You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Julie Liu is converting gas customers to heat pumps, one home at a time.

For Julie Liu, electrifying a home is like putting on an Off- Off- Broadway show.

Working almost entirely alone, Liu serves as producer, stage manager, and director, bankrolling the production, hiring the crew, arranging the logistics, choreographing the action, and dazzling the audience — the homeowner or tenants — along the way. Heat pumps and induction stoves are the stars. Plumbers, HVAC technicians, and insulation specialists sub in for set decorators, sound engineers, and costume designers. Electricians play themselves.

If all goes well, after just a week or so of focused, frenzied work, the show arrives at the grand finale: the capping of the gas line.

Liu has staged this performance more than 25 times since 2023 as the implementation contractor for Electric Advantage, an incentive program in New York offered by the gas and electric utility Con Edison. The program covers 100% of the cost of replacing a building owner’s gas-powered appliances with electric versions, plus installing insulation and air sealing. Although it sounds too good to be true, there’s no catch — except that you have to be lucky enough to own a building that’s eligible for the program and agree to cut your gas connection.

ConEd, as it’s known, delivers natural gas to just over a million customers in the Bronx, Manhattan, Northern Queens, and Westchester County, and qualifies buildings for the program by first identifying sections of pipeline on the peripheries of its network that are due for replacement. Then it runs a cost-benefit analysis. If it would be cheaper to electrify all of the buildings served by a given stretch of gas main than to dig up the street and replace the pipe, the company starts going out to the homeowners and businesses along the line to gauge their interest. If the owners agree to go electric, that’s when Liu steps in.

There’s no established name for what Liu does. “It’s not a home improvement business, it’s not an energy efficiency business, it’s not an HVAC business,” she told me. “It’s about putting together a tight live production.” An apt title would be “electrification contractor” — one of the few, if not the only one of her kind operating in the New York area.

Anyone who has tried to electrify even just one appliance in their home has probably wished they could hire someone like Liu. Between finding an available and trustworthy contractor, navigating quotes and equipment choices, and managing ballooning costs, the process is often frustrating and confusing. It’s a major time commitment, not to mention a big capital investment — not a winning formula for mass adoption.

Liu doesn’t offer her services to just any homeowner, though. She only takes on jobs that come through contracts with utilities and government agencies like the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, or NYSERDA. Having ConEd’s backing is actually one of the major benefits Liu brings to the work. It means she’s held to stringent standards of performance. Her business fronts the full cost of every Electric Advantage project, putting up tens of thousands of dollars for parts and labor, and only gets paid back by the utility after she demonstrates she’s met every requirement. Engineers check her design choices on the front end and the installations on the back end. A missing anti-tip bracket on a stove once almost cost her an entire $100,000 job, she told me.

Liu is the first to admit that all of this is a huge headache and a tough business model. She also fundamentally believes in this being utility-backed work. When a homeowner pursues a project on their own, the oversight is only as strong as their own ability to vet contractors and manage the job — which, with limited time, information, and leverage in the market, is likely not nearly as strong as Liu’s.

“My conviction is, for the middle class to thrive, we need to have a lot of things that are expensive to do and complex to do to become utilities,” Liu said. “That’s my hypothesis since I was 22.”

In the climate world, a lot of advocates and experts also believe that a utility-run program like Electric Advantage is the key to unlocking an all-electric future, although for slightly different reasons. When random individual homeowners decide to electrify, a shrinking number of remaining gas customers have to pay to maintain the entire pipeline system. If utilities instead strategically prune the gas system while helping customers go electric, the theory goes, it can reduce costs for remaining gas customers while also creating sustained demand for heat pump retrofits. This would help build the workforce necessary to perform them and create economies of scale.

The problem is, ConEd has 4,400 miles of gas mains. In just over two years of running Electric Advantage, the utility has retired about half of one mile. If the program, or similar ones at other New York utilities, were ever to scale from converting about a dozen buildings a year to taking on the whole state, it would need a lot more Julie Lius. ConEd has a small network of contractors who take on projects with more limited scopes, but Liu is the only one doing whole-home decarbonization.

“It’s high capex deployment of complex work in the field, and you have to have people who go into people’s homes and not piss them off,” said Liu. “That’s a very unique business.”

Liu is not exactly a known figure in the world of building electrification. She’s not on social media or otherwise broadcasting her accomplishments or policy views. You won’t find her headlining clean energy panels or on the boards of nonprofits. But Liu has been quietly leading building electrification in the New York area for nearly a decade. Her early belief in heat pumps and determination to bring them to the New York market helped lay the foundation for future programs in the state.

Long before all of this, Liu was a Taiwanese immigrant growing up in Hacienda Heights, Los Angeles. Her family moved to California from Taipei in 1983, just before she entered seventh grade. Liu told me she “did all the good, dutiful-daughter things.” Her family owned a small furniture manufacturing business, and she went to college at Carnegie Mellon for business and industrial design with the intention of helping her dad produce “more inspiring furniture than colonial reproductions.”

Then her education at Carnegie Mellon took her in a different direction. The programs were built around “productivity, process orientation, efficiency, build it cheaper, faster — it’s all about, can you get things done?” She developed an appreciation for utilities, in a broad sense — for how much of the economy was built around “serving more and more people at scale, and serving them better things.”

When she graduated in the mid-1990s, Liu broke the news to her parents that she wanted to get into telecommunications — the hot field at the time. She initially thought she wanted to work at the Federal Communications Commission, but some early mentors warned her that she wasn’t suited for government work and connected her with a job at DirectTV. “You’re too eager to get things done, you’ll be banging your head against the wall,” she recalled being told at the time. “Go to the private sector.”

She went on to spend the next 15-odd years working in satellite television in New York, with a brief interlude starting a software-as-a-service company with an ex-boyfriend that was a little too ahead of its time, according to Liu. She was successful in the industry, but she wasn’t very happy, she told me. She felt like she was “growing couch potatoes.”

By 2014, after a few zigs and zags — business school, a stint at an online real estate startup in Luxembourg — Liu found herself back in New York, unemployed, and spending a lot of her time trying to fix up the rat-infested Brooklyn brownstone she owned. The building had an oil-burning heating system that was draining her bank account. She wanted to install minisplit heat pumps, which were everywhere back in Taiwan, but at the time nobody was really doing that in New York.

In early 2016, still unemployed and living off savings and tenant rent, Liu reached out to the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, or NYSERDA, to ask about incentives for minisplits, and got connected to a consulting firm called the Levy Partnership that was putting together a proposal for the agency’s first-ever heat pump pilot project. The company told her that brownstones were too difficult and expensive, though, and that it was planning to propose doing the pilot in just a couple of mobile homes on Long Island.

Liu was peeved. Statistically that wouldn’t have even constituted a demonstration, she told me. “That’s not even an alpha in the world of where I came from, satellite communications.” She made a bet with the firm. It was a Thursday. If she could get a bunch of her neighbors to sign letters of interest in the pilot by Monday, she told the company, then “you’re gonna copy and paste that trailer park proposal and say there’s gonna be one for brownstones.”

Needless to say, she got the letters. But Liu didn’t just get the Levy Partnership to expand its proposal or to include her brownstone in the pilot. She convinced it to hire her to help implement the projects. She had looked up the census data on home heating and saw that about half the boilers in the New York City area used expensive heating oil. “I was like, there’s the money,” she told me. She saw that people could lower their bills by switching to heat pumps, while also getting access to better cooling in the summertime. “The business opportunity was just like when I got into satellite, right? It was a transition,” she said.

A week after she and the firm co-submitted their proposal to NYSERDA, Liu incorporated her new company under the name Centsible House. (Her business now goes by the name Carta Electric Homes.) NYSERDA awarded the team the funding a few months later, and by March 2017 they were executing agreements with homeowners to participate. The pilot ran for two years and installed heat pumps in 20 homes throughout Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and Long Island, including Liu’s brownstone. Learnings from those projects informed the development of New York’s statewide Clean Heat program, a partnership between utilities and the state that launched in 2020, offering rebates for heat pumps. Liu was “patient zero,” she told me.

After that, NYSERDA as well as ConEd and another local utility, National Grid, hired Liu for other demonstration projects and heat pump programs. She racked up more than a dozen trainings and certifications from the Building Performance Institute, the Environmental Protection Agency, and various equipment manufacturers, developing expertise in building envelopes, heat pumps, refrigerant systems, and health and safety.

In this piecemeal way, Liu created the job of the electrification contractor from the ground up. By the time ConEd was preparing to launch the Electric Advantage program, Liu had the only contracting business in the area that was essentially purpose-built to take it on.

On a recent Thursday morning in Croton, New York, a suburb of New York City, the show was behind schedule. Liu and I pulled up to a two-family house at the top of a hill to oversee what was supposed to be the “grand finale” day of an Electric Advantage-funded retrofit.

In this case, workers had already put in a new electrical panel, minisplit heat pumps, and a heat pump clothes dryer. Now, electricians would rewire the kitchens with 220-volt outlets for new induction stoves, while a father and son duo of plumbers would put heat pump water heaters in the basement, and a weatherization team would spray insulation around the perimeter of the basement roof and attic floor.

While still sitting in the driveway, Liu called PC Richard, the appliance store, to check on the stove delivery, but the sales rep on the other end was confused — she didn’t have anything scheduled. Liu kept her cool and worked it out, setting a new delivery date for the following day. She turned to me, with sympathy, to let me know this meant I wouldn’t get the denouement she had promised — the cutting and capping of the gas line. She made sure the plumbers could come back on Friday to finish the job.

The planning for this project began many months before, with a knock on the door from a man named Mark Brescia, who manages Electric Advantage for ConEd. Brescia does all the initial outreach, making house calls, phone calls, and sending emails, trying to sell homeowners on the idea. Part of the challenge is that in most cases, unless 100% of the buildings served by a given gas main agree to participate, the company can’t move forward because it won’t be able to retire the pipe. The majority of successful Electric Advantage projects to date have replaced gas mains that were serving a single building.

The company doesn’t sell the program to customers by talking about climate change or emissions. Instead, Brescia explains that the money that would have been spent digging up a gas pipeline could instead be used to buy them brand new appliances. “Customers are excited about the opportunity to make their everyday living more comfortable,” Brescia told me when I asked what the biggest selling point tended to be. They also “no longer worry about having to spend money to replace equipment when it fails.” If the building owner is interested, the next step is for them to schedule a visit from Liu, who does a site evaluation and budgets the job.

Survey data collected by ConEd shows that the most common reason customers decline to participate is a preference for gas cooking. The second is fear of higher electric bills. ConEd makes no guarantees to customers that their overall bills will go down if they participate, but by pairing the new appliances with air sealing and insulation, it tries to ensure the homes will run as efficiently as possible. Liu does her best to provide customer education, walking them through how to operate their heat pumps correctly — running the devices consistently, rather than turning them up and down or on and off, which uses more energy. Customers can also opt in to a special ConEd electricity rate that can save heat pump customers money if they run their systems this way.

“Many customers are still learning about the superior performance and convenience these technologies offer,” Brescia said. But there are also other bottlenecks to expanding the Electric Advantage program. Under New York law, if customers want to keep their gas service, ConEd must oblige them. So unless and until legislators change this “duty to serve,” the program will be hamstrung by customers who turn it down.

The program also currently only targets replacement of leak-prone “radial” mains — pipes that connect to the wider gas distribution system on just one end — as these can be removed without affecting system safety or reliability. The path to expanding it beyond these is uncertain because, as currently structured, that would start to put an untenable burden on customers.

Whether the money goes to a new gas main or a home electrification project, it comes from ConEd’s gas ratepayers through their bills. Whenever ConEd identifies a new batch of mains that meet the program’s specifications, it must submit a benefit-cost analysis to state regulators for approval to pursue the projects before it can begin reaching out to homeowners. In the most recent batch submitted to regulators, for example, replacing the 26 mains identified would have cost nearly $8 million, while the estimated cost of electrifying the buildings served was around $6 million, plus another $1 million in electric system upgrades. The latter is obviously a better deal for customers, even if, as an incentive, ConEd earns back part of the difference as a bonus — also paid for by customers.

Since gas customers pay for the program, it doesn’t totally solve the problem of a shrinking number of customers covering these major investments, even if they are spending less than they otherwise would. And once the most cost-effective projects get taken care of, the expense of electrification will be harder to justify.

Growing the program also depends on having more contractors like Liu to implement it, Brescia told me. Liu has a proven track record of coordinating multiple trades, upholding standards, and educating customers. “Delivering an exceptional customer experience is essential to building trust and driving widespread adoption of electric appliances,” he said.

Throughout the day that I spent with her, Liu vacillated over the question of whether she should or even could expand her business. Working alone enables her to keep costs down, she told me. “I cannot afford to hire additional people,” she said, “because every extra bit of cash flow I end up generating as a profit gets fed to more jobs” — that is, more electrification projects. She also doesn’t want to take on a bunch of high interest debt in order to front more capital to take on more projects.

At other points, she talked about scaling as both important and inevitable. She believes in whole-home electrification — both as a climate solution and as a way to change people’s lives for the better — and wants to see other entrepreneurs like her, especially women, be able to pursue this as a career. She already gets more job leads than she’s able to pursue. She’s starting to think about other fundraising options, such as finding private investors.

Liu also recently started working with a Columbia University masters student to develop software that would help manage and automate all of the “mind-numbing, insane amounts of reporting, submissions, and invoicing” she has to do. Although she already does all of the administrative work digitally, the process has only gotten more arduous as the various programs and companies she works with frequently change what and how she has to report back, whether due to shifting policies or just a round of McKinsey-ification. This is part of what prevents her from being able to take on more work, since all the bureaucratic overhead makes it harder for her to fully close a job and get paid.

Although it’s still very early in the process, her hope is that this kind of software solution could also make it easier for others to get into the field.

“I actually really think this is a very suitable career for every eight-year-old little girl who wants a Barbie’s dream house,” she told me. “If every woman can run a $10 million electrification business, it’d be great. I think we’ll get a lot more done.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

This week is light on the funding, heavy on the deals.

This week’s Funding Friday is light on the funding but heavy on the deals. In the past few days, electric carmaker Rivian and virtual power plant platform EnergyHub teamed up to integrate EV charging into EnergyHub’s distributed energy management platform; the power company AES signed 20-year power purchase agreements with Google to bring a Texas data center online; and microgrid company Scale acquired Reload, a startup that helps get data centers — and the energy infrastructure they require — up and running as quickly as possible. Even with venture funding taking a backseat this week, there’s never a dull moment.

Ahead of the Rivian R2’s launch later this year, the EV-maker has partnered with EnergyHub, a company that aggregates distributed energy resources into virtual power plants, to give drivers the opportunity to participate in utility-managed charging programs. These programs coordinate the timing and rate of EV charging to match local grid conditions, enabling drivers to charge when prices are low and clean energy is abundant while avoiding periods of peak demand that would stress the distribution grid.

As Seth Frader-Thompson, EnergyHub’s president, said in a statement, “Every new EV on the road is a win for drivers and the environment, and by managing charging effectively, we ensure this growth remains a benefit for the grid as well.”

The partnership will fold Rivian into EnergyHub’s VPP ecosystem, giving the more than 150 utilities on its platform the ability to control when and how participating Rivian drivers charge. This managed approach helps alleviate grid stress, thus deferring the need for costly upgrades to grid infrastructure such as substations or transformers. Extending the lifespan of existing grid assets means lower electricity costs for ratepayers and more capacity to interconnect new large loads — such as data centers.

Google seems to be leaning hard into the “bring-your-own-power” model of data center development as it looks to gain an edge in the AI race.

The latest evidence came on Tuesday, when the power company and utility operator AES announced a partnership with the hyperscaler to provide on-site power for a new data center in Texas. signing 20-year power purchase agreements. AES will develop, own, and operate the generation assets, as well as all necessary electricity infrastructure, having already secured the land and interconnection agreements to bring this new power online. The data center is set to begin operations in 2027.

As of yet, neither company has disclosed the exact type of energy infrastructure that AES will be building, although Amanda Peterson Corio, Google’s head of data center energy, said in a press release that it will be “clean.”

“In partnership with AES, we are bringing new clean generation online directly alongside the data center to minimize local grid impact and protect energy affordability,” she said.

This announcement came the same day the hyperscaler touted a separate agreement with the utility Xcel Energy to power another data center in Minnesota with 1.6 gigawatts of solar and wind generation and 300 megawatts of long-duration energy storage from the iron-air battery startup Form Energy.

The microgrid developer Scale has acquired Reload, a “powered land” startup founded in 2024, for an undisclosed sum. What is “powered land”? Essentially, it’s land that Reload has secured and prepared for large data centers customers, obtaining permits and planning for onsite energy infrastructure such that sites can be energized immediately. This approach helps developers circumvent the years-long utility interconnection queue and builds on Scale’s growing focus on off-grid data center projects, as the company aims to deliver gigawatts of power for hyperscalers in the coming years powered by a diverse mix of sources, from solar and battery storage to natural gas and fuel cells.

Early last year, the Swedish infrastructure investor EQT acquired Scale. The goal, EQT said, was to enable the company “to own and operate billions of dollars in distributed generation assets.” At the time of the acquisition, Scale had 2.5 gigawatts of projects in its pipeline. In its latest press release the company announced it has secured a multi-hundred-megawatt contract with a leading hyperscaler, though it did not name names.

As Jan Vesely, a partner at EQT said in a statement, “By bringing together Reload’s campus development capabilities, Scale’s proven islanded power operating platform, and EQT’s deep expertise across energy, digital infrastructure and technology, we are supporting a more integrated approach to delivering power for next-generation digital infrastructure today.”

Not to say there’s been no funding news to speak of!

As my colleague Alexander C. Kaufman reported in an exclusive on Thursday, fusion company Shine Technologies raised $240 million in a Series E round, the majority of which came from biotech billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong. Unlike most of its peers, Shine isn’t gunning to build electricity-generating reactors anytime soon. Instead, its initial focus is producing valuable medical isotopes — currently made at high cost via fission — which it can sell to customers such as hospitals, healthcare organizations, or biopharmaceutical companies. The next step, Shine says, is to scale into recycling radioactive waste from spent fission fuel.

“The basic premise of our business is fusion is expensive today, so we’re starting by selling it to the highest-paying customers first,” the company’s CEO, Greg Piefer told Kaufman, calling electricity customers the “lowest-paying customer of significance for fusion today.”

On the solar siege, New York’s climate law, and radioactive data center

Current conditions: A rain storm set to dump 2 inches of rain across Alabama, Tennessee, Georgia, and the Carolinas will quench drought-parched woodlands, tempering mounting wildfire risk • The soil on New Zealand’s North Island is facing what the national forecast called a “significant moisture deficit” after a prolonged drought • Temperatures in Odessa, Texas, are as much as 20 degrees Fahrenheit hotter than average.

For all its willingness to share in the hype around as-yet-unbuilt small modular reactors and microreactors, the Trump administration has long endorsed what I like to call reactor realism. By that, I mean it embraces the need to keep building more of the same kind of large-scale pressurized water reactors we know how to construct and operate while supporting the development and deployment of new technologies. In his flurry of executive orders on nuclear power last May, President Donald Trump directed the Department of Energy to “prioritize work with the nuclear energy industry to facilitate” 5 gigawatts of power uprates to existing reactors “and have 10 new large reactors with complete designs under construction by 2030.” The record $26 billion loan the agency’s in-house lender — the Loan Programs Office, recently renamed the Office of Energy Dominance Financing — gave to Southern Company this week to cover uprates will fulfill the first part of the order. Now the second part is getting real. In a scoop on Thursday, Heatmap’s Robinson Meyer reported that the Energy Department has started taking meetings with utilities and developers of what he said “would almost certainly be AP1000s, a third-generation reactor produced by Westinghouse capable of producing up to 1.1 gigawatts of electricity per unit.”

Reactor realism includes keeping existing plants running, so notch this as yet more progress: Diablo Canyon, the last nuclear station left in California, just cleared the final state permitting hurdle to staying open until 2030, and possibly longer. The Central Coast Water Board voted unanimously on Thursday to give the state’s last nuclear plant a discharge permit and water quality certification. In a post on LinkedIn, Paris Ortiz-Wines, a pro-nuclear campaigner who helped pass a 2022 law that averted the planned 2025 closure of Diablo Canyon, said “70% of public comments were in full support — from Central Valley agricultural associations, the local Chamber of Commerce, Dignity Health, the IBEW union, district supervisors, marine meteorologists, and local pro-nuclear organizations.” Starting in 2021, she said, she attended every hearing on the bill that saved the plant. “Back then, I knew every single pro-nuclear voice testifying,” she wrote. “Now? I’m meeting new ones every hearing.”

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. It was a year of record solar deployments, it was a year of canceled solar megaprojects, choked-off permits, and desperate industry pleas to Congress for help. But the solar industry’s political clouds may be parting. The Department of the Interior is reviewing at least 20 commercial-scale projects that E&E News reported had “languished in the permitting pipeline” since Trump returned to office. “That includes a package of six utility-scale projects given the green light Friday by Interior Secretary Doug Burgum to resume active reviews, such as the massive Esmeralda Energy Center in Nevada,” the newswire reported, citing three anonymous career officials at the agency.

Heatmap’s Jael Holzman broke the news that the project, also known as Esmeralda 7, had been canceled in October. At the time, NextEra, one of the project’s developers, told her that it was “committed to pursuing our project’s comprehensive environmental analysis by working closely with the Bureau of Land Management.” That persistence has apparently paid off. In a post on X linking to the article, Morgan Lyons, the senior spokesperson at the Solar Energy Industries Association, called the change “quite a tone shift” with the eyes emoji. GOP voters overwhelmingly support solar power, a recent poll commissioned by the panel manufacturer First Solar found. The MAGA coalition has some increasingly prominent fans. As I have covered in the newsletter, Katie Miller, the right-wing influencer and wife of Trump consigliere Stephen Miller, has become a vocal proponent of competing with China on solar and batteries.

Get Heatmap AM directly in your inbox every morning:

MP Materials operates the only active rare earths mine in the United States at California’s Mountain Pass. Now the company, of which the federal government became the largest shareholder in a landmark deal Trump brokered earlier this year, is planning a move downstream in the rare earths pipeline. As part of its partnership with the Department of Defense, MP Materials plans to invest more than $1 billion into a manufacturing campus in Northlake, Texas, dedicated to making the rare earth magnets needed for modern military hardware and electric vehicles. Dubbed 10X, the campus is expected to come online in 2028, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

New York’s rural-urban divide already maps onto energy politics as tensions mount between the places with enough land to build solar and wind farms and the metropolis with rising demand for power from those panels and turbines. Keeping the state’s landmark climate law in place and requiring New York to generate the vast majority of its power from renewables by 2040 may only widen the split. That’s the obvious takeaway from data from the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority. In a memo sent Thursday to Governor Kathy Hochul on the “likely costs of” complying with the law as it stands, NYSERDA warned that the statute will increase the cost of heating oil and natural gas. Upstate households that depend on fossil fuels could face hikes “in excess of $4,000 a year,” while New York City residents would see annual costs spike by $2,300. “Only a portion of these costs could be offset by current policy design,” read the memo, a copy of which City & State reporter Rebecca C. Lewis posted on X.

Last fall, this publication’s energy intelligence unit Heatmap Pro commissioned a nationwide survey asking thousands of American voters: “Would you support or oppose a data center being built near where you live?” Net support came out to +2%, with 44% in support and 42% opposed. Earlier this month, the pollster Embold Research ran the exact same question by another 2,091 registered voters across the country. The shift in the results, which I wrote about here, is staggering. This time just 28% said they would support or strongly support a data center that houses “servers that power the internet, apps, and artificial intelligence” in their neighborhood, while 52% said they would oppose or strongly oppose it. That’s a net support of -24% — a 26-point drop in just a few months.

Among the more interesting results was the fact that the biggest partisan gap was between rural and urban Republicans, with the latter showing greater support than any other faction. When I asked Emmet Penney at the right-leaning Foundation for American Innovation to make sense of that for me, he said data centers stoke a “fear of bigness” in a way that compares to past public attitudes on nuclear power.

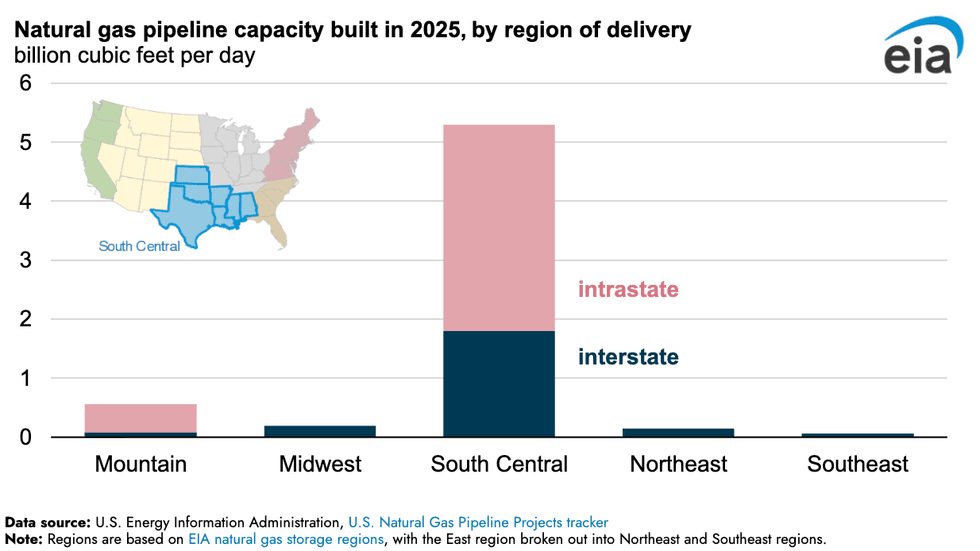

Gas pipeline construction absolutely boomed last year in one specific region of the U.S. Spanning Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama, the so-called South Central bloc saw a dramatic spike in intrastate natural gas pipelines, more than all other regions combined, per new Energy Information Administration data. It’s no mystery as to why. The buildout of liquified natural gas export terminals along the Gulf coast needs conduits to carry fuel from the fracking fields as far west as the Texas Permian.

Rob sits down with Jane Flegal, an expert on all things emissions policy, to dissect the new electricity price agenda.

As electricity affordability has risen in the public consciousness, so too has it gone up the priority list for climate groups — although many of their proposals are merely repackaged talking points from past political cycles. But are there risks of talking about affordability so much, and could it distract us from the real issues with the power system?

Rob is joined by Jane Flegal, a senior fellow at the Searchlight Institute and the States Forum. Flegal was the former senior director for industrial emissions at the White House Office of Domestic Climate Policy, and she has worked on climate policy at Stripe. She was recently executive director of the Blue Horizons Foundation.

Shift Key is hosted by Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Here is an excerpt from their conversation:

Robinson Meyer: What’s interesting is the scarcity model is driven by the fact that ultimately rate payers that is utility customers are where the buck stops, and so state regulators don’t want utilities to overbuild for a given moment because ultimately it is utility customers — it’s people who pay their power bills — who will bear the burden of a utility overbuilding. In some ways, the entire restructured electricity market system, the entire shift to electricity markets in the 90s and aughts, was because of this belief that utilities were overbuilding.

And what’s been funny is that, what, we started restructuring markets around the year 2000. For about five or six or seven years. Wall Street was willing to finance new electricity. I mean, I hear two stories here — basically it’s another place where I hear two stories, and I think where there’s a lot of disagreement about the path forward on electricity policy, in that I’ve heard a story that, basically, electricity restructuring starts in the late 90s you know year 2000, and for five years, Wall Street is willing to finance new power investment based entirely on price risk based entirely on the idea that market prices for electricity will go up. Then three things happen: The Great Recession, number one, wipes out investment, wipes out some future demand.

Number two, fracking. Power prices tumble, and a bunch of plays that people had invested in, including then advanced nuclear, are totally out of the money suddenly. Number three, we get electricity demand growth plateaus, right? So for 15 years, electricity demand plateaus. We don’t need to finance investments into the power grid anymore. This whole question of, can you do it on the back of price risk? goes away because electricity demand is basically flat, and different kinds of generation are competing over shares and gas is so cheap that it’s just whittling away.

Jane Flegal: But this is why that paradigm needs to change yet again. Like ,we need to pivot to like a growth model where, and I’m not, again —

Meyer: I think what’s interesting, though, is that Texas is the other counterexample here. Because Texas has had robust load growth for years, and a lot of investment in power production in Texas is financed off price risk, is financed off the assumption that prices will go up. Now, it’s also financed off the back of the fact that in Texas, there are a lot of rules and it’s a very clear structure around finding firm offtake for your powers. You can find a customer who’s going to buy 50% of your power, and that means that you feel confident in your investment. And then the other 50% of your generation capacity feeds into ERCOT. But in some ways, the transition that feels disruptive right now is not only a transition like market structure, but also like the assumptions of market participants about what electricity prices will be in the future.

Flegal: Yeah, and we may need some like backstop. I hear the concerns about the risks of laying early capital risks basically on rate payers in the frame of growth rather than scarcity. But I guess my argument is just there’s ways to deal with that. Like we could come up with creative ways to think about dealing with that. And I’m not seeing enough ideation in that space, which — I would like, again, a call for papers, I guess — that I would really like to get a better handle on.

The other thing that we haven’t talked about, but that I do think, you know, the States Forum, where I’m now a senior fellow, I wrote a piece for them on electricity affordability several months ago now. But one of the things that doesn’t get that much attention is just like getting BS off of bills, basically. So there’s like the rate question, but then there’s the like, what’s in a bill? And like, what, what should or should not be in a bill? And in truth, you know, we’ve got a lot of social programs basically that are being funded by the rate base and not the tax base. And I think there are just like open questions about this — whether it’s, you know, wildfire in California, which I think everyone recognizes is a big challenge, or it’s efficiency or electrification or renewable mandates in blue states. There are a bunch of these things and it’s sort of like there are so few things you can do in the very near term to constrain rate increases for the reasons we’ve discussed.

You can find a full transcript of the episode here.

Mentioned:

Cheap and Abundant Electricity Is Good, by Jane Flegal

From Heatmap: Will Virtual Power Plants Ever Really Be a Thing?

Previously on Shift Key: How California Broke Its Electricity Bills and How Texas Could Destroy Its Electricity Market

This episode of Shift Key is sponsored by …

Accelerate your clean energy career with Yale’s online certificate programs. Explore the 10-month Financing and Deploying Clean Energy program or the 5-month Clean and Equitable Energy Development program. Use referral code HeatMap26 and get your application in by the priority deadline for $500 off tuition to one of Yale’s online certificate programs in clean energy. Learn more at cbey.yale.edu/online-learning-opportunities.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.