You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

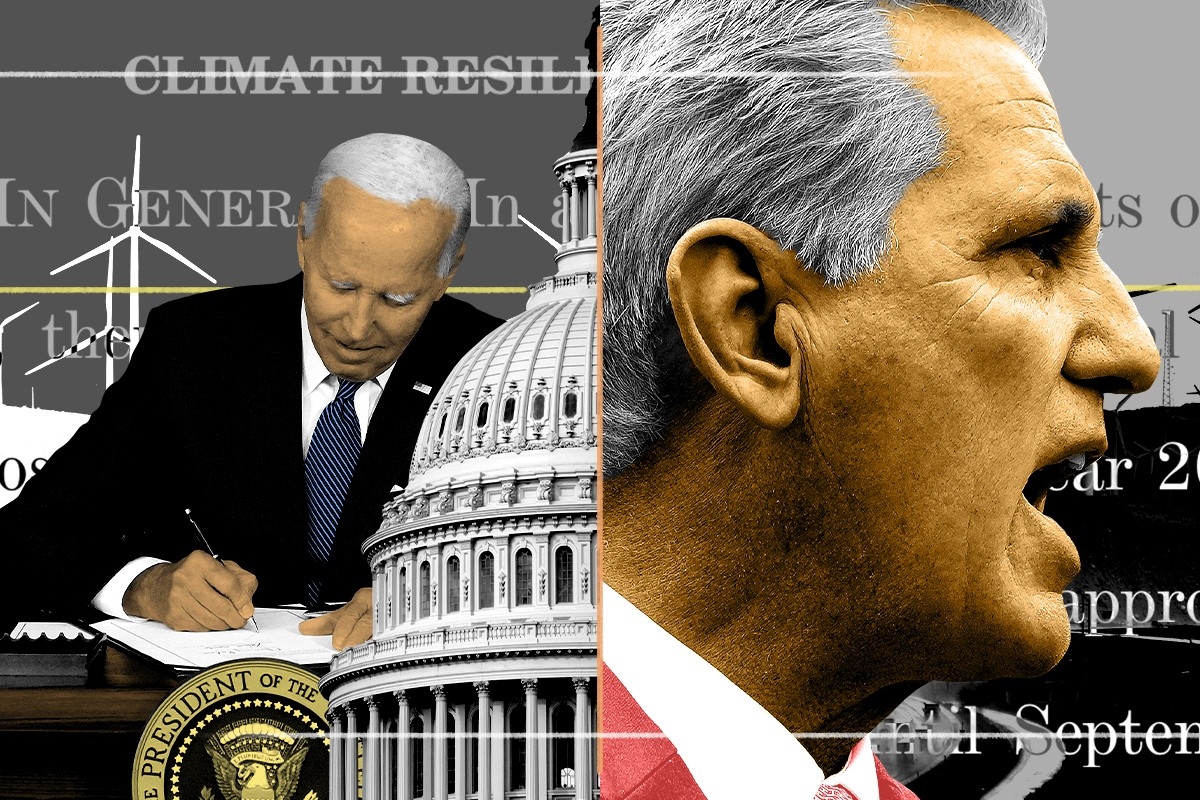

President Biden’s climate law gets a political stress test.

For the first time since it passed last summer, the Inflation Reduction Act — President Biden’s flagship climate law — is facing a threat of repeal.

The Republican majority in the House of Representatives has proposed essentially rolling back the law in their opening bid on negotiations with the White House to extend the government's borrowing limit and prevent a calamitous default. The GOP's proposal, called the Limit, Grow, and Save Act, would raise the debt ceiling for a year while slashing trillions in federal spending over the next decade.

While the Republican bill proposes deep cuts across the board, it takes a cleaver to Biden’s climate policy. Folding in the Lower Energy Costs Act, the first bill that the new GOP majority put on the floor, the act would repeal more than two dozen of the IRA’s clean-energy tax credits, including subsidies for renewables and electric vehicles. It would also defund programs meant to open new factories in the United States and gut climate-friendly programs popular with Republicans, such as generous subsidies for nuclear energy and hydrogen production.

Now, let’s get this out of the way: Neither the bill nor the negotiations around it are likely to repeal the IRA. Yet for the next few days or weeks, the IRA will likely appear to be in danger as nobody will quite say it’s safe out loud.

The Republican bill’s chief importance is as a piece of political posturing: Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy hopes to demonstrate that he has 218 votes to raise the debt ceiling and pass a budget, any budget, through his disorganized and dramatic caucus. Then he can open more serious negotiations with President Biden and Senate leaders about the debt ceiling and the year’s budget.

But to get there, he’ll have to keep the GOP’s right flank on his side first. McCarthy and House Republican leadership didn’t even want to include the IRA repeal in the Limit, Save, and Grow Act, but included it because the far-right House Freedom Caucus demanded it. That means House leadership must look completely serious about its intent to repeal.

At the same time, climate advocates must now mobilize around the IRA to demonstrate its importance to the public and prevent the Biden administration from sacrificing it in negotiations.

More broadly, though, this moment is a test for a few competing hypotheses about whether the IRA can survive — and about the future of climate policy in America.

To the set of political scientists, climate activists, and energy experts who championed the law, repealing the IRA would be so damaging to Republicans as to be unthinkable. That’s because Republicans’ constituents are, for now, reaping much of the IRA’s economic rewards. Up to two-thirds of green-energy investment nationwide is happening in GOP congressional districts, according to Politico. The all-important swing state of Georgia leads the country in clean-energy and electric-vehicle investments, forming the heartland of a new, vaguely banana-shaped “Battery Belt” that stretches across the largely Republican Southeast. Even beyond that region, Speaker McCarthy’s California district is one of the top two districts nationwide for utility-scale solar, wind, and battery plants.

This wasn’t an accident. The IRA is a product of the Democratic Party, so it was, yes, meant to do all those old-school Democrat things — encourage unionization, boost wages, and help revitalize the old industrial Midwest. But it was written by Democrats who see the party’s future in the Sunbelt suburbs and who prioritize decarbonization above other political goals. They knew — they couldn’t help but know — that much of the law’s investment would flow to the manufacturing centers of the American South and Southwest, where “Right to Work” laws restrict worker power and corporate-friendly policies reign.

On the other side, a set of critics allege that Republicans’ attack on the IRA doesn’t need to make political sense. Kate Aronoff, a New Republic staff writer who has been guardedly skeptical of the law, argued last week that House Republicans don’t care about the political fallout of killing the IRA because they’re protected from virtually any type of political fallout at all, thanks to gerrymandering, their deep-pocketed corporate donors, and a sharply conservative Supreme Court. In that view, the attempts to secure the IRA by appealing to Republicans’ constituents is futile: The party will simply do what it wants.

At stake here is a deep but important disagreement about the IRA. The flagship law aims to cleave fossil-fuel interests from the rest of the corporate bolus: to make it so attractive for banks, carmakers, electric utilities, steelmakers, manufacturers, and everyone else to decarbonize that they had no choice but to do so.Can that happen? Will that happen? This is the question on which the IRA’s advocates and its climate-friendly critics disagree. It is also is the question on which the fate of the IRA — and American climate policy — turns.

In her piece, Aronoff notes that fossil-fuel companies donated 13 times more to politicians in 2018 than renewable companies did. I found that to be oddly encouraging: If money alone is the issue, then the fossil-fuel industry’s alleged grip on the GOP could loosen over time. (The gap is already narrowing: Oil and gas-affiliated groups gave about six times more than renewables groups did in the most recent election cycle.)

The far more dangerous possibility for the IRA is that Republicans cannot be won over with money or argument. The party may just vibe with fossil fuels. Lawmakers and officials might feel an ideological affinity for oil and gas that goes deeper than those fuels’ economic or security benefits. During President Donald Trump’s term, he sometimes seemed to speak about fossil fuels not as a necessary evil, but as a positive good. This sometimes verged on trolling, but that was the point too: for Trump, at least, that it triggered liberals only underscored its correctitude. If that view were to break out into the party at large, it would spell an end to any kind of bipartisan shift on climate policy.

Which is all to say: Republicans probably won’t repeal the IRA this week.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Rob checks in with Near Horizon Group’s Peter Freed about the AI boom’s power needs.

Just a handful of tech companies plan to spend nearly $700 billion combined this year investing in artificial intelligence — and much of that money will go to data centers and the energy used to keep them on. How is this boom transforming the American energy system, and what does it mean for clean energy?

On this episode of Shift Key, Rob is joined by Peter Freed, a founding partner at the Near Horizon Group and the former director of energy strategy at Meta from 2014 to 2024. They discuss why data center developers opt for certain energy sources over others, why AI is driving an unprecedented off-grid natural gas boom, and why batteries now pair especially well with gas. Yikes!

This conversation was originally recorded for a webinar hosted by Heatmap Pro. Shift Key is hosted by Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Here is an excerpt from their conversation:

Robinson Meyer: We know there’s this giant capex surge coming from the hyperscalers. I mean, it’s reached the point now where tech companies’ stocks suffer when they announce investment because they seem to be in an arms race of spending on data centers. We were just talking about the behind the meter gas boom. There’s a lot of renewable energy developers in this audience, or battery developers. How should they be thinking about this moment and what do they need to be doing to make their projects or to work with data center developers in the most attractive way?

Peter Freed: I’ll bring us back a couple of minutes to when I said, look, if you’re a data center developer and you’re building gas plus storage and you’re thinking of that as a pretty complicated thing, someone is really going to have to work out on explaining why the introduction of a variable renewable resource into that configuration is worthwhile.

And obviously there are people that believe that that’s true. Intersect believed that that was true and it worked out really, really well for them. There are ways to tell that story. And I think that the renewable energy development community probably still has some work to do to help explain that. So that’s sort of thing number one — like, the closer you get to the operations of the data center facility, the more work you’re going to have to do to explain why you believe that the integration of renewables into that makes sense.

Now, you can remove yourself somewhat from the actual operations of the facility. And this is where we get into bring your own capacity conversations. And you know, there’s been some really interesting stuff sort of talking about, okay, maybe there is a utility which has sufficient wires capacity as — and like, there’s enough room on the transmission lines to plug a data center in and turn the lights on, but they don’t have enough market capacity. Like, they don’t have enough of the financial products required by the RTO that they operate in to serve that facility. And so that can become an interesting opportunity for renewables in particular, storage in particular, trying to figure out how to put together these bring your own capacity products to serve data centers.

And I’ll say, you know, when I first heard about these bring your own capacity opportunities, I thought that they were pretty niche. I was like, okay, well, you know, a utility has sufficient wires capacity to serve a giant data center, but they don’t have capacity in the market. Like, that feels like something that’s not going to happen that often. But apparently, I mean, I was incorrect.

You can find a full transcript of the episode here.

Mentioned:

Breaking Down the Doomsday AI Memo That Spooked Markets

Inside Form Energy’s Big Google Data Center Deal

The New York Times on AI’s polling problems

Previously on Shift Key: What’s Really Holding Back New Data Centers

This episode of Shift Key is sponsored by …

Heatmap Pro brings all of our research, reporting, and insights down to the local level. The software platform tracks all local opposition to clean energy and data centers, forecasts community sentiment, and guides data-driven engagement campaigns. today to see the premier intelligence platform for project permitting and community engagement. Book a demo today to see the premier intelligence platform for project permitting and community engagement.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.

This transcript has been automatically generated.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Robinson Meyer:

[0:08] Hi, I’m Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News. It is Wednesday, February 25th. I don’t know if you were paying attention, but on Monday, the S&P 500 dropped over 1%, as did the Nasdaq, because of a memo from an investment research firm that was basically a science fiction short story. We’ll put it in the show notes, but it argued that AI is going to work, is going to be so successful that it will in fact cause mass unemployment and trigger a recession. Now, it wasn’t the first memo or argument that there might be bad effects for the economy if huge amounts of white collar workers are put out of work.

Robinson Meyer:

[0:46] But it was the first that argued it may be in a persuasive way, in a mechanical way. And for whatever reason, it caused absolute carnage in the stock market. And I think it showed not only that artificial intelligence is the biggest story in the American economy right now, something we already knew, but that nobody knows what’s going on with it. And that holds true for data centers, which are the biggest topic in energy and climate and electricity, but that are changing in a way that is very hard to track. And so on this episode of Shift Key, we’re going to talk to someone who is tracking the way that data centers are changing. A year ago, Jesse and I spoke with Peter Freed about exactly what the data center buildout was doing for electricity and renewables. Peter is great. He’s a founding partner at the Near Horizon Group. He has over 20 years working at the nexus of clean energy, climate, and computing.

Robinson Meyer:

[1:31] And I think most saliently for 10 years from 2014 to 2024, he was director of energy strategy at Meta. He was right up against the coalface of energy procurement for data centers. A year ago, we talked to him. We learned a lot about what data centers meant for electricity and renewables at that moment. But a lot has changed since then. And so on Monday, the same day the stock market was down 1%, I talked to Peter Freed for a Heatmap Pro webinar about how data centers have changed over the past year and what he thinks they’ll mean for electricity and renewables and energy and emissions going forward into 2026. It was a really educational if disconcerting conversation. We talked about the enormous surge, the $600 billion to $700 billion of investment in data centers that are going to happen this year, why data centers are driving a huge off-grid natural gas build out now, and why data centers are also splitting the battery industry from the renewable industry. It was really, really interesting. I learned a lot, and we liked our conversation

Robinson Meyer:

[2:30] so much that we’re releasing it now as a special Shift Key episode. Thanks as always for listening, and let’s go to that conversation now.

Robinson Meyer:

[2:41] Hello, everyone. I am Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News, and you are watching Heatmap Pro’s special live webinar presentation of Shift Key. It is Monday, February 23rd, and I’m going to welcome our guest in for a moment. You can already see he’s joined us here in the virtual recording studio. But before we get started, I just want to put a word in for our sponsor today, keeping it all in the family. Our sponsor today is none other than our very own Heatmap Pro. If you want to keep following how data centers are reshaping the energy transition in practice, that is the work we do every day at Heatmap. Our pro team tracks where energy and data centers projects move forward, where they get delayed or canceled, and how community response shapes outcomes. We have data nobody else has on renewable energy projects as well as data center projects and the political risk that they’re facing. If you’re interested in learning more about the software, visit heatmap.news/pro. That’s heatmap.news/pro. Okay, let’s get started. Peter Freed is our guest today. He’s a founding partner at the Near Horizon Group. He was director of energy strategy at Meta from 2014 to 2024. And he brings to this conversation over 20 years of working at the nexus of

Robinson Meyer:

[3:51] clean energy, climate, and recently data centers. It’s always great to talk to him. Peter, welcome to the Heatmap Pro live Shift Key.

Peter Freed:

[4:00] I’m so excited to be here. It’s been like a year since we did one of these. So there’s a lot to talk about.

Robinson Meyer:

[4:07] There’s so much to talk about. Okay. So I want to actually start exactly there. So the last time we talked, it was February 2025. It’s been exactly a year. Let me start by asking, are you busier now than you were a year ago?

Peter Freed:

[4:21] That’s a great question. So, you know, I have built my current professional life on trying not to be too busy. So I’m doing okay at that. I could certainly be unlimitedly busy right now. There is a lot going on. The market has certainly not settled down. In fact, if anything, it’s gotten crazier. So yeah, it’s pretty nuts right now.

Robinson Meyer:

[4:41] So a year ago when we spoke, one of the key themes is the amount of speculative froth in the market that I think your term was, you know, two guys in a pickup truck announced they would be data center developers, and then they were treated as data center developers, and that was entering the math. Has any of that froth started to fall out? Or is it more intense now than it was a year ago?

Peter Freed:

[5:04] So the answer is yes and no. I think a couple of different things are happening. And I always find myself when I’m talking to you, Rob, referring to your own reporting, but I’m actually going to start there. Rob does not pay me to do this. I just really like the work that Heatmap does. So I think like a lot of the speculative activity that began in 2024, like that we were talking about a year ago in early 2025.

Peter Freed:

[5:26] Especially from inexperienced developers, well, we are now starting to see some of those projects kind of falling out and maybe the less polite way to say it would be falling apart. Like, you know, these are very complicated projects. They are getting bogged down in permitting processes. They’re getting bogged down in community opposition and all of this other stuff. And so I think that, you know, Heatmap Pro had done some really interesting reporting around the number of projects that had failed in 2025 and that that was growing. And I’d provided some comments on that then. But I think that’s what we’re starting to see, right? Like, I am someone who believes that maybe 10% of the projects that have been proposed around the country will actually end up being fully built out data center campuses. And part of what falling apart means or falling out of that process means is just that like projects will be canceled in various ways. Commercially, you won’t really see that. Maybe in the regulatory process or utility interconnection proceeding, the timelines will be so long that someone will fail to do it. The most public stuff, of course, is what we’re seeing around community opposition and these, you know, town hall meetings where dozens of people will show up and be protesting a facility for whatever reason. And then I think ultimately the financing, you know, people have to figure out how to secure the money to build these projects.

Peter Freed:

[6:41] And as it turns out, it’s a lot of money. And while there is capital available, like figuring out how to put those pieces together has been challenging. So I think that’s the yes stuff has fallen apart side.

Peter Freed:

[6:52] On the other side, there is still a ton of activity going on, people bringing new things to the market. And, you know, I can’t tell you how many like

Peter Freed:

[7:02] calls I get where someone’s like, hey, I’ve got a refrigerated warehouse that has electrical capacity. Can I turn that into a data center? So that sort of stuff is still happening. And I think maybe the difference is people have realized a little bit more that if you have a refrigerated warehouse that you want to turn into a data center, that maybe you shouldn’t do that yourself. And so I think what I’m seeing a little bit more of is partnership between the more established and experienced data center developers with people that bring other pieces of the puzzle to the table. And so there’s still a lot going on, but I do think that maybe the level of complete ridiculousness where it’s just very random people trying to do very random things, like maybe that’s coming down a little bit.

Robinson Meyer:

[7:47] We’re going to talk about every facet of this question, but what is the biggest bottleneck right now for projects?

Peter Freed:

[7:54] So I bet if you asked five people in the industry that question, you get five different answers. I have always said, and I think I said this to you the last time we talked, that I am very confident in the ability of the power sector, not necessarily the utility sector, but the ability of the power sector to meet the needs of the AI demand signal. And I do think that that is continuing to be the case. Last time we spoke, you all had done some really good reporting around the constraints on gas turbine supply chains. And those supply chains were indeed constrained. They’re still relatively constrained. But what we’re seeing is people are building data centers with a whole bunch of different thermal generation technologies, very small reciprocating engines, simple cycles, aeroderivatives, like all of the different flavors of put gas into it, power comes out. And so I think, you know, we’re definitely seeing that sort of thing happening more and more. And so, you know, the power sector is figuring out how to do this. So there are still plenty of people that say, oh, the power sector is the big bottleneck. I’ve never really thought that the power sector would be the key bottleneck. It might just look different than we thought it was going to look.

Peter Freed:

[9:04] I am hearing on the ground that now this is something that I’ve been wondering about slash worried about for a long time. Construction labor is becoming very constrained in many markets, in particular skilled trades. So skilled electricians have been a group of workers that have always been challenging to get enough of a data center construction. And now we’re ballooning the industry. So skilled electricians are an issue. Long lead equipment has and will continue to be an issue. So this is not necessarily the generators themselves, but on the electrical side, we’re talking circuit breakers, we’re talking transformers, and, you know, people are ramping up production capability, people are trying, you know, there’s a couple of startups that are doing like new cool power electronics for that kind of stuff. So that’ll need to catch up. But, you know, these are sort of the ups and downs. Is it power? Is it labor? Is it long lead equipment? Is it chips? Is it, you know, you get all of those answers even today.

Robinson Meyer:

[9:59] I feel like a year ago, there was this idea that only renewables had speed to power. And then really, X.ai and Elon Musk demonstrated that you could still get gas turbines if you didn’t care about the pollution that you pumped into an urban neighborhood or any of the other externalities. Do renewables still have an edge when powering data centers? Or has X.ai and this idea that there’s all sorts of gas available to you if you care far less about the externalities or are willing to pay to not care about

Robinson Meyer:

[10:30] them. Has that kind of changed the game?

Peter Freed:

[10:32] I think that there are certainly companies which still care about the clean aspect and the hyperscalers themselves. So really, we’re talking, you know, Meta, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon who have public clean energy commitments.

Peter Freed:

[10:46] You know, you look at a company like Google, which I think very philosophically has been chasing this for a long time. We’ve seen them do all sorts of interesting things. They appear to still be quite interested in using renewables as part of the actual power solution for the data center. So they recently acquired Intersect Power. That is a company which was formed around the idea that you could do these campuses that included solar and storage and some gas. But like mostly it was a clean orientation on that. Google has also announced a CCS project. So that’s sort of one bookend. The other bookend, hopefully, is that people continue with their existing renewable energy commitments, which just say like, all right, however much power we’re going to use, we’re going to make sure that a similar quantity of power is deployed onto the system. And so, you know, that that is still happening. The whole like speed to power equals the fastest way to get data centers on and that we’re going to do renewables as part of that. I’m not seeing a huge amount of that happening right now. Now, you know, Cloverleaf Infrastructure is another fantastic company that has done some really, really creative things working with utilities to put portfolios together that are largely clean portfolios and bring data center capacity on. But the other thing that I’ve been saying to people for a while now is like, if you figure out how to do ...

Peter Freed:

[12:09] Very rapid deployments with gas. And that in and of itself is actually extremely complicated. Like the engineering required to get all of the power quality and reliability characteristics that you would get from a grid interconnection from a standalone power plant. You’re going to do that with gas turbines and storage in most cases. Adding the additional layer of renewables to that is mostly seen as a complicating factor right now. So, you know, there’s a bit of interest, but it’s not universal interest.

Robinson Meyer:

[12:39] But you’re also describing, I think, a pairing that might be normal for data center developers to think about, but a pairing that I think in climate world, we don’t think about that much, which is gas plus batteries. Oh, yeah. Which we normally talk about solar plus batteries as being what, you know, the kind of classic pairing, but gas plus batteries is developers value it because it basically adds reliability onto their gas.

Peter Freed:

[13:01] That’s right. So, So, you know, data center reliability, the industry parlance is like nines of reliability, right? So that means like 99.999, five nines, 99.99. And so if you want reliability that is nines coming after your 99% uptime, you typically do have to add some battery storage. And data centers, by the way, I always used to say like data centers are the biggest battery storage installations on the grid and have been basically forever because they have uninterrupted power supplies inside of the facility. So these are batteries that are inside of the data centers. They usually have a minute and a half to five minutes of backup capacity. And this is for little blips in power quality or, you know, something happens. We’re talking about utility scale batteries, multi-hour batteries now, where people are adding that to the design of the facility in order to get you

Peter Freed:

[13:56] those higher reliability numbers. And some people are requiring that, some people aren’t, and it’s driven as much by cost as anything else.

Robinson Meyer:

[14:04] Are most of the batteries like lithium-ion, standard, multi-hour ... You know, battery installations, or are we seeing these more exotic or kind of frontier batteries with like multi-day storage coming online at projects?

Peter Freed:

[14:16] Yeah. I mean, so right now it’s off the shelf lithium ion, either two- or four-hour, and there’s a lot you can do with that. There’s a much more interesting conversation, which I think we will have at some point in the next hour, 45 remaining minutes around like what you might do with those longer duration batteries. You know the simple fact is there just aren’t enough of those yet to sort of see more deployments like you know i was chatting with some of the folks at form not so long ago i was like oh my god like such a great technology like how do we get a 100X your current supply chain onto the market because think what we get you know and it it just takes time it.

Robinson Meyer:

[14:56] Takes time yeah yeah before we move on from kind of where we’ve been where we’re going last year when we talked it was right after DeepSeek. And actually, there’s been reporting today that DeepSeek is about to come out with its next model. The last time this happened, it was shocking to people because the DeepSeek model seemed to use so much less electricity than any of the current American frontier models. And there was this discussion of Jevons Paradox, which to vastly simplify, is the idea that as something gets cheaper and less energy intensive,

Robinson Meyer:

[15:28] we tend to use more of it rather than less. We tend to enjoy those energy savings by using more of the thing rather than, you know, decreasing our overall energy usage. So a year after DeepSeek with another model on the horizon, has the idea that AI is going to be subject to Jevons Paradox borne out, or has all the use been at these frontier models?

Peter Freed:

[15:52] I am so glad that you asked this question, because actually, like, Jevons was getting so much discussion through sort of the back half of 2024 and into 2025. And then I feel like people have sort of stopped talking about it. I remember, actually, when we talked about it on the last shift, because Jesse did such a nice job of explaining it very professorially. And I was like, oh, that’s that’s why you’re a professor. And I’m not. But yeah, people get it at this point. And the short answer is, yes, Jevons is holding. It’s happening. I think if you look at the efficiency gains that are coming in, facility design to some extent, but mostly algorithmic design and chip design. I don’t remember what the stats are, but if you talk to someone from Nvidia about the efficiency of their chips, it’s remarkable how much efficiency they have brought into the design of those chips. That’s true across the board on all of these new custom silicon and all of these other things. And by the way, AI demand continues to surge through the roof. So, you know, Jevons is something which has applied through history since it was identified pretty selectively. Like it definitely doesn’t apply to everything, but by all accounts, it applies to this. I’m not an economist, but, you know, we are seeing efficiency gains in all of the places that people thought we would see efficiency gains and AI consumption only continues to climb. And in fact, if anything, we’re seeing an acceleration of the climb.

Robinson Meyer:

[17:12] Back two years ago, when we really started talking about the data center story, the idea was, well, we don’t know whether these power, this huge amount of load growth is going to show up or not on the data center side, because at the same time we were beginning to talk about massive load growth, Nvidia was also announcing, you know, its new chip, which uses 99% less electricity or 90% less electricity. And it’s now been several years since then. Those chips are deploying. I mean, they were frontier chips, so they’re still very expensive and supply constrained. But it’s not like the load growth story has gone away, even as those chips has diffused.

Robinson Meyer:

[17:48] What is the biggest trend you’re seeing right now that you feel like nobody else or or the market or the rest of the industry hasn’t caught up to yet? And if you want to affirm another trend on the way here and say, ah, people know about this trend, but it’s actually a big deal. You should do that, too. But like, what’s the trend nobody’s talking about yet?

Peter Freed:

[18:06] Yeah, I mean, OK, so I think we’ve already been talking about this a little bit, but but going back to 2025 to now, so call it the last year, I do think gas is like the idea that we’re going to see behind the meter gas of one sort or another that has arrived. So, you know, it was probably I feel for companies that were really chasing that hard in early 2024 because deals weren’t getting done. But now there are a lot of deals that are either done and not talked about yet or in the works right now. So we are seeing a ton of behind the meter gas. All of these are almost all of them are what we would call bridge to grid. So it’s you know, you’re you’re building a gas fired power plant with the notion that at some point you get connected to the power grid. So I think that’s the trend that that has certainly been affirmed. It just took a little bit longer than I think people thought.

Peter Freed:

[18:55] The one maybe that that I think is being talked about in a way that I think

Peter Freed:

[19:00] of it somewhat differently is flexibility. And, you know, there was all of this conversation around like flexibility is going to be the key to all of these different things. And, you know, a bunch of different companies were pursuing it. Google has demonstrated repeatedly that technologically it’s possible to work with the compute loads inside of a data center. And basically you modulate compute as a means of adjusting power consumption. So we know that technologically it’s feasible. We also haven’t seen outside of Google a lot of companies successfully doing that at scale. There’s a bunch of startups that are sort of chasing different flavors of it. I think what we are also finding is that you can achieve, back to the battery conversation, you can achieve a lot of that flexibility synthetically with batteries.

Peter Freed:

[19:49] And where I feel like we are right now, and we can and should talk more about this, is that all of the pieces are on the table. All the puzzle pieces are out on the table now. We don’t need new puzzle pieces, but we do need people to sort of put those puzzle pieces together in a repeatable and scalable way that we haven’t seen yet. And that means, you know, basically.

Peter Freed:

[20:11] Technology solutions, potentially, you know, touching the operations of the data center, although ideally not, at least in my view, like if you’re going to work on one of these, make it look the same as it always looked at the data center operator and you just sort of handle it. Then you need a software solution that finds the actual configuration and makes that work. And there’s some startups that are chasing that. And ultimately you need the utility or the grid operator to sit in the middle of all of that and say, yes, maybe I couldn’t find this myself, but I concur with what you are saying. And therefore I am validating the underlying value proposition to the data center operator or owner that’s going to have to pay for that in order to unlock new capacity. So I think we’re getting closer to the cusp and I’m hoping that 2026 is the year where we see more of that. So we’ll see.

Robinson Meyer:

[21:00] I want to go back to something you said at the very beginning of that answer. That was all so useful. And we’re going to touch on so many parts of that, but I want to go back to something you said at the very beginning, which was that this is that behind the meter gas has showed up, that new data center projects are building large scale gas installations as they wait for a hookup to the grid. We’ve been observing this and covering this at Heatmap, but to describe it as an industry-wide trend does seem like a huge deal because we’ve talked about data centers for the past two years as an electricity story. And when we look at the electricity statistics, what we see is 90 percent, 95 percent of new capacity coming online is renewables. And there’s a reason why renewables would like perform especially well in capacity statistics rather than kind of power statistics. But. This huge amount of capacity coming onto the grid nationally according to eia is renewables but it sounds like kind of what you’re saying is that data centers are now a gas demand story and are hooking deep into the gas system and we should expect to see that demand showing up in the gas system even before we see it in the power system and so the fact that there’s all these data centers using electricity we might not see their electricity demand in grid statistics that’s

Peter Freed:

[22:18] Right because if you’re about if you’re a fully private behind the meter gas project you’re not reporting no one’s reporting that to anybody now you know, Maybe on the gas demand side, yes, although many of these projects are basically being built on top of the big gas plays, right? You know, that’s why we’re seeing so much of this in West Texas and some of this stuff in Ohio. And so where that would show up in reported statistics and when is a big question. One could imagine a universe in which, you know, you’ve built this behind the meter gas-fired solution and your grid interconnection is going to take five years or seven years.

Peter Freed:

[22:59] Maybe at the end of that time when that plugs into the system, then it shows up somewhere. But there’s actually a bunch of really interesting questions about what happens to those gas-generating assets when the grid connection comes along, right? So, you know, there’s like the VoltaGrid model, which is a company that X.ai has worked with. They’ve got a pretty long track record where a lot of times they literally take the generators, they put them on the back of a truck and they take them on to the next project. And so, you know, some of these projects that people are doing with relatively small, like reciprocating engines, which don’t have the world’s greatest heat rates and they’re not that efficient. Maybe they’ll go on to the next project. In other cases, maybe those generators become the backup generation solution to the grid connection and suddenly go from being a prime power source, so running almost all of the time, to running 20 or 30 hours a year when you’re testing, you know, just for testing. And then the middle ground, I think we’ll see some of this too, is those resources become grid resources. So either they’re being dispatched economically as a grid resource, or it goes into sort of the planning paradigm of the local utility. And the costs have already been borne by the data center customer. And so maybe that works from kind of an affordability perspective or otherwise. And I think we’re at the earliest stages of thinking about that. And maybe just because I like to throw out.

Peter Freed:

[24:23] Ideas for people. Like one of the things that I’ve been wondering about having now seen so much of this happening is, could we be a little bit more thoughtful or strategic about how we’re doing this? I’ll put a little shout out into the utility practice at McKinsey. I really like that team. I find them very thoughtful. And so we’ve just been starting to like virtual whiteboard. Like if you wanted to bring an overall grid orientation to like all of these random behind the meter data centers, which mostly just work in where is there land with gas available? That’s sort of the driving factor, right? I need a big piece of land that has gas availability. Could we be more strategic about that from eventually all of this gets hooked into the grid seven years from now, whatever it is like, is there a way to add like one little thumb on the scale of strategy and planning that says I would optimize this location versus that location or I would do it this way versus that way? And it’s really early days, but that’s one of the things that I’ve been sort of pondering a bunch lately is like, is there a better way to do this that feels more strategically oriented than just like finding the biggest piece of land you can with gas available?

Robinson Meyer:

[25:30] Well, it sounds like what you’re also talking about is the massive gas buildout happening totally outside the reach of any utility IRP, totally outside of any utility planning process, massive gas electricity capacity buildout that right now we don’t see on the grid, but at some point in the future could surge online as this bottleneck works its way through. There’s a great question in the chat that I want to ask, which is what percentage

Robinson Meyer:

[25:53] of data centers total expected demand is the bridge being built for? So if it’s a 100-megawatt project, I mean, are developers building 100 megawatts on site of gas and then waiting for 100-megawatt interconnect? Or is it like they build 50 megawatts and then they wait for the rest, the next 50 to show up?

Peter Freed:

[26:12] You know, I can’t speak for every project, but within the projects that I am familiar with, it’s 100% of the projected project load. You know, these projects ramp through time, right? It’s not like if you want a one gigawatt data center, you don’t just turn on a 1-gigawatt data center. In fact, a gigawatt data center could take years to ramp up, not just because of construction time, but because you have to put the computers in, you have to turn them on, you have to make sure they all work together. The old industry rule of thumb used to be 50 megawatts every 90 days or so at a given site. Now it’s accelerated some, but it’s not like you’re just turning on 100 megawatts every couple of weeks, you know, like it takes time. So anyway, what I would say is at least the projects that I’m familiar with, people are... Not deploying as much gas as they possibly can. And then when the grid connection shows up, you get into that conversation that we were just having, what do you do with those generators? Or depending on the size of the site, in some cases, they think of them as additive. So if you’re going to do 500 megawatts of behind the meter generation, and you’ve got a 500-megawatt grid connection, in some jurisdictions, you might say, well, that’s 1,000 megawatts of capacity, You’re actually probably more likely you’re going to work with the utility and it’s 750, right? The grid connection will take more and suddenly now the utility has a peaking asset sitting there that helps them manage it.

Peter Freed:

[27:38] Whereas in Texas, interestingly, which is the hottest, you know, this is where a great significant percentage of all of this is happening. With SB6, you can’t, that’s the Senate Bill 6 that, you know, was related to data centers coming online and how you’re going to think about that from the perspective of the grid. And basically, you can’t get a new grid connection without somewhere adding new generation associated with it. And so interestingly, like, there are some proposals and projects that I’ve seen or heard people talking about, where actually the idea is that you build a bridge project to a large scale gas fire generator and still get a grid connection. And that large scale gas fire generator, usually a combined cycle unit, is helping accelerate the interconnection timeline to the grid, because basically what you’re saying to the grid operator is like, I’ve got enough generating capacity sitting here that I can cover this entire load if I need to, but it would still be more efficient. For everybody to have this thing connected. And, you know, so one of the questions that’s really interesting is, do those folks get interconnected to the grid faster because there’s some big resource sitting there? And I think probably the answer is going to be yes.

Robinson Meyer:

[28:52] We know there’s this giant capex surge coming from the hyperscalers. I mean, it’s reached the point now where tech companies’ stocks suffer when they announce investment because they seem to be in an arms race of spending on data centers. We were just talking about the behind the meter gas boom. There’s a lot of renewable energy developers in this audience or battery developers. How should they be thinking about this moment and what do they need to be doing to make their projects or to work with data center developers in the most attractive way?

Peter Freed:

[29:22] I’ll bring us back a couple of minutes to when I said, look, if you’re a data center developer and you’re building gas plus storage and you’re thinking of that as a pretty complicated thing, someone is really going to have to work out on explaining why the introduction of a variable renewable resource into that configuration is worthwhile.

Peter Freed:

[29:45] And obviously there are people that believe that that’s true. Intersect believed that that was true and it worked out really, really well for them. There are ways to tell that story. And I think that the renewable energy development community probably still has some work to do to help explain that. So that’s sort of thing number one, like the closer you get to the operations of the.

Peter Freed:

[30:08] the data center facility, the more work you’re going to have to do to explain why you believe that the integration of renewables into that makes sense. Now, you can remove yourself somewhat from the actual operations of the facility. And this is where we get into that, what, bring your own capacity conversations. And, you know, there’s been some really interesting stuff sort of talking about, okay, maybe there is a utility which has sufficient wires capacity as — and like, there’s enough room on the transmission lines to plug a data center in and turn the lights on, but they don’t have enough market capacity. Like, they don’t have enough of the financial products required by the RTO that they operate in to serve that facility. And so that can become an interesting opportunity for renewables in particular, storage in particular, trying to figure out how to put together these bring your own capacity products to serve data centers. And I’ll say, you know, when I first heard about these bring your own capacity opportunities, I thought that they were pretty niche. I was like, okay, well, you know, a utility has sufficient wires capacity to serve a giant data center, but they don’t have capacity in the market. Like that, that feels like something that’s not going to happen that often, but apparently I mean, I was incorrect.

Robinson Meyer:

[31:30] How would this happen?

Peter Freed:

[31:31] Yeah. I mean, basically like the generation that they’ve built or contracted with is, is sufficient to serve the needs of their existing customer base. And also there is room on the physical infrastructure that underpins that for growth. You know, a lot of, you know, utilities are rarely building exactly to what they need in that moment, right? There’s always some anticipation of growth. And so, you know, particularly with a utility which maybe doesn’t have a huge generation fleet, which is procuring capacity from the market, you could find yourself in a situation where their physical infrastructure could accommodate new load, but they don’t actually have the market product to serve it. And so, you know, either the answer to that is the utility itself goes out and builds a whole bunch of new, probably gas-fired generation to get sufficient capacity to serve, or the customer can bring its own capacity. And if you look at, for example, like some of the nuclear deals that have happened with existing plants or with upgrades or some of those things, like assuredly, the capacity elements of nuclear service are useful in putting together a solution to serve new data center loads across those markets.

Robinson Meyer:

[32:44] If we’re talking about data centers now being major gas fire generator, you know, if you’re talking about putting 500 megawatts or gigawatt of gas generation on a data center site, then suddenly these things shift from having the footprint of a classic cloud data center or even an Amazon warehouse to being a major, I mean, having literally a gigawatt scale power plant in your backyard. So we don’t have these polling results out yet, but at Heatmap Pro, we do periodic polling on the community support for data centers. And we ask questions like, would you welcome a data center in your community? The most recent poll, which is not out yet, we’re going to publish it later this week, is net 24, is negative 24. And more than half of respondents would oppose a data center in their community. It’s a huge decrease in our data set. But do you see backlash to the pollution aspect of data centers or is it to the whole package?

Peter Freed:

[33:43] I think it’s the whole package. And my guess would be that the pollution element makes it worse. So, you know, public sentiment polling for AI as a technology category is extremely poor. Like, I think there was a really interesting article in The New York Times this weekend about how, like, of all of the technology booms where there’s polling data, this one is by far the worst. Like people historically have gotten very enthusiastic about this kind of stuff. And like the public is just very skeptical about the benefit.

Robinson Meyer:

[34:11] In part because the CEOs of the companies tell us it’s going to be bad. Mark Zuckerberg told us that he was going to connect the world, you know, 20 years ago. People had concerns, but it seemed like people were. I mean, they turned out, of course, that technology had massive downsides. But it seems like everyone was pretty jazzed about it. But now even the CEOs are like, this is a major problem. We aren’t able to stop it. And that’s why we’ve adopted these arcane corporate structures in order to contain the technology that we are. Right.

Peter Freed:

[34:40] So with that said, you know, I think. A data center is the closest physical manifestation of AI that a person can encounter right now outside of like robots in your house. And so I think I think in general, public opposition to data centers tends to reflect that public sentiment. And on top of that, pollution elements. Yeah, I don’t think that that that is going to be particularly helpful from a public sentiment standpoint. Now, the question is, does the introduction of renewables to that power solution really obviate any of the concern? And my guess is that the answer is no, because, you know, if it’s a gigawatt data center with a gigawatt of gas-fired power generation or 500 megawatts because there’s a big solar and storage, you know, I don’t think the public generally cares. And so, you know, what I expect that we will be seeing is more and more of these gas-fired projects being in places with favorable permitting regulations. So, you know, think...

Robinson Meyer:

[35:43] Unincorporated county land in this which yes

Peter Freed:

[35:46] We’re already seeing a lot of that places where there’s already industrial zoning and like people you know places and communities that are used to this kind of stuff i think that’s much more likely.

Robinson Meyer:

[35:55] I was going to ask if we’re seeing new hot spots because the hot spot previously was the mid-atlantic you know georgia northern virginia and texas and you already mentioned texas but are there different hot spots emerging slash is construction of PJM, the Mid-Atlantic and the Upper Midwest fading?

Peter Freed:

[36:13] No, nothing is fading. I think West Texas is really like the main story. You know, Meta announced a data center in El Paso and, you know, people were sort of like, oh, El Paso, so interesting. But now the whole Abilene, Midland, Waco, like I would not be at all surprised if within a year or two, if not a true availability zone for the cloud, But that will become a new major computing region. Like enough activity is happening there that we’re just going to see that spring up. You know, I’m hearing a lot of rumblings around Wyoming. Again, not the world’s most populous state. A lot of gas infrastructure runs through it. There have been, you know, Microsoft has got a project there. Meta’s got a project there. I think OpenAI has been rumored to have a project there. So, or Crusoe, you know, maybe with OpenAI attached. Anyway, so, you know, there’s I think Wyoming is going to be a place and then, you know, really anywhere else where you have less dense population zones and the availability of gas may eventually become something.

Robinson Meyer:

[37:15] When we talk about these hyperscalers, so we’re talking about oh, Meta has a project there, Oracle has a project there, OpenAI has a project there. Is that because it’s the hyperscalers that are still driving most of the demand? Or do they act as water buffalo? And then, you know, the flock of independent data center developers kind of follow them because they’re assumed to have detected some price signal. And so you get these big projects that are like the big Meta gigawatt-scale project. And then you get all these little AI data centers around it, which are like independent developers hopping on to what they think might be good price action or something.

Peter Freed:

[37:53] So it’s somewhere in the middle. So all of the major hyperscalers are still self-performing. So they’re building their own data centers. And then there are large developers who are building data centers to also serve those companies. So basically the demand signal for large-scale compute is the four hyperscalers that we’ve already talked about, plus OpenAI and Anthropic, basically. Like that’s pretty much it. Oracle, to the extent that they’re a player here, is largely just a sleeve for OpenAI demand. You know, some exceptions, like they have their own businesses, but a lot of what they’re doing is that. And so almost everything we’re seeing is just consolidating around six companies, which is a very weird market when you think about it.

Robinson Meyer:

[38:41] Is there is someone who’s doing Anthropic’s?

Peter Freed:

[38:44] Actually, the information just had some really interesting reporting on this over the weekend. So right now, like the expectation has been that Anthropic is doing leasing. Either they’re doing direct leasing. So, you know, where they would have more control over how a data center was constructed and built, or they’re buying cloud capacity from the likes of Google Cloud or Amazon Web Services or what have you. So they are not building any of their own data centers, at least nothing that’s been publicly reported. And actually, interestingly, that article that I mentioned that came out over the weekend identified that OpenAI had had these ambitions to build their own data centers and has largely shelved those because for a variety of reasons, including securing financing, they’re mostly also going this leasing route, at least right now.

Robinson Meyer:

[39:28] Well, that bleeds me. So how are hyperscalers navigating, you know, a number of hyperscalers or a number of these big AI companies, notably OpenAI and Anthropic, are at least reportedly trying to IPO this year? That means they need a lot of money. They’re also facing ballooning computing needs. How is that affecting the real world of data center development?

Peter Freed:

[39:50] So we’ve just talked about, in a sense, how the demand signal, I wouldn’t even say consolidated. It was never like, if anything, it’s grown a little bit because now you have two frontier labs along with the four hyperscalers. But you’ve got a very small pool of very large demand. And also what’s happening is I think we are starting to see some consolidation on the capital availability side because the numbers are so large. right? You know, we’re talking hundreds of billions to a trillion plus dollars in the next handful of years. There are very few capital providers that have that kind of money. So the hyperscalers have been using their own balance sheets. They’re flush. But even that is not enough. They’re starting to go out and look for creative sources of financing. There’s large private equity funds that have been playing in this space for a long time. They continue to play. And then ultimately, and we’re seeing this, right, like sovereign wealth funds, that’s kind of the type of money that we’re talking about. And a lot of Middle Eastern money has been getting involved here, other sovereign wealth from around the world, Southeast Asia, etc. So in my view, we are actually seeing both a consolidation of capital supply and demand on the other side and the credit that goes along with that. And so it’s going to be really, really interesting to sort of see how this all shakes out, in part because...

Peter Freed:

[41:16] A lot of the capital providers are relatively risk averse. Like, you know, last year there was a bit of a fear of missing out flavor. And so we saw people at least making big announcements about money that they were going to earmark for stuff. I would say this year, it seems to me that people are really asking real questions around risk. Like, if you are OpenAI or Anthropic who are not public companies that don’t have any credit rating, like, you know, everyone is going to evaluate the risk associated with doing business with those companies. But ultimately, like they don’t have a publicly available credit rating associated with them. How do they go get?

Robinson Meyer:

[41:52] They don’t even have GAAP out. I mean, they don’t have accounting statistics out yet, right? Yeah. Only no open AI and Anthropic’s cash flow from periodic stories, correct?

Peter Freed:

[42:00] And so if you’re a company like that, how do you go get $100 billion to build data center capacity? And the answer is you have to start getting really creative. And that’s where we see, you know, Nvidia throwing some of its credit around to help people go buy their chips. And AMD is doing this and Google is rumored to be doing it. So, you know, there’s it’s this is all financial engineering stuff, which is probably beyond the scope of this podcast. But suffice it to say that people are really working out, trying to figure out how to get the amount of capital that they need to do what they’re proposing to do.

Robinson Meyer:

[42:35] Let’s just lean into this for one more question, because I do want I want to

Robinson Meyer:

[42:40] talk about a few different technologies, and this is an energy and news podcast. But why this matters in a broader sense is when we talk about the scale of organizations that are getting involved, the Saudis, you know, sovereign wealth fund, the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund, insurance companies, I mean, these are the big credit providers, reinsurers, right? These are the big, big wells of money at the basis of the global economy. And when we talk about them getting roped into AI at such a broad scale. We are talking in part, it seems to me, about a situation where

Robinson Meyer:

[43:14] Even though there are various parts of froth in the AI economy, but without anyone feeling like this is a dot-com style story where enormous amounts of wealth are going to be created in a kind of magic way, so you must put all your money in it. Without anyone feeling completely like that or any of the big capital providers feeling completely like that, enough money gets soaked into these projects and has to get involved in these projects just to build them that a huge portion of the economy and business investment and therefore final demand gets tied up in data center projects. And so can you walk us through, from your point of view, like what are the next temporal milestones in the data center story going forward? You know, it sounds like you don’t think power is really ever going to be a bottleneck, partially because of gas. But like what what points this year or in future years will we start to understand, you know, these projects are working or they’re not working, they’re coming together, they’re generating the cash flow they need or they’re not.

Peter Freed:

[44:27] I’m going to answer this question in two ways. One is as like a old energy guy, like how part of the conversation we were talking. And then I’m going to indulge for like half a second in, I live in Menlo Park, California. So like right in the heart of Silicon Valley. Perfect. And I am just like, it’s the only thing that anyone really talks about around here.

Peter Freed:

[44:49] And I do want to give you that answer to that question. So let’s do both. So it’s sort of the traditional energy project finance. Like, how do we think about all of this? Like, you know, I think that there are sufficient pools of capital available to move these projects forward. The question that everyone is going to be looking for is like, is there sufficient revenue quality to justify the amount of money that’s getting put in? And that revenue quality is going to be driven by long-term leases on the data centers and long-term power purchase agreements on the power plants. And I think very likely that people are going to figure enough of that out to move the ball forward at least through 2030. There’s going to have to be some interesting, like particularly The data center industry has historically had at least some speculative development, not the two guys and a dog and a pickup truck that we were talking about earlier, but people doing some amount of work to advance projects to a point that they could begin marketing those projects. And the money associated with that early stage development...

Peter Freed:

[45:49] Was big, but not huge. Now it’s huge. And so I think that’s one of the things that people are still going to have to figure out is like, if you’re a sovereign wealth fund that is used to just really stable returns, because that’s what you do for the citizens of the country whose money you’re managing, you don’t give people billions of dollars to go do speculative development work. So how we address that, I think, is one of the things that people are still trying to figure out. Does it get super disaggregated and you sort of see different pools of capital doing that or, you know, do we just figure out different ways to address that? But that to me is sort of the big question is how do you advance projects to a stage where they can move relatively quickly, but prior to them having some credit-worthy long-term thing locked in? That to me is the thing that the industry is struggling with. And I think people are probably going to figure that out. Now, the like AI-pilled, as they would call it around here, like the AI-pilled answer to that question if you look at claude and claude code so this is like the latest models from anthropic.

Peter Freed:

[46:52] 80% of the code, 80% of the code that is Claude is written by Claude. The expectation by the end of this year is that 90-plus, 95% of the code in Claude will be written by Claude. Which means that we are approaching a point of something that industry hands call recursive self-improvement. Which is basically to say that like the AIs are able to improve themselves and therefore the trajectory and acceleration of improvement will begin to look asymptotic, at least exponential and potentially asymptotic. And the reason that I am particularly interested in this is because all of the work that has happened on AI so far is still not on the giant pieces of infrastructure that we’re constructing right now. So there is really not a gigawatt scale data center. I think the biggest GPU training cluster is probably X.ai is with Colossus and it’s three or 400,000 GPUs. Like no one’s got a million-GPU training cluster. And so if you expect even a linear scaling of performance of the models with the infrastructure that are currently under construction, like one can begin to wrap one’s head around the idea that we will hit this point of like takeoff.

Peter Freed:

[48:11] In which case, all of these things begin becoming better very, very quickly. And maybe data center capacity is actually the limiting factor in terms of how quickly that takes off. That’s what I mean, that’s what people believe, which is why they’re trying to build more of this. So in that universe...

Peter Freed:

[48:28] Who knows what anything looks like, but the ability to run compute at scale will be one of the most significant throttles on that takeoff trajectory. And so I think, you know, I think there is a world in which things look so radically different by 2030 that we can’t even really speculate on what that is. And so that’s the other answer to that question, which is just like, maybe AI figures all this out and we don’t have to worry about it. Like, I don’t know.

Robinson Meyer:

[48:59] And I should say that the day we’re recording this, the market’s down. I mean, the S&P is down 1% because investors have become convinced that were that to happen, it would negatively impact a final demand in the economy rather than positively impact. That being said, let’s assume that it’s 2030 and electricity markets still work roughly like they work. And we might have amazing agents to do all of this stuff, but the actual physical technologies are still binding. And let’s talk about a few technologies that could matter here. The first is batteries. You mentioned that batteries are now being paired with gas to drive reliability. Should we think about flexible data center demand? As some, including current Google employee, Tyler Norris, have talked about as a function of algorithmic, you know, and, you know, actually AI activity flexing up and down. Or at this point, should we think about data center flexibility in the real world as just something created by the batteries you have either on site or behind the substation?

Peter Freed:

[50:01] Yeah, again, there’s nothing technologically infeasible about modulating compute. I just think that generally the economics don’t make sense. I mean, Google has figured out a way to make this make sense, which which actually might mean that other people can figure it out. I think, though, if we can do it synthetically with storage, let’s just say at the fence line and, you know, we can debate what that actually means. That’s probably going to be the fastest, easiest way for most people, like most projects to happen. And again, what does that actually mean? Right. So if we’re if we’re bringing flexibility to the conversation, that means that you are on a system which has sufficient energy in most hours to serve the facility. You’re really addressing a resource adequacy constraint on an August afternoon or a December morning or what have you. And so one of the things that’s actually pretty interesting for the renewables folks is if that flywheel gets going, right, like suddenly we’re effectively addressing these resource adequacy things. We’re using surplus energy, the extra energy that’s available in most hours. If the flywheel gets going, then you need to keep adding more energy to the system. And that’s actually something that is very good for renewables because that will be the fastest, least expensive way to add energy to the system to inject enough surplus energy to keep the like flexibility flywheel moving. Like if you do enough flexibility, flexibility stops working unless you add more energy to the system.

Robinson Meyer:

[51:22] The other way you could do flexibility is through these things that are sometimes called virtual power plants. It’s the idea that you could flex consumer demand household demand up and down you people would get paid to have their air conditioner be a little higher a little lower to run certain processes and energy intensive processes in their house when the grid can withstand it there’s been discussion that ai companies the hyperskillers would be able to pay the amount of money that could actually make these projects feasible is that something you believe will happen and what needs to happen to have a gigawatt of VPPs show up, you know, in, say, the mid-Atlantic or in Texas?

Peter Freed:

[52:02] Yeah, I think it’s possible. Look, I think it’s part of a portfolio. So this bring your own capacity concept, we were talking about it with solar and storage, but there’s no reason why other products couldn’t serve that capacity. And so I think what’s likely to happen is that we will see, you know, consumer demand response or what have you is like a small portion of a portfolio until people get more comfortable with the idea. And then maybe it’ll grow. And ultimately, hopefully the market just says, whatever the most cost-efficient way to provide this particular capacity product at this time, like we’ll do that. So I think, you know, hopefully we’ll see.

Robinson Meyer:

[52:41] Which market?

Peter Freed:

[52:42] Well, I mean, that’s the other question.

Robinson Meyer:

[52:44] Right? In ERCOT, I bet the right market would show up. And PJM, I don’t know.

Peter Freed:

[52:47] It’s hard to say.

Robinson Meyer:

[52:48] I’m just in rapid fire now. One of the things I’m hearing from you is that behind the meter gas, is going to bridge to 2030. Data centers are going to have the electricity they need via behind the meter gas and batteries, and it’s going to get to 2030, at which point more gas turbine, you know, power plant scale, gas turbine capacity comes online. Do you see a role for other technologies at that point? I mean, that’s when I would think about like geothermal become salient to this kind of this kind of story.

Peter Freed:

[53:19] Yeah, I think the broad perception is that post 2030, the aperture of opportunity is wider. And I would agree with that with the following caveat. It won’t be any wider unless people are working on it now. And so that is one of the, like, we’ve been talking about this since 2024. And I wouldn’t necessarily say I’ve seen like the intensive level of investment and preparing for a post 2030 world in the last two years. So, you know, we’ve seen some cool stuff on geothermal. We’ve seen some interesting nuclear stuff. But I wouldn’t necessarily say that like a groundswell of investment and innovation that’s required to have a radically different slate of generating technologies in a post 2030, like I’m not seeing that. And so if the world is going to look really different or we’re going to see a lot more opportunity post 2030, I think people need to be doing more.

Robinson Meyer:

[54:12] What’s the one thing?

Robinson Meyer:

[54:15] Public policy or investment decision that would need to happen to slow down or change the makeup of the huge amount of behind the meter gas that it seems like we’re about to get across the country like if you were a democratic policy maker or an energy policy maker someone who wants

Peter Freed:

[54:35] I mean I’m a I’m a carrots not sticks guy, Rob, so I think rather than slowing that down, I would think about speeding the other stuff up and no great surprise. It’s figuring out how to get more transmission built, just permitting reform. It’s stuff that we’ve been aware of for a long time. And we are now seeing significant levels of government subsidy kind of going into all kinds of different things and in ways that maybe we haven’t seen before. So you could imagine a lot of what we’ve seen in the nuclear industry is probably going to help it have a moment that it wouldn’t have had a couple of years ago.

Robinson Meyer:

[55:10] That’s kind of what I’m asking. Is it that there needs to be investment in these public investment or either permitting reform for transmission or some kind of fixed transmission build out or nuclear build out in order to just like, if you care about emissions, this is what maybe needs to happen. There’s a whole set of questions here that I want to hit that we’re right at time for. But if you had advice to data center developers at this moment, renewable developers for a long time have been in a world where Our communities can give them all sorts of feedback. For data center developers, what separates a good developer from a bad developer? What should good data center developers be doing and what do they look like?

Peter Freed:

[55:47] Yeah, I mean, look, at the end of the day, it’s getting engaged with communities, and it has to be that. And that’s always been the case. And people are just slowly getting better at it.

Robinson Meyer:

[55:56] Great. Well, we’re going to have to leave it there. Peter Freed, thank you so much for joining us. It was great, as always.

Peter Freed:

[56:00] Thank you for having me. A real pleasure.

Robinson Meyer:

[56:02] Thank you so much for listening. If you enjoyed this conversation or conversations like it, please subscribe to Shift Key. In any podcast app you use, you can also find us at heatmap.news. And remember, if you want to keep following how data centers are reshaping the energy transition, because they’re doing quite a bit, then that is the work we do every day at Heatmap in our newsroom and also in our pro team. Our pro team tracks where energy and data center projects move forward, where they get delayed or canceled, and how community response shapes outcomes. You can find the link to that in the chat. If you’re interested in learning more about the software, visit heatmap.news/pro. That’s heatmap.news/pro. If you enjoyed Shift Key, then leave us a review or send this episode to your friends. You can follow me on X or Bluesky or LinkedIn, all of the above, under my name, Robinson Meyer. Shift Key is a production of Heatmap News. Our editors are Jillian Goodman and Nico Lauricella. Multimedia editing and audio engineering is by Jacob Lambert and by Nick Woodbury. Our music is by Adam Kromelow. Thanks so much for listening and see you next week.

The long-duration energy storage startup is scaling up fast, but as Form CEO Mateo Jaramillo told Heatmap, “There aren’t any shortcuts.”

Long-duration energy storage startup Form Energy on Tuesday announced plans to deploy what would be the largest battery in the world by energy capacity: an iron-air system capable of delivering 300 megawatts of power at once while storing 30 gigawatt-hours of energy, enabling continuous discharge for 100 hours straight. The project, developed in partnership with the utility Xcel Energy, will help power a new Google data center in Minnesota that will also be supplied by 1,400 megawatts of wind generation and 200 megawatts of solar power.

Form expects to begin delivering batteries to the data center in 2028. The systems will be manufactured at the company’s West Virginia factory, which is expected to reach an annual production capacity of 500 megawatts by the end of that year.

The Google deal represents a significant play for scale from the startup, which has raised about $1.2 billion to date. By comparison, Form’s first commercial deployment with Great River Energy — slated to become fully operational this year — is designed to store just 150 megawatt-hours of energy.

Google will cover all the costs of the clean energy generation, battery storage, and related grid infrastructure for the new data center through a contract structure it developed called a Clean Energy Accelerator Charge, which ensures that regional ratepayers aren’t left footing the bill. While Form isn’t disclosing the expected cost of this battery deployment, CEO Mateo Jaramillo told me that the company remains committed to achieving a fully installed system cost below $20 per kilowatt-hour by the end of the decade.

I spoke with Jaramillo about Form’s latest announcement, what it’s been up to over the past several years, and the operational and technical improvements that have allowed it to pursue a project of this scale despite the fact that it’s yet to deploy commercial projects anywhere near this size. This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Tell me about your history with Xcel Energy?

They know us extremely well. They’ve been inside our operation for, I think, five years now. So they’ve tracked us every single step of the way. They’re very familiar with the technology, with the team, with the progress, so they were ready to sign a deal that is the next scale larger even though we’ve yet to deliver on the very first [smaller scale] ones. Those are coming shortly, but they wanted to get going on hitting the scale-up as soon as possible.

What have you been working on over the past year that’s allowed you to move to this larger scale so quickly?

We’ve been fairly quiet about it, but we did deploy a first generation of the product last year with Great River Energy, albeit in relatively limited volumes. To get there we had to produce 100,000 electrodes, roughly. So it’s like 60 miles worth of material going through the factory, to prove to ourselves — and obviously to our customers — that we had process control. One of the major trap doors for any battery company is manufacturing at scale — until you do that, you can’t really say you understand your chemistry, frankly. And so that’s what we did over the last 18 months. It was arduous and challenging sometimes, but there aren’t any shortcuts. Prototypes are easy, and scale is hard.

So that was the work that we had to get through, which then informed a second generation design that we kicked off last summer and we’re now building today in the factory, doing the first phase of testing — design validation testing, production validation testing — before we start to really ramp up later this summer.

How are your second-generation battery cells an improvement over the first?