You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

And how ordinary Americans will pay the price.

No one seems to know exactly how many employees have been laid off from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration — or, for that matter, what offices those employees worked at, what jobs they held, or what regions of the country will be impacted by their absence. We do know that it was a lot of people; about 10% of the roughly 13,000 people who worked at the agency have left since Donald Trump took office, either because they were among the 800 or so probationary employees to be fired late last month or because they resigned.

“I don’t have the specifics as to which offices, or how many people from specific geographic areas, but I will reiterate that every one of the six [NOAA] line offices and 11 of the staff offices — think of the General Counsel’s Office or the Legislative Affairs Office — all 11 of those staff offices have suffered terminations,” Rick Spinrad, who served as the NOAA administrator under President Joe Biden, told reporters in a late February press call. (At least a few of the NOAA employees who were laid off have since been brought back.)

Democratic Representative Jared Huffman of California, the ranking member of the House Natural Resources Committee, said in recent comments about the NOAA layoffs, “This is going to have profound negative consequences on the day-to-day lives of Americans.” He added, “This is something that [Elon Musk’s government efficiency team] just doesn’t even understand. They simply have no idea what they are doing and how it’s hurting people.”

There is the direct harm to hard-working employees who have lost their jobs, of course. But there is also a more existential problem: Part of what is driving the layoffs is a belief by those in power that the agency is “one of the main drivers of the climate change alarm industry,” according to the Project 2025 playbook. As one recently fired NOAA employee put it, “the goal is destruction,” and climate science is one of the explicit targets.

NOAA is a multifaceted organization, and monitoring climate change is far from its only responsibility. The agency researches, protects, and restores America’s fisheries, including through an enforcement arm that combats poaching; it explores the deep ocean and governs seabed mining; and its Commissioned Officer Corps is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States, alongside the Army, Marines Corps, and Coast Guard. But many of its well-known responsibilities almost inevitably touch climate change, from the National Hurricane Center’s forecasts and warnings to drought tools for farmers to heat forecasts from the National Weather Service issued on hot summer days. Cutting climate science out of NOAA would have immediate — and in some cases, deadly — impacts on regular Americans.

And it’s likely this is only the beginning of the purge. Project 2025 calls for the complete disbanding of NOAA. Current agency employees have reportedly been told to brace for “a 50% reduction in staff” as part of Elon Musk’s government efficiency campaign. Another 1,000 terminations are expected this week, bringing the total loss at NOAA to around 20% of its staff.

Here are just a few of the ways those layoffs are already impacting climate science.

NOAA collects more than 20 terabytes of environmental data from Earth and space daily, and through its paleoclimatology arm, it has reconstructed climate data going back 100 million years. Not even Project 2025 calls for the U.S. to halt its weather measurements entirely; in fact, Congress requires the collection of a lot of standard climate data.

But the NOAA layoffs are hampering those data collection efforts, introducing gaps and inconsistencies. For example, staffing shortages have resulted in the National Weather Service suspending weather balloon launches from Kotzebue, Alaska — and elsewhere — “indefinitely.” The Trump administration is also considering shuttering a number of government offices, including several of NOAA’s weather monitoring stations. Repairs of monitors and sensors could also be delayed by staff cuts and funding shortfalls — or not done at all.

Flawed and incomplete data results in degraded and imprecise forecasts. In an era of extreme weather, the difference of a few miles or degrees can be a matter of life or death.

In the case of climate science specifically, which looks at changes over much longer timescales than meteorology, “I think you could do science with the data we have now, if we can preserve it,” Flavio Lehner, a climate scientist at Cornell University who uses NOAA data in his research, told me.

But therein lies the next problem: the threat that the government could take NOAA climate data down entirely.

Though data collection is in many cases mandated by Congress, Congress does not require that the public have access to that data. Though NOAA’s climate page is still live, the Environmental Protection Agency has already removed from its website the Keeling Curve tracker, the daily global atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration measurement that Drilled notes is “one of the longest-running data projects in climate science.” Many other government websites that reference climate change have also gone dark. Solutions are complicated — “downloading” NOAA to preserve it, for example, would cost an estimated $500,000 in storage per month for an institution to host it.

“At the end of the day, if you’re a municipality or a community and you realize that some of these extreme weather events are becoming more frequent, you’ll want to adapt to it, whether you think it’s because of climate change or not,” Lehner said. “People want to have the best available science to adapt, and I think that applies to Republicans and Democrats and all kinds of communities across the country.” But if the Trump administration deletes NOAA websites, or the existing measurements it’s putting out are of poor quality, “it’s not going to be the best possible science to adapt moving forward,” Lehner added.

I wouldn’t want to be a NOAA scientist with the word “climate” attached to my title or work. The Trump administration has shown itself to be ruthless in eliminating references to words or concepts it opposes, including flagging pictures of the Enola Gay WWII airplane for removal from the Defense Department’s website in an effort to cut all references to the LGBT community from the agency.

“Climate science” is another Trump administration boogey-word, but the NOAA scientists who remain employed by the agency after the layoffs will still have to deal with the realities of a world warmed by the burning of fossil fuels. “Ultimately, what we’re dealing with are changes in our environment that impact ecosystems and humans, and whether you think these changes are driven by humans or not, it’s something that can now be seen in data,” Lehner told me. “From that perspective, I find it hard to believe that this is not something that people [in the government] are interested in researching.”

Government scientists who want to track things like drought or the rapid intensification of hurricanes going forward will likely have to do so without using the word “climate.” Lehner, for example, recalled submitting a proposal to work with the Bureau of Reclamation on the climate change effects on the Colorado River during the first Trump administration and being advised to replace words like “climate change” with more politically neutral language. His team did, and the project ultimately got funded, though Lehner couldn’t say if that was only because of the semantics. It seems likely, though, that Trump 2.0 will be even stricter in CTRL + F’ing “climate” at NOAA and elsewhere.

Climate research will continue in some form at NOAA, if only because that’s the reality of working with data of a warming planet. But scientists who don’t lose their jobs in the layoffs will likely find themselves wasting time on careful doublespeak so as not to attract unwanted attention.

Another major concern with the NOAA layoffs is the loss of expert knowledge. Many NOAA offices were already lean and understaffed, and only one or two employees likely knew how to perform certain tasks or use certain programs. If those experts subsequently lose their jobs, decades of NOAA know-how will be lost entirely.

As one example, late last year, NOAA updated its system to process grants, causing delays as its staff learned how to use the new program. Given the new round of layoffs, the odds are that some of the employees who may have finally figured out how to navigate the new procedure may have been let go. The problem gets even worse when it comes to specialized knowledge.

“Some of the expertise in processing [NOAA’s] data has been abruptly lost,” Lehner told me. “The people who are still there are scrambling to pick up and learn how to process that data so that it can then be used again.”

The worst outcome of the NOAA layoffs, though, is the extensive damage it does to the institution’s future. Some of the brightest, most enthusiastic Americans at NOAA — the probationary employees with under a year of work — are already gone. What’s more, there aren’t likely to be many new openings at the agency for the next generation of talent coming up in high school and college right now.

“We have an atmospheric science program [at Cornell University] where students have secured NOAA internships for this summer and were hoping to have productive careers, for example, at the National Weather Service, and so forth,” Lehner said. “Now, all of this is in question.”

That is hugely detrimental to NOAA’s ability to preserve the institutional knowledge of outgoing or retiring employees, or to build and advance a workforce of the future. It’s impossible to measure how many people ultimately leave the field or decide to pursue a different career because of the changes at NOAA — damage that will not be easily reversed under a new administration. “It’s going to take years for NOAA to recover the trust of the next generation of brilliant environmental scientists and policymakers,” Spinrad, the former NOAA administrator, said.

Climate change is a global problem, and NOAA has historically worked with partner agencies around the world to better understand the impacts of the warming planet. Now, however, the Trump administration has ordered NOAA employees to stop their international work, and employees who held roles that involved collaboration with partners abroad could potentially become targets of Musk’s layoffs. Firing those employees would also mean severing their relationships with scientists in international offices — offices that very well could have been in positions to help protect U.S. citizens with their research and data.

As the U.S. continues to isolate itself and the NOAA layoffs continue, there will be cascading consequences for climate science, which is inherently a collaborative field. “When the United States doesn’t lead [on climate science], two things happen,” Craig McLean, a former assistant administrator of NOAA for research, recently told the press. “Other nations relax their own spending in these areas, and the world’s level of understanding starts to decline,” and “countries who we may not have as collegial an understanding with,” such as China, could ostensibly step in and “replace the United States and its leadership.”

That leaves NOAA increasingly alone, and Americans of all political stripes will suffer as a result. “The strategy to erase data and research, to pull the rug from under activism — it’s time-tested,” Lehner, the Cornell climate scientist, said. “But that’s where it’s very infuriating because NOAA’s data is bipartisanly useful.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Batteries can only get so small so fast. But there’s more than one way to get weight out of an electric car.

Batteries are the bugaboo. We know that. Electric cars are, at some level, just giant batteries on wheels, and building those big units cheaply enough is the key to making EVs truly cost-competitive with fossil fuel-burning trucks and cars and SUVs.

But that isn’t the end of the story. As automakers struggle to lower the cost to build their vehicles amid a turbulent time for EVs in America, they’re looking for any way to shave off a little expense. The target of late? Plain old wires.

Last month, when General Motors had to brace its investors for billions in losses related to curtailing its EV efforts and shifting factories back to combustion, it outlined cost-saving measures meant to get things moving in the right direction. While much of the focus was on using battery chemistries like lithium ion phosphate, otherwise known as LFP, that are cheaper to build, CEO Mary Barra noted that the engineers on every one of the company’s EVs were working “to take out costs beyond the battery,” of which cutting wiring will be a part.

They are not alone in this obsession. Coming into a do-or-die year with the arrival of the R2 SUV, Rivian said it had figured out how to cut two miles of wires out of the design, a coup that also cuts 44 pounds from the vehicle’s weight (this is still a 5,000-pound EV, but every bit counts). Ford has become obsessed with figuring out smarter and cheaper ways for its money-hemorrhaging EV division to build cars; the company admitted, after tearing down a Tesla Model 3 to look inside, that its Mustang Mach-E EV had a mile of extra and possibly unnecessary wiring compared to its rival.

A bunch of wires sounds like an awfully mundane concern for cars so sophisticated. But while every foot adds cost and weight, the obsession with stripping out wiring is about something deeper — the broad move to redefine how cars are designed and built.

It so happens that the age of the electric vehicle is also the age of the software-defined car. Although automobiles were born as purely mechanical devices, code has been creeping in for decades, and software is needed to manage the computerized fuel injection systems and on-board diagnostic systems that explain why your Check Engine light is illuminated. Tesla took this idea to extremes when it routed the driver’s entire user interface through a giant central touchscreen. This was the car built like a phone, enabling software updates and new features to be rolled out years after someone bought the car.

As Tesla ruled the EV industry in the 2010s, the smartphone-on-wheels philosophy spread. But it requires a lot of computing infrastructure to run a car on software, which adds complexity and weight. That’s why carmakers have spent so much time in the past couple of years talking about wires. Their challenge (among many) is to simplify an EV’s production without sacrificing any of its capability.

Consider what Rivian is attempting to do with the R2. As InsideEVs explains, electric cars have exploded in their need for electronic control units, the embedded computing brains that control various systems. Some models now need more than 100 to manage all the software-defined components. Rivian managed to sink the number to just seven, and thus shave even more cost off the R2, through a “zonal” scheme where the ECUs control all the systems located in their particular region of the vehicle.

Compared to an older, centralized system that connects all the components via long wires, the savings are remarkable. As Rivian chief executive RJ Scaringe posted on X: “The R2 harness improves massively over the R1 Gen 2 harness. Building on the backbone of our network architecture and zonal ECUs, we focused on ease of install in the plant and overall simplification through integrated design — less wires, less clips and far fewer splices!”

Legacy automakers, meanwhile, are racing to catch up. Even those that have built decent-selling quality EVs to date have not come close to matching the software sophistication of Tesla and Rivian. But they have begun to see the light — not just about fancy iPads in the cockpit, but also about how the software-defined vehicle can help them to run their factories in a simpler and cheaper way.

How those companies approach the software-defined car will define them in the years to come. By 2028, GM hopes to have finished its next-gen software platform that “will unite every major system from propulsion to infotainment and safety on a single, high-speed compute core,” according to Barra. The hope is that this approach not only cuts down on wiring and simplifies manufacturing, but also makes Chevys and Cadillacs more easily updatable and better-equipped for the self-driving future.

In that sense, it’s not about the wires. It’s about all the trends that have come to dominate electric vehicles — affordability, functionality, and autonomy — colliding head-on.

Europeans have been “snow farming” for ages. Now the U.S. is finally starting to catch on.

February 2015 was the snowiest month in Boston’s history. Over 28 days, the city received a debilitating 64.8 inches of snow; plows ran around the clock, eventually covering a distance equivalent to “almost 12 trips around the Equator.” Much of that plowed snow ended up in the city’s Seaport District, piled into a massive 75-foot-tall mountain that didn’t melt until July.

The Seaport District slush pile was one of 11 such “snow farms” established around Boston that winter, a cutesy term for a place that is essentially a dumpsite for snow plows. But though Bostonians reviled the pile — “Our nightmare is finally over!” the Massachusetts governor tweeted once it melted, an event that occasioned multiple headlines — the science behind snow farming might be the key to the continuation of the Winter Olympics in a warming world.

The number of cities capable of hosting the Winter Games is shrinking due to climate change. Of 93 currently viable host locations, only 52 will still have reliable winter conditions by the 2050s, researchers found back in 2024. In fact, over the 70 years since Cortina d’Ampezzo first hosted the Olympic Games in 1956, February temperatures in the Dolomites have warmed by 6.4 degrees Fahrenheit, according to Climate Central, a nonprofit climate research and communications group. Italian organizers are expected to produce more than 3 million cubic yards of artificial snow this year to make up for Mother Nature’s shortfall.

But just a few miles down the road from Bormio — the Olympic venue for the men’s Alpine skiing events as well as the debut of ski mountaineering next week — is the satellite venue of Santa Caterina di Valfurva, which hasn’t struggled nearly as much this year when it comes to usable snow. That’s because it is one of several European ski areas that have begun using snow farming to their advantage.

Like Ruka in Finland and Saas-Fee in Switzerland, Santa Caterina plows its snow each spring into what is essentially a more intentional version of the Great Boston Snow Pile. Using patented tarps and siding created by a Finnish company called Snow Secure, the facilities cover the snow … and then wait. As spring turns to summer, the pile shrinks, not because it’s melting but because it’s becoming denser, reducing the air between the individual snowflakes. In combination with the pile’s reduced surface area, this makes the snow cold and insulated enough that not even a sunny day will cause significant melt-off. (Neil DeGrasse Tyson once likened the phenomenon to trying to cook an entire potato with a lighter; successfully raising the inner temperature of a dense snowball, much less a gigantic snow pile, requires more heat.)

Shockingly little snow melts during storage. Snow Secure reports a melt rate of 8% to 20% on piles that can be 50,000 cubic meters in size, or the equivalent of about 20 Olympic swimming pools. When autumn eventually returns, ski areas can uncover their piles of farmed snow and spread it across a desired slope or trail using snowcats, specialized groomers that break up and evenly distribute the surface. For Santa Caterina, the goal was to store enough to make a nearly 2-mile-long cross-country trail — no need to wait for the first significant snowfall of the season, which creeps later and later every year.

“In many places, November used to be more like a winter month,” Antti Lauslahti, the CEO of Snow Secure, told me. “Now it’s more like a late-autumn month; it’s quite warm and unpredictable. Having that extra few weeks is significant. When you cannot open by Thanksgiving or Christmas, you can lose 20% to 30% of the annual turnover.”

Though the concept of snow farming is not new — Lauslahti told me the idea stems from the Finnish tradition of storing snow over the summer beneath wood chips, once a cheap byproduct of the local logging industry — the company's polystyrene mat technology, which helps to reduce summer melt, is. Now that the technique is patented, Snow Secure has begun expanding into North America with a small team. The venture could prove lucrative: Researchers expect that by the end of the century, as many as 80% of the downhill ski areas in the U.S. will be forced to wait until after Christmas to open, potentially resulting in economic losses of up to $2 billion.

While there have been a few early adopters of snow farming in Wisconsin, Utah, and Idaho, the number of ski areas in the United States using the technique remains surprisingly low, especially given its many other upsides. In the States, the most common snow management system is the creation of artificial snow, which is typically water- and energy-intensive. Snow farming not only avoids those costs — which can also have large environmental tolls, particularly in the water-strapped West — but the super-dense snow farming produces is “really ideal” for something like the Race Centre at Canada’s Sun Peaks Resort, where top athletes train. Downhill racers “want that packed, harder, faster snow,” Christina Antoniak, the area’s director of brand and communications, told me of the success of the inaugural season of snow farming at Sun Peaks. “That’s exactly what stored snow produced for that facility.”

The returns are greatest for small ski areas, which are also the most vulnerable to climate change. While the technology is an investment — Antoniak ballparked that Sun Peaks spent around $185,000 on Snow Secure’s siding — the money goes further at a smaller park. At somewhere like Park City Mountain in Utah, stored snow would cover only a small portion of the area’s 140 miles of skiable routes. But it can make a major difference for an area down the road like the Soldier Hollow Nordic Center, which has a more modest 20 miles of cross-country trails.

In fact, the 2025-2026 winter season will be the Nordic Center’s first using Snow Secure’s technology. Luke Bodensteiner, the area’s general manager and chief of sport, told me that alpine ski areas are “all very curious to see how our project goes. There is a lot of attention on what we do, and if it works out satisfactorily, we might see them move into it.”

Ensuring a reliable start to the ski season is no small thing for a local economy; jobs and travel plans rely on an area being open when it says it will be. But for the Soldier Hollow Nordic Center, the stakes are even higher: The area is one of the planned host venues of the 2034 Salt Lake City Winter Games. “Based on historical weather patterns, our goal is to be able to make all the snow that we need for the entire Olympic trail system in two weeks,” Bodensteiner said, adding, “We envision having four or five of these snow piles around the venue in the summer before the Olympic Games, just to guarantee — in a worst case scenario — that we’ve got snow on the venue.”

Antoniak, at Canada’s Sun Peaks, also told me that their area has been a bit of a “guinea pig” when it comes to snow farming. “A lot of ski areas have had their eyes on Sun Peaks and how [snow farming is] working here,” she told me. “And we’re happy to have those conversations with them, because this is something that gives the entire industry some more resiliency.”

Of course, the physics behind snow farming has a downside, too. The same science saving winter sports is also why that giant, dirty pile of plowed snow outside your building isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Current conditions: A train of three storms is set to pummel Southern California with flooding rain and up to 9 inches mountain snow • Cyclone Gezani just killed at least four people in Mozambique after leaving close to 60 dead in Madagascar • Temperatures in the southern Indian state of Kerala are on track to eclipse 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

What a difference two years makes. In April 2024, New York announced plans to open a fifth offshore wind solicitation, this time with a faster timeline and $200 million from the state to support the establishment of a turbine supply chain. Seven months later, at least four developers, including Germany’s RWE and the Danish wind giant Orsted, submitted bids. But as the Trump administration launched a war against offshore wind, developers withdrew their bids. On Friday, Albany formally canceled the auction. In a statement, the state government said the reversal was due to “federal actions disrupting the offshore wind market and instilling significant uncertainty into offshore wind project development.” That doesn’t mean offshore wind is kaput. As I wrote last week, Orsted’s projects are back on track after its most recent court victory against the White House’s stop-work orders. Equinor's Empire Wind, as Heatmap’s Jael Holzman wrote last month, is cruising to completion. If numbers developers shared with Canary Media are to be believed, the few offshore wind turbines already spinning on the East Coast actually churned out power more than half the time during the recent cold snap, reaching capacity factors typically associated with natural gas plants. That would be a big success. But that success may need the political winds to shift before it can be translated into more projects.

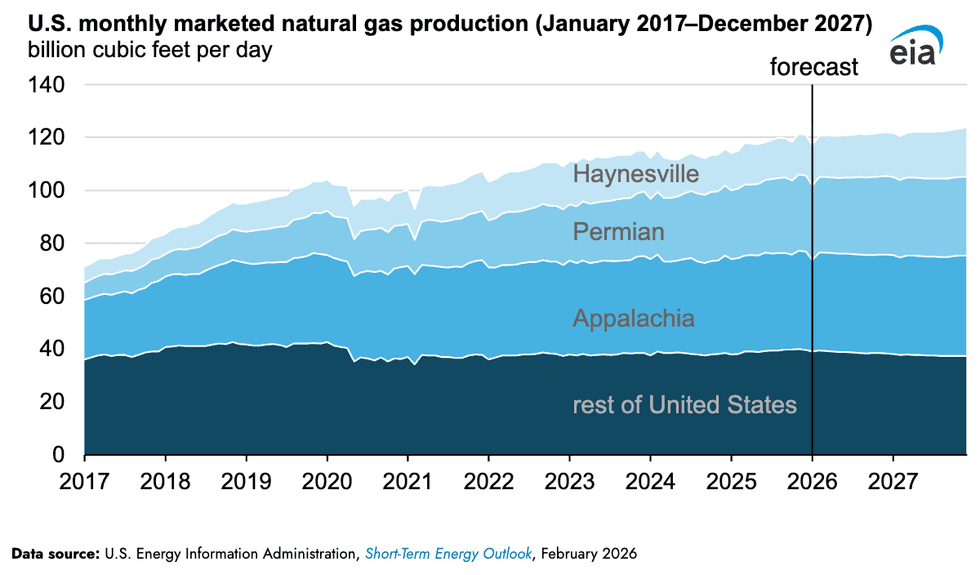

President Donald Trump’s “drill, baby, drill” isn’t moving American oil extractors, whose output is set to contract this year amid a global glut keeping prices low. But production of natural gas is set to hit a record high in 2026, and continue upward next year. The Energy Information Administration’s latest short-term energy outlook expects natural gas production to surge 2% this year to 120.8 billion cubic feet per day, from 118 billion in 2025 — then surge again next year to 122.3 billion cubic feet. Roughly 69% of the increased output is set to come from Appalachia, Louisiana’s Haynesville area, and the Texas Permian regions. Still, a lot of that gas is flowing to liquified natural gas exports, which Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin explained could raise prices.

The U.S. nuclear industry has yet to prove that microreactors can pencil out without the economies of scale that a big traditional reactor achieves. But two of the leading contenders in the race to commercialize the technology just crossed major milestones. On Friday, Amazon-backed X-energy received a license from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to begin commercial production of reactor fuel high-assay low-enriched uranium, the rare but potent material that’s enriched up to four times higher than traditional reactor fuel. Due to its higher enrichment levels, HALEU, pronounced HAY-loo, requires facilities rated to the NRC’s Category II levels. While the U.S. has Category I facilities that handle low-enriched uranium and Category III facilities that manage the high-grade stuff made for the military, the country has not had a Category II site in operation. Once completed, the X-energy facility will be the first, in addition to being the first new commercial fuel producer licensed by the NRC in more than half a century.

On Sunday, the U.S. government airlifted a reactor for the first time. The Department of Defense transported one of Valar Atomics’ 5-megawatt microreactors via a C-17 from March Air Reserve Base in California to Hill Air Force Base in Utah. From there, the California-based startup’s reactor will go to the Utah Rafael Energy Lab in Orangeville, Utah, for testing. In a series of posts on X, Isaiah Taylor, Valar’s founder, called the event “a groundbreaking unlock for the American warfighters.” His company’s reactor, he said, “can power 5,000 homes or sustain a brigade-scale” forward operating base.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

After years of attempting to sort out new allocations from the dwindling Colorado River, negotiators from states and the federal government disbanded Friday without a plan for supplying the 40 million people who depend on its waters. Upper-basin states Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico have so far resisted cutting water usage when lower-basin states California, Arizona, and Nevada are, as The Guardian put it, “responsible for creating the deficit” between supply and demand. But the lower-basin states said they had already agreed to substantial cuts and wanted the northern states to share in the burden. The disagreement has created an impasse for months; negotiators blew through deadlines in November and January to come up with a solution. Calling for “unprecedented cuts” that he himself described as “unbelievably harsh,” Brad Udall, senior water and climate research scientist at Colorado State University’s Colorado Water Center, said: “Mother Nature is not going to bail us out.”

In a statement Friday, Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum described “negotiations efforts” as “productive” and said his agency would step in to provide guidelines to the states by October.

Europe’s “regulatory rigidity risks undermining the momentum of the hydrogen economy. That, at least, is the assessment of French President Emmanuel Macron, whose government has pumped tens of billions of euros into the clean-burning fuel and promoted the concept of “pink hydrogen” made with nuclear electricity as the solution that will make energy technology take off. Speaking at what Hydrogen Insight called “a high-level gathering of CEOs and European political leaders,” Macron, who is term-limited in next year’s presidential election, said European rules are “a crazy thing.” Green hydrogen, the version of the fuel made with renewable electricity, remains dogged by high prices that the chief executive of the Spanish oil company Repsol said recently will only come down once electricity rates decrease. The Dutch government, meanwhile, just announced plans to pump 8 billion euros, roughly $9.4 billion, into green hydrogen.

Kazakhstan is bringing back its tigers. The vast Central Asian nation’s tiger reintroduction program achieved record results in reforesting an area across the Ili River Delta and Southern Balkhash region, planting more than 37,000 seedlings and cuttings on an area spanning nearly 24 acres. The government planted roughly 30,000 narrow-leaf oleaster seedlings, 5,000 willow cuttings, and about 2,000 turanga trees, once called a “relic” of the Kazakh desert. Once the forests come back, the government plans to eventually reintroduce tigers, which died out in the 1950s.