You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

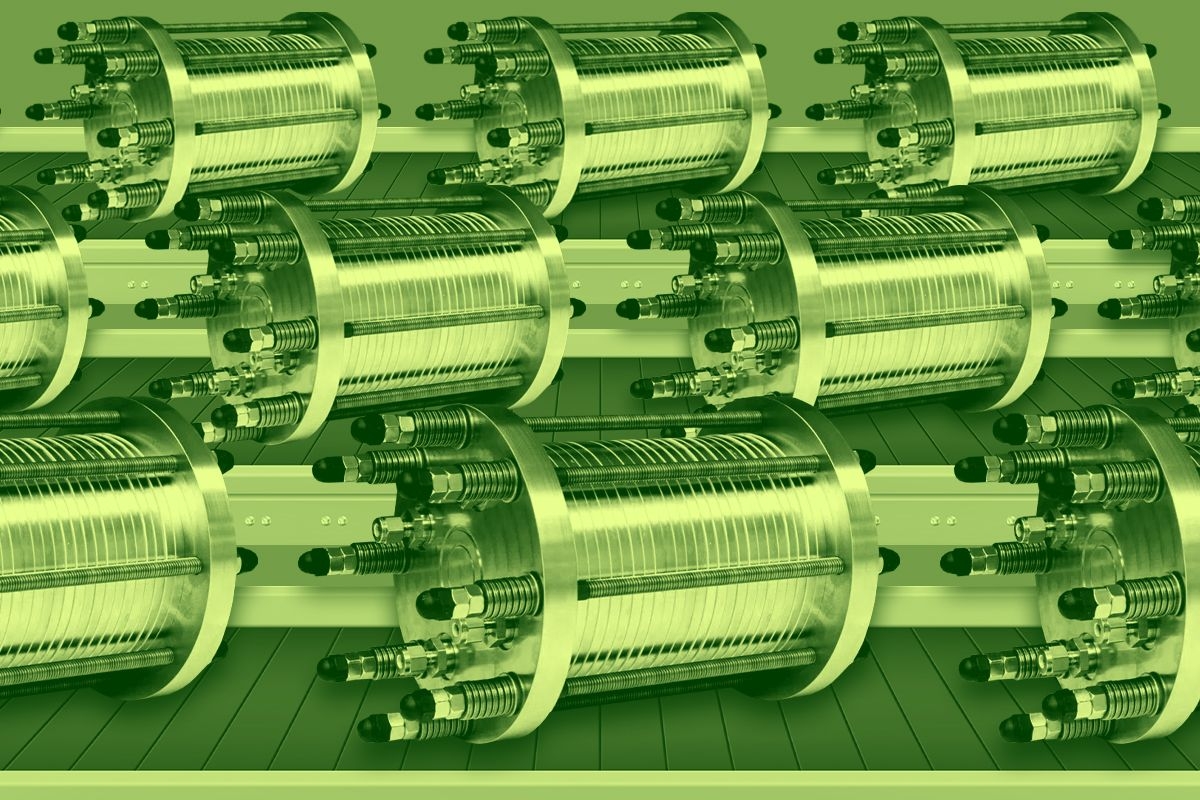

Ecolectro, a maker of electrolyzers, has a new manufacturing deal with Re:Build.

By all outward appearances, the green hydrogen industry is in a state of arrested development. The hype cycle of project announcements stemming from Biden-era policies crashed after those policies took too long to implement. A number of high profile clean hydrogen projects have fallen apart since the start of the year, and deep uncertainty remains about whether the Trump administration will go to bat for the industry or further cripple it.

The picture may not be as bleak as it seems, however. On Wednesday, the green hydrogen startup Ecolectro, which has been quietly developing its technology for more than a decade, came out with a new plan to bring the tech to market. The company announced a partnership with Re:Build Manufacturing, a sort of manufacturing incubator that helps startups optimize their products for U.S. fabrication, to build their first units, design their assembly lines, and eventually begin producing at a commercial scale in a Re:Build-owned factory.

“It is a lot for a startup to create a massive manufacturing facility that’s going to cost hundreds of millions of dollars when they’re pre-revenue,” Jon Gordon, Ecolectro’s chief commercial officer, told me. This contract manufacturing partnership with Re:Build is “massive,” he said, because it means Ecolectro doesn’t have to take on lots of debt to scale. (The companies did not disclose the size of the contract.)

The company expects to begin producing its first electrolyzer units — devices that split water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity — at Re:Build’s industrial design and fabrication site in Rochester, New York, later this year. If all goes well, it will move production to Re:Build’s high-volume manufacturing facility in New Kensington, Pennsylvania next year.

The number one obstacle to scaling up the production and use of cleaner hydrogen, which could help cut emissions from fertilizer, aviation, steelmaking, and other heavy industries, is the high cost of producing it. Under the Biden administration, Congress passed a suite of policies designed to kick-start the industry, including an $8 billion grant program and a lucrative new tax credit. But Biden only got a small fraction of the grant money out the door, and did not finalize the rules for claiming the tax credit until January. Now, the Trump administration is considering terminating its agreements with some of the grant recipients, and Republicans in Congress might change or kill the tax credit.

Since the start of the year, a $500 million fuel plant in upstate New York, a $400 million manufacturing facility in Michigan, and a $500 million green steel factory in Mississippi, have been cancelled or indefinitely delayed.

The outlook is particularly bad for hydrogen made from water and electricity, often called “green” hydrogen, according to a recent BloombergNEF analysis. Trump’s tariffs could increase the cost of green hydrogen by 14%, or $1 per kilogram, based on tariff announcements as of April 8. More than 70% of the clean hydrogen volumes coming online between now and 2030 are what’s known as “blue” hydrogen, made using natural gas, with carbon capture to eliminate climate pollution. “Blue hydrogen has more demand than green hydrogen, not just because it’s cheaper to produce, but also because there’s a lot less uncertainty around it,” BloombergNEF analyst Payal Kaur said during a presentation at the research firm’s recent summit in New York City. Blue hydrogen companies can take advantage of a tax credit for carbon capture, which Congress is much less likely to scrap than the hydrogen tax credit.

Gordon is intimately familiar with hydrogen’s cost impediments. He came to Ecolectro after four years as co-founder of Universal Hydrogen, a startup building hydrogen-powered planes that shut down last summer after burning through its cash and failing to raise more. By the end, Gordon had become a hydrogen skeptic, he told me. The company had customers interested in its planes, but clean hydrogen fuel was too expensive at $15 to $20 per kilogram. It needed to come in under $2.50 to compete with jet fuel. “Regional aviation customers weren’t going to spend 10 times the ticket price just to fly zero emissions,” he said. “It wasn’t clear to me, and I don’t think it was clear to our prospective investors, how the cost of hydrogen was going to be reduced.” Now, he’s convinced that Ecolectro’s new chemistry is the answer.

Ecolectro started in a lab at Cornell University, where its cofounder and chief science officer Kristina Hugar was doing her PhD research. Hugar developed a new material, a polymer “anion exchange membrane,” that had potential to significantly lower the cost of electrolyzers. Many of the companies making electrolyzers use designs that require expensive and supply-constrained metals like iridium and titanium. Hugar’s membrane makes it possible to use low-cost nickel and steel instead.

The company’s “stack,” the sandwich of an anode, membrane, and cathode that makes up the core of the electrolyzer, costs at least 50% less than the “proton exchange membrane” versions on the market today, according to Gordon. In lab tests, it has achieved more than 70% efficiency, meaning that more than 70% of the electrical energy going into the system is converted into usable chemical energy stored in hydrogen. The industry average is around 61%, according to the Department of Energy.

In addition to using cheaper materials, the company is focused on building electrolyzers that customers can install on-site to eliminate the cost of transporting the fuel. Its first customer was Liberty New York Gas, a natural gas company in Massena, New York, which installed a small, 10-kilowatt electrolyzer in a shipping container directly outside its office as part of a pilot project. Like many natural gas companies, Liberty is testing blending small amounts of hydrogen into its system — in this case, directly into the heating systems it uses in the office building — to evaluate it as an option for lowering emissions across its customer base. The equipment draws electricity from the local electric grid, which, in that region, mostly comes from low-cost hydroelectric power plants.

Taking into account the expected manufacturing cost for a commercial-scale electrolyzer, Ecolectro says that a project paying the same low price for water and power as Liberty would be able to produce hydrogen for less than $2.50 per kilogram — even without subsidies. Through its partnership with Re:Build, the company will produce electrolyzers in the 250- to 500-kilowatt range, as well as in the 1- to 5-megawatt range. It will be announcing a larger 250-kilowatt pilot project later this year, Gordon said.

All of this sounded promising, but what I really wanted to know is who Ecolectro thought its customers were going to be. Demand for clean hydrogen, or the lack thereof, is perhaps the biggest challenge the industry faces to scaling, after cost. Of the roughly 13 million to 15 million tons of clean hydrogen production announced to come online between now and 2030, companies only have offtake agreements for about 2.5 million tons, according to Kaur of BNEF. Most of those agreements are also non-binding, meaning they may not even happen.

Gordon tied companies’ struggle with offtake to their business models of building big, expensive, facilities in remote areas, meaning the hydrogen has to be transported long distances to customers. He said that when he was with Universal Hydrogen, he tried negotiating offtake agreements with some of these big projects, but they were asking customers to commit to 20-year contracts — and to figure out the delivery on their own.

“Right now, where we see the industry is that people want less hydrogen than that,” he said. “So we make it much easier for the customer to adopt by leasing them this unit. They don’t have to pay some enormous capex, and then it’s on site and it’s producing a fair amount of hydrogen for them to engage in pilot studies of blending, or refining, or whatever they’re going to use it for.”

He expects most of the demand to come from industrial customers that already use hydrogen, like fertilizer companies and refineries, that want to switch to a cleaner version of the fuel, or hydrogen-curious companies that want to experiment with blending it into their natural gas burners to reduce their emissions. Demand will also be geographically-limited to places like New York, Washington State, and Texas, that have low-cost electricity available, he said. “I think the opportunity is big, and it’s here, but only if you’re using a product like ours.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The Army Corps of Engineers is out to protect “the beauty of the Nation’s natural landscape.”

A new Trump administration policy is indefinitely delaying necessary water permits for solar and wind projects across the country, including those located entirely on private land.

The Army Corps of Engineers published a brief notice to its website in September stating that Adam Telle, the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works, had directed the agency to consider whether it should weigh a project’s “energy density” – as in the ratio of acres used for a project compared to its power generation capacity – when issuing permits and approvals. The notice ended on a vague note, stating that the Corps would also consider whether the projects “denigrate the aesthetics of America’s natural landscape.”

Prioritizing the amount of energy generation per acre will naturally benefit fossil fuel projects and diminish renewable energy, which requires larger amounts of land to provide the same level of power. The Department of the Interior used this same tactic earlier in the year to delay permits.

Now we know the full extent of the delays wrought by that notice thanks to a copy of the Army Corps’ formal guidance on issuing permits under the Clean Water Act or approvals related to the Rivers and Harbors Act, a 1899 law governing discharges into navigable waters. That guidance was made public for the first time in a lawsuit filed in December by renewable trade associations against Trump’s actions to delay, pause, or deny renewables permits.

The guidance submitted in court by the trade groups states that the Corps will scrutinize the potential energy generation per acre of any permit request from an energy project developer, as well as whether an “alternative energy generation source can deliver the same amount of generation” while making less of an impact on the “aquatic environment.” The Corps is now also prioritizing permit applications for projects “that would generate the most annual potential energy generation per acre over projects with low potential generation per acre.”

Lastly, the Corps will also scrutinize “whether activities related to the projects denigrate the beauty of the Nation’s natural landscape” when deciding whether to issue these permits. That last factor – aesthetics – is in fact a part of the Army Corps’ permitting regulations, but I have not seen any previous administration halt renewable energy permits because officials think solar farms and wind turbines are an eyesore.

Jennifer Neumann, a former career Justice Department attorney who oversaw the agency’s water-related casework with the Army Corps for a decade, told me she had never seen the Corps cite aesthetics in this way. The issue has “never really been litigated,” she said. “I have never seen a situation where the Corps has applied [this].”

The renewable energy industry’s amended complaint in the lawsuit, which is slowly proceeding in federal court, claims the Corps’ guidance will lead to “many costly project redesigns” and delays, “resulting in contract penalties, cost hikes, and deferred revenue.” Other projects “may never get their Corps individual permits and thus will need to be canceled altogether.”

In addition, executives for the trade associations submitted a sworn declaration laying out how they’re being harmed by the Corps guidance, as well as a host of other federal actions against the renewable energy sector. To illustrate those harms they laid out an example: French energy developer ENGIE, they said, was required to “re-engineer” its Empire Prairie wind and solar farm in Missouri because the guidance “effectively precludes” it from getting a permit from the Army Corps. This cost ENGIE millions of dollars, per the declaration, and extended the construction timeline while ultimately also making the project less efficient.

Notably, Empire Prairie is located entirely on private land. It isn’t entirely clear from the declaration why the project had to be redesigned, and there is scant publicly available information about it aside from a basic website. The area where Empire Prairie is being built, however, is tricky for development; segments of the project are located in counties – DeKalb and Andrew – that have 88 and 99 opposition risk scores, respectively, per Heatmap Pro.

Renewable energy developers require these water permits from the Army Corps when their construction zone includes more than half an acre of federally designated wetlands or bodies of water protected under the Rivers and Harbors Act. Neumann told me that developers with impacts of half an acre or less may skirt the need for a permit application if their project qualifies for what’s known as a “nationwide permit,” which only requires verification from the Corps that a company complies with the requirements.

Even the simple verification process for Corps permits has been short-circuited by other actions from the administration. Developers are currently unable to access a crucial database overseen by the Fish and Wildlife Service to determine whether their projects impacts species protected under the Endangered Species Act, which in turn effectively “prevents wind and solar developers from (among other things) obtaining Corps nationwide permits for their projects,” according to the declaration from trade group executives.

But hey, look on the bright side. At least the Trump administration is in the initial phases of trying to pare back federal wetlands protections. So there’s a chance that eliminating federal environmental protections might benefit some solar and wind companies out there. How many? It’s quite unclear given the ever-changing nature of wetlands designations and opaque data available on how many projects are being built within those areas.

Dane County, Wisconsin – The QTS data center project we’ve been tracking closely is now dead, after town staff in the host community of DeForest declared its plans “unfeasible.”

Marathon County, Wisconsin – Elsewhere in Wisconsin, this county just voted to lobby the state’s association of counties to fight for more local control over renewable energy development.

Huntington County, Indiana – Meanwhile in Indiana, we have yet another loud-and-proud county banning data centers.

DeKalb County, Georgia – This populous Atlanta-adjacent county is also on the precipice of a data center moratorium, but is waiting for pending state legislation before making a move.

New York – Multiple localities in the Empire State are yet again clamping down on battery storage. Let’s go over the damage for the battery bros.

A conversation with Georgia Conservation Voters’ Connie Di Cicco.

This week’s conversation is with Connie Di Cicco, legislative director for Georgia Conservation Voters. I reached out to Connie because I wanted to best understand last November’s Public Service Commission elections which, as I explained at the time, focused almost exclusively on data center development. I’ve been hearing from some of you that you want to hear more about how and why opposition to these projects has become so entrenched so quickly. Connie argues it’s because data centers are a multi-hit combo of issues at the top of voters’ minds right now.

The following conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

So to start off Connie, how did we get here? What’s the tale of the tape on how data centers became a statewide election issue?

This has been about a year and a half-long evolution to where we are now. I started with GCV in about June of 2024 and I worked both the electoral and political sides. That meant I was working with PSC candidates.

People in other states have been dealing with data centers longer than we have and we’ve been taking our learnings from what they’ve been dealing with. We’ve been fortunate to be able to have them as resources.

There has been a coalition that has developed nationally and we have several groups that have developed within that coalition space who have helped us develop our site fight organizing, policy guidebooks, and legislative resources. It has been a tremendous assist to what we’re doing on the ground, because this is an ever-evolving situation. Almost like dealing with a virus or bacteria because it keeps mutating; as soon as you develop a tactic, the data centers react to that and you have to pivot, think of something else, and come up with a new strategy or tactic.

That’s been the last year and a half from the past summer to now. We worked on the Public Service Commission, flipping two seats this past legislative session. Now we have two more seats on the PSC looming in this next electoral year.

The next question I would ask is related to the role you view data centers will play in the coming election. Why do you think data centers are coming up? Help me understand what it is about data centers that has turned it into a potent political subject?

Georgia was in a really unique position in 2025 to have data centers at the forefront of the election. They were the only thing state-wide on the ballot because the PSC election was the only thing on the ballot. For the most part, Georgia has set up what is unique to Georgia: districted seats that the entire state can vote on. You have to live in the district to run for it but the entire state votes on it. And that meant we could message to the entire state what the PSC was, why it was important, and how it was going to affect people. Once you did that you were inevitably talking about data centers because that messaging became focused on affordability.

Once people understand what a PSC commissioner is, they know they regulate what you pay on your utility bill. If your bills are too high now, because the current PSC commissioners raised your rates six times in the past two years, there are more rate hikes looming in the future because of data centers. This is what’s coming.

Those were dots that were very easy for voters to connect.

We also had in the background and then the foreground data centers coming to people’s communities. Suddenly, random people were educated. They knew about closed-loop versus open-loop systems. They were asking questions suddenly about where water was coming from and why they didn’t know about these projects before they’re at the next local commission meeting. They’re telling me its only 50 decibels of noise. Are they going to cause cancer? The number of questions were tremendous and extremely sophisticated. People had been hearing about them, reading about them, and were knowledgeable until they connected all the dots.

You’re bringing up a really important phenomenon that, I’ll say, I’ve noticed when it comes to renewable energy projects and the opposition to projects: the populism I’ve seen in communities I’ve covered for the last year and a half here at Heatmap. So as someone who is trying to communicate against data center development but still trying to promote renewable energy, how do you walk that tightrope from a canvassing standpoint?

It’s a good question. Data centers are already coming. How we talk about data centers is, if they’re going to be here they need to be good neighbors.

We have made it open season here in Georgia. We left our credit card on the counter and said don’t do anything stupid only for us to come home and see there’s nothing left. What did you expect? There’s tax incentives for the data centers, there are no ordinances, they’ve allowed them to use our resources. They’ve come here because of our resources and our land and our access to fiber optics. Until we wrap our arms around it and put up some safeguards, and create rules for our teenagers when we go on Spring Break, then we can’t get a handle on how many of these are even going to be here and how much energy will be needed to power them.

We need to make limits. If you want incentives, okay – 30% of it needs to be green. If you want to build in a community, then okay – part of a CBA means you have to put up solar. They can be clean but we have to get a handle on protecting our resources, protecting the land and protecting our communities.

Do you see a change in the near-term when it comes to bringing data center development towards what you’d like to see, as opposed to just outright moratoria? Where is this opposition movement heading in Georgia?

We are just in the beginning phases of this. We see a lot of local opposition to data centers – 900 people coming out to county commissions. Like, we’re seeing unprecedented numbers.

What’s important is that power still rests with the elected officials. Unless they’re scared of losing power, it’s hard to actually change the rules. I think this state legislative session is going to be really important–

So how involved do you get at the local level on these data center fights?

So, those elected officials are on different schedules but people are showing up to meetings. We’re currently helping them organize and showing them best practices.

Now, I can’t dictate their messaging for them, because that’s county by county and the best people to do that are the people who live there, but we help coach them, tell them to pick a personal story, say how to show up, and wear bright-colored shirts. We have an entire tool kit that shows them the ABCs and 123s of organizing. What has worked in the past from other groups around the country for other groups to fight back.

But each county is different. Some counties may need the tax revenue. There’s a chance you may need one. So we say Georgians need to value Georgia and their resources need to be protected. We say, you need a solid community benefits agreement, this is what you should ask for and you need a lawyer.

Our position here is to help them get the resources and get connected. We pull from a lot of different sources and places who have been in this fight a lot longer.