You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Everyone knows the story of Mrs. O’Leary’s cow, the one that allegedly knocked over a lantern in 1871 and burned down 2,100 acres of downtown Chicago. While the wildfires raging in Los Angeles County have already far exceeded that legendary bovine’s total attributed damage — at the time of this writing, on Thursday morning, five fires have burned more than 27,000 acres — the losses had centralized, at least initially, in the secluded neighborhoods and idyllic suburbs in the hills above the city.

On Wednesday, that started to change. Evacuation maps have since extended into the gridded streets of downtown Santa Monica and Pasadena, and a new fire has started north of Beverly Hills, moving quickly toward an internationally recognizable street: Hollywood Boulevard. The two biggest fires, Palisades and Eaton, remain 0% contained, and high winds have stymied firefighting efforts, all leading to an exceedingly grim question: Exactly how much of Los Angeles could burn. Could all of it?

“I hate to be doom and gloom, but if those winds kept up … it’s not unfathomable to think that the fires would continue to push into L.A. — into the city,” Riva Duncan, a former wildland firefighter and fire management specialist who now serves as the executive secretary of Grassroots Wildland Firefighters, an advocacy group, told me.

When a fire is burning in the chaparral of the hills, it’s one thing. But once a big fire catches in a neighborhood, it’s a different story. Houses, with their wood frames, gas lines, and cheap modern furniture, might as well be Duraflame. Embers from one burning house then leap to the next and alight in a clogged gutter or on shrubs planted too close to vinyl siding. “That’s what happened with the Great Chicago Fire. When the winds push fires like that, it’s pushing the embers from one house to the others,” Duncan said. “It’s a really horrible situation, but it’s not unfathomable to think about that [happening in L.A.] — but people need to be thinking about that, and I know the firefighters are thinking about that.”

Once flames engulf a block, it will “overpower” the capabilities of firefighters, Arnaud Trouvé, the chair of the Department of Fire Protection Engineering at the University of Maryland, told me in an email. If firefighters can’t gain a foothold, the fire will continue to spread “until a change in driving conditions,” such as the winds weakening to the point that a fire isn’t igniting new fuel or its fuel source running out entirely, when it reaches something like an expansive parking lot or the ocean.

This waiting game sometimes leads to the impression that firefighters are standing around, not doing anything. But “what I know they’re doing is they’re looking ahead to places where maybe there’s a park, or some kind of green space, or a shopping center with big parking lots — they’re looking for those places where they could make a stand,” Duncan told me. If an entire city block is already on fire, “they’re not going to waste precious water there.”

Urban firefighting is a different beast than wildland firefighting, but Duncan noted that Forest Service, CALFIRE, and L.A. County firefighters are used to complex mixed environments. “This is their backyard, and they know how to fight fire there.”

“I can guarantee you, many of them haven’t slept 48 hours,” she went on. “They’re grabbing food where they can; they’re taking 15-minute naps. They’re in this really horrible smoke — there are toxins that come off burning vehicles and burning homes, and wildland firefighters don’t wear breathing apparatus to protect the airways. I know they all have horrible headaches right now and are puking. I remember those days.”

If there’s a sliver of good news, it’s that the biggest fire, Palisades, can’t burn any further to the west, the direction the wind is blowing — there lies the ocean — meaning its spread south into Santa Monica toward Venice and Culver City or Beverly Hills is slower than it would be if the winds shifted. The westward-moving Santa Ana winds, however, could conceivably fan the Eaton fire deeper into eastern Los Angeles if conditions don’t let up soon. “In many open fires, the most important factor is the wind,” Trouvé explained, “and the fire will continue spreading until the wind speed becomes moderate-to-low.”

Though the wind died down a bit on Wednesday night, conditions are expected to deteriorate again Thursday evening, and the red flag warning won’t expire until Friday. And “there are additional winds coming next week,” Kristen Allison, a fire management specialist with the Southern California Geographic Area Coordination Center, told me Wednesday. “It’s going to be a long duration — and we’re not seeing any rain anytime soon.”

Editor’s note: Firefighting crews made “big gains” overnight against the Sunset fire, which threatened famous landmarks like the TLC Chinese Theater and the Dolby Theatre, which will host the Academy Awards in March. Most of the mandatory evacuation notices remaining in Hollywood on Thursday morning were out of precaution, the Los Angeles Times reported. Meanwhile, the Palisades and Eaton fires have burned a combined 27,834 acres, destroyed 2,000 structures, killed at least five people, and remain unchecked as the winds pick up again. This piece was last updated on January 9 at 10:30 a.m. ET.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Europeans have been “snow farming” for ages. Now the U.S. is finally starting to catch on.

February 2015 was the snowiest month in Boston’s history. Over 28 days, the city received a debilitating 64.8 inches of snow; plows ran around the clock, eventually covering a distance equivalent to “almost 12 trips around the Equator.” Much of that plowed snow ended up in the city’s Seaport District, piled into a massive 75-foot-tall mountain that didn’t melt until July.

The Seaport District slush pile was one of 11 such “snow farms” established around Boston that winter, a cutesy term for a place that is essentially a dumpsite for snow plows. But though Bostonians reviled the pile — “Our nightmare is finally over!” the Massachusetts governor tweeted once it melted, an event that occasioned multiple headlines — the science behind snow farming might be the key to the continuation of the Winter Olympics in a warming world.

The number of cities capable of hosting the Winter Games is shrinking due to climate change. Of 93 currently viable host locations, only 52 will still have reliable winter conditions by the 2050s, researchers found back in 2024. In fact, over the 70 years since Cortina d’Ampezzo first hosted the Olympic Games in 1956, February temperatures in the Dolomites have warmed by 6.4 degrees Fahrenheit, according to Climate Central, a nonprofit climate research and communications group. Italian organizers are expected to produce more than 3 million cubic yards of artificial snow this year to make up for Mother Nature’s shortfall.

But just a few miles down the road from Bormio — the Olympic venue for the men’s Alpine skiing events as well as the debut of ski mountaineering next week — is the satellite venue of Santa Caterina di Valfurva, which hasn’t struggled nearly as much this year when it comes to usable snow. That’s because it is one of several European ski areas that have begun using snow farming to their advantage.

Like Ruka in Finland and Saas-Fee in Switzerland, Santa Caterina plows its snow each spring into what is essentially a more intentional version of the Great Boston Snow Pile. Using patented tarps and siding created by a Finnish company called Snow Secure, the facilities cover the snow … and then wait. As spring turns to summer, the pile shrinks, not because it’s melting but because it’s becoming denser, reducing the air between the individual snowflakes. In combination with the pile’s reduced surface area, this makes the snow cold and insulated enough that not even a sunny day will cause significant melt-off. (Neil DeGrasse Tyson once likened the phenomenon to trying to cook an entire potato with a lighter; successfully raising the inner temperature of a dense snowball, much less a gigantic snow pile, requires more heat.)

Shockingly little snow melts during storage. Snow Secure reports a melt rate of 8% to 20% on piles that can be 50,000 cubic meters in size, or the equivalent of about 20 Olympic swimming pools. When autumn eventually returns, ski areas can uncover their piles of farmed snow and spread it across a desired slope or trail using snowcats, specialized groomers that break up and evenly distribute the surface. For Santa Caterina, the goal was to store enough to make a nearly 2-mile-long cross-country trail — no need to wait for the first significant snowfall of the season, which creeps later and later every year.

“In many places, November used to be more like a winter month,” Antti Lauslahti, the CEO of Snow Secure, told me. “Now it’s more like a late-autumn month; it’s quite warm and unpredictable. Having that extra few weeks is significant. When you cannot open by Thanksgiving or Christmas, you can lose 20% to 30% of the annual turnover.”

Though the concept of snow farming is not new — Lauslahti told me the idea stems from the Finnish tradition of storing snow over the summer beneath wood chips, once a cheap byproduct of the local logging industry — the company's polystyrene mat technology, which helps to reduce summer melt, is. Now that the technique is patented, Snow Secure has begun expanding into North America with a small team. The venture could prove lucrative: Researchers expect that by the end of the century, as many as 80% of the downhill ski areas in the U.S. will be forced to wait until after Christmas to open, potentially resulting in economic losses of up to $2 billion.

While there have been a few early adopters of snow farming in Wisconsin, Utah, and Idaho, the number of ski areas in the United States using the technique remains surprisingly low, especially given its many other upsides. In the States, the most common snow management system is the creation of artificial snow, which is typically water- and energy-intensive. Snow farming not only avoids those costs — which can also have large environmental tolls, particularly in the water-strapped West — but the super-dense snow farming produces is “really ideal” for something like the Race Centre at Canada’s Sun Peaks Resort, where top athletes train. Downhill racers “want that packed, harder, faster snow,” Christina Antoniak, the area’s director of brand and communications, told me of the success of the inaugural season of snow farming at Sun Peaks. “That’s exactly what stored snow produced for that facility.”

The returns are greatest for small ski areas, which are also the most vulnerable to climate change. While the technology is an investment — Antoniak ballparked that Sun Peaks spent around $185,000 on Snow Secure’s siding — the money goes further at a smaller park. At somewhere like Park City Mountain in Utah, stored snow would cover only a small portion of the area’s 140 miles of skiable routes. But it can make a major difference for an area down the road like the Soldier Hollow Nordic Center, which has a more modest 20 miles of cross-country trails.

In fact, the 2025-2026 winter season will be the Nordic Center’s first using Snow Secure’s technology. Luke Bodensteiner, the area’s general manager and chief of sport, told me that alpine ski areas are “all very curious to see how our project goes. There is a lot of attention on what we do, and if it works out satisfactorily, we might see them move into it.”

Ensuring a reliable start to the ski season is no small thing for a local economy; jobs and travel plans rely on an area being open when it says it will be. But for the Soldier Hollow Nordic Center, the stakes are even higher: The area is one of the planned host venues of the 2034 Salt Lake City Winter Games. “Based on historical weather patterns, our goal is to be able to make all the snow that we need for the entire Olympic trail system in two weeks,” Bodensteiner said, adding, “We envision having four or five of these snow piles around the venue in the summer before the Olympic Games, just to guarantee — in a worst case scenario — that we’ve got snow on the venue.”

Antoniak, at Canada’s Sun Peaks, also told me that their area has been a bit of a “guinea pig” when it comes to snow farming. “A lot of ski areas have had their eyes on Sun Peaks and how [snow farming is] working here,” she told me. “And we’re happy to have those conversations with them, because this is something that gives the entire industry some more resiliency.”

Of course, the physics behind snow farming has a downside, too. The same science saving winter sports is also why that giant, dirty pile of plowed snow outside your building isn’t going anywhere anytime soon.

Current conditions: A train of three storms is set to pummel Southern California with flooding rain and up to 9 inches mountain snow • Cyclone Gezani just killed at least four people in Mozambique after leaving close to 60 dead in Madagascar • Temperatures in the southern Indian state of Kerala are on track to eclipse 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

What a difference two years makes. In April 2024, New York announced plans to open a fifth offshore wind solicitation, this time with a faster timeline and $200 million from the state to support the establishment of a turbine supply chain. Seven months later, at least four developers, including Germany’s RWE and the Danish wind giant Orsted, submitted bids. But as the Trump administration launched a war against offshore wind, developers withdrew their bids. On Friday, Albany formally canceled the auction. In a statement, the state government said the reversal was due to “federal actions disrupting the offshore wind market and instilling significant uncertainty into offshore wind project development.” That doesn’t mean offshore wind is kaput. As I wrote last week, Orsted’s projects are back on track after its most recent court victory against the White House’s stop-work orders. Equinor's Empire Wind, as Heatmap’s Jael Holzman wrote last month, is cruising to completion. If numbers developers shared with Canary Media are to be believed, the few offshore wind turbines already spinning on the East Coast actually churned out power more than half the time during the recent cold snap, reaching capacity factors typically associated with natural gas plants. That would be a big success. But that success may need the political winds to shift before it can be translated into more projects.

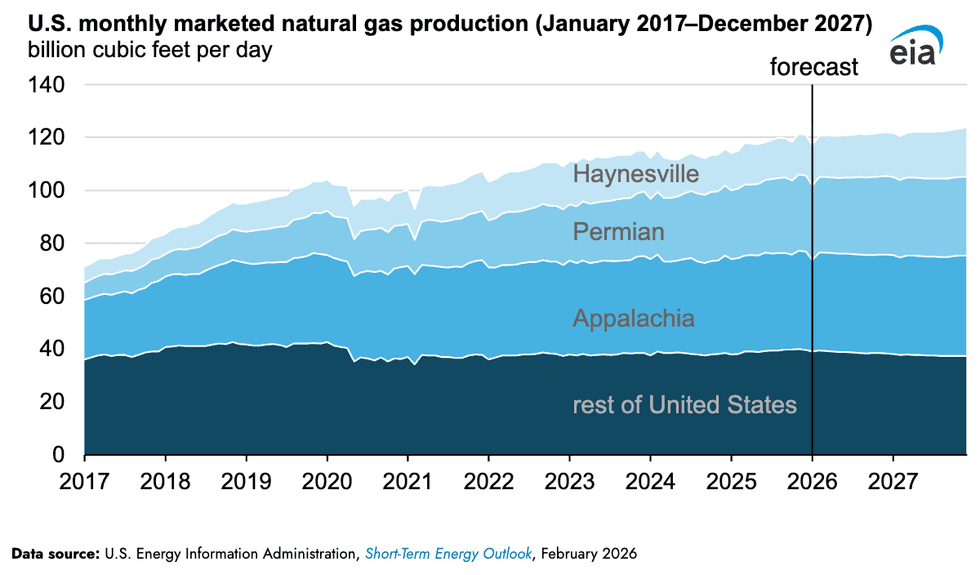

President Donald Trump’s “drill, baby, drill” isn’t moving American oil extractors, whose output is set to contract this year amid a global glut keeping prices low. But production of natural gas is set to hit a record high in 2026, and continue upward next year. The Energy Information Administration’s latest short-term energy outlook expects natural gas production to surge 2% this year to 120.8 billion cubic feet per day, from 118 billion in 2025 — then surge again next year to 122.3 billion cubic feet. Roughly 69% of the increased output is set to come from Appalachia, Louisiana’s Haynesville area, and the Texas Permian regions. Still, a lot of that gas is flowing to liquified natural gas exports, which Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin explained could raise prices.

The U.S. nuclear industry has yet to prove that microreactors can pencil out without the economies of scale that a big traditional reactor achieves. But two of the leading contenders in the race to commercialize the technology just crossed major milestones. On Friday, Amazon-backed X-energy received a license from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to begin commercial production of reactor fuel high-assay low-enriched uranium, the rare but potent material that’s enriched up to four times higher than traditional reactor fuel. Due to its higher enrichment levels, HALEU, pronounced HAY-loo, requires facilities rated to the NRC’s Category II levels. While the U.S. has Category I facilities that handle low-enriched uranium and Category III facilities that manage the high-grade stuff made for the military, the country has not had a Category II site in operation. Once completed, the X-energy facility will be the first, in addition to being the first new commercial fuel producer licensed by the NRC in more than half a century.

On Sunday, the U.S. government airlifted a reactor for the first time. The Department of Defense transported one of Valar Atomics’ 5-megawatt microreactors via a C-17 from March Air Reserve Base in California to Hill Air Force Base in Utah. From there, the California-based startup’s reactor will go to the Utah Rafael Energy Lab in Orangeville, Utah, for testing. In a series of posts on X, Isaiah Taylor, Valar’s founder, called the event “a groundbreaking unlock for the American warfighters.” His company’s reactor, he said, “can power 5,000 homes or sustain a brigade-scale” forward operating base.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

After years of attempting to sort out new allocations from the dwindling Colorado River, negotiators from states and the federal government disbanded Friday without a plan for supplying the 40 million people who depend on its waters. Upper-basin states Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico have so far resisted cutting water usage when lower-basin states California, Arizona, and Nevada are, as The Guardian put it, “responsible for creating the deficit” between supply and demand. But the lower-basin states said they had already agreed to substantial cuts and wanted the northern states to share in the burden. The disagreement has created an impasse for months; negotiators blew through deadlines in November and January to come up with a solution. Calling for “unprecedented cuts” that he himself described as “unbelievably harsh,” Brad Udall, senior water and climate research scientist at Colorado State University’s Colorado Water Center, said: “Mother Nature is not going to bail us out.”

In a statement Friday, Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum described “negotiations efforts” as “productive” and said his agency would step in to provide guidelines to the states by October.

Europe’s “regulatory rigidity risks undermining the momentum of the hydrogen economy. That, at least, is the assessment of French President Emmanuel Macron, whose government has pumped tens of billions of euros into the clean-burning fuel and promoted the concept of “pink hydrogen” made with nuclear electricity as the solution that will make energy technology take off. Speaking at what Hydrogen Insight called “a high-level gathering of CEOs and European political leaders,” Macron, who is term-limited in next year’s presidential election, said European rules are “a crazy thing.” Green hydrogen, the version of the fuel made with renewable electricity, remains dogged by high prices that the chief executive of the Spanish oil company Repsol said recently will only come down once electricity rates decrease. The Dutch government, meanwhile, just announced plans to pump 8 billion euros, roughly $9.4 billion, into green hydrogen.

Kazakhstan is bringing back its tigers. The vast Central Asian nation’s tiger reintroduction program achieved record results in reforesting an area across the Ili River Delta and Southern Balkhash region, planting more than 37,000 seedlings and cuttings on an area spanning nearly 24 acres. The government planted roughly 30,000 narrow-leaf oleaster seedlings, 5,000 willow cuttings, and about 2,000 turanga trees, once called a “relic” of the Kazakh desert. Once the forests come back, the government plans to eventually reintroduce tigers, which died out in the 1950s.

In this special episode, Rob goes over the repeal of the “endangerment finding” for greenhouse gases with Harvard Law School’s Jody Freeman.

President Trump has opened a new and aggressive war on the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to limit climate pollution. Last week, the EPA formally repealed its scientific determination that greenhouse gases endanger human health and the environment.

On this week’s episode of Shift Key, we find out what happens next.

Rob is joined by Jody Freeman, the director of the Environmental and Energy Law Program at Harvard Law School, to discuss the Trump administration’s war on the endangerment finding. They chat about how the Trump administration has already changed its argument since last summer, whether the Supreme Court will buy what it’s selling, and what it all means for the future of climate law.

They also talk about whether the Clean Air Act has ever been an effective tool to fight greenhouse gas pollution — and whether the repeal could bring any upside for states and cities.

Shift Key is hosted by Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Here is an excerpt from our conversation:

Jody Freeman: The scientific community, you know, filed comments on this proposal and just knocked all of the claims in the report out of the box, and made clear how much evidence not only there was in 2009, for the endangerment finding, but much more now. And they made this very clear. And the National Academies of Science report was excellent on this. So they did their job. They reflected the state of the science and EPA has dropped any frontal attack on the science underlying the endangerment finding.

Now, it’s funny. My reaction to that is like twofold. One, like, yay science, right? Go science. But two is, okay, well, now the proposal seems a little less crazy, right? Or the rule seems a little less crazy. But I still think they had to fight back on this sort of abuse of the scientific record. And now it is the statutory arguments based on the meaning of these words in the law. And they think that they can get the Supreme Court to bite on their interpretation.

And they’re throwing all of these recent decisions that the Supreme Court made into the argument to say, look what you’ve done here. Look what you’ve done there. You’ve said that agencies need explicit authority to do big things. Well, this is a really big thing. And they characterize regulating transportation sector emissions as forcing a transition to EVs. And so to characterize it as this transition unheralded, you know, and they need explicit authority, they’re trying to get the court to bite. And, you know, they might succeed, but I still think some of these arguments are a real stretch.

Robinson Meyer: One thing I would call out about this is that while they’ve taken the climate denialism out of the legal argument, they cannot actually take it out of the political argument. And even yesterday, as the president was announcing this action — which, I would add, they described strictly in deregulatory terms. In fact, they seemed eager to describe it not as an environmental action, not as something that had anything to do with air and water, not even as a place where they were. They mentioned the Green New Scam, quote-unquote, a few times. But mostly this was about, oh, this is the biggest deregulatory action in American history.

It’s all about deregulation, not about like something about the environment, you know, or something about like we’re pushing back on those radicals. It was ideological in tone. But even in this case, the president couldn’t help himself but describe climate change as, I think the term he used is a giant scam. You know, like even though they’ve taken, surgically removed the climate denialism from the legal argument, it has remained in the carapace that surrounds the actual ...

Freeman: And I understand what they say publicly is, you know, deeply ideological sounding and all about climate is a hoax and all that stuff. But I think we make a mistake … You know, we all get upset about the extent to which the administration will not admit physics is a reality, you know, and science is real and so on. But, you know, we shouldn’t get distracted into jumping up and down about that. We should worry about their legal arguments here and take them seriously.

You can find a full transcript of the episode here.

Mentioned:

From Heatmap: The 3 Arguments Trump Used to Gut Greenhouse Gas Regulations

Previously on Shift Key: Trump’s Move to Kill the Clean Air Act’s Climate Authority Forever

Rob on the Loper Bright case and other Supreme Court attacks on the EPAThis episode of Shift Key is sponsored by ...

This episode of Shift Key is sponsored by ...

Accelerate your clean energy career with Yale’s online certificate programs. Explore the 10-month Financing and Deploying Clean Energy program or the 5-month Clean and Equitable Energy Development program. Use referral code HeatMap26 and get your application in by the priority deadline for $500 off tuition to one of Yale’s online certificate programs in clean energy. Learn more at cbey.yale.edu/online-learning-opportunities.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.