You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

The human mind can’t handle this being just a fire.

Almost no city in the country is destroyed more often than Los Angeles. America’s second-biggest city has been flattened, shaken, invaded, subsumed by lava, and calved off into the sea dozens of times on screen over the years; as the filmmaker and critic Thom Andersen has said, “Hollywood destroys Los Angeles because it’s there.”

But, understandably, when this destruction leaps from Netflix to a newscast, it’s an entirely different horror to behold. The L.A. County fires have now collectively burned an area more than twice the size of Manhattan; more than 10,000 businesses and homes that were standing last weekend are now ash. Officially, 10 people have died, but emergency managers have warned the public to brace for more. “It looks like an atomic bomb dropped in these areas. I don’t expect good news, and we’re not looking forward to those numbers,” Los Angeles County Sheriff Robert Luna said in a late Thursday press conference.

The mind gropes for an explanation for this horror — and lands in bizarre places. Much has been made in the past few days of the rampant proliferation of conspiracy theories and rumors about the fires, ranging from the believable to the totally absurd. Alex Jones has claimed the fires are part of a “globalist plot to wage economic warfare and deindustrialize the U.S.” (a theory incoming government official Elon Musk endorsed as “true”). Libs of TikTok and others have said that the Los Angeles Fire Department’s hiring practices emphasizing diversity have left it strapped for personnel to fight the wildfires (Musk endorsed this one, too). President-elect Donald Trump has blamed California Gov. Gavin Newsom for the well-publicized occurrence of dry fire hydrants, citing a “water declaration resolution” that supposedly limited firefighters’ access to water, even though such a thing doesn’t exist. Still others have taken to TikTok to spread claims that the fires were intentionally started to burn rapper and producer Sean “Diddy” Combs’ property and hide criminal evidence that could be used to support sex trafficking and racketeering charges against him (another lie). Mel Gibson even used the disaster as an opportunity to share his thoughts about climate change on The Joe Rogan Podcast (spoiler alert: he doesn’t think it’s real), even as his house in Malibu burned to the ground.

“We need some kind of explanation psychologically, especially if you’re not accustomed to that kind of thing happening,” Margaret Orr Hoeflich, a misinformation scholar, told me of how conspiracy theories spring up during disasters. She added that much of the rhetoric she’s seen — like that some cabal set the fires intentionally — has been used to “explain” other similar disasters, including the wildfire in Lahaina in 2023. (“The Diddy one is really unique,” she allowed.)

It’s convenient to call this the coping mechanism of loons, bad actors, the far right, or people who want to promote a political agenda disingenuously, but left-leaning thinkers aren’t exempt. Posts blaming ChatGPT make important points about AI technologies’ energy and water use, but the fires aren’t “because” of ChatGPT.

I’ve also seen the fires blamed on “forest management,” although the landscape around L.A. isn’t trees; it’s shrubland. “This kind of environment isn’t typically exposed to low intensity, deep, frequent fires creeping through the understory, like many dry forests of the Sierra Nevadas or even Eastern Oregon and Washington,” where the U.S. Forest Service’s history of fire has created the conditions for the high-intensity megafires of today, Max Moritz, a cooperative extension wildfire specialist at U.C. Santa Barbara’s Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, told me earlier this week. The shrublands around L.A., rather, “naturally have long-interval, high-intensity, stand-replacing fires” — that is, fires that level almost all vegetation in an area before new growth begins.

The fires in L.A. are extreme not so much because the landscape hasn’t been managed properly (not to mention that prescribed burns in the steep hillsides and suburbs are challenging and huge liabilities), but rather because we’ve built neighborhoods into a wildland that has burned before and will burn again. But unless your algorithm is tuned to the frequency of climate and weather models, you won’t necessarily find this more complicated narrative on social media.

We should also be precise in how we talk about climate change in relation to the fires. It’s true the fires have an excess of dry vegetative fuels after a wet winter and spring, which germinated lots of new green shoots, followed by a hot, dry summer and delayed start to the rainy season, which burned them to a crisp — classic “see-sawing” between extremes that you can expect to see as the planet warms. But droughts don’t always have a strong climate change signal, and wildfires can be tricky to attribute to global warming definitively. Were the Los Angeles fires exacerbated by our decades of burning fossil fuels? It is pretty safe to say so! But right-wing narratives aren’t the only ones that benefit from an exaggerated posture of certainty.

To state what is hopefully obvious: Being overly confident in attributing a disaster to climate change is not equivalent to denying the reality of climate change, the latter being very much more wrong and destructive than the former. But it’s also true overall that humans, as a species, don’t like ambiguity. Though the careful work of uncovering causes and attributing them can take years, it’s natural to look for simple answers that confirm our worldviews or give us people to blame — especially in the face of a disaster that is so unbelievably awful and doesn’t have a clear end. If there’s a role for the creative mind during all of this, it’s not in jumping to logical extremes; it’s in looking forward, ambitiously and aggressively, to how we can rebuild and live better.

“There’s a lot of finger-pointing going around, and I would just try to emphasize that this is a really complex problem,” Faith Kearns, a water and wildfire researcher at Arizona State University, told me this week. “We have lots of different responsible parties. To me, what has happened requires more of a rethink than a blame game.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The Northeast is in the middle of its first true blizzard in years. That long gap wasn’t because of climate change, though.

Happy blizzard day, Northeast. While you might be (okay, or most definitely are) sick of the snow at this point, take comfort in the fact that this storm is different. It meets the definition of a true blizzard, in which a large amount of snow falls with sustained winds over 35 miles per hour and visibility reduced to less than a quarter of a mile for more than three hours. That’s a mouthful, all of which is to say: Complain away! You’ve earned it!

New York City hasn’t issued a true blizzard warning since 2017 — but that isn’t because of climate change. In fact, big, bad storms like this one might be getting even worse.

I spoke with Colin Zarzycki, an associate professor of Meteorology and Climate Dynamics at Pennsylvania State University, on Monday morning about what we can expect from winter storms in a warming climate. Our conversation has been lightly edited for clarity, and the snow-weary should proceed with caution.

I've read both that blizzards will increase in a warming world because the atmosphere can hold more moisture to make more snow, and also that, because it’s warmer, a lot of the precipitation will fall as rain instead of snow, so the storms will decrease. What does the research actually say?

Let’s back up for one second. Blizzards like we have in the Northeast today are a subset of nor’easters. We also call them mid-latitude or extra-tropical cyclones — you hear people talk about “low pressure,” “bomb cyclones.” At the end of the day, these are synonyms for storms that track up the East Coast of the U.S. and dump a lot of snow, particularly along the major metro corridor.

A blizzard is a special subset, where you have strong winds that blow the snow around. And that’s really problematic, because — have you experienced a lot of snowstorms?

I went to college in Vermont and lived in New York City for 10 years, so I’m familiar with snow.

I ask because, every once in a while, you talk to someone from, like, Miami, and they’re like, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” But during these strong wind events, blowing snow reduces the visibility. That’s very bad for transportation like aviation, but also just driving on highways and roads.

I want to be careful, because there’s been less work done on the wind side of things. The broad consensus is that if you measure nor'easters as a function of their low pressure — which is somewhat analogous to wind speed; they’re not exactly related, but they’re pretty close — there actually doesn’t seem to be a huge shift. For every storm that comes up the East Coast and turns into a bomb that’s blowing 80-mile-an-hour winds, the distribution of the wind looks pretty similar across different climates, whether cooler or warmer.

What you’re referring to about the precipitation: — this is the thing we’re most confident in the science [of]. If you make the very simple argument — which admittedly, our models indicate it is not a bad argument — that if the number of nor’easters that move up the coast stays relatively constant and the intensity of them doesn’t change a lot as measured by wind speed, but if the atmosphere is warmer and can hold more water vapor, then the rates of what’s coming out of the sky essentially increase.

Now if you’re thinking, “Okay, well, that’s snow,” then yes. If you could take this storm and put it in a time machine and move it 50 years from now, and if the atmosphere is 2 degrees [Celsius] warmer, then you’re going to have more precipitation coming out of the sky, all other things being equal.

But you mentioned the other tricky thing that complicates life. When climate scientists think about precipitation in, let’s say, Florida, where it doesn’t snow at all, it generally all just goes one way: It gets warmer, it rains harder. But in the Northeast, we have two things that compete with each other. On the one hand, precipitation increases, as we just discussed. But then obviously, if it warms, more of these storms are likely to produce rain rather than snow.

If you look at just the average number of snowstorms in a warmer world, whether you’re comparing today relative to 1850, or if you’re looking at today and trying to figure out what’s going to happen in 2100, in general, the warmer it gets, the less total snow and the less total number of snowstorms because more of them become rainstorms. The tricky thing is, the decrease really only happens with the weaker snowstorms, the nuisance types.

So if we still get periods in warmer climates where it’s cold enough to snow, and now we’ve turbocharged the atmosphere’s ability to hold moisture by warming, then what we’ve actually done is make it so that when it does snow, it snows harder. In general, we expect to see fewer overall snowstorms when it’s warming, which is very consistent with what we’ve seen in observations in the Northeast U.S. If you look at any major metro area and you plot snow since 1950 it’s generally been on a downslope. But these big blizzard-type storms aren’t going away.

The jury is out as to whether the most, most, most, most extreme snowstorms become a little more extreme. But the big take-home message is that the frequency of big nor’easters isn’t going away, even if the climate warms.

There has been a lot of talk about this being the first blizzard to hit New York City in nine years. I don’t think I can remember a storm quite like this from when I was living there. Is that because this is the most extreme version you’re referring to, that we haven’t seen as often?

If you were to ask someone who has lived in New York City since the 1950s, they would probably tell you that this is a bad snowstorm, but that they’ve seen similar ones. I’m not an expert on the history of New York City weather, but there were a couple of big storms, I think, in the 1970s that were analogous to this, if not a little worse.

What is unique about this storm is that we really haven’t seen one of these tight coastal blizzards this year. We had that storm that came through earlier this year, which also brought a decent amount of snow to New York, but it tracked across the country rather than forming right off the coast and moving up that direction. This one is dragging snow across New York City and Boston; it’s a very classic Northeastern U.S. blizzard.

I think the main aspect is that we have been in a period of luck. We haven’t had these storms as frequently in the past. Some of it goes to that kind of dice-rolling thing with the temperatures. But if you look over the last 10 years, I would assume it’s not that New York City has been nice and sunny and calm in the winter. It’s that you’ve had these wintertime cyclones, but it’s been a lot more rain, or wet, rainy, sleety snow. It hasn’t been cold enough air to really lock in the blizzard conditions.

My understanding is that blizzards are specific atmospheric events in which the wind speed must exceed 35 miles per hour and visibility is limited. How difficult is that to capture in the data? I know from my reporting on tornadoes that it can be really difficult to capture wind events. How do you study this?

The fancy word in climate science is “compound extremes,” and a blizzard is a form of a compound extreme where you have multiple hazards at the same time. Add one layer on top of another, and the more there are, the harder it is to get information out of the data.

Especially in densely populated areas like the Northeastern U.S., blizzards are fairly tricky to look at. When you read the National Weather Service’s definition of a blizzard, it’s like, “It has to be snowing, and you have to have sustained winds, and you have to have decreased visibility.” All of those mean you’re adding layers of complexity to the data.

Tornadoes are a little similar; they’re a discrete phenomenon, and you need specific ingredients to all line up, and there’s also an observation problem. It’s somewhat analogous to blizzards: I could be at JFK Airport in New York, which is right on the ocean. There’s not a lot in the way to slow down the winds. Especially if you have drier snow, it’s very easy for it all to blow around. If I’m a guy working at JFK, I’m saying, “This is really bad, it’s really windy, the snow is coming down, and we can’t see anything. We have to shut everything down.” But put yourself in Midtown or somewhere where you’re surrounded by buildings and a little further away from the ocean, then suddenly the winds might be reduced because you have more obstacles that can slow it down. You’re experiencing the exact same storm, but the impacts are very different.

You said at the beginning that the underlying assumption is that nor’easters will continue at the same rate they’re happening now. Is there anything I should know about the way climate change is impacting those events?

Precipitation is the main thing. There’s been some work on the frequency and track of the storms, and we’ve seen small changes. But we also have a sample-size problem. The more you want to focus on the intense storms, the less you have in your records, and the more challenging it is to tease out what’s going on. That’s one of the reasons I really like models.

So maybe, if you squint, you can see some small changes in the frequency or the track, but it’s on the order of 5% to 10% per year. But the number of nor’easters we actually get in a given winter is not small; depending on how you want to classify it, it’s something like 10 to 15 any given winter. They don’t all produce a lot of snow; some of them go offshore, and if you’re sailing a boat in the middle of the ocean, then you’d be like, yeah, this is a big problem. But generally, we have very high confidence in understanding the precipitation, and decent confidence in understanding how the rain-snow partitioning changes. The winds, I think, are kind of an open question. But we’re talking secondary effects relative to the precipitation for all of them.

Is there anything else I should know about blizzards and climate change?

I do interviews every winter about bomb cyclones and big storms. The fact that I do multiple interviews a winter implies that the storms themselves are not anomalous. If you actually count them, you end up with a decent number. You just need the dice to come up snake eyes — all the ingredients need to line up for it to be something impactful. And that’s what’s happening now.

What climate change does is change the underlying probabilities and distributions. But at the end of the day, the main thing that actually drives what’s going on with these storms is, can the atmosphere put the Lego pieces together for these impacts? Every cyclone that we get during the winter, if you go back and look at the historical record, there’s plenty of evidence for these types of storms.

On the California atom, Russian nuclear theft, and Taiwan’s geothermal hope

Current conditions: A blockbuster blizzard blanketed the Northeast in up to 2 feet of snow, trigger outages for nearly 500,000 households • Hot, dry Harmattan conditions are blowing into Nigeria out of the Sahara, leaving the capital, Abuja, and the largest city, Lagos, roasting in nearly 100 degrees Fahrenheit • Much of South Australia, the Northern Territory, and Victoria are bracing for severe thunderstorms and flooding.

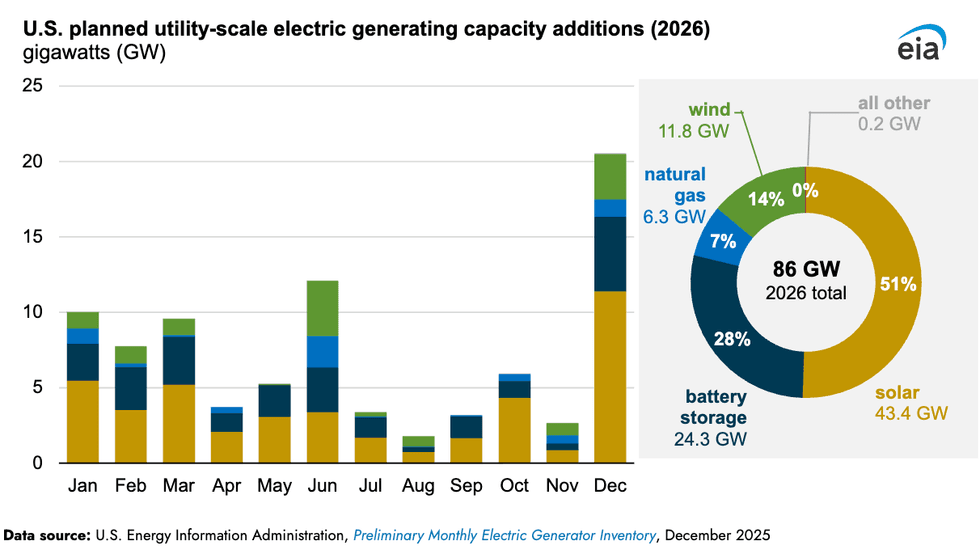

By the end of this year, U.S. developers are on pace to add 86 gigawatts of new utility-scale generating capacity to the American grid. Just 7% of that will come from natural gas. The other 93%? Solar, batteries, and wind, according to the latest inventory by the Energy Information Administration. Utility-scale solar projects alone will provide 51% of the new generating capacity, followed by batteries at 28%, and wind at 14%. Critics of renewables, such as Secretary of Energy Chris Wright, would point out that generating capacity does not equal generation, and that as has happened recently, gas, coal, and nuclear power may well end up pumping out a lot of the electricity this year. But rapid expansion of renewables and batteries comes largely despite the Trump administration’s efforts to curb the growth of what top officials dismiss as “unreliable” sources of power. Surging electricity demand from data centers has left gas turbines backordered; geothermal plants are still at an early stage; and new nuclear reactors are still years away. That makes solar and wind, already some of the cheapest sources to build, the only obvious options to bring new generation online as quickly as possible. In a sense, Trump may have helped nudge 2026’s boom into existence by phasing off federal tax credits for renewables this year, spurring a rush to get projects started and lock in the writeoffs.

That doesn’t mean the solar, battery, and wind sectors aren’t facing steep challenges. Just last week, Heatmap’s Jael Holzman rounded up four local fights on opposite coasts, including over a big solar farm in Oregon.

California could consider building anything from a large-scale Westinghouse AP1000 to a next-generation microreactor if a new bill to clarify the state’s ban on new nuclear power plants passes into law. On Friday, Assemblymember Lisa Calderon, a Democrat from Southern California, introduced AB2647 to modify the state moratorium put in place in 1976, three years before the Three Mile Island accident, to allow for construction of modern nuclear reactors. The legislation would exempt all reactor designs certified by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission after January 1, 2005. That clears the way for an AP1000, which was approved in 2006, and today is the only new design in commercial operation in the U.S., or any of the new small modular reactors and microreactors now racing to come to market. The bill is bringing together disparate factions in the California legislature. Progressive Assemblymember Alex Lee co-sponsored the legislation, while Senator Brian Jones, the highest ranking Republican in the state’s upper chamber, is backing a Senate version of the legislation.

Since Friday, I can report exclusively in this newsletter, the bill has two new supporters. Patrick Ahrens, a Silicon Valley-area Democrat, has signed on as a backer, and the Sheet Metal Workers union has said it would support the bill. “Pinching myself,” Ryan Pickering — a reactor developer and Berkeley-based activist who helped lead the successful campaign to cancel the closure of the state’s last plant, the Diablo Canyon nuclear station — responded when I texted him to ask about the bill. “California has an epic history in nuclear energy. We built 11 reactors across this state and once envisioned up to 14 gigawatts of nuclear electricity. This technology is part of our inheritance as Californians,” he said. “Assembly Bill 2647 gives California the opportunity to begin building nuclear energy again.”

If you have ever crossed the Queensboro Bridge from Manhattan’s 59th Street over to Long Island City in Queens, you have no doubt seen the Ravenswood Generating Station. The four candycane-colored smokestacks of New York City’s largest power plant, a more than 2-gigawatt facility equipped to burn both fuel oil and natural gas, rise on the lefthand side of the bridge, looming over the East River. Just a few years ago, its owner, LS Power, envisioned transforming the plant through a subsidiary called Rise Light and Power, which aimed to build a large-scale battery hub fed by new transmission lines connecting the facility to nearby offshore wind farms and onshore turbines upstate. Now, as Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo reported in a Friday scoop, the company is selling Ravenswood to the Texas energy giant NRG. It’s not yet clear what the sale means for the so-called Renewable Ravenswood plan, which Emily wrote was already “hanging by a thread.”

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Since the start of its invasion of Ukraine, Russia has maintained clear designs on the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant. Europe’s largest atomic generating station, located in an occupied province of eastern Ukraine, has been offline for the past four years. But, in a bid to shore up on the Kremlin’s desired war prizes as peace negotiations sputter, Russia’s nuclear regulator Rostekhnadzor has issued a 10-year operating license for Unit 2 of the plant. In its announcement, NucNet reported Friday, Rostekhnadzor said the move would open the door to building more Russian nuclear plants in the region. Rosatom, Moscow’s state-owned nuclear company, has submitted an application for an operating license for Unit 6, and aims to do the same for units 3, 4, and 5 by the end of this year.

The neighboring country most eager to contain Russia, meanwhile, took a big step toward building its first nuclear plant. The Supreme Administrative Court in Poland, whose debut facility is going with American technology, rejected an environmental complaint aimed at halting construction of AP1000 reactors at the site on the Baltic sea.

Earlier this month, I told you about Equinor’s plans to scale back its investments in carbon capture and sequestration, despite Norway’s world-leading progress on pumping captured CO2 back underground. Now the Norwegian energy giant is quitting on one of the European Union’s landmark projects to prove hydrogen fuel can be produced at scale using natural gas equipped with CCS. The company last week abandoned a gigawatt-sized blue hydrogen plant in the Netherlands as demand for the fuel stalls. Some may welcome the blue hydrogen recession. As Heatmap’s Katie Brigham wrote last year, a major blue hydrogen plant in Louisiana had been poised to add more emissions than it saved.

Things are looking sunnier in South America for green hydrogen, the carbon-free version of the fuel made from blasting freshwater with enough renewable electricity to separate out H from H2O. Colombia just completed a feasibility study on the country’s first industrial-scale green hydrogen project, set to generate 120,000 metric tons of green ammonia per year at a remarkably low price, according to Hydrogen Insight. At the opposite end of the continent, Uruguay’s 1.1-gigawatt green hydrogen-fueled methanol plant last week lined up a major offtaker that plans to buy the chemical to make lower-carbon gasoline. The purchaser? A fuel company based in a major artery of European trade, Germany’s Port of Hamburg.

Taiwan is in an energy crisis. The self-governing island, whose “silicon shield” against China is predicated on its capacity to manufacture enough energy-intensive semiconductors to be invaluable to the global economy, shut down its last nuclear reactor last year. By exiting atomic energy while struggling to build offshore wind turbines, the government in Taipei has rendered Taiwan almost entirely dependent on imported fuels. In an age when, as Russia has shown in Ukraine, blackouts are key weapons, the People’s Liberation Army need only make liquified natural gas dangerous to ship through the Taiwan Strait to cause blackouts. But geothermal power, development of which stalled out after the 1970s, offers a unique tool for Taiwan. Located on the Pacific Rim, the island has lots of hot rocks. Now it finally has a growing geothermal industry again, too. The CPC Corporation Taiwan said just before Lunar New Year started last week that it had just started generating power from the 5.4-megawatt Yilan Tuchang Geothermal plant. While small, it’s now the largest geothermal plant in Taiwan.

In this emergency episode, Rob unpacks the decision with international supply chain specialist Jonas Nahm.

The Supreme Court just struck down President Trump’s most ambitious tariff plan. What does that ruling mean for clean energy? For the data center boom? For America’s industrial policy?

On this emergency episode of Shift Key, Rob is joined by Jonas Nahm, a professor of economic and industrial policy at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, D.C. They discuss the ruling, the other authorities that Trump could now use to raise trade levies, and what (if anything) the change could mean for electric vehicles, solar panels, and more.

Shift Key is hosted by Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Here is an excerpt from their conversation:

Robinson Meyer: One thing I’m hearing in this list is that there’s five other tariff authorities he could use, and while some of them have restrictions on time or duration or tariff rate, there’s actually still a good amount of like untested tariff authority out there in the law. And if the president and his administration were quite devoted, they would be able to go out there and figure out the limits of 338, or figure out the limits of of 301?

Jonas Nahm: Yeah, I mean, I think one thing to also think about is, what is the purpose of these tariffs, right? And so I think the justifications from the administration have been varied and changed over time. But, you know, they’ve taken in a significant amount of revenue, some $30 billion a month from these tariffs. This was about four times as much as in the Biden administration. And so there is some money coming in from this. And so 122, the 10% immediately would bring back some of that revenue that is otherwise lost. One question is what’s going to happen to refunds from the IEEPA tariffs? Are they going to have to pay this back? It seems like that’s also kind of a court battle that needs to be fought out. And the Supreme Court didn’t weigh in on that. But, you know, the estimates show that if you brought the 122 in at 10%, you would actually recoup a lot of the money that you would otherwise lose and the effective tariff rate in the U.S. Would go back from 10% to about 15%, roughly to where it was before the Supreme Court ruled on it.

Meyer: Has the effect of tariffs from the Trump administration been larger or smaller than what you thought it would be? Not necessarily in the immediate aftermath of “liberation day” because he announced these giant tariffs and then kind of walked some of them back. But the tariff rate has gone up a lot in the past year. Has the effect of that on the economy been more or less than you expected?

Nahm: I think that the industrial policy justification that they have also used is a completely different bucket, right? So you can use this for revenue, and then you can just sort of tax different sectors at different times as long as the sum overall is what you want it to be. From an industrial policy perspective, all of this uncertainty is not very helpful because if you’re thinking about companies making major investment decisions and you have this IEEPA Supreme Court case sort of hanging over the situation for the past year, now we don’t know exactly what they’re going to replace it with, but you’re making a $10 billion decision to build a new manufacturing plant. You may want to sit that out until you know what exactly the environment is and also what the environment is for the components that you need to import, right? So a lot of U.S. imports actually go into domestic manufacturing. And so it’s not just the product that we’re trying to kind of compete with by making it domestically, but also the inputs that we need to make that product here that are being affected.

And so for those kinds of supply chain rewiring industrial policy decisions, you probably want a lot more certainty than we’ve had. And so the Supreme Court ruling against the IEEPA tariff justification is certainly more certainty in all of this. So we’ve now taken that off the list. But we are not clear what the new environment will look like and how long it’s going to stick around. And so from sort of an industrial policy perspective, that’s not really what you want. Ideally, what you would have is very predictable tariffs that give companies time to become competitive without the competition from abroad, and then also a very credible commitment to taking these tariffs away at some point so that the companies have an incentive to become competitive behind the tariff wall and then compete on their own. That’s sort of the ideal case. And we’re somewhat far from the ideal case. Given the uncertainty, given the lack of clarity on whether these things are going to stick around or not, or might be extended forever, and sort of the politics in the U.S. that make it much harder to take tariffs away than to impose them.

You can find a full transcript of the episode here.

Mentioned:

From Heatmap: Clean Energy Looks to (Mostly) Come Out Ahead After the Supreme Court’s Tariff Ruling

This episode of Shift Key is sponsored by ...

Accelerate your clean energy career with Yale’s online certificate programs. Explore the 10-month Financing and Deploying Clean Energy program or the 5-month Clean and Equitable Energy Development program. Use referral code HeatMap26 and get your application in by the priority deadline for $500 off tuition to one of Yale’s online certificate programs in clean energy. Learn more at cbey.yale.edu/online-learning-opportunities.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.