You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

New data provided exclusively to Heatmap shows just how complicated it is to get money where it needs to go.

By the numbers, a new federal program designed to give low-income communities access to renewable energy looks like a smashing success. According to data provided exclusively to Heatmap, in its first year, the Low-Income Communities Bonus Credit Program steered nearly 50,000 solar projects to low-income communities and tribal lands, which are together expected to produce more than $270 million in annual energy savings.

But those topline numbers don’t say anything about who will actually see the savings, or how much the projects will benefit households that have historically been left behind. In reality, the majority of the projects — about 98% — were allocated funding simply for being located in low-income communities, with no hard requirement to deliver energy or financial savings to low-income residents.

A closer look at the data reveals a more complicated success story. While the program did make some clear strides in bridging the solar inequality gap, other factors — including the language in the law that created it — are also holding it back.

The Low-Income Communities Bonus Credit Program came out of the Inflation Reduction Act in August 2022. Though the goal is to increase solar access for low-income households, it’s not actually a tax credit for low income households. It’s for small wind and solar developers — and beginning in 2025, developers of other types of clean energy — whose projects meet certain criteria.

The law caps the total amount of energy the program can support at 1.8 gigawatts per year, and developers have to apply and get their project approved in order to claim funds. To be eligible, a project must produce less than 5 megawatts of power and fall under one of four categories: It must be located in a low-income community, be built on Indian land, be part of an affordable housing development, or distribute at least half its power (and guaranteed bill savings) to low-income households. The first two categories qualify for a 10% credit; the second two, which stipulate that at least some financial benefits go to low-income residents, qualify for 20%. In both cases, the credit can be stacked on top of the baseline 30% tax credit for clean energy projects that meet labor standards, meaning it could slash the cost of building a small solar or wind farm in half.

Each of these provisions has the potential to address at least some of the barriers disadvantaged communities face in accessing clean energy. Low-income homeowners may not have the money for a down payment for rooftop solar or the credit to find financing, for instance. But by giving developers a tax credit for projects located in low-income communities, solar leasing programs, in which homeowners lease panels from a third party in exchange for energy bill savings, now have an incentive to expand into these neighborhoods, and potentially offer lower lease rates. The program helped fund nearly 48,000 residential solar projects in the first year.

Tribal lands, meanwhile, account for more than 5% of solar generation potential in the U.S., but are still a largely untapped resource, for reasons including lack of representation in utility regulatory processes, complex land ownership structures, and limited tribal staff capacity. The program gives outside developers additional incentive to work through the challenges, and it also earmarks funds for tribe-owned development. Crucially, the IRA also opened the door for tribes, as well as other tax-exempt entities, to utilize clean energy incentives and receive a direct payment equal to the tax credits. The program supported 96 solar projects on tribal lands in the first year.

The third category attempts to overcome the famous “split incentive” problem for low-income renters whose landlords have little reason to spend money on a solar project that primarily benefits tenants. The program helped finance 805 solar projects on low-income residential buildings, where the developers are required to distribute at least 50% of the energy savings equitably among tenants.

Lastly, while renters in some states can subscribe to community solar projects, which offer utility bill credits in exchange for a small subscription fee, the subscriptions can be scooped up by wealthier customers if there’s no low-income requirement. The program sponsored 319 community solar projects where at least half the capacity had to go to low-income residents and offer at least 20% off their bills.

U.S. Deputy Secretary of the Treasury Wally Adeyemo declared the program a success. “These investments are already lowering costs, protecting families from energy price spikes, and creating new opportunities in our clean energy future,” he said.

Despite overwhelming demand during the four-month application period, however, the program ended up with capacity to spare. Although applications totaled more than 7 gigawatts, ultimately, the Department approved just over 49,000 projects equal to about 1.4 gigawatts, or roughly enough to power 200,000 average households. All of it was solar.

The gap between applications and awarded projects has to do with the program’s design. The Treasury divided the 1.8 gigawatt cap between the four categories, setting maximum amounts that could be awarded for each one. Within the four categories, the awards were further divided, with half set aside for applicants that met additional ownership or geographic criteria, such as tribal-owned companies, tax-exempt entities, or projects sited in areas with especially high energy costs relative to incomes.

For example, 200 megawatts were earmarked for Indian lands, with half reserved for applicants meeting those additional criteria, but only 40 megawatts were awarded. The fourth category, meanwhile, which was designed to encourage community solar development, was oversubscribed.

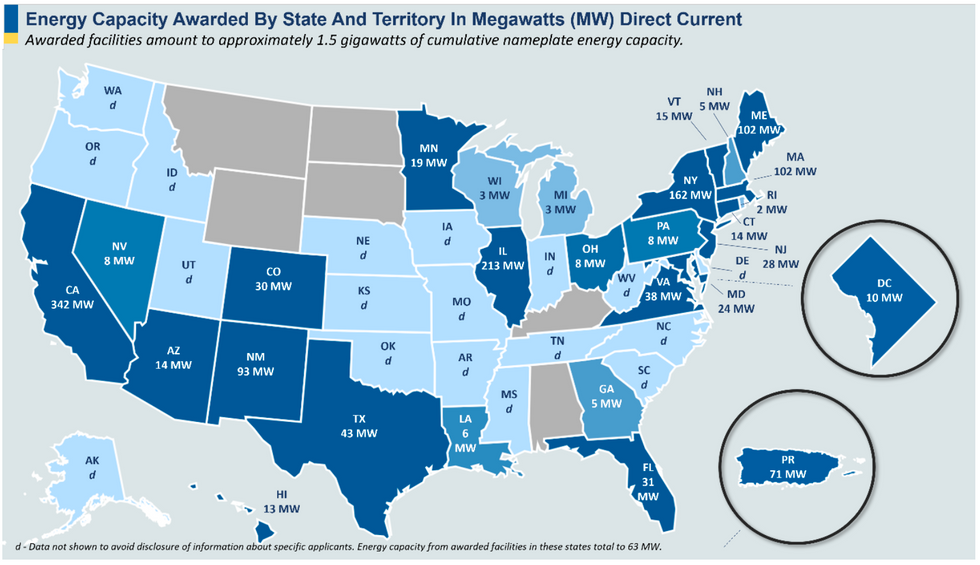

Since tax data is confidential, the Treasury Department could not share much detail about these projects, including where, exactly, they were, who developed them, or who will benefit from them. A map overview shows a concentration of awards across the sunbelt, with Illinois, New York, Maine, Massachusetts, and Puerto Rico also seeing a lot of uptake.

I reached out to more than a dozen nonprofits, tribal organizations, and other groups who advocate for or develop clean energy projects benefiting low-income communities to find examples of what the program was actually funding. The first person I was connected with was Richard Best, the director of capital projects and planning for Seattle Public Schools, who got a 10% tax credit for solar arrays on two new schools under construction in low-income neighborhoods. While the school system already planned to put solar on these schools, Best said the tax credits helped offset increased construction costs due to supply chain interruptions, preventing them from having to make compromises on design elements like classroom size.

“It's not insignificant,” he told me. “The solar array at Rainier Beach High School is in excess of a million dollars — just the rooftop solar array. That's $400,000 [in tax credits]. So these are significant dollars that we're receiving, and we're very appreciative.”

Jody Lincoln, an affordable housing development officer for the nonprofit ACTION-Housing in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, got a 10% tax credit to add solar to a former YMCA that the group recently converted to a 74-unit apartment building. The single room occupancy rental units serve men who are coming out of homelessness or incarceration. Lincoln told me the building operates “in the gray,” and that any cost saving measures they can make, including the energy savings from the solar array, enable it to continue to operate as affordable housing. When I asked if they could have built the solar project without access to the IRA’s tax credits, she didn’t hesitate: “No.”

These two examples show the program has potential to deliver benefits to low-income communities, even in cases where the energy savings aren’t going directly to low-income residents.

I also spoke with Alexandra Wyatt, the managing policy director and counsel at the nonprofit solar company Grid Alternatives. She told me Grid partnered with for-profit solar developers, such as the national solar company SunRun, who were approved for the tax credit bonus for rooftop solar lease projects on low-income single-family homes. In these cases, Grid helped pull together other sources of funding like state incentives for projects in disadvantaged communities to pre-pay the leases so that the homeowners could more fully benefit from the energy bill savings.

It’s unlikely that all of the nearly 48,000 residential rooftop solar projects in low-income communities that were approved for the credit in the first year had such virtuous outcomes. It’s also possible that projects installed on wealthier homeowners’ roofs in gentrifying neighborhoods were subsidized. In an email to me, a Treasury spokesperson said the Department recognizes that “simply being in a low-income community does not mean low-income households are being served,” and that it was required by statute to include this category. It was still the agency’s decision, however, to allocate such a large portion of the awards, 700 megawatts, to this category — a decision that some public comments on the program disagreed with.

Wyatt applauded the Treasury and the Department of Energy, which oversees the application process, for doing “an admirable job on a tight timeframe with a challenging program design handed to them by Congress.” She’s especially frustrated by the 1.8 gigawatt cap, which none of the other renewable energy tax credits have, and which changes it into a competitive grant that’s more burdensome both for developers and for the agencies. It adds an element of uncertainty to project finance, she said, since developers have to wait to see if their application for the credit was approved.

Wendolyn Holland, the senior advisor for policy, tax and government relations at the Alliance for Tribal Clean Energy told me there was tons of interest among indigenous communities and tribal clean energy developers in taking advantage of the IRA programs, but it wasn’t really happening. Holland cited challenges for tribes reaching the stage of “commercial readiness” required to apply for federal funding. Tribal developers have also said they are limited by the lack of transmission on tribal lands. When I asked the Treasury about the paltry number of projects on Indian Lands, a spokesperson said it was not for lack of trying. The Department and other federal agencies have conducted webinars and other forms of outreach, they said, through which they’ve heard that many tribes are struggling to access capital for energy projects, and that development on Indian lands has “unique challenges due to the history of allotment of Indian lands and status of some land as federal trust land.”

Holland is optimistic that things will change — in December, Biden issued an executive order committing to making it easier for tribes to access federal funding. The Alliance also recently petitioned the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to address barriers for tribal energy development in its new rules that are supposed to get more transmission built.

The unallocated capacity from 2023 was carried over to the next year’s round of funding, so it wasn’t lost. But a dashboard tracking the second year of the program looks like it's following a similar pattern. While the community solar-oriented category, which was increased to allow for 900 megawatts, is nearly filled up, the tribal Lands category, which kept its 200 megawatt cap, has received applications to develop less than a sixth of that.

Wyatt said that so far, she does think the bonus credit has been successful in spurring good projects that might not otherwise have happened. Still, it will probably take a few years before it will be possible to assess how well it’s working. The good news is, as long as it doesn’t get repealed, the program could run for up to eight more years, leaving plenty of time to improve things. It’s already set to change in one key way. Beginning in 2025, it becomes tech-neutral, meaning that developers of small hydroelectric, geothermal heating or power, or nuclear projects, will be able to apply. (When asked why no wind projects were approved to date, a spokesperson for the Treasury said taxpayer privacy rules meant it couldn’t comment on applications, but they added that wind projects tend to be larger than 5 megawatts and take longer to develop.)

One thing is for sure, despite the heavy administrative burden of screening tens of thousands of applications, the agencies involved are clearly committed to implementing the program.

“I’m definitely pleased that they managed to get the program up and running as quickly as they did,” Wyatt told me. “I mean, it's kind of lightning speed for the IRS.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

A new report from the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy has some exciting data for anyone attempting to retrofit a multifamily building.

By now there’s plenty of evidence showing why heat pumps are such a promising solution for getting buildings off fossil fuels. But most of that research has focused on single-family homes. Larger apartment buildings with steam or hot water heating systems — i.e. most of the apartment buildings in the Northeast — are more difficult and expensive to retrofit.

A new report from the nonprofit American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, however, assesses a handful of new technologies designed to make that transition easier and finds they have the potential to significantly lower the cost of decarbonizing large buildings.

“Several new options make decarbonizing existing commercial and multifamily buildings much more feasible than a few years ago,” Steven Nadel, ACEEE’s executive director and one of the authors, told me. “The best option may vary from building to building, but there are some exciting new options.”

To date, big, multifamily buildings have generally had two flavors of heat pumps to consider. They can install a large central heat pump system that delivers heating and cooling throughout the structure, or they can go with a series of “mini-split” systems designed to serve each apartment individually. (Yes, there are geothermal heat pumps, too, but those are often even more expensive and complicated to install, especially in urban areas.)

While these options have proven to work, they often require a fair amount of construction work, including upgrading electrical systems, mounting equipment on interior and exterior walls, and running new refrigerant lines throughout the building. That means they cost a lot more than a simple boiler replacement, and that the retrofit process can be disruptive to residents.

In 2022, the New York City Housing Authority launched a contest to try and solve these problems by challenging manufacturers to develop heat pumps that can sit in a window just like an air conditioner. New designs from the two winners, Gradient Comfort and Midea, are just starting to come to market. But another emerging solution, central air-to-water heat pumps, also presents an appealing alternative. These systems avoid major construction because they can integrate with existing radiators or baseboard heaters in buildings that currently use hot water boilers. Instead of burning natural gas or oil to produce hot water, the heat pump warms the water using electricity.

The ACEEE report takes the cost and performance data for these emerging solutions and compares it to results from mini-splits, central heat pumps, geothermal heat pumps, packaged terminal heat pumps — all-in-one devices that sit inside a sleeve in the wall, commonly used in hotels — and traditional boilers fed by biogas or biodiesel.

While data on the newer technologies is limited, so far the results are extremely promising. The report found that window heat pumps are the most cost-effective of the bunch to fully decarbonize large apartment buildings, with an average installation cost of $9,300 per apartment. That’s significantly higher than the estimated $1,200 per apartment cost of a new boiler, but much lower than the $14,000 to $20,000 per apartment price tag of the other heat pump variations, although air-to-water heat pumps came in second. The report also found that window heat pumps could turn out to be the cheapest to operate, with a life cycle cost of about $14,500, compared to $22,000 to $30,000 for boilers using biodiesel or biogas or other heat pump options.

As someone who has followed this industry for several years with a keen interest in new solutions for boiler-heated buildings in the Northeast — where I grew up and currently reside — I was especially wowed by how well the new window heat pumps have performed. New York City installed units from both Midea and Gradient in 24 public housing apartments, placing one in each bedroom and living room, and monitored the results for a full heating season.

Preliminary data shows the units performed swimmingly on every metric.

On ease of installation: It took a total of eight days for maintenance workers to install the units in all 24 apartments, compared to about 10 days per apartment when the Housing Authority put split heat pump systems in another building.

On performance: During the winter, while other apartments in the building were baking in 90-degree Fahrenheit heat from the steam system, the window unit-heated apartments maintained a comfortable 75 to 80 degree range, even as outdoor temperatures dropped to as low as 20 degrees.

On energy and cost: The window unit-heated apartments used a whopping 87% less energy than the rest of the building’s steam-heated apartments did, cutting energy costs per household in half.

On customer satisfaction: A survey of 72 residents returned overwhelmingly positive feedback, with 93% reporting that the temperature was “just right” and 100% reporting they were either “neutral” or “satisfied” with the new units.

The Housing Authority found that the units also lowered energy used for cooling in peak summer since they were more efficient than the older window ACs residents had been using. Next, the agency plans to expand the pilot to two full buildings before deploying the units across its portfolio. The pilot was so successful that utilities in Massachusetts, Vermont, and elsewhere are purchasing units to do their own testing.

The ACEEE report looked at a handful of air-to-water heat pump projects in New York and Massachusetts, as well, only two of which have been completed. The average installation cost per apartment was around $13,500, with each of the buildings retaining a natural gas boiler as a backup, but none had published performance data yet.

Air-to-water heat pumps have only recently come to market in the U.S. after having taken off in Europe, and they don’t yet fit seamlessly into the housing stock here. Existing technology can only heat water to 130 to 140 degrees, which is hot enough for the more efficient hot water radiators common in Europe but too cold for the U.S. market, where hot water systems are designed to carry 160- to 180-degree water, or even steam.

These heat pumps can still work in U.S. buildings, but they require either new radiators to be installed or supplemental heat from a conventional boiler or electric resistance unit. The other downside to an air-to-water system is that it can’t provide cooling unless the building is already equipped with compatible air conditioning units.

One strength of these systems over the window units, however, is that they don’t push costs onto tenants in buildings where the landlord has historically paid for heat. They also may be cheaper to operate than more traditional heat pump options, although data is still extremely limited and depends on the use of supplemental heat.

It’s probably too soon to draw any major conclusions about air-to-water systems, anyway, because new, potentially more effective options are on the way. In 2023, New York State launched a contest challenging manufacturers to develop new decarbonized heating solutions for large buildings. Among the finalists announced last year, six companies were developing heat pumps that could generate higher-temperature hot water and/or steam. One of them is now installing its first demonstration system in an apartment building in Harlem, and two others have similar demonstrations in the works.

The ACEEE report also mentions a few other promising new heat pump formats, such as an all-in-one wall-mounted heat pump from Italian company Ephoca. It’s similar to the window heat pump in that it’s contained in a single device rather than split into an indoor and outdoor unit, so it doesn’t require mounting anything to the outside of the building or worrying about refrigerant lines, although it does require drilling two six-inch holes in the wall for vents. These may be a good option for those whose windows won’t accommodate a window heat pump or who don’t like the aesthetics. New York State is also funding product development for better packaged terminal heat pumps that could slot into wall cavities occupied by less-efficient packaged terminal air conditioners and heat pumps today.

Gradient and Midea are not yet selling their cold-climate window heat pumps to the general public. Gradient brought a version of its technology for more moderate climates to market in 2023, which was only suitable for heating at outdoor temperatures of 40 degrees and higher. But the company has discontinued that model and is focusing on an “all-weather” version designed for cold climates, which is the one that has been installed in the New York City apartments. Neither company responded to my inquiry about when their heat pumps would be available to consumers.

One big takeaway is that even the new school heat pumps designed to be easier and cheaper to install have higher capital costs than buying a boiler and air conditioners — a stubborn facet of many climate solutions, even when they save money in the long run. Canary Media previously reported that the Gradient product would start at $3,800 per unit and the Midea at $3,000. Experts expect the cost to come down as adoption and demand pick up, but the ACEEE report recommends that states develop incentives and financing to help with up-front costs.

“These are not just going to happen on their own. We do need some policy support for them,” Nadel said. In addition to incentives and building decarbonization standards, Nadel raised the idea of discounted electric rates for heat pump users, an idea that has started to gain traction among climate advocates that a few utilities have piloted.

“To oversimplify,” Nadel said, “in many jurisdictions, heat pumps subsidize other customers, and that probably needs to change if this is going to be viable.”

Current conditions: Two people are missing after torrential rains in Catalonia • The daily high will be over 115 degrees Fahrenheit every day this week in Baghdad, Iraq • The search for victims of the Texas floods is paused due to a new round of rains and flooding in the Hill Country.

Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem defended the Federal Emergency Management Agency after The New York Times reported it failed to answer nearly two-thirds of the calls placed to its disaster assistance line by victims of the Central Texas floods. Speaking on NBC’s Meet the Press on Sunday, Noem repudiated reports by the Times and Reuters that her requirement that she personally approve expenses over $100,000, as well as the deployment of other critical resources, created bottlenecks during the crucial hours after the floodwaters receded. “Those claims are absolutely false,” she said.

Noem additionally denied reports that FEMA’s failure to renew the contracts of call-center contractors created a slowdown at the agency. Per the Times’ reporting, FEMA allowed its call center contract extension to expire on the night of July 5, in the midst of the unfolding disaster. During the day on July 5, FEMA answered the calls of 99.7% of survivors seeking one-time assistance for their immediate needs, the Times’ reporting shows; after FEMA failed to renew the contracts and hundreds of contractors were fired, the answer rate dropped to just 35.8% on July 6, and 15.9% on July 7. “Those contracts were in place, no employees were off of work,” Noem told Meet the Press. (Reuters reports that an internal FEMA document shows Noem approved the call center contracts as of July 10.)

At least 120 people died in the flash floods in Texas’ Hill Country over the Fourth of July weekend, with more than 160 people still missing. FEMA has fired or bought out at least 2,000 full-time employees since the start of the year, though since the floods, the Trump administration has reframed its push to “abolish” FEMA as “rebranding” FEMA, instead.

The Trump administration last week fired the final handful of employees who worked at the Office of Global Change, the division of the State Department that focused on global climate negotiations. Per The Washington Post, the employees were the final group at the department working on issues of international climate policy, and were part of bigger cuts to the agency that will see nearly 3,000 staffers out of work. “The Department is undertaking a significant and historic reorganization to better align our workforce activities and programs with the America First foreign policy priorities,” the State Department told the Post in a statement about the shuttering of the office.

The historic Grand Canyon Lodge burned down in the nearly 6,000-acre Dragon Bravo Fire in Arizona over the weekend. The rustic lodge, located on the Canyon’s remote North Rim, had stood since 1937, when it was rebuilt after a kitchen fire, and was the only hotel located inside the boundaries of the national park.

Arizona Governor Katie Hobbs called for an investigation into the National Park Service’s handling of the fire, which destroyed an additional 50 to 80 structures on the park’s North Rim. “An incident of this magnitude demands intense oversight and scrutiny into the federal government’s emergency response,” she said, adding that “Arizonans deserve answers for how this fire was allowed to decimate the Grand Canyon National Park.” The Dragon Bravo Fire is one of two wildfires burning on the park’s north side and began after a lightning strike on July 4. The famous Phantom Ranch, located inside the canyon, and popular Bright Angel Trail and Havasupai Gardens, were also closed to hikers as of Sunday due to the fires.

Late last week, the local government of Nantucket reached a settlement with GE Vernova for $10.5 million to compensate for the tourism and business losses that resulted from the July 2024 turbine failure at Vineyard Wind 1. The town will use the money to establish a Community Claims Fund to provide compensation to affected parties.

The incident involved a 350-foot blade from a GE Vernova turbine that split off and fell into the water during construction of Vineyard Wind. Debris washed up onshore, temporarily closing some of the Massachusetts island’s iconic beaches during the height of tourist season. “The backlash was swift,” my colleague Emily Pontecorvo reported at the time. “Nantucket residents immediately wrote to Nantucket’s Select Board to ask the town to stop the construction of any additional offshore wind turbines.” Though significant errors like blade failures are incredibly rare, as my colleague Jael Holzman has also reported, the disaster could not have come at a worse time for Vineyard Wind, which subsequently saw its expansion efforts stymied by the Trump administration.

Nineteen states and the territory of Guam moved last week to intervene in a May lawsuit claiming the Trump administration has violated young people’s right to good health and a stable environment. The original complaint was filed in May by 22 plaintiffs represented by Our Children’s Trust — the same Oregon group that brought Held v. Montana, which successfully argued that the state violated young people’s constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment, as well as the groundbreaking climate case Juliana v. United States, which the Supreme Court declined to hear this spring.

In the new Montana-led move, the coalition of states represented by their respective attorneys general is seeking to join the lawsuit as defendants. Per Our Children’s Trust, the plaintiffs will file a formal response to the motion to intervene in the coming weeks.

More than half of all the soybean oil produced in the United States next year will be used to make biofuel, according to a new outlook by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect the current state of the youth climate lawsuit.

The multi-faceted investment is defense-oriented, but could also support domestic clean energy.

MP Materials is the national champion of American rare earths, and now the federal government is taking a stake.

The complex deal, announced Thursday, involves the federal government acting as a guaranteed purchaser of MP Materials’ output, a lender, and also an investor in the company. In addition, the Department of Defense agreed to a price floor for neodymium-praseodymium products of $110 per kilogram, about $50 above its current spot price.

MP Materials owns a rare earths mine and processing facility near the California-Nevada border on the edges of the Mojave National Preserve. It claims to be “the largest producer of rare earth materials in the Western Hemisphere,” with “the only rare earth mining and processing site of scale in North America.”

As part of the deal, the company will build a “10X Facility” to produce magnets, which the DOD has guaranteed will be able to sell 100% of its output to some combination of the Pentagon and commercial customers. The DOD is also kicking in $150 million worth of financing for MP Materials’ existing processing efforts in California, alongside $1 billion from Wall Street — specifically JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs — for the new magnet facility. The company described the deal in total as “a multi-billion-dollar commitment to accelerate American rare earth supply chain independence.”

Finally, the DOD will buy $400 million worth of newly issued stock in MP Materials, giving it a stake in the future production that it’s also underwriting.

Between the equity investment, the lending, and the guaranteed purchasing, the Pentagon, and by extension the federal government, has taken on considerable financial risk in casting its lot with a company whose primary asset’s previous owner went bankrupt a decade ago. But at least so far, Wall Street is happy with the deal: MP Materials’ market capitalization soared to over $7 billion on Thursday after its share price jumped over 40%, from a market capitalization of around $5 billion on Wednesday and the company is valued at around $7.5 billion as of Friday afternoon.

Despite the risk, former Biden administration officials told me they would have loved to make a deal like this.

When I asked Alex Jacquez, who worked on industrial policy for the National Economic Council in the Biden White House, whether he wished he could’ve overseen something like the DOD deal with MP Materials, he replied, “100%.” I put the same question to Ashley Zumwalt-Forbes, a former Department of Energy official who is now an investor; she said, “Absolutely.”

Rare earths and critical minerals were of intense interest to the Biden administration because of their use in renewable energy and energy storage. Magnets made with neodymium-praseodymium oxide are used in the electric motors found in EVs and wind turbines, as well as for various applications in the defense industry.

MP Materials will likely have to continue to rely on both sets of customers. Building up a real domestic market for the China-dominated industry will likely require both sets of buyers. According to a Commerce Department report issued in 2022, “despite their importance to national security, defense demand for … magnets is only a small portion of overall demand and insufficient to support an economically viable domestic industry.”

The Biden administration previously awarded MP Materials $58.5 million in 2024 through the Inflation Reduction Act’s 48C Advanced Energy Project tax credit to support the construction of a magnet facility in Fort Worth. While the deal did not come with the price guarantees and advanced commitment to purchase the facility’s output of the new agreement, GM agreed to come on as an initial buyer.

Matt Sloustcher, an MP Materials spokesperson, confirmed to me that the Texas magnet facility is on track to be fully up and running by the end of this year, and that other electric vehicle manufacturers could be customers of the new facility announced on Thursday.

At the time MP Materials received that tax credit award, the federal government was putting immense resources behind electric vehicles, which bolstered the overall supply supply chain and specifically demand for components like magnets. That support is now being slashed, however, thanks to the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which will cancel consumer-side subsidies for electric vehicle purchases.

While the Biden tax credit deal and the DOD investment have different emphases, they both follow on years of bipartisan support for MP Materials. In 2020, the DOD used its authority under the Defense Production Act to award almost $10 million to MP Materials to support its investments in mineral refining. At the time, the company had been ailing in part due to retaliatory tariffs from China, cutting off the main market for its rare earths. The company was shipping its mined product to China to be refined, processed, and then used as a component in manufacturing.

“Currently, the Company sells the vast majority of its rare earth concentrate to Shenghe Resources,” MP Materials the company said in its 2024 annual report, referring to a Chinese rare earths company.

The Biden administration continued and deepened the federal government’s relationship with MP Materials, this time complementing the defense investments with climate-related projects. In 2022, the DOD awarded a contract worth $35 million to MP Materials for its processing project in order to “enable integration of [heavy rare earth elements] products into DoD and civilian applications, ensuring downstream [heavy rare earth elements] industries have access to a reliable feedstock supplier.”

While the DOD deal does not mean MP Materials is abandoning its energy customers or focus, the company does appear to be to the new political environment. In its February earnings release, the company mentioned “automaker” or “automotive-grade magnets” four times; in its May earnings release, that fell to zero times.

Former Biden administration officials who worked on critical minerals and energy policy are still impressed.

The deal is “a big win for the U.S. rare earths supply chain and an extremely sophisticated public-private structure giving not just capital, but strategic certainty. All the right levers are here: equity, debt, price floor, and offtake. A full-stack solution to scale a startup facility against a monopoly,” Zumwalt-Forbes, the former Department of Energy official, wrote on LinkedIn.

While the U.S. has plentiful access to rare earths in the ground, Zumwalt-Forbes told me, it has “a very underdeveloped ability to take that concentrate away from mine sites and make useful materials out of them. What this deal does is it effectively bridges that gap.”

The issue with developing that “midstream” industry, Jacquez told me, is that China’s world-leading mining, processing, and refining capacity allows it to essentially crash the price of rare earths to see off foreign competitors and make future investment in non-Chinese mining or processing unprofitable. While rare earths are valuable strategically, China’s whip hand over the market makes them less financially valuable and deters investment.

“When they see a threat — and MP is a good example — they start ramping up production,” he said. Jacquez pointed to neodymium prices spiking in early 2022, right around when the Pentagon threw itself behind MP Materials’ processing efforts. At almost exactly the same time, several state-owned Chinese rare earth companies merged. Neodymium-praseodymium oxide prices fell throughout 2022 thanks to higher Chinese production quotas — and continued to fall for several years.

While the U.S. has plentiful access to rare earths in the ground, Zumwalt-Forbes told me, it has “a very underdeveloped ability to take that concentrate out away from mine sites and make useful materials out of them. What this deal does is it effectively bridges that gap.”

The combination of whipsawing prices and monopolistic Chinese capacity to process and refine rare earths makes the U.S.’s existing large rare earth reserves less commercially viable.

“In order to compete against that monopoly, the government needed to be fairly heavy handed in structuring a deal that would both get a magnet facility up and running and ensure that that magnet facility stays in operation and weathers the storm of Chinese price manipulation,” Zumwalt-Forbes said.

Beyond simply throwing money around, the federal government can also make long-term commitments that private companies and investors may not be willing or able to make.

“What this Department of Defense deal did is, yes, it provided much-needed cash. But it also gave them strategic certainty around getting that facility off the ground, which is almost more important,” Zumwalt-Forbes said.

“I think this won’t be the last creative critical mineral deal that we see coming out of the Department of Defense,” Zumwalt-Forbes added. They certainly are in pole position here, as opposed to the other agencies and prior administrations.”