do I.” The Democrat, who is running for reelection, also called on utilities to find ways to slash electricity rates by 20%.

For the first time, every vehicle on Consumer Reports’ list of top picks for the year is a hybrid (or available as one) or an electric vehicle. The magazine cautioned that its endorsement extended to every version of the winning vehicles in each category. “For example, our pick of the Honda Civic means we think the gas-only Civic, the hybrid, and the sporty Si are all excellent. But for some models, we emphasize the version that we think will work best for most people.” But the publication said “the hybrid option is often quieter and more refined at speed, and its improved fuel efficiency usually saves you money in the long term.”

Elon Musk wants to put data centers in space. In an application to the Federal Communications Commission, SpaceX laid out plans to launch a constellation of a million solar-powered data centers to ease the strain the artificial intelligence boom is placing on the Earth’s grids. Each data center, according to E&E News, would be 31 miles long and operate more than 310 miles above the planet’s surface. “By harnessing the Sun’s abundant, clean energy in orbit — cutting emissions, minimizing land disruption, and reducing the overall environmental costs of grid expansion — SpaceX’s proposed system will enable sustainable AI advancement,” the company said in the filing.