You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

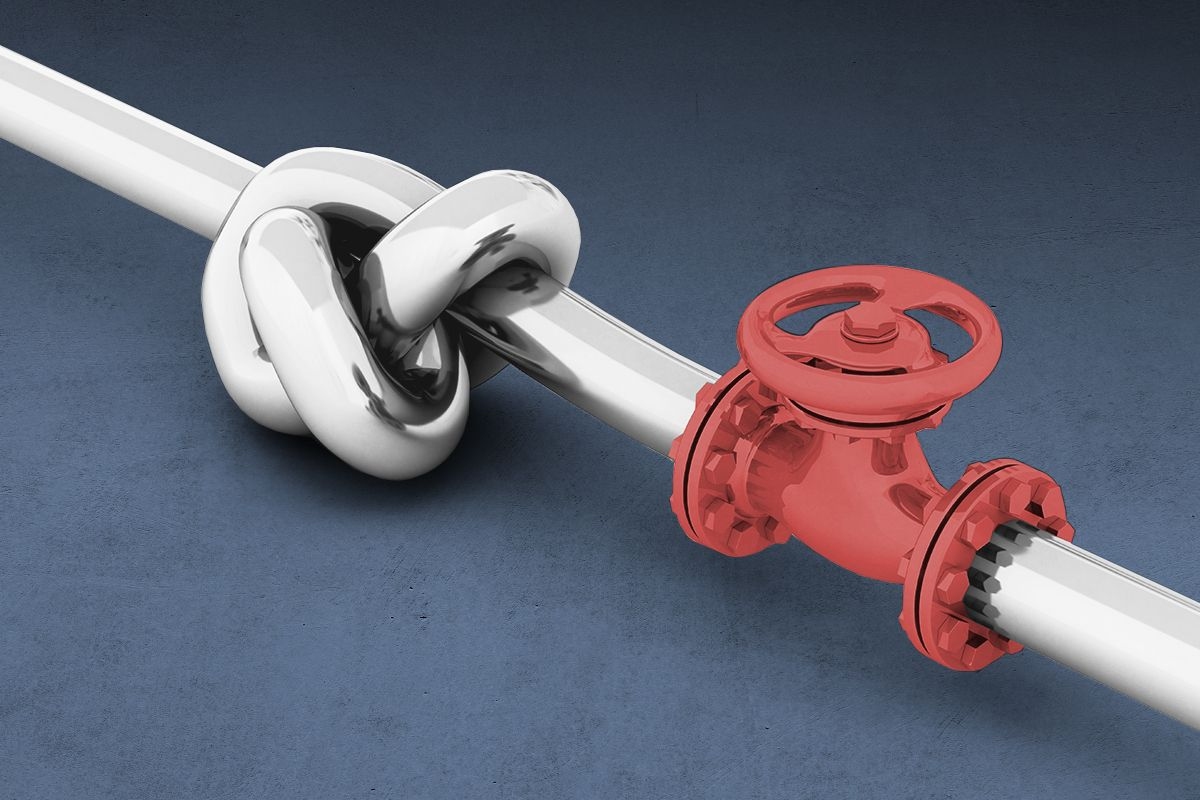

Investors are betting on gas to meet the U.S.’s growing electricity demand. Turbine manufacturers, however, have other plans.

Thanks to skyrocketing investment in data centers, manufacturing, and electrification, American electricity demand is now expected to grow nearly 16% over the next four years, a striking departure from two decades of tepid load growth. Providing the energy required to meet this new demand may require a six-fold increase in the pace of building new generation and new transmission ― hence bipartisan calls for an energy “abundance” agenda and, where the Trump administration is concerned, dreams of “energy dominance.” This is the next frontier in the fight between clean energy and fossil energy. Which one will end up fueling all of this new demand?

Investors are betting on natural gas. If these demand projections aren’t just hot air, the energy resource fueling all this growth will be, so to speak. Where actually deploying new gas power is concerned, however, there’s a big problem: All major gas turbine manufacturers, slammed by massive order growth, now have backlogs for new turbine deliveries stretching out to 2029 or later. Energy news coverage has mentioned these potential project development delays sometimes in passing, sometimes not at all. But this looming mismatch between gas power demand and turbine supply is a real problem for the grid and everyone who depends on it.

Taking a closer look at the investment plans of GE Vernova, the U.S.’s leading gas turbine manufacturer, suggests that, even as energy demand ramps up, these delays will persist. Rather than potentially overinvest in the face of rising demand and suffer the consequence of falling prices, GE Vernova and its competitors are committed to capital discipline, lengthening their order book, and defending shareholder value. Their reluctance to invest, while justified in some part by the nature and history of the industry, will threaten policymakers’ push for energy abundance ― to say nothing about economic growth or innovation.

Meanwhile, supply chain shortages will constrain the growth of clean energy generation. Inadequate investment in gas and an insufficient buildout of renewables in the face of unprecedented demand growth ― these are a toxic cocktail for the American energy system. Forget visions of an all-of-the-above energy strategy. How about none of the above?

Energy project developers, utilities, and investors have already started adjusting their gas buildout expectations and timelines. NextEra CEO John Ketchum stated in an earnings call that new gas projects “won’t be available at scale until 2030, and then only in certain pockets of the U.S.” That’s due not only to turbine queues, but also to an historically sluggish and increasingly expensive gas project development environment. “The country is starting from a standing start,” he added. “This is an industry that really hasn’t seen any active development or construction in years … all of that puts pressure on cost.”

Even in Texas, where lawmakers created the Texas Energy Fund to provide $10 billion of concessional financing to new gas power plants, delays are biting developers’ balance sheets. Just last week, private developer Engie withdrew two loan applications for gas peaker plant projects due to “equipment procurement constraints.” There’s no other way to spin it — the turbines are the problem.

Given that wait times and reservation payments drain developers’ liquidity and increase their financing costs, energy giants are trying to cut the line. Chevron is partnering with GE Vernova to develop up to 4 gigawatts of gas power plants for data centers. NextEra also announced a partnership with GE Vernova, through which the two companies will co-develop and co-own “multiple gigawatts” of natural gas power plants.

It’s safe to say that GE Vernova’s power division is riding high. The company’s investor materials suggest a heady growth trajectory. Gas turbine equipment orders rose 66% between 2023 and 2024, from 41 turbines to 68 turbines. Those 68 turbines represented about 20 gigawatts of capacity, double 2023’s order book. Developers reserved 9 gigawatts more of turbines; those reservations will turn into contracted production orders by 2026. At this point, 90% of GE Vernova’s total order volumes are in its backlog; for its power division, that represents almost $74 billion of equipment delivery and service contracts.

The company plans to invest $300 million into its gas power business in the next two years. And CEO Scott Strazik is pitching investors on continued growth. “Given our expansion plans to produce 70 to 80 heavy-duty gas turbines per year beginning in the second half of 2026, up from 48 this year, we are positioning to meet this demand. We expect to grow our gas equipment backlog considerably in 2025, even as we ramp to ship approximately 20 gigawatts annually starting in 2027, and expect to remain at that level going forward,” he said on the company’s Q4 earnings call.

That last sentence should give readers pause: GE Vernova has plans to build no more than 20 gigawatts of turbines per year, and developers that miss the cutoffs will just have to queue up for the next year’s order book. Why the limit?

Strazik laid out two key reasons. First, he’s looking for developers’ “receptivity to pay for what I will call premium slots” in 2028 and 2029, to “capture every dollar of price with the precious slots available,” as he told investors during a different presentation in December. GE Vernova’s annual report, which it released in February, refers to this strategy ― inviting desperate developers to bid up the price of scarce turbines ― as “expanding margins in backlog.” Second, the company remains hampered by supply constraints, particularly on ramping up its new heavy-duty and H-class turbines. There are real limits to how much more GE Vernova can build, and how quickly.

But over the longer term, it looks like GE Vernova is intentionally committing more to capital discipline rather than to broader capacity expansion. The company has $1.7 billion in free cash flow, a third of which it will return to shareholders through dividends and stock buybacks. And Strazik wants to avoid using the rest to underwrite what he sees as dangerous overcapacity that could threaten GE Vernova’s profitability. “I think we have to be very thoughtful to make sure that we don't add too much capacity, even though we are starting to sell slots into 2029,” he said during the investor update. “We're going to continue to be very sequential on how we invest.”

Strazik’s current strategy prioritizes productivity and efficiency improvements at GE Vernova’s existing plant in South Carolina over building new manufacturing facilities. Some capacity expansion, sure ― but no new plant. “Concrete's expensive, cranes are difficult,” he told investors. The company’s main competitors abroad, Mitsubishi and Siemens, have the same backlogs, and Mitsubishi, at least, is responding with a similarly measured strategy. Mitsubishi CFO Hisato Kozawa is open to some degree of capacity expansion, but maintains that Mitsubishi can only increase capacity “in a very planned manner with discipline. And if we need more capacity, we may want to first improve the rotation of the capacity.”

To the CEOs of all three companies, history would likely seem to justify this discipline. In 2017 and 2018, years of investment into capacity expansion coincided with a near-total collapse in global demand for gas turbines. This market crash was most likely the combined effect of low energy demand growth, energy efficiency improvements, continued use of coal power across Asia, the growing share of renewable energy on the grid, and investors’ realization that solar and wind energy could meaningfully undercut gas on price. All three companies laid off tens of thousands of employees, and the crash contributed to the complete breakup of General Electric and its partial spin-off into GE Vernova last year.

These gas turbine manufacturers are also some of the world’s leading wind turbine blade manufacturers, and a similar fate befell that sector in the past decade. Large-scale capacity expansion and competition for contracts drove down costs and margins across the supply chain — only for those to move sharply in reverse when supply chains froze up during the pandemic and interest rates shot up in 2023. Now offshore wind projects are plagued with problems and, at least in the U.S., President Trump’s de facto moratorium on offshore wind development has further reduced the sector’s ability to bounce back. These companies have been burned before. It only makes sense not to repeat past mistakes.

Combined-cycle gas turbines are complex machines, similar to airline engines in their intricacy and in the extensive global supply chains required to produce them. But their leading producers, afraid of getting over their skis, won’t undertake the massive upfront investments required to increase their long-term production capacity. Where does this leave the energy transition?

Bankers and energy project developers alike can see the writing on the wall. Beth Waters, managing director for project finance at Japanese bank MUFG, has insisted that “renewables have to be part of the electricity mix. It cannot just be gas-fired.” NextEra’s Ketchum has said the same: “Renewables are here today,” he stated during the latest earnings call — unlike gas. Jigar Shah, the head of the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office under President Biden, wrote on LinkedIn about his confidence that “batteries will be deployed at 10X the capacity of combined cycle natural gas units over the next 4 years.” Major utility companies, for their part, still have large clean energy procurement targets in their integrated resource plans. The smart money is clearly betting that an “all-of-the-above” energy deployment strategy will be better than eschewing any particular energy source.

They’re being optimistic. Not only does new utility-scale renewable energy take years to build, there’s also not yet enough transmission and longer-term energy storage on the grid to balance the variance in existing solar and wind resources. That prevents solar and wind from providing the kind of 24-hour stable power that corporate and industrial customers demand. Expanding energy storage and transmission resources will depend not just on regulatory reforms to permitting and interconnection, but also on resolving the severe bottleneck in grid transformers, where analysts believe capacity expansion has also failed to meet roaring demand, resulting in wait times of three to four years. (GE Vernova and Siemens build grid transformers too.) The status quo has left hundreds of gigawatts of clean energy projects across the country stuck in a regulatory and financing limbo, and the grid issues that tie up clean energy development will further constrain gas power growth.

To be sure, President Trump’s “energy dominance” agenda seems to favor the development of clean firm energy resources, such as nuclear and enhanced geothermal, to cut through the literal gridlock. The gas turbine manufacturers, all of which build steam turbines for nuclear power, stand to benefit from interest in restarting and upgrading now-shuttered plants. But building new nuclear projects currently takes at least 10 years, if not more. The singular new nuclear project built in the U.S. in the past three decades was completed seven years late and almost $20 billion over budget.

Enhanced geothermal might fare somewhat better ― its drilling technology comes straight from the fracking sector, and the pilot projects of companies like Fervo are achieving impressive heat and electricity production targets. Still, to turn heat into electricity, Fervo needs turbines, too. While enhanced geothermal projects need organic Rankine cycle turbines, as opposed to the combined-cycle gas turbines used in gas power plants, commodity market strategist Alex Turnbull theorizes that the commonalities between the two will threaten geothermal developers with the same delays and bottlenecks. (Fervo’s turbine supplier is an Italian subsidiary of Mitsubishi.)

The tech giants building data centers are already investing in new power ― but if neither nuclear nor geothermal can be deployed at scale in the absence of massive policy support, then that leaves tech companies paying for whatever energy sources their regional electricity grid relies on in the meantime. As Cy McGeady, a fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told Heatmap last year, “Nobody is willing to not build the next data center because of inability to access renewables.” But drawing so much from existing resources ― mostly gas, but also nuclear ― without building sufficient new power leaves less for every other energy consumer.

Policymakers on both sides of the aisle have their work cut out for them to avoid a crisis born of a failure to build any energy resource adequately: They must execute a thorough grid overhaul while also punching through the specific supply chain bottlenecks that prevent energy generation from being built quickly. Regardless of energy demand projections, these are goals worth pursuing. They advance grid reliability, energy affordability, and decarbonization, as well as accommodate any necessary energy supply growth.

Still, it’s worth questioning the prevailing narratives around load growth. It’s not clear how much energy data centers in particular will actually require. Not only have innovations like DeepSeek challenged market assumptions about tech companies’ investment requirements, but recent research also suggests that load growth projections could fall significantly if data centers’ energy demand were more flexible. Not to mention that data center developers often make duplicate interconnection requests with different utilities to maximize their chance of securing a power agreement.

Our energy grid will need a lot less hot air if data center demand goes up in smoke ― and that would be a relief for American consumers and the climate alike. But courting a gas turbine crisis should itself give policymakers pause. The fact that our energy system is at a point where neither turbines nor transformers nor transmission is available in sufficient capacity to meet any policymaker’s vision of energy abundance suggests that our leaders must reorient the government’s relationship to industry. During periods of economic uncertainty, capital discipline might appear rational, even profitable. But the power sector’s profits are, through rising energy bills and more frequent climate disasters, revealed to be everyone else’s costs. Between clean energy and fossil fuels — between what Americans need and what private industry can provide — the energy transition is shaping up to be, quite literally, a power struggle.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The state is poised to join a chorus of states with BYO energy policies.

With the backlash to data center development growing around the country, some states are launching a preemptive strike to shield residents from higher energy costs and environmental impacts.

A bill wending through the Washington State legislature would require data centers to pick up the tab for all of the costs associated with connecting them to the grid. It echoes laws passed in Oregon and Minnesota last year, and others currently under consideration in Florida, Georgia, Illinois, and Delaware.

Several of these bills, including Washington’s, also seek to protect state climate goals by ensuring that new or expanded data centers are powered by newly built, zero-emissions power plants. It’s a strategy that energy wonks have started referring to as BYONCE — bring your own new clean energy. Almost all of the bills also demand more transparency from data center companies about their energy and water use.

This list of state bills is by no means exhaustive. Governors in New York and Pennsylvania have declared their intent to enact similar policies this year. At least six states, including New York and Georgia, are also considering total moratoria on new data centers while regulators study the potential impacts of a computing boom.

“Potential” is a key word here. One of the main risks lawmakers are trying to circumvent is that utilities might pour money into new infrastructure to power data centers that are never built, built somewhere else, or don’t need as much energy as they initially thought.

“There’s a risk that there’s a lot of speculation driving the AI data center boom,” Emily Moore, the senior director of the climate and energy program at the nonprofit Sightline Institute, told me. “If the load growth projections — which really are projections at this point — don’t materialize, ratepayers could be stuck holding the bag for grid investments that utilities have made to serve data centers.”

Washington State, despite being in the top 10 states for data center concentration, has not exactly been a hotbed of opposition to the industry. According to Heatmap Pro data, there are no moratoria or restrictive ordinances on data centers in the state. Rural communities in Eastern Washington have also benefited enormously from hosting data centers from the earlier tech boom, using the tax revenue to fund schools, hospitals, municipal buildings, and recreation centers.

Still, concern has started to bubble up. A ProPublica report in 2024 suggested that data centers were slowing the state’s clean energy progress. It also described a contentious 2023 utility commission meeting in Grant County, which has the highest concentration of data centers in the state, where farmers and tech workers fought over rising energy costs.

But as with elsewhere in the country, it’s the eye-popping growth forecasts that are scaring people the most. Last year, the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, a group that oversees electricity planning in the region, estimated that data centers and chip fabricators could add somewhere between 1,400 megawatts and 4,500 megawatts of demand by 2030. That’s similar to saying that between one and four cities the size of Seattle will hook up to the region’s grid in the next four years.

In the face of such intimidating demand growth, Washington Governor Bob Ferguson convened a Data Center Working Group last year — made up of state officials as well as advisors from electric utilities, environmental groups, labor, and industry — to help the state formulate a game plan. After meeting for six months, the group published a report in December finding that among other things, the data center boom will challenge the state’s efforts to decarbonize its energy systems.

A supplemental opinion provided by the Washington Department of Ecology also noted that multiple data center developers had submitted proposals to use fossil fuels as their main source of power. While the state’s clean energy law requires all electricity to be carbon neutral by 2030, “very few data center developers are proposing to use clean energy to meet their energy needs over the next five years,” the department said.

The report’s top three recommendations — to maintain the integrity of Washington’s climate laws, strengthen ratepayer protections, and incentivize load flexibility and best practices for energy efficiency — are all incorporated into the bill now under discussion in the legislature. The full list was not approved by unanimous vote, however, and many of the dissenting voices are now opposing the data center bill in the legislature or asking for significant revisions.

Dan Diorio, the vice president of state policy for the Data Center Coalition, an industry trade group, warned lawmakers during a hearing on the bill that it would “significantly impact the competitiveness and viability of the Washington market,” putting jobs and tax revenue at risk. He argued that the bill inappropriately singles out data centers, when arguably any new facility with significant energy demand poses the same risks and infrastructure challenges. The onshoring of manufacturing facilities, hydrogen production, and the electrification of vehicles, buildings, and industry will have similar impacts. “It does not create a long-term durable policy to protect ratepayers from current and future sources of load growth,” he said.

Another point of contention is whether a top-down mandate from the state is necessary when utility regulators already have the authority to address the risks of growing energy demand through the ratemaking process.

Indeed, regulators all over the country are already working on it. The Smart Electric Power Alliance, a clean energy research and education nonprofit, has been tracking the special rate structures and rules that U.S. utilities have established for data centers, cryptocurrency mining facilities, and other customers with high-density energy needs, many of which are designed to protect other ratepayers from cost shifts. Its database, which was last updated in November, says that 36 such agreements have been approved by state utility regulators, mostly in the past three years, and that another 29 are proposed or pending.

Diario of the Data Center Coalition cited this trend as evidence that the Washington bill was unnecessary. “The data center industry has been an active party in many of those proceedings,” he told me in an email, and “remains committed to paying its full cost of service for the energy it uses.” (The Data Center Coalition opposed a recent utility decision in Ohio that will require data centers to pay for a minimum of 85% of their monthly energy forecast, even if they end up using less.)

One of the data center industry’s favorite counterarguments against the fear of rising electricity is that new large loads actually exert downward pressure on rates by spreading out fixed costs. Jeff Dennis, who is the executive director of the Electricity Customer Alliance and has worked for both the Department of Energy and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, told me this is something he worries about — that these potential benefits could be forfeited if data centers are isolated into their own ratemaking class. But, he said, we’re only in “version 1.5 or 2.0” when it comes to special rate structures for big energy users, known as large load tariffs.

“I think they’re going to continue to evolve as everybody learns more about how to integrate large loads, and as the large load customers themselves evolve in their operations,” he said.

The Washington bill passed the Appropriations Committee on Monday and now heads to the Rules Committee for review. A companion bill is moving through the state senate.

Plus more of the week’s top fights in renewable energy.

1. Kent County, Michigan — Yet another Michigan municipality has banned data centers — for the second time in just a few months.

2. Pima County, Arizona — Opposition groups submitted twice the required number of signatures in a petition to put a rezoning proposal for a $3.6 billion data center project on the ballot in November.

3. Columbus, Ohio — A bill proposed in the Ohio Senate could severely restrict renewables throughout the state.

4. Converse and Niobrara Counties, Wyoming — The Wyoming State Board of Land Commissioners last week rescinded the leases for two wind projects in Wyoming after a district court judge ruled against their approval in December.

A conversation with Advanced Energy United’s Trish Demeter about a new report with Synapse Energy Economics.

This week’s conversation is with Trish Demeter, a senior managing director at Advanced Energy United, a national trade group representing energy and transportation businesses. I spoke with Demeter about the group’s new report, produced by Synapse Energy Economics, which found that failing to address local moratoria and restrictive siting ordinances in Indiana could hinder efforts to reduce electricity prices in the state. Given Indiana is one of the fastest growing hubs for data center development, I wanted to talk about what policymakers could do to address this problem — and what it could mean for the rest of the country. Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Can you walk readers through what you found in your report on energy development in Indiana?

We started with, “What is the affordability crisis in Indiana?” And we found that between 2024 and 2025, residential consumers paid on average $28 more per month on their electric bill. Depending on their location within the state, those prices could be as much as $49 higher per month. This was a range based on all the different electric utilities in the state and how much residents’ bills are increasing. It’s pretty significant: 18% average across the state, and in some places, as high as 27% higher year over year.

Then Synapse looked into trends of energy deployment and made some assumptions. They used modeling to project what “business as usual” would look like if we continue on our current path and the challenges energy resources face in being built in Indiana. What if those challenges were reduced, streamlined, or alleviated to some degree, and we saw an acceleration in the deployment of wind, solar, and battery energy storage?

They found that over the next nine years, between now and 2035, consumers could save a total of $3.6 billion on their energy bills. We are truly in a supply-and-demand crunch. In the state of Indiana, there is a lot more demand for electricity than there is available electricity supply. And demand — some of it will come online, some of it won’t, depending on whose projections you’re looking at. But suffice it to say, if we’re able to reduce barriers to build new generation in the state — and the most available generation is wind, solar, and batteries — then we can actually alleviate some of the cost concerns that are falling on consumers.

How do cost concerns become a factor in local siting decisions when it comes to developing renewable energy at the utility scale?

We are focused on state decisionmakers in the legislature, the governor’s administration, and at the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission, and there’s absolutely a conversation going on there about affordability and the trends that they’re seeing across the state in terms of how much more people are paying on their bills month to month.

But here lies the challenge with a state like Indiana. There are 92 counties in the state, and each has a different set of rules, a different process, and potentially different ways for the local community to weigh in. If you’re a wind, solar, or battery storage developer, you are tracking 92 different sets of rules and regulations. From a state law perspective, there’s little recourse for developers or folks who are proposing projects to work through appeals if their projects are denied. It’s a very risky place to propose a project because there are so many ways it can be rejected or not see action on an application for years at a time. From a business perspective, it’s a challenging place to show that bringing in supply for Indiana’s energy needs can help affordability.

To what extent do you think data centers are playing a role in these local siting conflicts over renewable energy, if any?

There are a lot of similarities with regard to the way that Indiana law is set up. It’s very much a home rule state. When development occurs, there is a complex matrix of decision-making at the local level, between a county council and municipalities with jurisdiction over data centers, renewable energy, and residential development. You also have the land planning commissions that are in every county, and then the boards of zoning appeals.

So in any given county, you have anywhere between three and four different boards or commissions or bodies that have some level of decision-making power over ordinances, over project applications and approvals, over public hearings, over imposing or setting conditions. That gives a local community a lot of levers by which a proposal can get consideration, and also be derailed or rejected.

You even have, in one instance recently, a municipality that disagreed with the county government: The municipality really wanted a solar project, and the county did not. So there can be tension between the local jurisdictions. We’re seeing the same with data centers and other types of development as well — we’ve heard of proposals such as carbon capture and sequestration for wells or test wells, or demonstration projects that have gotten caught up in the same local decision-making matrix.

Where are we at with unifying siting policy in Indiana?

At this time there is no legislative proposal to reform the process for wind, solar, and battery storage developers in Indiana. In the current legislative session, there is what we’re calling an affordability bill, House Bill 1002, that deals with how utilities set rates and how they’re incentivized to address affordability and service restoration. That bill is very much at the center of the state energy debate, and it’s likely to pass.

The biggest feature of a sound siting and permitting policy is a clear, predictable process from the outset for all involved. So whether or not a permit application for a particular project gets reviewed at a local or a state level, or even a combination of both — there should be predictability in what is required of that applicant. What do they need to disclose? When do they need to disclose it? And what is the process for reviewing that? Is there a public hearing that occurs at a certain period of time? And then, when is a decision made within a reasonable timeframe after the application is filed?

I will also mention the appeals processes: What are the steps by which a decision can be appealed, and what are the criteria under which that appeal can occur? What parameters are there around an appeal process? That's what we advocate for.

In Indiana, a tremendous step in the right direction would be to ensure predictability in how this process is handled county to county. If there is greater consistency across those jurisdictions and a way for decisions to at least explain why a proposal is rejected, that would be a great step.

It sounds like the answer, on some level, is that we don’t yet know enough. Is that right?

For us, what we’re looking for is: Let’s come up with a process that seems like it could work in terms of knowing when a community can weigh in, what the different authorities are for who gets to say yes or no to a project, and under what conditions and on what timelines. That will be a huge step in the right direction.