You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Why permitting reform could break the political alliance that produced America’s most significant climate law

The U.S. climate coalition is under serious strain.

The tension has been brought to a head by last month’s debt-ceiling compromise, which enacted a variety of reforms to the National Environmental Policy Act and exempted the long-debated Mountain Valley Pipeline from federal environmental review. While environmental groups have decried the concessions as “a colossal error … that sacrifices the climate,” clean-energy trade groups are praising them “an important down payment on much-needed reforms.” This gulf now threatens to disintegrate the political alliance that, less than a year ago, won the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), its most tangible accomplishment and by far the country’s most significant climate law.

The differences over permitting reform aren’t just a disagreement about tactics. Rather, they reflect fundamental changes within three of the most important factions within the climate coalition — the environmental movement, the clean energy industry, and the Washington-centric group I’ve termed the green growthers. Facing these changes and their implications is critical to preserving the political foundations of federal climate action.

Ever since passage of the IRA unlocked massive fiscal resources for decarbonization, the climate coalition has been split on how best to put that money to work. While nearly everyone recognizes the need to substantially increase the pace at which clean energy infrastructure gets deployed, division centers on the question of permitting reform. To even name the debate is to invoke a factional diagnosis: the view that environmental laws are hobbling decarbonization by preventing clean energy infrastructure from getting built quickly enough — or even at all. This perspective has rapidly gained momentum across a bipartisan community that includes self-styled centrists within the climate coalition.

Permitting reform is unraveling the climate coalition because it reawakens a fundamental, unresolved disagreement over how to decarbonize. Its timing adds to these tensions: bipartisan legislation to curtail national environmental law has arrived, not accidentally, just as the clean energy industry has become most capable of splitting from the broader climate coalition that helped create it.

Get one great climate story in your inbox every day:

The oldest faction in today’s climate coalition, and the most diffuse, is the environmental movement. Its mainstream wing has roots in the principles of preservation, and its largest organizations have spent multiple generations fighting for clean air and water, and ecologically healthy lands and species.

Its environmental justice wing, by contrast, emerged as racial justice activists combined civil-rights and environmental-protection principles to address historically unequal pollution burdens that have concentrated health risks and environmental damages in disempowered communities of color. Only in the last few years, after decades of discoordination, disinterest, and exclusion, have preservationist institutions become more attentive to the legacy of environmental racism. The movement has now coalesced, however incompletely, around a broader and more inclusive environmental vision.

Though preservationist and environmental-justice approaches can still lead to different priorities, the new environmental movement is at its most unified when it opposes fossil fuel production. The movement’s history of civil disobedience and legal combat have taught it to keep fossil fuels in its crosshairs — not only because of the social and environmental harm fossil fuel projects cause, but also because fights against fossil fuels mobilize the public, clarify the stakes, and yield tangible improvements for local communities and environments.

Though both wings of the environmental movement fought hard for the IRA, the law does almost nothing to directly constrain fossil fuel production. Instead, the IRA largely aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions not by preventing those emissions, but rather by boosting the production and use of low-carbon energy — along with generous subsidies for storing carbon dioxide, often in conjunction with oil production or fossil fuel combustion. Accordingly, the environmental movement has redoubled its efforts to pair the law’s clean energy subsidies with new fossil fuel restrictions.

The environmental movement’s discomfort with a subsidies-only approach to decarbonization is probably better known than the shifting politics of the clean energy industry. As the new environmental movement has coalesced, clean energy has matured into a fully-fledged industry, both in the U.S. and around the world. Until the past few years, the nascent clean energy industry wielded little political muscle, depending instead on the political support and lobbying assistance of environmental groups. Not that long ago, renewable energy was more expensive, less familiar to regulators, and supported by fewer subsidies than fossil energy systems. As a result, clean energy companies depended heavily on the environmental movement’s political support to survive and grow.

Over the past half a decade, technological progress and policy victories achieved in coalition with the environmental movement have vaulted key technologies like wind, solar, and batteries into commercial maturity. Those gains are now locked in. The IRA provides at least 10 years of new federal clean energy tax credits, ending the boom-and-bust cycle of short-term extensions that held the clean energy industry together for most of the previous two decades. With falling costs and fiscal tailwinds, the clean energy industry no longer relies on the environmental movement’s lobbying muscle for commercial success.

The clean energy industry’s maturation has led to more profound differences with the environmental movement that eclipse a simple re-alignment in relative power. As the clean energy industry has grown, it has come to share the fossil energy industry’s preference for more permissive regulatory regimes and fewer environmental protections. In the pre-commercial era, climate-conscious jurisdictions like California drove clean energy development through supportive environmental policy. In recent years, though, the clean energy industry has grown faster and profited more in places like Texas, and for the same reason the fossil fuel industry has: because Texas offers open markets and few restrictions on energy development. As the clean energy industry’s policy priorities have shifted, its growing lobbying apparatus has followed suit, leading groups like the American Clean Power Association to collaborate with fossil fuel companies in pursuit of environmental deregulation.

Activists and policymakers focused on rapid, massive clean energy development make up a third critical faction of the national climate movement. Many in this group work in and around the Biden administration and have come to the climate fight not from the environmental movement, but from other areas such as industrial policy, national defense, some strands of organized labor, and electoral politics. They have brought their prior priorities — job creation, domestic manufacturing, and stable energy prices — to their climate politics. In the wake of the IRA, they remain focused on lowering the remaining barriers to rapid clean energy development.

These often center-left climate actors have only cohered into a distinct faction in the past five years, as enthusiasm for so-called “supply-side progressivism” has given them a common language with which to articulate a set of climate solutions founded on proactive government support for private reindustrialization. For some green growthers, deregulation is a necessary precondition to decarbonization, and since many also believe that clean energy will — with the IRA’s help — outcompete fossil fuels, they see fewer risks to reforming environmental law than the environmental movement does.

In part, the conflict over permitting reform has grown bitter because the term gets used to refer to many different policy proposals. Depending on the speaker and the audience, it can mean sweeping changes to how environmental laws govern new infrastructure projects; tailored tweaks to environmental review; more resources to strengthen administrative capacity and expedite permitting reviews; or changes to the process for building transmission lines and connecting power plants to the grid. This tangle of meanings has undermined the climate coalition’s ability to negotiate its internal differences and prioritize consensus solutions to the challenge of rapid clean-energy development.

More fundamentally, though, the environmental movement, the clean energy industry, and the green growthers are clashing over permitting reform because it has forced them to confront their ongoing disagreement about how to achieve decarbonization.

To many in the environmental movement, and especially on the climate left, most permitting reform proposals double down on what they see as a worrying tenet of the IRA: its dependence on competition and market dynamics to slash fossil fuel production. The environmental movement is familiar from long experience with this kind of market thinking, which promises that present development and the damage it entails will eventually unlock future benefits. As the environmental movement as a whole has become more concerned with historical pollution burdens, that bargain looks worse, and less trustworthy, than ever.

Many permitting reform proposals, including the newly-enacted language of the debt-ceiling deal, exacerbate these concerns by targeting the environmental movement’s oldest and most effective legal tools for defeating fossil fuel projects. At the same time, these proposals still omit any of the constraints on fossil fuels that the environmental movement believes necessary for decarbonization.

The environmental movement has responded with deployment-focused proposals of its own that aim to speed clean energy development without weakening environmental law. However, even the most straightforward of these proposals — such as appointing a fifth commissioner to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission — have repeatedly been deprioritized by clean-energy groups and green growthers. In the wake of the debt ceiling deal, which included none of the environmental movement’s reform priorities but substantially weakened environmental review, the movement is mobilized and angry.

To the green growthers, by contrast, rapid decarbonization cannot happen without permitting reform. According to the IRA’s market-decarbonization logic, the best and most politically plausible way to drive fossil fuels out of American energy markets is to displace them with cheaper and more abundant clean energy. At the same time, events such as the gas-price shock of 2021 — and its damage to Biden’s popularity — has reinforced their existing belief that suppressing fossil fuel extraction without first creating massive new clean energy production will risk serious political backlash. This theory of change has led green growthers to be simultaneously sympathetic to the clean energy industry’s deregulatory wishlist, and skeptical of the environmental movement’s focus on constraining fossil fuel production.

These factions’ divergent theories of decarbonization have offered a wedge to those within the climate coalition who believe rapid, effective clean energy development has become incompatible with rigorous environmental and social protections. Anti-coalitional voices, especially within portions of the clean energy industry, increasingly see permitting reform as an opportunity to split the climate coalition, excising the environmental movement from the climate coalition and creating a new, climate-inflected industrial alliance.

Most green growthers understand that such a split would deprive the existing coalition of its popular wing at a critical moment, threatening the political viability of climate progress. Though the growthers believe that the IRA’s clean-energy manufacturing boom will build a powerful new political coalition in favor of decarbonization, that coalition does not yet exist.

Environmental protection, by contrast, is extremely popular across America today, and the environmental movement has repeatedly proven its ability to mobilize public support. Though the clean energy industry no longer needs the environmental movement’s political muscle to turn a profit, the climate coalition as a whole may struggle to maintain political support for decarbonization without it, especially as climate change destabilizes the country’s energy systems and the right continues to oppose rapid decarbonization.

To understand why, you don’t need to look farther than Texas, which is something of a proving ground for the three factions’ competing beliefs about how deregulation may shape decarbonization.

In recent years, Texas provided strong evidence for the clean energy industry’s assertions that, whatever the environmental and social costs, less regulation can speed the deployment of renewable energy. It likewise bolstered green growthers’ claims that cheap, plentiful renewables can displace fossil energy.

But suddenly, Texas is also proving the environmental movement’s counter-argument. The state’s legislature has just created a new set of generous rules and tax subsidies that support new gas-fired power plants while hampering clean energy development. Though state lawmakers are transparently motivated by gas-industry lobbying and culture-war fixations, they have justified the legislation by arguing that Texas’ increasingly unreliable grid needs more gas plants to keep the lights on.

Such claims, however dishonest, will only grow more plausible to many voters as climate-exacerbated disasters and the energy transition itself strain infrastructural systems in the years to come. Without permitting structures or robust state environmental laws, Texan climate activists are ill-equipped to fight a possible new wave of gas plants, and Texas’ future decarbonization is now in peril.

Whereas last year, Texas’ clean energy boom seemed likely to continue driving fossil fuels out of the market and emissions down, now Texas’ new IRA-style subsidies and weak environmental protections look more likely to leave the state with more energy production of all kinds. Though Texas will continue to add clean energy, its decarbonization remains in doubt.

Permitting reform is threatening the national climate coalition because it cuts to the heart of a longstanding philosophical disagreement about what it will take to actually achieve decarbonization. It has arrived as the climate coalition’s major factions are transforming in ways that themselves sharpen the conflict. Good-faith advocates of decarbonization in all camps should be concerned that, in the wake of the debt-ceiling deal, a new round of fractious permitting-reform fights will split the climate coalition into separate camps with irreconcilable theories of climate action.

The result, though ideologically purifying, would be politically disastrous.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Six months in, federal agencies are still refusing to grant crucial permits to wind developers.

Federal agencies are still refusing to process permit applications for onshore wind energy facilities nearly six months into the Trump administration, putting untold billions in energy infrastructure investments at risk.

On Trump’s first day in office, he issued two executive orders threatening the wind energy industry – one halting solar and wind approvals for 60 days and another commanding agencies to “not issue new or renewed approvals, rights of way, permits, leases or loans” for all wind projects until the completion of a new governmental review of the entire industry. As we were first to report, the solar pause was lifted in March and multiple solar projects have since been approved by the Bureau of Land Management. In addition, I learned in March that at least some transmission for wind farms sited on private lands may have a shot at getting federal permits, so it was unclear if some arms of the government might let wind projects proceed.

However, I have learned that the wind industry’s worst fears are indeed coming to pass. The Fish and Wildlife Service, which is responsible for approving any activity impacting endangered birds, and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, tasked with greenlighting construction in federal wetlands, have simply stopped processing wind project permit applications after Trump’s orders – and the freeze appears immovable, unless something changes.

According to filings submitted to federal court Monday under penalty of perjury by Alliance for Clean Energy New York, at least three wind projects in the Empire State – Terra-Gen’s Prattsburgh Wind, Invenergy’s Canisteo Wind, and Apex’s Heritage Wind – have been unable to get the Army Corps or Fish and Wildlife Service to continue processing their permitting applications. In the filings, ACE NY states that land-based wind projects “cannot simply be put on a shelf for a few years until such time as the federal government may choose to resume permit review and issuance,” because “land leases expire, local permits and agreements expire, and as a result, the project must be terminated.”

While ACE NY’s filings discuss only these projects in New York, they describe the impacts as indicative of the national industry’s experience, and ACE NY’s executive director Marguerite Wells told me it is her understanding “that this is happening nationwide.”

“I can confirm that developers have conveyed to me that [the] Army Corps has stopped processing their applications specifically citing the wind ban,” Wells wrote in an email. “As I have understood it, the initial freeze covered both wind and solar projects, but the freeze was lifted for solar projects and not for wind projects.”

Lots of attention has been paid to Trump’s attacks on offshore wind, because those projects are sited entirely in federal waters. But while wind projects sited on private lands can hypothetically escape a federal review and keep sailing on through to operation, wind turbines are just so large in size that it’s hard to imagine that bird protection laws can’t apply to most of them. And that doesn’t account for wetlands, which seem to be now bedeviling multiple wind developers.

This means there’s an enormous economic risk in a six-month permitting pause, beyond impacts to future energy generation. The ACE NY filings state the impacts to New York alone represent more than $2 billion in capital investments, just in the land-based wind project pipeline, and there’s significant reason to believe other states are also experiencing similar risks. In a legal filing submitted by Democratic states challenging the executive order targeting wind, attorneys general listed at least three wind projects in Arizona – RWE’s Forged Ethic, AES’s West Camp, and Repsol’s Lava Run – as examples that may require approval from the federal government under the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act. As I’ve previously written, this is the same law that bird conservation advocates in Wyoming want Trump to use to reject wind proposals in their state, too.

The Fish and Wildlife Service and Army Corps of Engineers declined to comment after this story's publication due to litigation on the matter. I also reached out to the developers involved in these projects to inquire about their commitments to these projects in light of the permitting pause. We’ll let you know if we hear back from them.

On power plant emissions, Fervo, and a UK nuclear plant

Current conditions: A week into Atlantic hurricane season, development in the basin looks “unfavorable through June” • Canadian wildfires have already burned more land than the annual average, at over 3.1 million hectares so far• Rescue efforts resumed Wednesday in the search for a school bus swept away by flash floods in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa.

The Environmental Protection Agency plans to announce on Wednesday the rollback of two major Biden-era power plant regulations, administration insiders told Bloomberg and Politico. The EPA will reportedly argue that the prior administration’s rules curbing carbon dioxide emissions at coal and gas plants were misplaced because the emissions “do not contribute significantly to dangerous pollution,” per The Guardian, despite research showing that the U.S. power sector has contributed 5% of all planet-warming pollution since 1990. The government will also reportedly argue that the carbon capture technology proposed by the prior administration to curb CO2 emissions at power plants is unproven and costly.

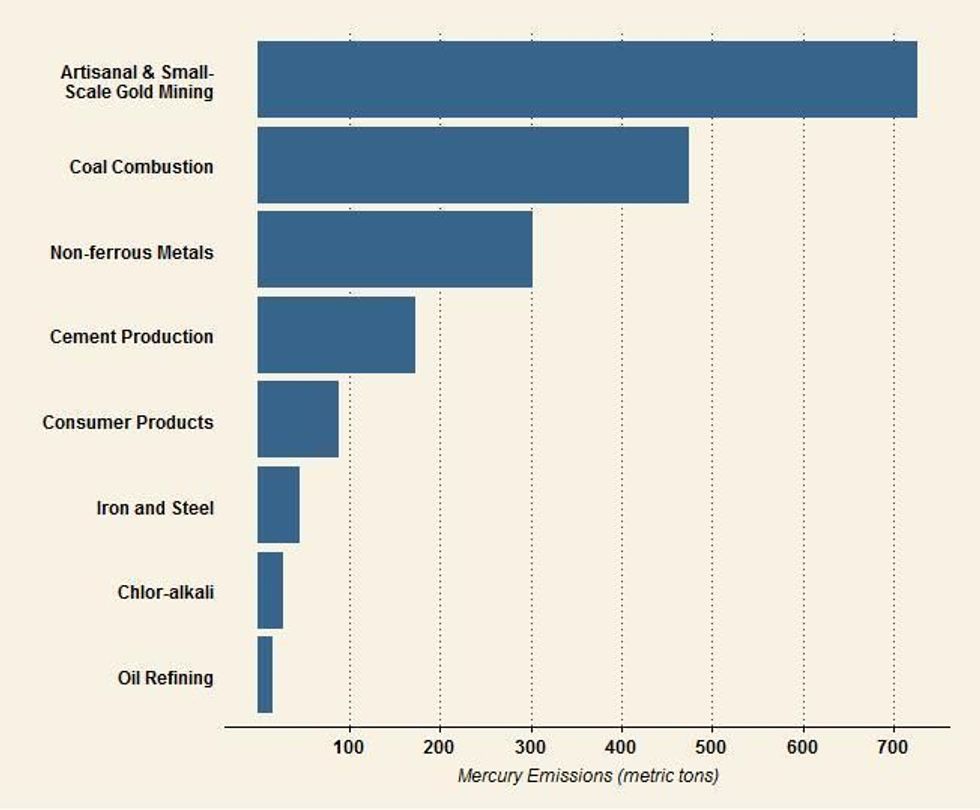

Similarly, the administration plans to soften limits on mercury emissions, which are released by burning coal, arguing that the Biden administration “improperly targeted coal-fire power plants” when it strengthened existing regulations in 2024. Per a document reviewed by The New York Times, the EPA’s proposal will “loosen emissions limits for toxic substances such as lead, nickel, and arsenic by 67%,” and for mercury at some coal power plants by as much as 70%. “Reversing these protections will take lives, drive up costs, and worsen the climate crisis,” Climate Action Campaign Director Margie Alt said in a statement. “Instead of protecting American families, [President] Trump and [EPA Administrator Lee] Zeldin are turning their backs on science and the public to side with big polluters.”

Fervo Energy announced Wednesday morning that it has secured $206 million in financing for its 400-megawatt Cape Station geothermal project in southwest Utah. The bulk of the new funding, $100 million, comes from the Breakthrough Energy Catalyst program.

Fervo’s announcement follows on the heels of the company’s Tuesday announcement that it had drilled its hottest and deepest well yet — at 15,000 feet and 500 degrees Fahrenheit — in just 16 days. As my colleague Katie Brigham reports, Fervo’s progress represents “an all too rare phenomenon: A first-of-a-kind clean energy project that has remained on track to hit its deadlines while securing the trust of institutional investors, who are often wary of betting on novel infrastructure projects.” Read her full report on the clean energy startup’s news here.

The United Kingdom said Tuesday that it will move forward with plans to construct a $19 billion nuclear power station in southwest England. Sizewell C, planned for coastal Suffolk, is expected to create 10,000 jobs and power 6 million homes, The New York Times reports. Sizewell would be only the second nuclear power plant to be built in the UK in over two decades; the country generates approximately 14% of its total electricity supply through nuclear energy. Critics, however, have pointed unfavorably to the other nuclear plant under construction in the UK, Hinkley Point C, which has experienced multiple delays and escalating costs throughout its development. “For those who have followed Sizewell’s progress over the years, there was a glaring omission in the announcement,” one columnist wrote for The Guardian. “What will consumers pay for Sizewell’s electricity? Will it still be substantially cheaper in real terms than the juice that will be generated at Hinkley Point C in Somerset?” The UK additionally announced this week that it has chosen Rolls-Royce as the “preferred bidder” to build the country’s first three small modular nuclear reactors.

The European Union on Tuesday proposed a ban on transactions with Nord Stream 1 and 2 as part of a new package of sanctions aimed at Russia, Bloomberg reports. “We want peace for Ukraine,” the president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, said at a news conference in Brussels. “Therefore, we are ramping up pressure on Russia, because strength is the only language that Russia will understand.” The package would also lower the price cap on Russian oil to $45 a barrel, down from $60 a barrel, von der Leyen said, as well as crack down on Moscow’s “shadow fleet” of vessels used to transport sanctioned products like crude oil. The EU’s 27 member states need to unanimously agree to the package for it to be adopted; their next meeting is on June 23.

The world’s oceans hit their second-highest temperature ever in May, according to the European Union’s Earth observation program Copernicus. The average sea surface temperature for the month was 20.79 degrees Celsius, just 0.14 degrees below May 2024’s record. Last year’s marine heat had been partly driven by El Niño in the Pacific, so the fact that the oceans remain warm in 2025 is alarming, Copernicus senior scientist Julien Nicolas told the Financial Times. “As sea surface temperatures rise, the ocean’s capacity to absorb carbon diminishes, potentially accelerating the build-up of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and intensifying future climate warming,” he said. In some areas around the UK and Ireland, the sea surface temperature is as high as 4 degrees Celsius above average.

The Pacific Island nation of Tonga is poised to become the first country to recognize whales as legal persons — including by appointing them (human) representatives in court. “The time has come to recognize whales not merely as resources but as sentient beings with inherent rights,” Tongan Princess Angelika Lātūfuipeka Tukuʻaho said in comments delivered ahead of the U.N. Ocean Conference in Nice, France.

Microsoft, Amazon, Google, and the rest only have so much political capital to spend.

When Donald Trump first became a serious Presidential candidate in 2015, many big tech leaders sounded the alarm. When the U.S. threatened to exit the Paris Agreement for the first time, companies including Google, Microsoft, Apple, and Facebook (now Meta) took out full page ads in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal urging Trump to stay in. He didn’t — and Elon Musk, in particular, was incensed.

But by the time specific climate legislation — namely the Inflation Reduction Act — was up for debate in 2022, these companies had largely clammed up. When Trump exited Paris once more, the response was markedly muted.

Now that the IRA’s tax credits face clear and present threats, this same story is playing out again. As the Senate makes its changes to the House’s proposed budget bill, tech giants such as Microsoft, Google, Meta, and Amazon are keeping quiet, at least publicly, about their lobbying efforts. Most did not respond to my request for an interview or a statement clarifying their position, except to say they had “nothing to share on this topic,” as Microsoft did.

That’s not to say they have no opinion about the fate of clean energy tax credits. Microsoft, Google, Meta, and Amazon have all voluntarily set ambitious net-zero emissions targets that they’re struggling to meet, largely due to booming data center electricity demand. They’re some of the biggest buyers of solar and wind energy, and are investing heavily in nuclear and geothermal. (On Wednesday morning, Pennsylvania’s Talen Energy announced an expanded power purchase agreement with Amazon, for nearly 2 gigawatts of power through 2042.) All of these energy sources are a whole lot more accessible with tax credits than without.

There’s little doubt the tech companies would prefer an abundant supply of cheap, clean energy. Exactly how much they’re willing to fight for it is the real question.

The answer may come down to priorities. “It’s hard to overstate how much this race for AI has just completely changed the business models and the way that these big tech companies are thinking about investment,” Jeff Navin, co-founder of the climate-focused government affairs firm Boundary Stone Partners, told me. “While they’re obviously going to be impacted by the price of energy, I think they’re even more interested and concerned about how quickly they can get energy built so that they can build these data centers.”

The tech industry has shown much more reluctance to stand up to Trump, period, this time around. As the president has moved from a political outsider to the central figure in the Republican party, hyperscalers have increasingly curried his favor as they advocate against actions that could pose an existential risk to their business — think tighter regulations on the tech sector or AI, or tariffs on key supplies made in Asia.

As Navin put it to me, “When you have a president who has very strong opinions on wind turbines and randomly throws companies’ names in tweets in the middle of the night, do you really want to stick your neck out and take on something that the president views as unpopular if you’ve got other business in front of him that could be more impactful for your bottom line?”

It is undeniably true that the AI-driven data center boom is pushing these companies to look for new sources of clean power. Last week Meta signed a major nuclear deal with Constellation Energy. Microsoft is also partnering with Constellation to reopen Three Mile Island, while Google and Amazon have both announced investments in companies developing small modular reactors. Meta, Google, and Microsoft are also investing in next-generation geothermal energy startups.

But while the companies are eager to tout these partnerships, Navin suspects most of their energy lobbying is now being directed towards efforts such as permitting reform and building out transmission infrastructure. Publicly available lobbying records confirm that these are indeed focus areas, as they’re critical to bringing data centers online quickly, regardless of how they’re powered and whether that power is subsidized. “They’re not going to stop construction on an energy project that has access to electricity just because that electricity is marginally more expensive,” Navin told me. “There’s just too much at stake.”

Tech companies have lobbied on numerous budget, tax, sustainability, and clean energy issues thus far this year. Amazon’s lobbying report is the only one to specifically call out efforts on “renewable energy tax credits,” while Meta cites “renewable energy policy” and Microsoft name-drops the IRA. But there’s no hard and fast standard for how companies describe the issues they’re lobbying on or what they’re looking to achieve. And perhaps most importantly, the reports don’t disclose how much money they allot to each issue, which would illuminate their priorities.

Lobbying can also happen indirectly, via industry groups such as the Clean Energy Buyers Association and the Data Center Coalition. Both have been vocal advocates for preserving the tax credits. The Wall Street Journal recently detailed a lobbying push by the latter — which counts Microsoft, Amazon, Meta, and Google among its most prominent members — that involved meetings with about 30 Republican senators and a letter to Senate Majority Leader John Thune.

DCC didn’t respond to my request for an interview. But CEBA CEO Rich Powell told me, “If we take away these incentives right now, just as we’re getting the rust off the gears and getting back into growth mode for the electricity economy, we’re really concerned about price spikes.”

The leader of another industry group, Advanced Energy United, shared Powell’s concern that passing the bill would mean higher electricity prices. Taking away clean energy incentives would ”fundamentally undercut the financing structure for — let’s be frank — the vast majority of projects in the interconnection queue today,” Harry Godfrey, the managing director of AEU, told me.

Being part of an industry association is by no means a guarantee of political alignment on every issue. Microsoft, Google, Meta, and Amazon are also members of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce — by far the largest lobbying group in the U.S. — which has a long history of opposing climate action and the IRA itself. Apple even left the Chamber in 2009 due to its climate policy stances.

But Powell and Godfrey implied that the tech giants' views are — or at least ought to be — in alignment with theirs. “Many of our members are lobbying independently. Many of them are lobbying alongside us. And then many of them are supporting CEBA to go and lobby on this,” Powell told me, though he wouldn’t reveal what actions any specific hyperscalers were taking.

Godfrey said that AEU’s positions are “certainly reflective of what large energy consumers, notably tech companies, have been working to pursue across a variety of technologies and with applicability to a couple of different types of credits.”

And yet hyperscalers may have already spent a good deal of their political capital fighting for a niche provision in the House’s version of the budget bill, which bans state-level AI regulation for a decade. That would make the AI boom infinitely easier for tech companies, who don’t want to deal with a patchwork of varying regulations, or really most regulations at all.

On top of everything else, big tech in particular is dealing with government-led anti-trust lawsuits, both at home and abroad. Google recently lost two major cases to the Department of Justice, related to its search and advertising business. A final decision is pending regarding the Federal Trade Commission’s antitrust lawsuit against Meta, regarding the company’s acquisition of Instagram and WhatsApp. Not to be outdone, Amazon will also be fighting an antitrust case brought by the FTC next year.

As these companies work to convince the public, politicians, and the courts that they’re not monopolistic rule-breakers, and that AI is a benevolent technology that the U.S. must develop before China, they certainly seem to be relinquishing the clean energy mantle they once sought to carry, at least rhetorically. We’ll know more once all these data centers come online. But if the present is any indication, speed, not green electrons, is the North Star.

Editor’s note: This story has been updated to reflect Amazon’s power purchase agreement with Talen Energy.