You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

On the exaggerated danger of renewables in a blackout

Gas stoves and heating systems are two of the biggest ways that fossil fuels still find their way into our homes. Replacing them with electric stoves and heat pumps would go a long way to reducing our commercial and residential carbon footprint, which the EPA says amounts to 13 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions. There’s one little problem: blackouts.

Without battery backup or a generator, everything powered by electricity goes dead when the grid goes down. With major blackouts a rising threat because of worsening wildfires and winter storms, and with our national demand for electricity rising, the plan to “electrify everything” in our homes (and the cars in our garages) may sound worrisome. Wouldn’t it leave us all more vulnerable — unable to heat our homes, cook our food, or drive anywhere when the power goes out?

Don’t be so sure.

At first blush, fossil fuels sound resilient. A fuel like natural gas is just sitting there, waiting to burn and unleash the power within, whether or not the electricity is on. A modern gas stove probably has an electric control panel and ignition, but a person can bypass a modern stove’s electric ignition by using a match to light the burners as long as gas is flowing. However, saying that gas stoves work during an emergency and electric ones won’t isn’t quite true, research scientist Pablo Duenas-Martinez of the MIT Energy Initiative told me.

For one thing, natural gas isn’t disaster-proof. The same kinds of calamities that can disrupt the power grid could also potentially break gas lines or damage the distribution system that moves the fossil fuel to your home. Duenas-Martinez also noted that the substations that compress and distribute gas themselves rely on electricity. So, in the case of widespread power outages, they may not be able to deliver gas to your stove or furnace.

As for that electric stove? Well, we already know how to make backup electricity. Buildings where the power must stay on 24/7, like hospitals and military installations have diesel-burning backup generators. Lots of private homeowners have them, too, and can run the heat pump and stove alongside the lights and the TV.

From a climate perspective, it somewhat defeats the purpose of “electrify everything” if we’re still reliant on dirty generators. Fortunately, cleaner ways to solve this problem are coming. Homes with solar panels could generate their own juice, at least during daylight hours. But improving our ability to store energy will be the game-changer.

Eminent MIT economist Richard Schmalensee told me that the cost of energy storage should fall over the years, especially as the transition to electric vehicles requires building lots and lots of batteries. Big batteries and other avant garde storage solutions will help the electricity system avoid some blackouts in the first place by storing energy when there is ample supply to use later during leaner times.

Better electric storage solutions will come to the house or neighborhood level, Duenas-Martinez said, with some neighborhoods installing backup systems to provide electricity to all their homes during a blackout. Individuals can install backup systems like the Tesla Powerwall, which stores energy from a home’s solar panels to use as backup power later. And a fast-growing number of Americans already have a way to store lots of electricity — the battery in their EV.

Electric cars present a curious case. On the one hand, gasoline-burning vehicles are blackout-proof, so one’s mobility is mostly unaffected by outage, emergency, or calamity (they drive on “guzzoline” in Mad Max, after all, not electrons). When most people have an EV, losing electricity becomes more of a predicament. “Currently, EVs may be more vulnerable than current fossil fueled vehicles because gas stations are very accessible, and the logistics chain for gasoline is well-established,” Duenas-Martinez said.

If an EV's battery is low when a big blackout happens, it may become essentially undriveable, and its voracious energy consumption compared to a toaster or a stove makes refilling the battery from backup systems more difficult. In the case of a sustained power outage, people may have to prioritize what to do with the limited backup power they have — whether they use it for heating and cooling, lights, TV, working on their laptops, doing the laundry, or charging EVs.

Yet EVs will become more resilient as infrastructure gets better, he says. With more chargers available at workplaces, public places, and people’s homes, our EVs will stay mostly charged more often than not. When the power goes out, they’ll have enough energy on hand for a few days’ worth of normal driving.

Plus, what if the car is your backup system? Although the feature is not ubiquitous among today’s models, it is possible to give EVs two-way charging, or the ability to plug in and run other items on the energy in the car’s battery. Ford F-150 Lightning commercials play up the truck’s potential to power an entire home for days at a time. According to researchers like Steven Low at Caltech (full disclosure: it’s also where I work), EV batteries could even be used to balance the grid of the future. While the cars sit parked and unused, they could feed electricity into the system in times of crisis and refill when there’s more to go around.

“The EV battery could help restore service by injecting electricity to the grid,” Duenas-Martinez said. “So, for short blackouts, I would not expect more vulnerability once more chargers are installed.”

When the culture wars came into the kitchen this past January, thanks to the controversy of (maybe) banning gas stoves, the ruckus started over indoor air pollution. But with gas stoves and heaters also a villian in the climate change story, and with electric stoves primed to become much less expensive than their gas counterparts, there’s ample reason to think gas stoves, like gasoline-powered cars, could be on their way out.

When they are, don’t worry — it doesn’t mean you won’t be able to make a hot pot of tea or drive to the grocery store in the middle of a blackout. But it will require a new way to think about home energy.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The maker of the Prius is finally embracing batteries — just as the rest of the industry retreats.

Selling an electric version of a widely known car model is no guarantee of success. Just look at the Ford F-150 Lightning, a great electric truck that, thanks to its high sticker price, soon will be no more. But the Toyota Highlander EV, announced Tuesday as a new vehicle for the 2027 model year, certainly has a chance to succeed given America’s love for cavernous SUVs.

Highlander is Toyota’s flagship titan, a three-row SUV with loads of room for seven people. It doesn’t sell in quite the staggering numbers of the two-row RAV4, which became the third-best-selling vehicle of any kind in America last year. Still, the Highlander is so popular as a big family ride that Toyota recently introduced an even bigger version, the Grand Highlander. Now, at last, comes the battery-powered version. (It’s just called Highlander and not “Highlander EV,” by the way. The Highlander nameplate will be electric-only, while gas and hybrid SUVs will fly the Grand Highlander flag.)

The American-made electric Highlander comes with a max range of 287 miles in its less expensive form and 320 in its more expensive form. The SUV comes with the NACS port to charge at Tesla Superchargers and vehicle-to-load capability that lets the driver use their battery power for applications like backing up the home’s power supply. Six seats come standard, but the upgraded Highlander comes with the option to go to seven. The interior is appropriately high-tech.

Toyota will begin to build this EV later this year at a factory in Kentucky and start sales late in the year. We don’t know the price yet, but industry experts expect Highlander to start around $55,000 — in the same ballpark as big three-row SUVs like the Kia EV9 and Hyundai Ioniq 9 — and go up from there.

The most important point of the electric Highlander’s arrival, however, is that it signals a sea change for the world’s largest automaker. Toyota was decidedly not all in on the first wave (or two) of modern electric cars. The Japanese giant was content to make money hand over first while the rest of the industry struggled, losing billions trying to catch up to Tesla and deal with an unpredictable market for electrics.

A change was long overdue. This year, Toyota was slated to introduce better EVs to replace the lackluster bZ4x, which had been its sole battery-only model. That included an electrified version of the C-HR small crossover. Now comes the electrified Highlander, marking a much bigger step into the EV market at a time when other automakers are reining in their battery-powered ambitions. (Fellow Japanese brand Subaru, which sold a version of bZ4x rebadged as the Solterra, seems likely to do the same with the electric Highlander and sell a Subaru-labeled version of essentially the same vehicle.)

The Highlander EV matters to a lot of people simply because it’s a Toyota, and they buy Toyotas. This pattern was clear with the success of the Honda Prelude. Under the skin that car was built on General Motors’ electric vehicle platform, but plenty of people bought it because they were simply waiting for their brand, Honda, to put out an EV. Toyota sells more cars than anyone in the world. Its act of putting out a big family EV might signal to some of its customers that, yeah, it’s time to go electric.

Highlander’s hefty size matters, too. The five-seater, two-row crossover took over as America’s default family car in the past few decades. There are good EVs in this space, most notably the Tesla Model Y that has led the world in sales for a long time. By contrast, the lineup of true three-row SUVs that can seat six, seven, or even eight adults has been comparatively lacking. Tesla will cram two seats in the back of the Model Y to make room for seven people, but this is not a true third row. The excellent Rivian R1S is big, but expensive. Otherwise, the Ioniq 9 and EV9 are left to populate the category.

And if nothing else, the electrified Highlander is a symbolic victory. After releasing an era-defining auto with the Prius hybrid, Toyota arguably had been the biggest heel-dragger about EVs among the major automakers. It waited while others acted; its leadership issued skeptical statements about battery power. Highlander’s arrival is a statement that those days are done. Weirdly, the game plan feels like an announcement from the go-go electrification days of the Biden administration — a huge automaker going out of its way to build an important EV in America.

If it succeeds, this could be the start of something big. Why not fully electrify the RAV4, whose gas-powered version sells in the hundreds of thousands in America every year?

Third Way’s latest memo argues that climate politics must accept a harsh reality: natural gas isn’t going away anytime soon.

It wasn’t that long ago that Democratic politicians would brag about growing oil and natural gas production. In 2014, President Obama boasted to Northwestern University students that “our 100-year supply of natural gas is a big factor in drawing jobs back to our shores;” two years earlier, Montana Governor Brian Schweitzer devoted a portion of his speech at the Democratic National Convention to explaining that “manufacturing jobs are coming back — not just because we’re producing a record amount of natural gas that’s lowering electricity prices, but because we have the best-trained, hardest-working labor force in the history of the world.”

Third Way, the long tenured center-left group, would like to go back to those days.

Affordability, energy prices, and fossil fuel production are all linked and can be balanced with greenhouse gas-abatement, its policy analysts and public opinion experts have argued in a series of memos since the 2024 presidential election. Its latest report, shared exclusively with Heatmap, goes further, encouraging Democrats to get behind exports of liquified natural gas.

For many progressive Democrats and climate activists, LNG is the ultimate bogeyman. It sits at the Venn diagram overlap of high greenhouse gas emissions, the risk of wasteful investment and “stranded” assets, and inflationary effects from siphoning off American gas that could be used by domestic households and businesses.

These activists won a decisive victory in the Biden years when the president put a pause on approvals for new LNG export terminal approvals — a move that was quickly reversed by the Trump White House, which now regularly talks about increases in U.S. LNG export capacity.

“I think people are starting to finally come to terms with the reality that oil and gas — and especially natural gas— really aren’t going anywhere,” John Hebert, a senior policy advisor at Third Way, told me. To pick just one data point: The International Energy Agency’s latest World Energy Outlook included a “current policies scenario,” which is more conservative about policy and technological change, for the first time since 2019. That saw the LNG market almost doubling by 2050.

“The world is going to keep needing natural gas at least until 2050, and likely well beyond that,” Hebert said. “The focus, in our view, should be much more on how we reduce emissions from the oil and gas value chain and less on actually trying to phase out these fuels entirely.”

The memo calls for a variety of technocratic fixes to America’s LNG policy, largely to meet demand for “cleaner” LNG — i.e. LNG produced with less methane leakage — from American allies in Europe and East Asia. That “will require significant efforts beyond just voluntary industry engagement,” according to the Third Way memo.

These efforts include federal programs to track methane emissions, which the Trump administration has sought to defund (or simply not fund); setting emissions standards with Europe, Japan, and South Korea; and more funding for methane tracking and mitigation programs.

But the memo goes beyond just a few policy suggestions. Third Way sees it as part of an effort to reorient how the Democratic Party approaches fossil fuel policy while still supporting new clean energy projects and technology. (Third Way is also an active supporter of nuclear power and renewables.)

“We don’t want to see Democrats continuing to slow down oil and gas infrastructure and reinforce this narrative that Democrats are just a party of red tape when these projects inevitably go forward anyway, just several years delayed,” Hebert told me. “That’s what we saw during the Biden administration. We saw that pause of approvals of new LNG export terminals and we didn’t really get anything for it.”

Whether the Democratic Party has any interest in going along remains to be seen.

When center-left commentator Matthew Yglesias wrote a New York Times op-ed calling for Democrats to work productively with the domestic oil and gas industry, influential Democratic officeholders such as Illinois Representative Sean Casten harshly rebuked him.

Concern over high electricity prices has made some Democrats a little less focused on pursuing the largest possible reductions in emissions and more focused on price stability, however. New York Governor Kathy Hochul, for instance, embraced an oft-rejected natural gas pipeline in her state (possibly as part of a deal with the Trump administration to keep the Empire Wind 1 project up and running), for which she was rewarded with the Times headline, “New York Was a Leader on Climate Issues. Under Hochul, Things Changed.”

Pennsylvania Governor Josh Shapiro (also a Democrat) was willing to cut a deal with Republicans in the Pennsylvania state legislature to get out of the Northeast’s carbon emissions cap and trade program, which opponents on the right argued could threaten energy production and raise prices in a state rich with fossil fuels. He also made a point of working with the White House to pressure the region’s electricity market, PJM Interconnection, to come up with a new auction mechanism to bring new data centers and generation online without raising prices for consumers.

Ruben Gallego, a Democratic Senator from Arizona (who’s also doing totally normal Senate things like having town halls in the Philadelphia suburbs), put out an energy policy proposal that called for “ensur[ing] affordable gasoline by encouraging consistent supply chains and providing funding for pipeline fortification.”

Several influential Congressional Democrats have also expressed openness to permitting reform bills that would protect oil and gas — as well as wind and solar — projects from presidential cancellation or extended litigation.

As Democrats gear up for the midterms and then the presidential election, Third Way is encouraging them to be realistic about what voters care about when it comes to energy, jobs, and climate change.

“If you look at how the Biden administration approached it, they leaned so heavily into the climate message,” Hebert said. “And a lot of voters, even if they care about climate, it’s just not top of mind for them.”

Current conditions: A foot of snow piled up on Hawaii's mountaintops • Fresh snow in parts of the Northeast’s highlands, from the New York Adirondacks to Vermont’s Green Mountains, could top 10 inches • The seismic swarm that rattled Iceland with more than 600 relatively low-level earthquakes over the course of two days has finally subsided.

Say what you will about President Donald Trump’s cuts to electric vehicles, renewables, and carbon capture, the administration has given the nuclear industry red-carpet treatment. The Department of Energy refashioned its in-house lender into a financing hub for novel nuclear projects. After saving the Biden-era nuclear funding from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act’s cleaver, the agency distributed hundreds of millions of dollars to specific small modular reactors and rolled out testing programs to speed up deployment of cutting-edge microreactors. The Department of Commerce brokered a deal with the Japanese government to provide the Westinghouse Electric Company with $80 billion to fund construction of up to 10 large-scale AP1000 reactors. But still, in private, I’m hearing from industry sources that utilities and developers want more financial protection against bankruptcy if something goes wrong. My sources tell me the Trump administration is resistant to providing companies with a blanket bailout if nuclear construction goes awry. But legislation in the Senate could step in to provide billions of dollars in federal backing for over-budget nuclear reactors. Senator Jim Risch, an Idaho Republican, previously introduced the Accelerating Reliable Capacity Act in 2024 to backstop nuclear developers still reeling from the bankruptcies associated with the last AP1000 buildout. This time, as E&E News noted, “he has a prominent Democrat as a partner.” Senator Ruben Gallego, an Arizona Democrat who stood out in 2024 by focusing his campaign’s energy platform on atomic energy and just recently put out an energy strategy document, co-sponsored the bill, which authorizes up to $3.6 billion to help offset cost overruns at three or more next-generation nuclear projects.

Nuclear generation set a new global record in 2025, the International Energy Agency said in its latest electricity outlook published last Friday. That’s largely thanks to Japan restarting reactors idled after Fukushima, France ramping up generation at its fleet, and China and India opening new plants. By 2030, however, China will account for 40% of the global increase in nuclear generation. You can see the difference in the growth rate already. Nuclear power worldwide is on track to grow by an average of 2.8% per year, more than double the 1.3% pace of the previous four years. China’s nuclear capacity, by contrast, will grow by an average of 6% per year through the end of the decade.

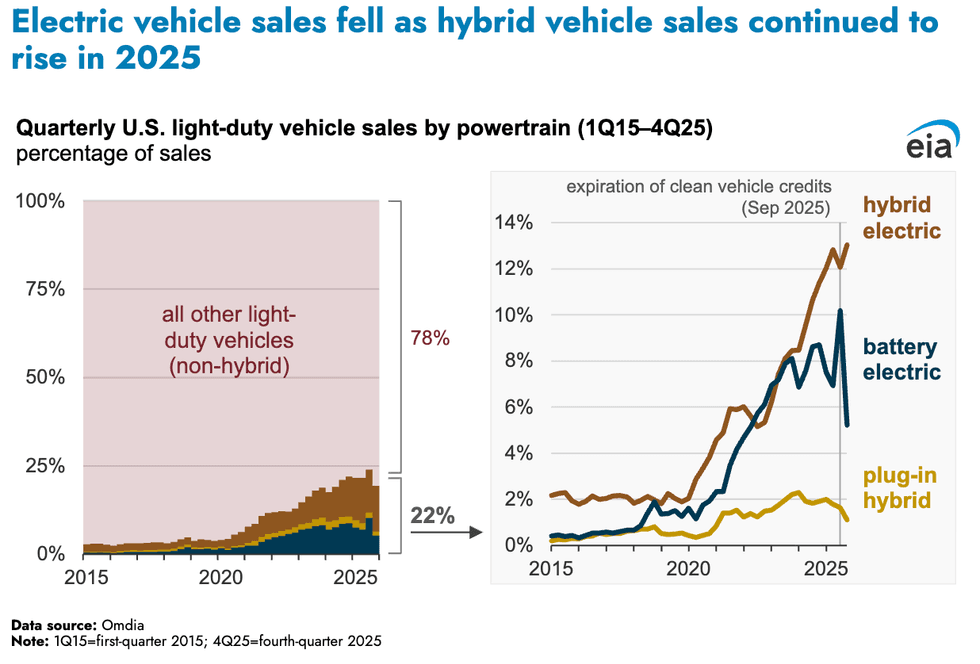

Roughly 22% of light-duty vehicles sold last year in the U.S. were hybrid and battery electric, up from 20% in 2024. While sales of battery-powered vehicles have fallen, demand for hybrids has only increased, according to estimates from the research firm Omdia that the U.S. Energy Information Administration highlighted in a new analysis. Electric vehicles accounted for just 2% of all registered light-duty vehicles on U.S. roads in 2024, the most recent year for which annual data is available. Sales for 2025 will show a spike, especially around September when Americans rushed to cash in on electric vehicle tax credits before Trump’s phaseout took effect.

The Department of Transportation, meanwhile, proposed boosting the domestic content requirements for federally funded electric vehicle charging stations from 55% to 100%. The Biden administration had waived some “Buy American” requirements for the $5 billion federal program to fund the infrastructure buildout. The proposal would set steep hurdles for projects, likely slowing the rollout of chargers. The agency, Reuters reported, said it believes it must “protect Americans from foreign-made EV charger components that use technology with cybersecurity vulnerabilities.”

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Equinor is scaling back its near-term investments in carbon capture and sequestration projects as prices go up and customer demand stagnates. Despite its reputation as what the Carbon Herald called “one of the global standard-bearers for carbon capture and storage,” the Norwegian energy giant said the commercial conditions needed to justify more large-scale investments in carbon pipelines and wells were not yet there. CEO Anders Opedal said during the company’s latest earnings call that, because CCS markets were growing more slowly than previously thought, Equinor would hold off on committing more capital to new projects.

CCS had something of a moment last fall when Google agreed to finance construction of a gas plant equipped with carbon capture technology, as Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote. But Trump’s plan to go for the climate killshot, repealing the legal underpinning of all federal regulations on planet-heating emissions, would really dampen demand for CCS in the U.S.

The new U.S.-India trade deal that will lower tariffs on Indian goods to 18% from 25% is set to bolster the country’s booming solar manufacturing industry. The pact represents what Prashant Mathur, chief executive of the solar manufacturer Saatvik Green Energy, described to PV-Tech as a “strategic turning point.” Cutting tariffs by seven percentage points “materially improves cost competitiveness, making U.S. projects more profitable and creating new demand for high-efficiency, Made-in-India products.” Gyanesh Chaudhary, the managing director of Vikram Solar, called the deal a “structural inflection point.” But the trade agreement won’t fix all the problems for Indian solar exporters. New restrictions known as Section 232 tariffs, which raise prices on imports that threaten national security by undercutting domestic manufacturers, are expected to come into effect on India’s exports of polysilicon. A separate antidumping and countervailing duty investigation into whether India is unfairly flooding the U.S. market with cheap crystalline silicon solar cells called for a duty of 123.04%, though nothing has yet been imposed.

The Trump administration, meanwhile, is setting the stage for more coal in the U.S. On Wednesday, according to Bloomberg, Trump plans to sign an executive order directing the military to buy more power from coal-fired plants in a bid to prop up the sector.

Despite Trump’s best attempts to stop it, Orsted is finishing its offshore wind farms in New England and, after that, is expected to save its money for new projects overseas. In its native Europe, the energy giant is preparing for a big multinational buildout in the North Sea. Now the Danish developer is charging ahead in a new market. Australia does not have any operating offshore wind farms. But Orsted just submitted an application for an environmental review of a 2.8 gigawatt project proposed off the coast of Gippsland, Victoria. Together with a second site Orsted started lining up in 2024, the area could host a combined 4.8 gigawatts of turbine capacity, according to Renewables Now.

Yet another fusion energy startup has officially entered the race. Inertia Enterprises, a fusion startup aimed at mimicking the technology that managed for the first time in history to generate more energy than it took to start the reaction, has raised $450 million in a Series A round. The venture firm Bessemer Venture Partners led the round, with backing from Google Ventures, Modern Capital, and Threshold Ventures. “Inertia is building on decades of science and billions of dollars invested to reach the ignition milestone that proved the science,” Jeff Lawson, the co-founder and chief executive of Inertia, said in a statement.