You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

It’s the first project to turn steel-related emissions into products. But can it scale?

Last week, the Department of Energy announced $6 billion in awards to help clean up some of the most greenhouse gas-intensive industries in the U.S., including $1.5 billion to transform iron and steel manufacturing. U.S. Steel, one of the biggest American steelmakers, was not among the recipients.

On Wednesday, U.S. Steel made an announcement of its own: It is signing a 20-year agreement with CarbonFree, a Texas-based company, to capture carbon dioxide from Gary Works, the largest integrated steel mill in the country, and turn it into a marketable product. The $150 million project is the first to capture and utilize carbon from an American steel plant at a commercial scale.

Gary Works releases an ungodly amount of carbon into the air each year — more than the entire state of Vermont. CarbonFree will use its technology, known as SkyCycle, to collect 50,000 tons of CO2 from the plant per year and transform it into high grade calcium carbonate, a valuable ingredient for the food, pharmaceuticals, paint, and plastics industries.

Something certainly has to change if U.S. Steel is going to make good on its pledge of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050, let alone stay competitive in a market that’s expected to increasingly look for greener products. It’s unclear, however, whom the company is going to convince with this project, which will capture less than 1% of the plant’s annual emissions.

“It’s deeply unserious, I think, is the words that come to mind,” Hilary Lewis, the steel director at Industrious Labs, a nonprofit that advocates for decarbonizing heavy industry, told me. The effort is especially embarrassing, she said, given that two of the company’s competitors, SSAB and Cleveland Cliffs, were awarded $500 million each by the DOE for far more transformative green steel projects. “This announcement is emblematic of how U.S. Steel is a laggard.”

U.S. Steel declined to make any of its executives available to interview for this story. In response to my request for comment, the company provided a statement that said this was a first of its kind opportunity to “significantly reduce” emissions at Gary Works, and that it was “the first step in exploring the scalability of this technology” to support the company’s goals.

CarbonFree executives, too, asserted that the Gary Works project is a stepping stone to something bigger. But outside experts I spoke with were skeptical that it would be able to scale enough to make a meaningful difference in the plant’s — or the industry’s — emissions.

The steel industry contributes about 8% of global energy-related emissions. Though the U.S. is not one of the worst offenders (we actually make some of the cleanest steel in the world) U.S. steelmakers still have a long, expensive journey ahead to decarbonize.

That’s because there are eight steel plants in the U.S. that still use blast furnaces, a dirty, coal-intensive production method. Gary Works is one of them. Though these plants only represent about 30% of the country’s steel production, they are responsible for nearly 70% of the sector’s emissions, according to the Department of Energy.

The advantage of the SkyCycle project is that it doesn’t require U.S. Steel to do very much. “We build, own, and operate the [carbon capture equipment], and we’re able to get a return based on the chemicals we sell,” Martin Keighley, the CEO of CarbonFree, told me. “So it’s a much more attractive proposition for, in this case, U.S. Steel, because they don't have to invest large amounts of money into the plant.” More attractive than at least one alternative, that is, which is to capture the carbon and sequester it underground.

It’s a compelling argument. Carbon capture and storage adds big costs — to install the equipment, transport the CO2, and pump it into the bedrock — with no financial benefit to manufacturers. While the federal government does encourage carbon capture by offering an $85 federal tax credit for every ton of CO2 captured and stored, no law compels steel companies to do so. In many cases, the subsidy may not be not enough to get investors on board for a project, especially since tax credits can come and go depending on the whims of Congress.

But if you find someone else who can take your carbon and make money off of it, then what have you got to lose? Keighley said CarbonFree will be able to earn a slightly smaller federal tax credit — $60 — for every ton of carbon it turns into calcium carbonate, but that the company’s business model doesn’t depend on that.

“You know, we all look at 2050 and net zero, but it doesn't stop there. To be net zero, we’re still emitting CO2, so we still have to capture it,” he said, referring to the idea that the “net” in net zero implies there will continue to be emissions that must be neutralized. “We're going to be capturing forever. So, therefore, we need sustainable business models that aren’t reliant on government sources.”

One advantage of SkyCycle over other carbon capture technologies is that it works with raw, dirty flue gas, which might have all kinds of other gases and chemicals mixed in with the CO2. The gas is channeled through a series of chemical reactions and eventually reacts with calcium, a mineral that’s notoriously thirsty for CO2, to create calcium carbonate. Once it binds with calcium, the CO2 is essentially locked up permanently. It would take either very high heat or a very strong acid to remove it.

Keighley said the high grade calcium carbonate on the market today has much greater emissions associated with its production than CarbonFree’s process, and is about the same price. That creates a “multiplier effect,” he told me. Not only is the company reducing emissions from the Gary Works plant, it’s also reducing emissions associated with the products that incorporate the cleaner calcium carbonate. On top of that, the company is sourcing its calcium from steel slag, a waste product from the steelmaking process that nobody has really figured out what to do with. (This is different from blast furnace slag, which is valuable for decarbonizing the cement industry as a replacement for carbon-intensive “clinker.”)

So far, so good. But the issue, according to Rebecca Dell, a former Department of Energy analyst and senior director of industry at the ClimateWorks Foundation, is that the market for high grade calcium carbonate is tiny. “You’re gonna saturate these high end markets way before you get anywhere close to absorbing the full 8 or 9 million tons a year of CO2 that just the Gary Works is emitting,” she told me.

When I raised this with Keighley, he acknowledged that the market was limited. But he said the market for calcium carbonate in general, not just the high purity stuff, is much bigger, and that the company could move into other segments later. CarbonFree is already working on its next system, which will be capable of capturing 250,000 tons of CO2 per year. Calcium carbonate is essentially limestone, which is an abundant and cheap material, so it might be hard to compete in lower-grade markets without bringing down production costs. But Keighley mentioned another plan. “The beauty is, if and when you run out of market altogether, you store it,” he told me. In other words, the company could just stash the calcium carbonate on the grounds of the Gary Works plant. That assumes, however, that they’ve brought down their costs enough to make a profit off the federal tax credit for carbon storage — and that assumes the tax credit still exists.

Lewis, of Industrious Labs, raised a different issue. “If you’re choosing to invest in carbon capture, you're locking in that reliance on coal for another 15, 20 years,” she told me. Carbon capture doesn’t address the other health-harming pollutants these steel mills rain over their surrounding community, including nitrous oxides, sulfur dioxide, and soot. She also noted that the biggest consumer of the types of steel produced by blast furnaces, the auto industry, has ambitious climate targets. While automakers have yet to make truly market-transforming commitments to buy cleaner steel, if and when they do, Gary Works could be left unprepared, threatening the job security of its more than 4,000 workers.

U.S. Steel’s plan is a stark contrast to one of the projects awarded funding by the DOE last week, Lewis said. Cleveland Cliffs, which owns five of the remaining seven blast furnace steel mills, will get $500 million to replace one of its blast furnaces at a mill in Ohio with what’s called a “direct reduced iron” plant. Direct reduction is more efficient, cleaner, and cheaper than a blast furnace; the company said it would save $150 per ton of steel produced by making the switch. Though some direct reduction plants rely on natural gas, and therefore aren’t exactly carbon-free, the process can also be done with green hydrogen. That’s what a second project announced last week, led by the Swedish steelmaker SSAB, will be using at a new plant in Mississippi.

In my interview with Keighley, I asked what he thought about the criticism that this project would keep Gary Works hooked on coal for another 20 years, and that advocates wanted to see the plant transition to direct reduction. He responded by raising questions about green hydrogen. Producing green hydrogen requires lots of renewable energy, he said. Is that the best use of that renewable energy, or could you “get more decarbonization for your buck” by using it for something else?

Later, in an email, Keighley also pointed to SkyCycle’s readiness for deployment compared to the long development timelines for other solutions. Construction is expected to start as early as summer 2024, with operations beginning in 2026. He also emphasized that CarbonFree would be able to “easily” increase the size of the plant. “There’s so many different options and everyone’s trying to second guess everybody else. Just get on with doing something, you know?”

But Chris Bataille, a research fellow at the Columbia University Center on Global Energy Policy who focuses on pathways to net-zero for heavy industry, told me the tiny scope of this project is indicative of a larger issue. “These marginal changes are attractive to people who are just used to running a blast furnace their whole careers,” he said. “You can keep the rest of your plant, but that piece of equipment needs to change.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Heron Power and DG Matrix each score big funding rounds, plus news for heat pumps and sustainable fashion.

While industries with major administrative tailwinds such as nuclear and geothermal have been hogging the funding headlines lately, this week brings some variety with news featuring the unassuming but ever-powerful transformer. Two solid-state transformer startups just announced back-to-back funding rounds, promising to bring greater efficiency and smarter services to the grid and data centers alike. Throw in capital supporting heat pump adoption and a new fund for sustainable fashion, and it looks like a week for celebrating some of the quieter climate tech solutions.

Transformers are the silent workhorses of the energy transition. These often-underappreciated devices step up voltage for long-distance electricity transmission and step it back down so that it can be safely delivered to homes and businesses. As electrification accelerates and data centers race to come online, demand for transformers has surged — more than doubling since 2019 — creating a supply crunch in the U.S. that’s slowing the deployment of clean energy projects.

Against this backdrop, startup Heron Power just raised a $140 million Series B round co-led by Andreessen Horowitz and Breakthrough Energy Ventures to build next-generation solid state transformers. The company said its tech will be able to replace or consolidate much of today’s bulky transformer infrastructure, enabling electricity to move more efficiently between low-voltage technologies like solar, batteries, and data centers and medium-voltage grids. Heron’s transformers also promise greater control than conventional equipment, using power electronics and software to actively manage electricity flows, whereas traditional transformers are largely passive devices designed to change voltage.

This new funding will allow Heron to build a U.S.manufacturing facility designed to produce around 40 gigawatts of transformer equipment annually; it expects to begin production there next year. This latest raise follows quickly on the heels of its $38 million Series A round last May, reflecting hunger among customers for more efficient and quicker to deploy grid infrastructure solutions. Early announced customers include the clean energy developer Intersect Power and the data center developer Crusoe.

It’s a good time to be a transformer startup. DG Matrix, which also develops solid-state transformers, closed a $60 million Series A this week, led by Engine Ventures. The company plans to use the funding to scale its manufacturing and supply chain as it looks to supply data centers with its power-conversion systems.

Solid-state transformers — which use semiconductors to convert and control electricity — have been in the research and development phase for decades. Now they’re finally reaching the stage of technical maturity needed for commercial deployment, driving a surge in activity across the industry. DG Matrix’s emphasis is on creating flexible power conversion solutions, marketing its product as the world’s first “multi-port” solid-state transformer capable of managing and balancing electricity from multiple different sources at once.

“This Series A marks our transition from breakthrough technology to scaled infrastructure deployment,” Haroon Inam, DG Matrix’s CEO, said in a statement. “We are working with hyperscalers, energy companies, and industrial customers across North America and globally, with multiple gigawatt-class datacenters in the pipeline.” According to TechCrunch, data centers make up roughly 90% of DG Matrix’s current customer base, as its transformers can significantly reduce the space data centers require for power conversion.

Zero Homes, a digital platform and marketplace that helps homeowners manage the heat pump installation process, just announced a $16.8 million Series A round led by climate tech investor Prelude Ventures. The company’s free smartphone app lets customers create a “digital twin” of their home — a virtual model that mirrors the real-world version, built from photos, videos, and utility data. This allows homeowners to get quotes, purchase, and plan for their HVAC upgrade without the need for a traditional in-person inspection. The company says this will cut overall project costs by 20% on average.

Zero works with a network of vetted independent installers across the U.S., with active projects in California, Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, and Illinois. As the startup plans for national expansion, it’s already gained traction with some local governments, partnering with Chicago on its Green Homes initiative and netting $745,000 from Colorado’s Office of Economic Development to grow its operations in Denver.

Climactic, an early-stage climate tech VC, launched a new hybrid fund called Material Scale, aimed at helping sustainable materials and apparel startups navigate the so-called “valley of death” — the gap between early-stage funding and the later-stage capital needed to commercialize. As Climactic’s cofounder Josh Fesler explained on LinkedIn, the fund is designed to cover the extra costs involved with sustainable production, bridging the gap between the market price of conventional materials and the higher price of sustainable materials.

Structured as a “hybrid debt-equity platform,” the fund allows Climactic’s investors to either take a traditional equity stake in materials startups or provide them with capital in the form of loans. TechCrunch reports that the fund’s initial investments will come from an $11 million special purpose vehicle, a separate entity created to fund a small set of initial investments that sits outside Material Scale’s main investing pool.

The fashion industry accounts for roughly 10% of global emissions. “These days there are many alt materials startups that have moved through science and structural risk, have venture funding, credible supply chains and most importantly can achieve market price and positive gross margins just with scale,” Fesler wrote in his LinkedIn post. “They just need the capital to grow into their rightful commercial place.”

Clean energy stocks were up after the court ruled that the president lacked legal authority to impose the trade barriers.

The Supreme Court struck down several of Donald Trump’s tariffs — the “fentanyl” tariffs on Canada, Mexico, and China and the worldwide “reciprocal” tariffs ostensibly designed to cure the trade deficit — on Friday morning, ruling that they are illegal under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act.

The actual details of refunding tariffs will have to be addressed by lower courts. Meanwhile, the White House has previewed plans to quickly reimpose tariffs under other, better-established authorities.

The tariffs have weighed heavily on clean energy manufacturers, with several companies’ share prices falling dramatically in the wake of the initial announcements in April and tariff discussion dominating subsequent earnings calls. Now there’s been a sigh of relief, although many analysts expected the Court to be extremely skeptical of the Trump administration’s legal arguments for the tariffs.

The iShares Global Clean Energy ETF was up almost 1%, and shares in the solar manufacturer First Solar and the inverter company Enphase were up over 5% and 3%, respectively.

First Solar initially seemed like a winner of the trade barriers, however the company said during its first quarter earnings call last year that the high tariff rate and uncertainty about future policy negatively affected investments it had made in Asia for the U.S. market. Enphase, the inverter and battery company, reported that its gross margins included five percentage points of negative impact from reciprocal tariffs.

Trump unveiled the reciprocal tariffs on April 2, a.k.a. “liberation day,” and they have dominated decisionmaking and investor sentiment for clean energy companies. Despite extensive efforts to build an American supply chain, many U.S. clean energy companies — especially if they deal with batteries or solar — are still often dependent on imports, especially from Asia and specifically China.

In an April earnings call, Tesla’s chief financial officer said that the impact of tariffs on the company’s energy business would be “outsized.” The turbine manufacturer GE Vernova predicted hundreds of millions of dollars of new costs.

Companies scrambled and accelerated their efforts to source products and supplies from the United States, or at least anywhere other than China.

Even though the tariffs were quickly dialed back following a brutal market reaction, costs that were still being felt through the end of last year. Tesla said during its January earnings call that it expected margins to shrink in its energy business due to “policy uncertainty” and the “cost of tariffs.”

Current conditions: More than a foot of snow is blanketing the California mountains • With thousands already displaced by flooding, Papua New Guinea is facing more days of thunderstorms ahead • It’s snowing in Ulaanbaatar today, and temperatures in the Mongolian capital will plunge from 31 degrees Fahrenheit to as low as 2 degrees by Sunday.

We all know the truisms of market logic 101. Precious metals surge when political volatility threatens economic instability. Gun stocks pop when a mass shooting stirs calls for firearm restrictions. And — as anyone who’s been paying attention to the world over the past year knows — oil prices spike when war with Iran looks imminent. Sure enough, the price of crude hit a six-month high Wednesday before inching upward still on Thursday after President Donald Trump publicly gave Tehran 10 to 15 days to agree to a peace deal or face “bad things.” Despite the largest U.S. troop buildup in the Middle East since 2003, the American military action won’t feature a ground invasion, said Gregory Brew, the Eurasia Group analyst who tracks Iran and energy issues. “It will be air strikes, possibly commando raids,” he wrote Thursday in a series of posts on X. Comparisons to Iraq “miss the mark,” he said, because whatever Trump does will likely wrap up in days. The bigger issue is that the conflict likely won’t resolve any of the issues that make Iran such a flashpoint. “There will be no deal, the regime will still be there, the missile and nuclear programs will remain and will be slowly rebuilt,” Brew wrote. “In six months, we could be back in the same situation.”

California, Colorado, and Washington led 10 other states in suing the Trump administration this week over the Department of Energy’s termination of billions in federal funding for clean energy and infrastructure projects. In a lawsuit filed in federal court in San Francisco, the states accuse the agency of using a “nebulous and opaque” review process to justify slashing billions in funding that was already awarded. “These aren’t optional programs — these are investments approved by bipartisan majorities in Congress,” California Attorney General Rob Bonta said at a press conference announcing the lawsuit, according to Courthouse News Service. “The president doesn’t get to cancel them simply because he disagrees with them. California won’t allow President Trump and his administration to play politics with our economy, our energy grid and our jobs.”

Get Heatmap AM directly in your inbox every morning:

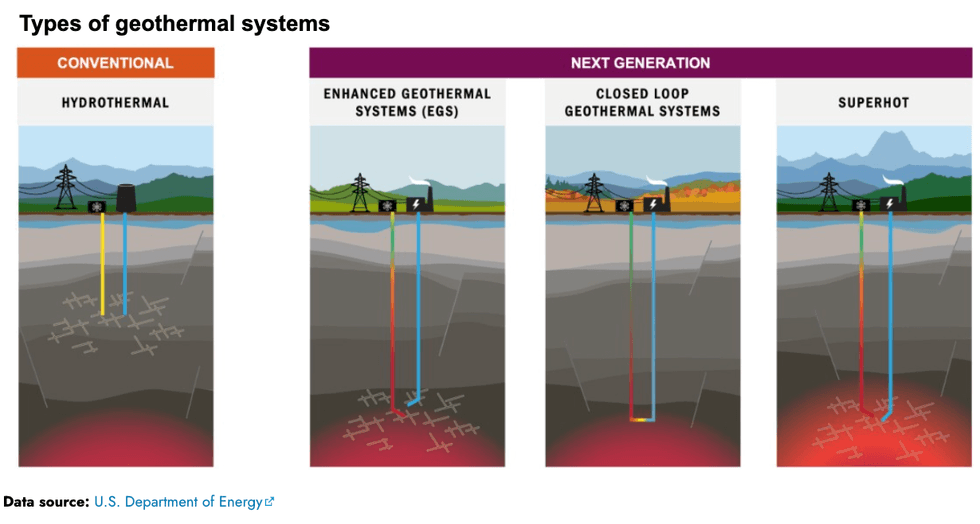

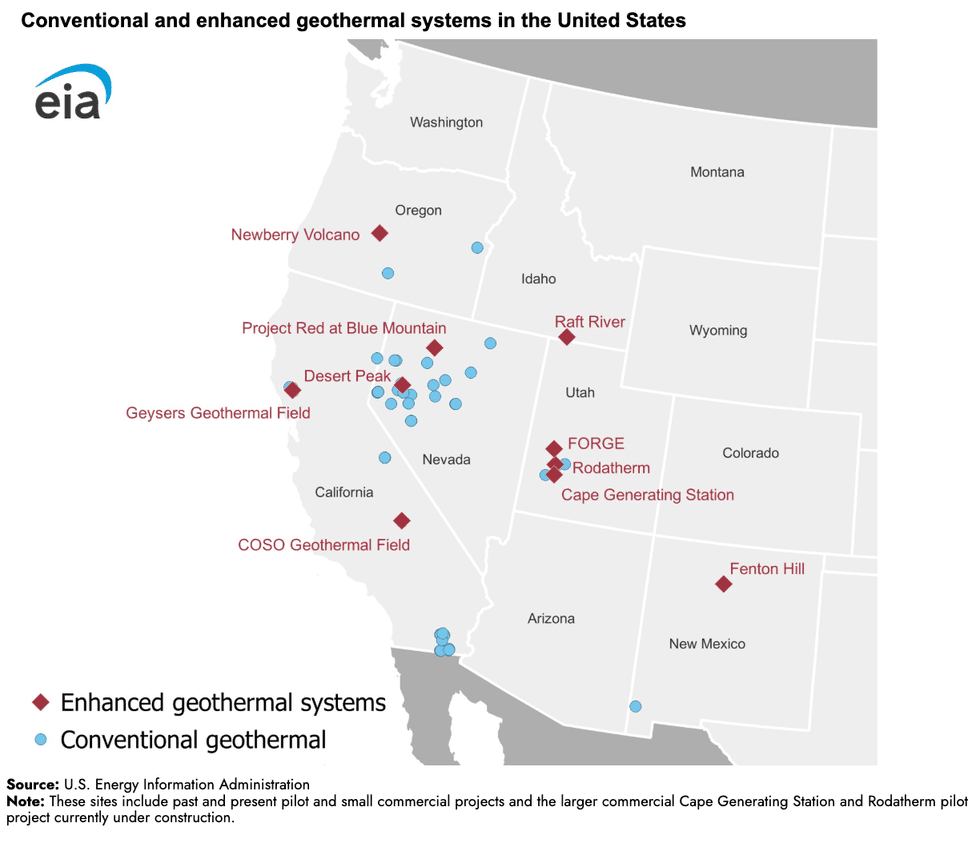

If you’re looking for a sign of the coming geothermal energy boom in the U.S., consider this: There is now a double-digit number of next-generation projects underway, according to an overview the Energy Information Administration published Thursday. For the past century, geothermal energy has relied upon finding and tapping into suitably hot underground reservoirs of water. But a new generation of “enhanced” geothermal companies is using modern drilling techniques to harness heat from dry rocks.

If you’re looking for a thorough overview of the technology, Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote the definitive 101 explainer here. But a few represent some of the earliest experiments in enhanced geothermal, including the Fenton Hill in New Mexico, established in the 1970s, which was the world’s first successful project to use the technology.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

When Exxon Mobil announced plans in December to scale back its spending on low-carbon investments, the oil giant justified the move in part on all the carbon capture and storage projects poised to come online this year that would vault the company ahead of its rivals. This week, Exxon Mobil started transporting and storing captured carbon dioxide at its latest facility in Louisiana. The New Generation Gas Gathering facility on the western edge of the state’s Gulf Coast is the company’s second CCS project in Louisiana. Known as NG3, the project is set to remove 1.2 million tons of CO2 per year from gas streams headed to export markets on the coast. The Carbon Herald reported that two additional CCS projects are set to start up operations this year.

CCS got a big boost in October when Google agreed to back construction of a gas-fired power plant built with carbon capture tech from the ground up. The plant, which Matthew noted at the time would be the first of its kind at a commercial scale, is sited near a well where captured carbon can be injected. Senate Democrats, meanwhile, are reportedly probing the Trump administration’s decision to redirect CCS funding to coal plants.

In 2019, Maine expanded its Net Energy Billing program to subsidize construction of commercial-scale solar farms across the state. “And it worked,” Maine Public Radio reported last July when the state passed a law to phase out the funding, “too well, some argue.” In 2025 alone, ratepayers in the state were on the hook for $234 million to support the program. Solar companies sued, arguing that the abrupt cut to state support had unfairly deprived them of funding. But this week U.S. District Judge Stacey Neumann denied a motion the owners of dozens of solar farms filed requesting an injunction.

That isn’t to say things aren’t looking sunny for solar in Maine. On the contrary, just yesterday the developer Swift Current Energy secured $248 million in project financing for a 122-megawatt solar farm and the Poland Spring water company went on statewide TV to show off the new panels on its bottling plant. The federal outlook isn’t as bright at the moment. As Heatmap’s Jael Holzman reported in December, the solar industry was begging Congress for help to end the Trump administration’s permitting blockade on new projects on federal lands.

The Trump-stumping country music star John Rich is continuing his crusade against the Tennessee Valley Authority. Months after blocking construction of a gas plant in his neighborhood, Rich personally pressed TVA CEO Don Moul to reroute a transmission line, posting a video Thursday of farmers who opposed the federal utility’s use of the right of way process to push through the project. Rich said Moul “personally told me as of this morning” TVA will put the effort on hold. The left-wing energy writer and Heatmap contributor Fred Stafford summed it up this way on X: “MAGA NIMBY rises, Dark Abundance falls. TVA ratepayers will be paying more for a rerouted transmission project because this country music star threw his support behind a local farmer who refuses to allow the transmission line to cross his land.”