You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

It took the market about a week to catch up to the fact that the Chinese artificial intelligence firm DeepSeek had released an open-source AI model that rivaled those from prominent U.S. companies such as OpenAI and Anthropic — and that, most importantly, it had managed to do so much more cheaply and efficiently than its domestic competitors. The news cratered not only tech stocks such as Nvidia, but energy stocks, as well, leading to assumptions that investors thought more-energy efficient AI would reduce energy demand in the sector overall.

But will it really? While some in climate world assumed the same and celebrated the seemingly good news, many venture capitalists, AI proponents, and analysts quickly arrived at essentially the opposite conclusion — that cheaper AI will only lead to greater demand for AI. The resulting unfettered proliferation of the technology across a wide array of industries could thus negate the energy efficiency gains, ultimately leading to a substantial net increase in data center power demand overall.

“With cost destruction comes proliferation,” Susan Su, a climate investor at the venture capital firm Toba Capital, told me. “Plus the fact that it’s open source, I think, is a really, really big deal. It puts the power to expand and to deploy and to proliferate into billions of hands.”

If you’ve seen lots of chitchat about Jevons paradox of late, that’s basically what this line of thinking boils down to. After Microsoft’s CEO Satya Nadella responded to DeepSeek mania by posting the Wikipedia page for this 19th century economic theory on X, many (myself included) got a quick crash course on its origins. The idea is that as technical efficiencies of the Victorian era made burning coal cheaper, demand for — and thus consumption of — coal actually increased.

While this is a distinct possibility in the AI space, it’s by no means a guarantee. “This is very much, I think, an open question,“ energy expert Nat Bullard told me, with regards to whether DeepSeek-type models will spur a reduction or increase in energy demand. “I sort of lean in both directions at once.” Formerly the chief content officer at BloombergNEF and current co-founder of the AI startup Halcyon, a search and information platform for energy professionals, Bullard is personally excited for the greater efficiencies and optionality that new AI models can bring to his business.

But he warns that just because DeepSeek was cheap to train — the company claims it cost about $5.5 million, while domestic models cost hundreds of millions or even billions — doesn’t mean that it’s cheap or energy-efficient to operate. “Training more efficiently does not necessarily mean that you can run it that much more efficiently,” Bullard told me. When a large language model answers a question or provides any type of output, it’s said to be making an “inference.” And as Bullard explains, “That may mean, as we move into an era of more and more inference and not just training, then the [energy] impacts could be rather muted.”

DeepSeek-R1, the name for the model that caused the investor freakout, is also a newer type of LLM that uses more energy in general. Up until literally a few days ago, when OpenAI released o3-mini for free, most casual users were probably interacting with so-called “pretrained” AI models. Fed on gobs of internet text, these LLMs spit out answers based primarily on prediction and pattern recognition. DeepSeek released a model like this, called V3, in September. But last year, more advanced “reasoning” models, which can “think,” in some sense, started blowing up. These models — which include o3-mini, the latest version of Anthropic’s Claude, and the now infamous DeepSeek-R1 — have the ability to try out different strategies to arrive at the correct answer, recognize their mistakes, and improve their outputs, allowing for significant advancements in areas such as math and coding.

But all that artificial reasoning eats up a lot of energy. As Sasha Luccioni, the AI and climate lead at Hugging Face, which makes an open-source platform for AI projects, wrote on LinkedIn, “To set things clear about DeepSeek + sustainability: (it seems that) training is much shorter/cheaper/more efficient than traditional LLMs, *but* inference is longer/more expensive/less efficient because of the chain of thought aspect.” Chain of thought refers to the reasoning process these newer models undertake. Luccioni wrote that she’s currently working to evaluate the energy efficiency of both the DeepSeek V3 and R1 models.

Another factor that could influence energy demand is how fast domestic companies respond to the DeepSeek breakthrough with their own new and improved models. Amy Francetic, co-founder at Buoyant Ventures, doesn’t think we’ll have to wait long. “One effect of DeepSeek is that it will highly motivate all of the large LLMs in the U.S. to go faster,” she told me. And because a lot of the big players are fundamentally constrained by energy availability, she’s crossing her fingers that this means they’ll work smarter, not harder. “Hopefully it causes them to find these similar efficiencies rather than just, you know, pouring more gasoline into a less fuel-efficient vehicle.”

In her recent Substack post, Su described three possible futures when it comes to AI’s role in the clean energy transition. The ideal is that AI demand scales slowly enough that nuclear and renewables scale with it. The least hopeful is that immediate, exponential growth in AI demand leads to a similar expansion of fossil fuels, locking in new dirty infrastructure for decades. “I think that's already been happening,” Su told me. And then there’s the techno-optimist scenario, linked to figures like Sam Altman, which Su doesn’t put much stock in — that AI “drives the energy revolution” by helping to create new energy technologies and efficiencies that more than offset the attendant increase in energy demand.

Which scenario predominates could also depend upon whether greater efficiencies, combined with the adoption of AI by smaller, more shallow-pocketed companies, leads to a change in the scale of data centers. “There’s going to be a lot more people using AI. So maybe that means we don’t need these huge, gigawatt data centers. Maybe we need a lot more smaller, megawatt-size data centers,” Laura Katzman, a principal at Buoyant Ventures, told me. Katzman has conducted research for the firm on data center decarbonization.

Smaller data centers with a subsequently smaller energy footprint could pair well with renewable-powered microgrids, which are less practical and economically feasible for hyperscalers. That could be a big win for solar and wind plus battery storage, Katzman explained, but a boondoggle for companies such as Microsoft, which has famously committed to re-opening Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island nuclear plant to power its data centers. “Because of DeepSeek, the expected price of compute probably doesn’t justify now turning back on some of these nuclear plants, or these other high-cost energy sources,” Katzman told me.

Lastly, it remains to be seen what nascent applications cheaper models will open up. “If somebody, say, in the Philippines or Vietnam has an interest in applying this to their own decarbonization challenge, what would they come up with?” Bullard pondered. “I don’t yet know what people would do with greater capability and lower costs and a different set of problems to solve for. And that’s really exciting to me.”

But even if the AI pessimists are right, and these newer models don’t make AI ubiquitously useful for applications from new drug discovery to easier regulatory filing, Su told me that in a certain sense, it doesn't matter much. “If there was a possibility that somebody had this type of power, and you could have it too, would you sit on the couch? Or would you arms race them? I think that is going to drive energy demand, irrespective of end utility.”

As Su told me, “I do not think there’s actually a saturation point for this.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

On the solar siege, New York’s climate law, and radioactive data center

Current conditions: A rain storm set to dump 2 inches of rain across Alabama, Tennessee, Georgia, and the Carolinas will quench drought-parched woodlands, tempering mounting wildfire risk • The soil on New Zealand’s North Island is facing what the national forecast called a “significant moisture deficit” after a prolonged drought • Temperatures in Odessa, Texas, are as much as 20 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than average.

For all its willingness to share in the hype around as-yet-unbuilt small modular reactors and microreactors, the Trump administration has long endorsed what I like to call reactor realism. By that, I mean it embraces the need to keep building more of the same kind of large-scale pressurized water reactors we know how to construct and operate while supporting the development and deployment of new technologies. In his flurry of executive orders on nuclear power last May, President Donald Trump directed the Department of Energy to “prioritize work with the nuclear energy industry to facilitate” 5 gigawatts of power uprates to existing reactors “and have 10 new large reactors with complete designs under construction by 2030.” The record $26 billion loan the agency’s in-house lender — the Loan Programs Office, recently renamed the Office of Energy Dominance Financing — gave to Southern Company this week to cover uprates will fulfill the first part of the order. Now the second part is getting real. In a scoop on Thursday, Heatmap’s Robinson Meyer reported that the Energy Department has started taking meetings with utilities and developers of what he said “would almost certainly be AP1000s, a third-generation reactor produced by Westinghouse capable of producing up to 1.1 gigawatts of electricity per unit.”

Reactor realism includes keeping existing plants running, so notch this as yet more progress: Diablo Canyon, the last nuclear station left in California, just cleared the final state permitting hurdle to staying open until 2030, and possibly longer. The Central Coast Water Board voted unanimously on Thursday to give the state’s last nuclear plant a discharge permit and water quality certification. In a post on LinkedIn, Paris Ortiz-Wines, a pro-nuclear campaigner who helped pass a 2022 law that averted the planned 2025 closure of Diablo Canyon, said “70% of public comments were in full support — from Central Valley agricultural associations, the local Chamber of Commerce, Dignity Health, the IBEW union, district supervisors, marine meteorologists, and local pro-nuclear organizations.” Starting in 2021, she said, she attended every hearing on the bill that saved the plant. “Back then, I knew every single pro-nuclear voice testifying,” she wrote. “Now? I’m meeting new ones every hearing.”

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. It was a year of record solar deployments, it was a year of canceled solar megaprojects, choked-off permits, and desperate industry pleas to Congress for help. But the solar industry’s political clouds may be parting. The Department of the Interior is reviewing at least 20 commercial-scale projects that E&E News reported had “languished in the permitting pipeline” since Trump returned to office. “That includes a package of six utility-scale projects given the green light Friday by Interior Secretary Doug Burgum to resume active reviews, such as the massive Esmeralda Energy Center in Nevada,” the newswire reported, citing three anonymous career officials at the agency.

Heatmap’s Jael Holzman broke the news that the project, also known as Esmeralda 7, had been canceled in October. At the time, NextEra, one of the project’s developers, told her that it was “committed to pursuing our project’s comprehensive environmental analysis by working closely with the Bureau of Land Management.” That persistence has apparently paid off. In a post on X linking to the article, Morgan Lyons, the senior spokesperson at the Solar Energy Industries Association, called the change “quite a tone shift” with the eyes emoji. GOP voters overwhelmingly support solar power, a recent poll commissioned by the panel manufacturer First Solar found. The MAGA coalition has some increasingly prominent fans. As I have covered in the newsletter, Katie Miller, the right-wing influencer and wife of Trump consigliere Stephen Miller, has become a vocal proponent of competing with China on solar and batteries.

Get Heatmap AM directly in your inbox every morning:

MP Materials operates the only active rare earths mine in the United States at California’s Mountain Pass. Now the company, of which the federal government became the largest shareholder in a landmark deal Trump brokered earlier this year, is planning a move downstream in the rare earths pipeline. As part of its partnership with the Department of Defense, MP Materials plans to invest more than $1 billion into a manufacturing campus in Northlake, Texas, dedicated to making the rare earth magnets needed for modern military hardware and electric vehicles. Dubbed 10X, the campus is expected to come online in 2028, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

New York’s rural-urban divide already maps onto energy politics as tensions mount between the places with enough land to build solar and wind farms and the metropolis with rising demand for power from those panels and turbines. Keeping the state’s landmark climate law in place and requiring New York to generate the vast majority of its power from renewables by 2040 may only widen the split. That’s the obvious takeaway from data from the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority. In a memo sent Thursday to Governor Kathy Hochul on the “likely costs of” complying with the law as it stands, NYSERDA warned that the statute will increase the cost of heating oil and natural gas. Upstate households that depend on fossil fuels could face hikes “in excess of $4,000 a year,” while New York City residents would see annual costs spike by $2,300. “Only a portion of these costs could be offset by current policy design,” read the memo, a copy of which City & State reporter Rebecca C. Lewis posted on X.

Last fall, this publication’s energy intelligence unit Heatmap Pro commissioned a nationwide survey asking thousands of American voters: “Would you support or oppose a data center being built near where you live?” Net support came out to +2%, with 44% in support and 42% opposed. Earlier this month, the pollster Embold Research ran the exact same question by another 2,091 registered voters across the country. The shift in the results, which I wrote about here, is staggering. This time just 28% said they would support or strongly support a data center that houses “servers that power the internet, apps, and artificial intelligence” in their neighborhood, while 52% said they would oppose or strongly oppose it. That’s a net support of -24% — a 26-point drop in just a few months.

Among the more interesting results was the fact that the biggest partisan gap was between rural and urban Republicans, with the latter showing greater support than any other faction. When I asked Emmet Penney at the right-leaning Foundation for American Innovation to make sense of that for me, he said data centers stoke a “fear of bigness” in a way that compares to past public attitudes on nuclear power.

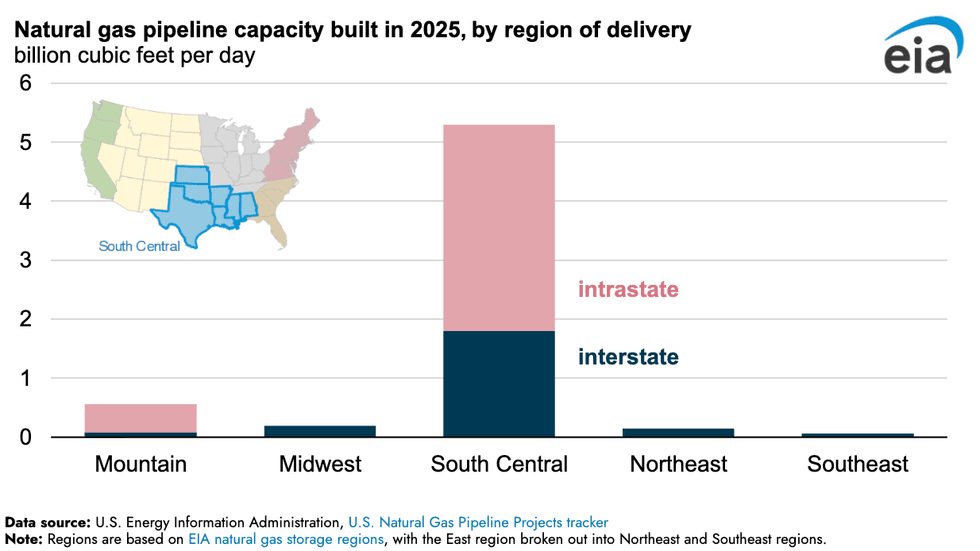

Gas pipeline construction absolutely boomed last year in one specific region of the U.S. Spanning Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, the so-called South Central bloc saw a dramatic spike in intrastate natural gas pipelines, more than all other regions combined, per new Energy Information Administration data. It’s no mystery as to why. The buildout of liquified natural gas export terminals along the Gulf coast needs conduits to carry fuel from the fracking fields as far west as the Texas Permian.

Rob sits down with Jane Flegal, an expert on all things emissions policy, to dissect the new electricity price agenda.

As electricity affordability has risen in the public consciousness, so too has it gone up the priority list for climate groups — although many of their proposals are merely repackaged talking points from past political cycles. But are there risks of talking about affordability so much, and could it distract us from the real issues with the power system?

Rob is joined by Jane Flegal, a senior fellow at the Searchlight Institute and the States Forum. Flegal was the former senior director for industrial emissions at the White House Office of Domestic Climate Policy, and she has worked on climate policy at Stripe. She was recently executive director of the Blue Horizons Foundation.

Shift Key is hosted by Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Here is an excerpt from their conversation:

Robinson Meyer: What’s interesting is the scarcity model is driven by the fact that ultimately rate payers that is utility customers are where the buck stops, and so state regulators don’t want utilities to overbuild for a given moment because ultimately it is utility customers — it’s people who pay their power bills — who will bear the burden of a utility overbuilding. In some ways, the entire restructured electricity market system, the entire shift to electricity markets in the 90s and aughts, was because of this belief that utilities were overbuilding.

And what’s been funny is that, what, we started restructuring markets around the year 2000. For about five or six or seven years. Wall Street was willing to finance new electricity. I mean, I hear two stories here — basically it’s another place where I hear two stories, and I think where there’s a lot of disagreement about the path forward on electricity policy, in that I’ve heard a story that, basically, electricity restructuring starts in the late 90s you know year 2000, and for five years, Wall Street is willing to finance new power investment based entirely on price risk based entirely on the idea that market prices for electricity will go up. Then three things happen: The Great Recession, number one, wipes out investment, wipes out some future demand.

Number two, fracking. Power prices tumble, and a bunch of plays that people had invested in, including then advanced nuclear, are totally out of the money suddenly. Number three, we get electricity demand growth plateaus, right? So for 15 years, electricity demand plateaus. We don’t need to finance investments into the power grid anymore. This whole question of, can you do it on the back of price risk? goes away because electricity demand is basically flat, and different kinds of generation are competing over shares and gas is so cheap that it’s just whittling away.

Jane Flegal: But this is why that paradigm needs to change yet again. Like ,we need to pivot to like a growth model where, and I’m not, again —

Meyer: I think what’s interesting, though, is that Texas is the other counterexample here. Because Texas has had robust load growth for years, and a lot of investment in power production in Texas is financed off price risk, is financed off the assumption that prices will go up. Now, it’s also financed off the back of the fact that in Texas, there are a lot of rules and it’s a very clear structure around finding firm offtake for your powers. You can find a customer who’s going to buy 50% of your power, and that means that you feel confident in your investment. And then the other 50% of your generation capacity feeds into ERCOT. But in some ways, the transition that feels disruptive right now is not only a transition like market structure, but also like the assumptions of market participants about what electricity prices will be in the future.

Flegal: Yeah, and we may need some like backstop. I hear the concerns about the risks of laying early capital risks basically on rate payers in the frame of growth rather than scarcity. But I guess my argument is just there’s ways to deal with that. Like we could come up with creative ways to think about dealing with that. And I’m not seeing enough ideation in that space, which — I would like, again, a call for papers, I guess — that I would really like to get a better handle on.

The other thing that we haven’t talked about, but that I do think, you know, the States Forum, where I’m now a senior fellow, I wrote a piece for them on electricity affordability several months ago now. But one of the things that doesn’t get that much attention is just like getting BS off of bills, basically. So there’s like the rate question, but then there’s the like, what’s in a bill? And like, what, what should or should not be in a bill? And in truth, you know, we’ve got a lot of social programs basically that are being funded by the rate base and not the tax base. And I think there are just like open questions about this — whether it’s, you know, wildfire in California, which I think everyone recognizes is a big challenge, or it’s efficiency or electrification or renewable mandates in blue states. There are a bunch of these things and it’s sort of like there are so few things you can do in the very near term to constrain rate increases for the reasons we’ve discussed.

You can find a full transcript of the episode here.

Mentioned:

Cheap and Abundant Electricity Is Good, by Jane Flegal

From Heatmap: Will Virtual Power Plants Ever Really Be a Thing?

Previously on Shift Key: How California Broke Its Electricity Bills and How Texas Could Destroy Its Electricity Market

This episode of Shift Key is sponsored by …

Accelerate your clean energy career with Yale’s online certificate programs. Explore the 10-month Financing and Deploying Clean Energy program or the 5-month Clean and Equitable Energy Development program. Use referral code HeatMap26 and get your application in by the priority deadline for $500 off tuition to one of Yale’s online certificate programs in clean energy. Learn more at cbey.yale.edu/online-learning-opportunities.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.

This transcript has been automatically generated.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Robinson Meyer:

[1:26] It is Friday, February 27th. I’m Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News. Since Zohran Mamdani’s campaign in New York City last year, the watchword of progressive campaigns everywhere has been affordability. And now lots of climate groups are getting in on the act too and talking about affordability, inflation, particularly electricity affordability. And this question of, are power bills too expensive and what can be done to bring them down? And I get it. Listen, there were moments last year where electricity prices were increasing twice as fast as inflation, and that was before the tidal wave of new data centers came online. But is it a mistake to anchor climate politics, this big global issue, so tightly to these questions of domestic electricity affordability? Well, joining us today to talk about it is Jane Flagle. She’s done everything. She’s been everywhere, and she’s someone I always like to talk to about the wide world of climate and energy policy. In 2021 and 2022, she was Senior Director for Industrial Emissions at the White House Office of Domestic Climate Policy. She’s since then worked in climate policy at Stripe. She was recently executive director at the Blue Horizons Foundation, and she’s now a senior fellow at the Searchlight Institute and the States Forum. Jane and I have a big fun conversation on this show about two different philosophies of how to run the power grid, what we can learn from Texas and France, at least in the rest of the United States, and whether affordability is the wrong way to talk about climate politics. All that and more. It’s all coming up on Shift Key, a podcast about decarbonization and the shift away from fossil fuels.

Robinson Meyer:

[2:54] Jane, welcome to Shift Key.

Jane Flegal:

[2:56] Thanks so much for having me, Robinson. Great to be here again.

Robinson Meyer:

[2:59] Jane, you’re always someone who I like to talk to who’s thinking about different topics in climate advocacy. We always check in. Now we’re doing it for Shift Key. I’m going to just start off by asking, over the past six months, in some ways since the Mamdani campaign in New York, there has been this massive stampede of advocacy dollars, of progressive communications, of climate communications to talking about affordability. And that’s had some interesting secondhand byproducts. We can talk about how that happened. But do you think it’s a mistake to focus on electricity affordability as much as everyone is now focusing on electricity affordability?

Jane Flegal:

[3:37] Yeah, it’s a good question. I mean, in a way, it’s like it’s about time that the climate community focus more squarely on electricity affordability, not least because, all of our visions for decarbonization depend on rapid electrification of the entire economy, which means that every other sector of the economy then becomes a consumer of electricity. And quite obviously, that won’t happen if the prices of electricity are too high. So A, I think some people have been claiming to be advancing affordability in the climate domain for a long time, but now everyone’s doing affordability.

Robinson Meyer:

[4:17] Everything is an affordability policy.

Jane Flegal:

[4:19] Even if the policy is exactly the same as it was before, before the articulation of affordability as the rationale. And so because I do think that like it is an imperative for like a politically sustainable transition to an electrified economy, and not just an electrified economy, one where electricity is powering significant economic growth and new industries, leaving aside AI, right? This would be a huge challenge for our country.

Robinson Meyer:

[4:48] Right. At the same time, we’re talking about electricity affordability. There’s all this attention devoted to load growth and the fact that electricity demand is increasing. And that would have been happening now anyway, even if artificial intelligence remained a glimmer in Dario’s eye or Sam Altman’s eye, we would still be beginning to grapple with electricity demand growth again, because the reason we haven’t had growth since 2005 is because everyone was transferring from incandescent lights to compact fluorescent lights. Then we had a recession and then everyone transferred from compact fluorescents to LEDs. And now LEDs are, they’re probably in more than half of fixtures across the country. And so we kind of got all the juice we could out of that particular efficiency squeeze. And so we’d be seeing load growth anyway.

Jane Flegal:

[5:36] Totally. And if we are lucky, we will see electricity load growth, right? Both for our climate objectives and for like the functioning of our economy. Like load growth is good. Like it is good. Now, one can litigate the social value of particular industries or the behavior of particular industries, whatever. But as a matter of energy policy, That is just true. So for that reason, I’m sort of like, it is an imperative for all of us who care about climate to make sure that electricity is affordable so that we can electrify everything else. It is also critical that we have a lot of affordable electricity to electrify everything else. And I guess where I feel a little tied up in knots myself right now is like the conversation about what affordability looks like is highly focused, and narrowly focused, I would argue, on this like very short-term acute concern about meeting data center demand and like making more efficient use of the resources we already have to meet that demand. If we weren’t imagining a world with load growth at the scale we want to imagine that might be fine but like.

Jane Flegal:

[6:47] No amount of efficiency, of demand response, of getting more out of the grid.

Jane Flegal:

[6:52] We cannot like VPP our way to 2x-ing the grid in a decade and a half. You know what I mean? So like we are going to have to find a way to thread the needle here between cost constraining measures in the near term, including getting more of what we’ve already built, with the like actual very real imperative to build a lot more stuff very quickly.

Robinson Meyer:

[7:14] Let me go back and just gloss some of what you said, because you said initialisms that I think are familiar to you and me that I would imagine are familiar to many of our listeners, but perhaps not all of them. I believe the big one was VPPs, which are virtual power plants. A virtual power plant, as you could read on Heatmap, we’ll stick in the show notes, and my colleague Katie Brigham’s recent story, is a set of residential rooftop solar panels, residential batteries, residential HVAC systems, residential appliances, maybe EV charging, all strung together in a big software organized system that can respond to either demand fluctuations in the grid or price action in the grid to make sure that all those things are either sucking up power from the grid when it’s cheap or when clean energy is abundant or putting it back in the grid or at least reducing the amount of energy that homes are pulling from the grid during moments of peak stress. And I think what you’re implying is that

Robinson Meyer:

[8:16] We are watching a moment in the electricity sector where gigawatt scale facilities are beginning to come online, where we are going to need gigawatts of new demand to meet growth. And the playbook that is being deployed is one focused perhaps on making sure that we get the most out of all the generating assets, the power plants, the poles and wires, the transformers that are already out there to basically shave those moments of peak demand so that they don’t stress the existing system. And you’re saying, yeah, that’s important. But for the amount of growth that we’re seeing and for the amount of growth that we need to see, we actually need to be ready not just to shave those moments of peak demand, but to grow the grid at an infrastructural level and prepare for serious, serious load growth, which may be the tools that we’re using, such as and Trying to get homes in these virtual power plants, trying to get people to time their EV charging, either through incentives or through software, so that it doesn’t stress the grid at its most congested moments is like not enough to meet the challenge that we’re seeing.

Jane Flegal:

[9:29] Yeah, I think that that’s right. And that’s not to be dismissive of that set of interventions. I just think it is potentially necessary. Although, to be honest, I think there are real questions about the barriers to scale for some of these things. Like VPPs do not exist at the scale that we are imagining them to exist at in the same way that like small modular reactors don’t, right? Like these are all kind of imagined future states. And so like I just get anxiety about betting the climate on like one of those things.

Robinson Meyer:

[9:59] By the time we release this episode, we’ll put out this conversation I just had with Peter Freed, his former head of energy policy at Meta. And one thing he was saying is that all these data centers are basically not preparing to receive power from the grid until 2030. And so they’re all building giant on-site gas generation, basically with batteries to prepare just to be able to operate until they can get a grid hookup. Which number one suggests that a moratorium on data center grid connections would not be a very useful policy because that just means they’re going to burn 100 gas rather than whatever you can public policy your way into making the local grid but number two actually does to me, though, suggest that this set of tools that might be coming on online in 2030, maybe large scale VPPs, but also next generation nuclear, or at least a new fleet of current generation nuclear reactors.

Jane Flegal:

[10:55] Or geothermal.

Robinson Meyer:

[10:56] Or geothermal. Suddenly those tools become things we should be thinking about, because it sounds like 2030 is actually kind of when we will begin to need these tools since data centers

Jane Flegal:

[11:06] Have evidently decided. That really bums me out. That really bums me out. And like, it also goes to the affordability question, right? Like the notion that we wouldn’t take advantage of near-term demand and near-term demand that seems quite willing to pay for energy, that we can’t find some way to like leverage that to do the kind of supply side investments we need to have without having it all be on the backs of rate payers. It actually could be an opportunity, but instead it’s all viewed as downside risk. We could be not just expanding the denominator, but redistributing who actually is paying for this stuff outside of just the rate payers if we were creative here, instead of just being moratorium on great connections or whatever. That’s part of the problem that I’m frustrated by right now.

Jane Flegal:

[11:55] I just think we need much more creative thinking on this set of issues.

Robinson Meyer:

[11:59] So stipulated that this conversation is not so you can announce your big policy playbook of tools and policies that will actually solve these problems, but what kind of policies are you thinking about that would solve these problems and that you would contrast to the demand-shaving, efficiency-focused policies that are maybe already out there?

Jane Flegal:

[12:19] I am really trying to think about this more seriously right now, and people smarter than me should actually be in charge of figuring this out. But I think one thing is like a.

Robinson Meyer:

[12:29] Call for papers. This is a call for papers.

Jane Flegal:

[12:31] Someone please, someone please write these papers. I think one thing is like, We need to lower the cost of capital for grid scale projects, right? And so like, I think this question of how do you better use public financing, like you don’t necessarily have to go to like full throated public ownership of grid and grid assets, but like some kind of like, how do we better leverage the public to try to get whoever, utilities or developers or whatever, to use more cheap debt and less equity. To finance energy projects, I think is like a really underexplored set of ideas. And I would love to see more creative thinking on that set of issues, like whether it’s bonding or I don’t know, I think there’s like a bunch of things that you could do there. And then another thing is just like much more effective grid planning. And the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has this like order 1920.

Jane Flegal:

[13:31] Which is meant to force entities to not just plan for like the lowest possible load growth scenario in the next two years, but to plan over much longer time horizons and to plan for a range of scenarios, including like a high electrification scenario. I think improvements to grid planning, whether that FERC 1920 stuff can actually have teeth, whether it actually matters, I think is an open question, but it could be really powerful. And like tools in that category of grid planning for growth, not just grid planning for flat demand, which is what we’ve been doing for more than a decade, I think is really important. The other category of things is what a lot of people talk about, which is.

Jane Flegal:

[14:17] Citing and permitting challenges like we do actually genuinely have to do have to do permitting reform i continue to perhaps foolishly be bullish on federal permitting reform i think if you could get a federal deal that dealt with sort of what people are now calling permitting certainty you know the ability for the executive to like muck around and permits willy-nilly basically and something on transmission, like changes to the Federal Power Act that might help with this transmission planning and financing issue, and changes to NEPA and potentially the Clean Water Act. That, to me, would be very helpful.

Robinson Meyer:

[14:56] There’s something in there, too, that I want to just call out because I’ve been thinking about it as well, which is I think we made a mistake when we called the current House and Senate energy bill permitting reform and then grouped transmission under permitting reform, because permitting reform is primarily about things like the National Environmental Policy Act, about the kind of procedures you have to step through in order to build a kind of large-scale infrastructure project, who has the ability to approve those large-scale infrastructure projects. And for long-distance, large-scale transmission, there are key permitting barriers. However, there’s another part of the transmission package in front of the House and Senate, which is really not about permitting at all, and is usually called cost allocation. And I just want to emphasize that cost allocation is so important. Right now, if there are two utilities, even if they want to build a power line between their territories, they will have to figure out how to divide up the costs on a completely ad hoc basis, which is not how we fund other kinds of infrastructure.

Robinson Meyer:

[15:59] In a grid region. And what that means is that we actually don’t know the amount of transmission that would instantly finance itself in the country, were these rules to exist. Because with the lack of rules, nobody can go out and do a study on what transmission would be economical that we don’t have right now. Because we don’t know how the cost would be divided up. There’s no playbook on how that should work. And so I just want to emphasize that.

Jane Flegal:

[16:28] I think that’s totally right because the transmission section is really much more about like Federal Power Act reform than it is about NEPA, right? Then there’s like a separate set of issues around NEPA. And then like the last thing that I’ll mention on some of these like cost mitigation strategies is supply chain dynamics, which continue to be in a way that I always find surprising because I forget that we live in a physical world even after COVID. I’m like, oh, right, like, no one can get transformers. And like, I still am confused about whether anyone can or cannot get a gas turbine. And then certainly the tariffs and the foreign entity of concern requirements, there are all these ways in which we’re mucking around in like, the costs of our infrastructure for energy and other things like the tariffs are bad for energy infrastructure of all kinds, whether it’s oil and gas or clean energy. So I mean, those are all things that I think are worthy of further exploration for sure.

Robinson Meyer:

[19:04] I feel like there are two big schools of thought on utility matters right now. And I’ve been grouping them as ERCOT or EDF. So ERCOT is the Texas grid. It has an extremely competitive market-driven approach. Famously, its biggest market is this energy market. It allows prices to get extremely high in that market, thousands of dollars per megawatt, in order to make that market clear. It has an interesting structure where it has both a spot market for electricity on the moment-to-moment basis and also a robust set of rules governing two-party arrangements in ERCOT. It’s a very competition-based form of structuring a grid. Then you have EDF, which is a French utility that built a lot of nuclear power plants at the same time in the 1970s and 1980s and did so eventually very cheaply and now supplies extremely cheap and carbon-free electricity to the nation of France.

Robinson Meyer:

[20:11] I feel like people tend to go one or the other way when they are thinking about where the grid should go. There’s a set of ideas that say, actually, utilities should only control the distribution grid. And then you should be able to choose a retailer of electricity to sell you electricity, like you can choose a retailer of electricity in Texas. And some people say, no, no, no, actually, we want utilities to be big, to be full monopolies. We need to regulate them differently perhaps, but we want them to be able to embark on these big capital projects that where they outlay huge amounts of money on a forward going basis to make sure that a service area can meet its electricity demand for a decade or two decades to come, much like France did in the 1970s with its giant nuclear power plant buildout. And I would say there’s some evidence on the latter side in that the only There were a number of different offshore wind projects that were undertaken

Robinson Meyer:

[21:10] during the Biden administration. And the one that got to completion relatively early was this Dominion offshore wind project in Virginia, which is overseen not by a state entity, but by a monopoly utility, a regulated monopoly utility. Where do you come out on this debate?

Jane Flegal:

[21:27] Like any thoughtful policy analyst, I refuse to choose a side. I think there are lessons from both that are worth taking. Right. So I do sometimes wonder if I could rewind the clock. Do I really believe that restructuring was a good thing to do? I don’t actually know that I have an answer to that. For me, it feels quite complicated. There are for sure, and I’m sure this is true in the literature, efficiency gains associated with market competition on the generation side. But all of this has happened again in a time of flat demand growth, right? So like, fine, maybe that’s what you care most about when you’re not tripling the grid, right? You’re like, okay, cool. Like what’s most important is having the generators compete. One thing you give up is that you don’t have the same level of kind of like centralized planning and oversight that you have in a vertically integrated market with a public utility commission and a state setting policy objectives in overseeing these things. Now, Texas, I think there’s lots to be said about kind of the market logic there. But I think one of the things that I think is most important about the Texas model is the way that they’ve approached transmission.

Jane Flegal:

[22:43] So there are a couple of things about Texas. One, they have incredible natural resources. So they don’t have to mandate anything about renewables deployment in that state, right? And like, it’s just a very good latitudinal environment to build.

Robinson Meyer:

[22:59] And they have incredible natural resources, no matter what resource you count. So they have abundant oil and gas if you don’t care about carbon, and they have abundant wind and solar if you do care about carbon.

Jane Flegal:

[23:09] Exactly. And they have... Faster interconnection and siting than almost anywhere else, in part because they have streamlined their transmission siting process. And they did these, what is CREZ, competitive renewable energy zones.

Robinson Meyer:

[23:23] They basically centrally planned transmission.

Jane Flegal:

[23:26] Yeah, they like basically did the thing that I’m saying we should do at a national scale, which is like build it and they will come in terms of demand and customers and plan proactively.

Robinson Meyer:

[23:36] Back in the 2000s, Texas built out this giant transmission line out to West Texas, where at the time there was very little generation because it anticipated that people would eventually build wind turbines there. And then the cities in eastern Texas would benefit from cheap electricity from West Texas. What’s interesting, if you go back and read the press accounts of this decision, is that it was all about this gap in timing where people said it takes two to three years to build a wind farm, but it takes six to 10 years. Now it’s longer than that to build a transmission line. And so people will never build wind farms unless we start building a transmission line. So we should front run a transmission line and then people will invest in wind farms once they know that there’s going to be a transmission line between West Texas and East Texas. It’s an interesting case because it’s a, it is a centrally planned transmission line. And I think the Texas example speaks well of centrally planned transmission, but it’s done so with a kind of market failure logic to it where nobody’s going to invest in wind unless we build a transmission line first.

Jane Flegal:

[24:34] Which is fine. Like that’s fine. That’s fine as far as I’m concerned. Like that’s why I’m unwilling to pick one of your two paradigms. I’m kind of like some blend of these two things feels both like potentially politically plausible to me. And like you might be able to kind of navigate this such that you sort of get the best of both worlds. The other like crazy idea I’ve been toying with on this issue is like, In Texas, the thing that is supposed to make sure that you have reliability is that you have like scarcity pricing, basically, right? Like prices are supposed to go very high when you have a need for more supply and that’s supposed to bring more supply online. In other markets like PJM or whatever, you have capacity markets, which are a different way of trying to address this issue of getting like more supply online such that we have reliable systems. I think both of those are like not great like they’re both they’re both kind of like struggling in their own ways you saw with like winter storm uri in texas some of the frailties of their model and then obviously I genuinely don’t want to talk about PJM anymore but there’s what’s happening there if we really were to get away out of this like scarcity mindset on the energy supply side you could imagine a world where like I don’t know the federal government had a basically like.

Jane Flegal:

[25:51] Like strategic reliability reserve or something where like they were the government was actually like backstopping or financing this issue of like peak demand for reliability purposes.

Robinson Meyer:

[26:04] What’s interesting is the scarcity model is driven by the fact that ultimately rate payers that is utility customers are where the buck stops and so state regulators don’t want utilities to overbuild for a given moment, because ultimately it is utility customers. It’s people who pay their power bills who will bear the burden of a utility overbuilding. In some ways, the entire restructured electricity market system, the entire shift to electricity markets in the 90s and aughts was because of this belief that utilities were overbuilding. And what’s been funny is that, what, we started restructuring markets around the year 2000 for about five or six or seven years. Wall Street was willing to finance new electricity I mean I hear two stories here basically it’s another place where I hear two stories and I think where there’s a lot of disagreement about the path forward on electricity policy and that I’ve heard a story that basically electricity restructuring starts in the late 90s you know year 2000 and for five years Wall Street is willing to finance new power investment based entirely on price risk based entirely on the idea that market prices for electricity will go up. Then three things happen. The Great Recession, number one, wipes out investment,

Robinson Meyer:

[27:19] Wipes out some future demand. Number two, fracking. Power prices tumble, and a bunch of plays that people had invested in, including then advanced nuclear, are totally out of the money suddenly. Number three, we get electricity demand growth plateaus, right? So for 15 years, electricity demand plateaus. We don’t need to finance investments into the power grid anymore. This whole question of can you do it on the back of price risk goes away because it’s electricity demand is basically flat and different kinds of generation are competing over shares and gas is so cheap that it’s just whittling away.

Jane Flegal:

[27:56] But this is why that paradigm needs to change yet again. Like we need to pivot to like a growth model where, and I’m not, again.

Robinson Meyer:

[28:06] I think what’s interesting though, is that Texas is the other counterexample here because Texas has had robust load growth for years and a lot of investment in power production in Texas is financed off price risk, is financed off the assumption that prices will go up. Now, it’s also financed off the back of the fact that in Texas, there are a lot of rules and it’s a very clear structure around finding firm offtake for your powers. You can find a customer who’s going to buy 50% of your power. And that means that you feel confident in your investment. And then the other 50% of your generation capacity feeds into ERCOT. But in some ways, what the transit, the transition that feels disruptive right now is not only a transition like market structure, but also like the assumptions of market participants about what electricity prices will be in the future.

Jane Flegal:

[28:51] Yeah, and we may need some like backstop. I hear the concerns about the risks of laying early capital risks basically on rate payers in the frame of like growth rather than scarcity. But I guess my argument is just there’s ways to deal with that. Like we could come up with creative ways to think about dealing with that. And I’m not seeing enough ideation in that space, which I would like,

Jane Flegal:

[29:15] again, a call for papers, I guess. That I would really like to get a better handle on. The other thing that we haven’t talked about, but that I do think, you know, the States Forum, where I’m now a senior fellow, I wrote a piece for them on electricity affordability several months ago now. But one of the things that doesn’t get that much attention is just like getting BS off of bills, basically. So there’s like the rate question, but then there’s the like, what’s in a bill? And like, what, what should or should not be in a bill? And in truth.

Jane Flegal:

[29:49] You know, we’ve got a lot of social programs basically that are being funded by the rate base and not the tax base. And I think there are just like open questions about this, whether it’s, you know, wildfire in California, which I think everyone recognizes is a big challenge, or it’s efficiency or electrification or renewable mandates in blue states. There are a bunch of these things and it’s sort of like there are so few things you can do in the very near term to constrain rate increases for the reasons we’ve discussed. And also, by the way, just because we have an aging grit, like we just happen to be at like a year 60 in the investment cycle in the grid. And like we don’t really have a choice. Like we do have to invest in the grid, even if there wasn’t demand growth, you know.

Robinson Meyer:

[30:34] Warren Buffett says you can’t see who’s swimming naked till the tide goes out. And I feel like there’s a bit of an inverse problem that has happened here where a number of blue states paid for a lot of social programs off fees placed on the electricity bill. Some of those social programs, I think we could say are essential, like the retrofits that are happening in California. But in the Northeast, there’s a lot of other charges that appear on the bill that finance social programs that I think made sense in an era of declining electricity prices. And the issue now is that because electricity demand is going up and electricity prices are going up for reasons that don’t only have to do with data centers, for reasons that have to do with the natural gas got more expensive in 2022 after Russia invaded Ukraine and that pushed up prices particularly in new england which relies on more seaborne natural gas suddenly those charges which were not really noticeable and not really salient in a world where underlying electricity prices are falling suddenly become quite politically salient um last question do you think the path forward on these policies is to talk about climate. Or should Democrats, I don’t know whether it’s Democrats, I don’t know whether it’s think tanks, I don’t know whether it’s advocacy groups, should talk less about climate and indeed kind of sublimate their concern over climate into concern over things like, well, we need cheap electricity because that will ultimately help the cause of electrification.

Jane Flegal:

[32:00] Look, I think it is pretty obvious at this stage that climate does not have the cultural or political significance it had in 2020. That seems very obvious to me. I do not foresee that changing anytime in the immediate future. That doesn’t mean that no one should talk about climate change and we shouldn’t acknowledge the physics of the world in which we live. Fine. it’s pretty obvious to me that leading with climate is not going to be a winning strategy, my bigger concern is okay so then what do you lead with and how does what you lead with affect our ability to actually decarbonize and again that’s where it’s sort of like affordability is great if it actually is incentivizing the right things we need to incentivize not only to decarbonize, but I would argue to like power the economic growth of our country and deal with some of our biggest geopolitical anxieties right now. And like, that’s why I get so anxious about like, oh my God, if affordability becomes the only frame, what are we losing?

Jane Flegal:

[33:10] How do we find the right way to both like inject a consideration of affordability that is not so short term that we are like losing sight of the structural drivers of affordability in our economy, especially in the electricity sector. And, you know, another thing about the affordability piece is it’s sort of affordable to whom? So there’s lots of conversations about, for instance, rooftop solar in certain situations, being a cost effective strategy for an individual homeowner, right? That is not the same thing.

Robinson Meyer:

[33:45] It’s insane. It’s insane that we can talk about rooftop solar as an affordability strategy.

Jane Flegal:

[33:49] Yes, yes. And then I just think as a political matter, like, There’s a question for me of whether we’re overlearning the lessons of the end of the Biden administration where we very obviously did not take inflation seriously enough. But now it’s sort of like, are we becoming so inflation pilled that we’re not actually like substantively or politically leading with the most compelling strategies? If you actually looked at like the list of things that could potentially constrain electricity prices in the next two years, it’s not a particularly sexy or compelling agenda. In my view, it feels it’s giving it’s a little bit giving like Jimmy Carter put a sweater on. It’s a little bit or it’s at least an easy target for Republicans in that way. Right. It’s a little like efficiency, demand response. Don’t let utilities make money. And like all of these things may be good in their own right. So I’m not I’m not dismissing them as as tactics. But I think like having that be the kind of structure of the argument for Democrats on climate is like, I think we would make us very vulnerable.

Robinson Meyer:

[34:53] Anyway, Jane, we’re going to have you back on. Thank you so much for joining us on Shift Key.

Jane Flegal:

[34:57] Thanks, Robinson.

Robinson Meyer:

[35:01] If you enjoyed this episode of Shift Key, please leave us a review on your favorite podcast app. You can reach me as always at shiftkey at heatmap.news. This will do it for us this week. We’ll be back next week with a new episode of Shift Key. Until then, enjoy your weekend. Shift key, as always, is a production of Heatmap News. Our editors are Jillian Goodman and Nico Loricella. Multimedia editing and audio engineering is by Jacob Lambert and by Nick Woodbury. Our music is by Adam Kramelow. Thanks so much for listening. I’ll see you next week.