You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

The market for fancy electric vehicles is anybody’s game.

One-pedal driving is a revelatory perk. Lift your foot off the accelerator in an electric vehicle and its regenerative braking kicks in, slowing the car while channeling recovered energy back into the battery. Once a person masters the feel, it’s possible to drive for miles on end without touching the brake pedal.

There’s just one problem: it’s jerky. During 50,000 miles in my own EV, I’ve learned to gently let off the accelerator to minimize the jostling. But, like working the clutch in a stick-shift, this is an acquired skill. The issue vexed the engineers at Rolls-Royce who wanted their electrified offering to replicate the “champagne stop” chauffeurs must master: stopping so gently that the masters of the universe riding in the back spill nary a drop of bubbly. In the end, they dealt with the aggressiveness of regen braking by turning it off.

Preservation of prosecco is a small quirk among a batch of big questions about how to electrify the luxury car. On the surface, this sounds like a simple matter: replace the gasoline guts with an electric powertrain, and you’re done. However, although the traditional luxury brands have embarked on the inevitable transition to electric, it’s a little murky just what a luxury EV is, who gets to make one, and whether the future of luxury really means never driving yourself again.

In the gasoline days there was little confusion. Toyota, Honda, and Nissan had their upscale brands (Lexus, Acura, and Infiniti, respectively) to push more plush versions of what were, fundamentally, the same cars. Brands like BMW and Mercedes-Benz offered performance alongside leather cushiness, all at a price point attainable to the upper-middle class. Porsche pushed a kind of performance-first luxury; the likes of Bentley and Rolls-Royce sold unattainable exclusivity to the 1 percent.

Along the way to the mainstream EV, definitions got a little looser. Thanks to the zippy performance, sex appeal, and high price of the Model S and X, Tesla positioned these as luxury EVs and peeled away buyers from the likes of Bimmer and Benz. Yet in terms of creature comforts, it’s hard to call a Tesla luxurious. Its spartan interior, defined by enormous touchscreens and little else, reflects the minimalist design language of Silicon Valley, not the rich Corinthian leather of old-fashioned style. Tesla has also been dogged by complaints about manufacturing inconsistencies such as thin paint and uneven door panel gaps — the kind of things that make German engineers toss and turn at night.

Elon Musk’s followers in the EV startup space are experimenting with the limits of the “luxury car,” too. Lucid’s Air is a more traditional big, posh sedan, with ridiculous power numbers and interior that tries to toe the line between LED future and maximalist past. Rivian’s R1T and R1S, meanwhile, build on the fact that pickups and SUVs have morphed from utilitarian workhorses into oversized luxury rides that command prices north of $50,000 — which happened long before EVs entered the chat. It doesn’t hurt that selling a vehicle on luxury allows a company to charge more, which brings in precious revenue a startup needs to get on its feet and helps to mask the high cost of the battery (the big challenge for anyone trying to deliver the true budget EV).

Now the traditional luxury brands are coming in force. BMW’s first mass-produced EV, the rounded-cube i3, was an avatar of the previous decade’s idea of an electric vehicle, full of design quirks meant to communicate futurism and sustainability. The i4, produced starting in 2021, looks a lot more like, well, a BMW sedan, with an interior that melds the BMW look of old (lots of buttons and fancy accents) with a 14.9-inch curved display meant to be a wow feature. The story is similar at Mercedes-Benz. Inside, it is a cushy, plush take on the LED spaceship look. From the outside, the main clue to the EQS’s electrification is the sealed-off grille. (EVs don’t need the open grille to suck in lots of air like a combustion car does, making possible the Tesla Model 3’s stark closed mouth.)

Luxury EV-makers are also learning how to pamper their prospective buyers by sanding off the rough edges of EV ownership, like range anxiety. More miles generally means more battery and therefore, more money. Pricey models from Rivian, Tesla, and Lucid allow the well-heeled buyer to reach 400 miles of range or more, and the Mercedes EQS is EPA rated to 350 miles but may deliver even more in the real world. Meanwhile, the “entry” EV is stuck with 250 to 300, and BMW’s range barely breaks the 300 mark.

Rolls-Royce is smoothing out not only its champagne stops, but also its starts. The super-luxe electric Spectre doesn’t use its monstrous torque to rocket off the line, but instead is engineered to glide from a start in a way that makes the car’s enormous mass invisible to its occupants. Meanwhile, BMW and Mercedes seem to have solved the riddle of cornering and feel in an EV, with Car and Driver saying the i4 outperforms its gasoline counterpart. (It doesn’t hurt that EVs carry their big batteries along the bottom, giving them a low center of gravity.) Hyundai makes excellent EVs, but there’s no mistaking that you’re in a BMW.

Besides comfort and performance, luxury carmakers have typically marketed their offerings on advanced technology. Here, the future of luxury EVs comes into focus. The big vehicle technology yet to come is true autonomy — after all, what's more luxurious than having someone, or something, else do the driving?

EVs and autonomous driving technologies are already intertwined, mostly because of Musk’s public insistence on Tesla’s Autopilot features and vision for full self-driving — not to mention the many public controversies about the system’s failures. Things are set to stay that way as automakers, and especially luxury ones, race to be the first to offer new features.

A recent Los Angeles Times story about Mercedes-Benz’s $45 billion move to go all-electric by 2030 notes the brand’s desire to retake the luxury EV market from Tesla, and a big part of that is by pulling ahead of Musk’s brand on autonomy. This year, Mercedes became the first brand to be given explicit permission in the U.S. to go ahead with Level 3 autonomous features in a vehicle on public roads.

Level 3 is a turning point. Levels 0, 1, and 2 in the Society of Automotive Engineers’ classification scheme include technologies now widely available in vehicles. Think of lane-keep assist and adaptive cruise control. These features lessen the driver’s burden, but they do not replace her. Levels 4 and 5 represent something that could truly be called self-driving. Level 3 is the bridge: the first time when — at slow speeds, and only under controlled circumstances on chosen roadways — the car is permitted to drive.

It’s also the most harrowing. An expert who spoke to me in February about Mercedes’ plan called Level 3 a “nightmare scenario.” The main worry is over the “handoff,” the moment when the human must be ready to retake control from the machine. Handoffs have the potential to lead to confusion over who’s in charge, and even momentary confusion on the road can have dire consequences. Some safety experts question whether we should allow Level 3 autonomy on public streets at all.

Ultimately, those fears may be moot. This technology is coming, and the future of (not) driving will be spearheaded by luxury cars as their makers jockey for technological supremacy. But even if Mercedes or another legacy car company pulls ahead in autonomous tech, they will still find the EV market a wilder, more competitive space than the staid market for luxury combustion cars ever was.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Current conditions: A train of three storms is set to pummel Southern California with flooding rain and up to 9 inches mountain snow • Cyclone Gezani just killed at least four people in Mozambique after leaving close to 60 dead in Madagascar • Temperatures in the southern Indian state of Kerala are on track to eclipse 100 degrees Fahrenheit.

What a difference two years makes. In April 2024, New York announced plans to open a fifth offshore wind solicitation, this time with a faster timeline and $200 million from the state to support the establishment of a turbine supply chain. Seven months later, at least four developers, including Germany’s RWE and the Danish wind giant Orsted, submitted bids. But as the Trump administration launched a war against offshore wind, developers withdrew their bids. On Friday, Albany formally canceled the auction. In a statement, the state government said the reversal was due to “federal actions disrupting the offshore wind market and instilling significant uncertainty into offshore wind project development.” That doesn’t mean offshore wind is kaput. As I wrote last week, Orsted’s projects are back on track after its most recent court victory against the White House’s stop-work orders. Equinor's Empire Wind, as Heatmap’s Jael Holzman wrote last month, is cruising to completion. If numbers developers shared with Canary Media are to be believed, the few offshore wind turbines already spinning on the East Coast actually churned out power more than half the time during the recent cold snap, reaching capacity factors typically associated with natural gas plants. That would be a big success. But that success may need the political winds to shift before it can be translated into more projects.

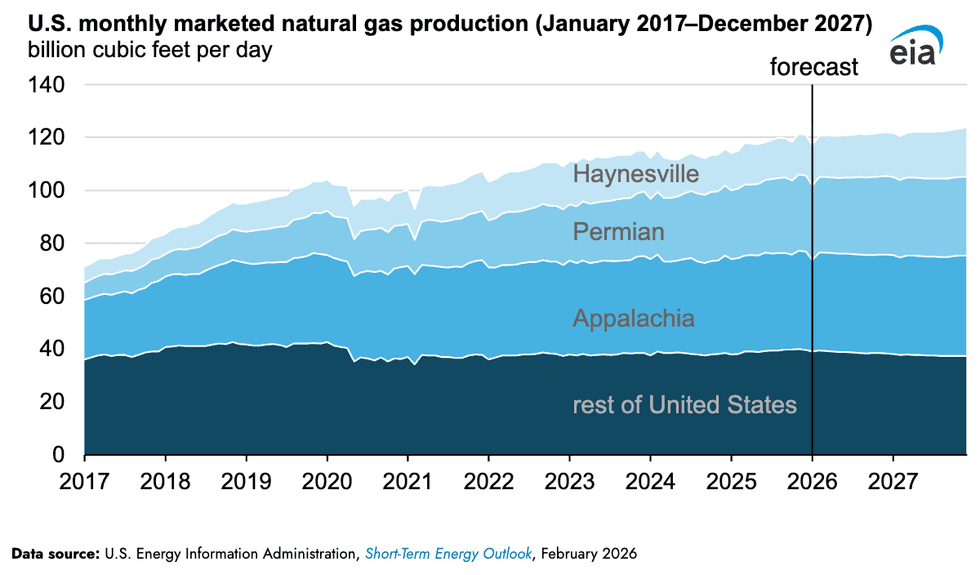

President Donald Trump’s “drill, baby, drill” isn’t moving American oil extractors, whose output is set to contract this year amid a global glut keeping prices low. But production of natural gas is set to hit a record high in 2026, and continue upward next year. The Energy Information Administration’s latest short-term energy outlook expects natural gas production to surge 2% this year to 120.8 billion cubic feet per day, from 118 billion in 2025 — then surge again next year to 122.3 billion cubic feet. Roughly 69% of the increased output is set to come from Appalachia, Louisiana’s Haynesville area, and the Texas Permian regions. Still, a lot of that gas is flowing to liquified natural gas exports, which Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin explained could raise prices.

The U.S. nuclear industry has yet to prove that microreactors can pencil out without the economies of scale that a big traditional reactor achieves. But two of the leading contenders in the race to commercialize the technology just crossed major milestones. On Friday, Amazon-backed X-energy received a license from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission to begin commercial production of reactor fuel high-assay low-enriched uranium, the rare but potent material that’s enriched up to four times higher than traditional reactor fuel. Due to its higher enrichment levels, HALEU, pronounced HAY-loo, requires facilities rated to the NRC’s Category II levels. While the U.S. has Category I facilities that handle low-enriched uranium and Category III facilities that manage the high-grade stuff made for the military, the country has not had a Category II site in operation. Once completed, the X-energy facility will be the first, in addition to being the first new commercial fuel producer licensed by the NRC in more than half a century.

On Sunday, the U.S. government airlifted a reactor for the first time. The Department of Defense transported one of Valar Atomics’ 5-megawatt microreactors via a C-17 from March Air Reserve Base in California to Hill Air Force Base in Utah. From there, the California-based startup’s reactor will go to the Utah Rafael Energy Lab in Orangeville, Utah, for testing. In a series of posts on X, Isaiah Taylor, Valar’s founder, called the event “a groundbreaking unlock for the American warfighters.” His company’s reactor, he said, “can power 5,000 homes or sustain a brigade-scale” forward operating base.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

After years of attempting to sort out new allocations from the dwindling Colorado River, negotiators from states and the federal government disbanded Friday without a plan for supplying the 40 million people who depend on its waters. Upper-basin states Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, and New Mexico have so far resisted cutting water usage when lower-basin states California, Arizona, and Nevada are, as The Guardian put it, “responsible for creating the deficit” between supply and demand. But the lower-basin states said they had already agreed to substantial cuts and wanted the northern states to share in the burden. The disagreement has created an impasse for months; negotiators blew through deadlines in November and January to come up with a solution. Calling for “unprecedented cuts” that he himself described as “unbelievably harsh,” Brad Udall, senior water and climate research scientist at Colorado State University’s Colorado Water Center, said: “Mother Nature is not going to bail us out.”

In a statement Friday, Secretary of the Interior Doug Burgum described “negotiations efforts” as “productive” and said his agency would step in to provide guidelines to the states by October.

Europe’s “regulatory rigidity risks undermining the momentum of the hydrogen economy. That, at least, is the assessment of French President Emmanuel Macron, whose government has pumped tens of billions of euros into the clean-burning fuel and promoted the concept of “pink hydrogen” made with nuclear electricity as the solution that will make energy technology take off. Speaking at what Hydrogen Insight called “a high-level gathering of CEOs and European political leaders,” Macron, who is term-limited in next year’s presidential election, said European rules are “a crazy thing.” Green hydrogen, the version of the fuel made with renewable electricity, remains dogged by high prices that the chief executive of the Spanish oil company Repsol said recently will only come down once electricity rates decrease. The Dutch government, meanwhile, just announced plans to pump 8 billion euros, roughly $9.4 billion, into green hydrogen.

Kazakhstan is bringing back its tigers. The vast Central Asian nation’s tiger reintroduction program achieved record results in reforesting an area across the Ili River Delta and Southern Balkhash region, planting more than 37,000 seedlings and cuttings on an area spanning nearly 24 acres. The government planted roughly 30,000 narrow-leaf oleaster seedlings, 5,000 willow cuttings, and about 2,000 turanga trees, once called a “relic” of the Kazakh desert. Once the forests come back, the government plans to eventually reintroduce tigers, which died out in the 1950s.

In this special episode, Rob goes over the repeal of the “endangerment finding” for greenhouse gases with Harvard Law School’s Jody Freeman.

President Trump has opened a new and aggressive war on the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to limit climate pollution. Last week, the EPA formally repealed its scientific determination that greenhouse gases endanger human health and the environment.

On this week’s episode of Shift Key, we find out what happens next.

Rob is joined by Jody Freeman, the director of the Environmental and Energy Law Program at Harvard Law School, to discuss the Trump administration’s war on the endangerment finding. They chat about how the Trump administration has already changed its argument since last summer, whether the Supreme Court will buy what it’s selling, and what it all means for the future of climate law.

They also talk about whether the Clean Air Act has ever been an effective tool to fight greenhouse gas pollution — and whether the repeal could bring any upside for states and cities.

Shift Key is hosted by Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Here is an excerpt from our conversation:

Jody Freeman: The scientific community, you know, filed comments on this proposal and just knocked all of the claims in the report out of the box, and made clear how much evidence not only there was in 2009, for the endangerment finding, but much more now. And they made this very clear. And the National Academies of Science report was excellent on this. So they did their job. They reflected the state of the science and EPA has dropped any frontal attack on the science underlying the endangerment finding.

Now, it’s funny. My reaction to that is like twofold. One, like, yay science, right? Go science. But two is, okay, well, now the proposal seems a little less crazy, right? Or the rule seems a little less crazy. But I still think they had to fight back on this sort of abuse of the scientific record. And now it is the statutory arguments based on the meaning of these words in the law. And they think that they can get the Supreme Court to bite on their interpretation.

And they’re throwing all of these recent decisions that the Supreme Court made into the argument to say, look what you’ve done here. Look what you’ve done there. You’ve said that agencies need explicit authority to do big things. Well, this is a really big thing. And they characterize regulating transportation sector emissions as forcing a transition to EVs. And so to characterize it as this transition unheralded, you know, and they need explicit authority, they’re trying to get the court to bite. And, you know, they might succeed, but I still think some of these arguments are a real stretch.

Robinson Meyer: One thing I would call out about this is that while they’ve taken the climate denialism out of the legal argument, they cannot actually take it out of the political argument. And even yesterday, as the president was announcing this action — which, I would add, they described strictly in deregulatory terms. In fact, they seemed eager to describe it not as an environmental action, not as something that had anything to do with air and water, not even as a place where they were. They mentioned the Green New Scam, quote-unquote, a few times. But mostly this was about, oh, this is the biggest deregulatory action in American history.

It’s all about deregulation, not about like something about the environment, you know, or something about like we’re pushing back on those radicals. It was ideological in tone. But even in this case, the president couldn’t help himself but describe climate change as, I think the term he used is a giant scam. You know, like even though they’ve taken, surgically removed the climate denialism from the legal argument, it has remained in the carapace that surrounds the actual ...

Freeman: And I understand what they say publicly is, you know, deeply ideological sounding and all about climate is a hoax and all that stuff. But I think we make a mistake … You know, we all get upset about the extent to which the administration will not admit physics is a reality, you know, and science is real and so on. But, you know, we shouldn’t get distracted into jumping up and down about that. We should worry about their legal arguments here and take them seriously.

You can find a full transcript of the episode here.

Mentioned:

From Heatmap: The 3 Arguments Trump Used to Gut Greenhouse Gas Regulations

Previously on Shift Key: Trump’s Move to Kill the Clean Air Act’s Climate Authority Forever

Rob on the Loper Bright case and other Supreme Court attacks on the EPAThis episode of Shift Key is sponsored by ...

This episode of Shift Key is sponsored by ...

Accelerate your clean energy career with Yale’s online certificate programs. Explore the 10-month Financing and Deploying Clean Energy program or the 5-month Clean and Equitable Energy Development program. Use referral code HeatMap26 and get your application in by the priority deadline for $500 off tuition to one of Yale’s online certificate programs in clean energy. Learn more at cbey.yale.edu/online-learning-opportunities.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.

This transcript has been automatically generated.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Robinson Meyer:

[1:25] Hi, I’m Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News, and you are listening to Shift Key, Heatmap’s weekly podcast about decarbonization and the shift away from fossil fuels. It is Monday, February 16. This is a semi-emergency episode of Shift Key. And on this show, we are talking about what else is the endangerment finding from the EPA. So at the tail end of last week, the Trump administration repealed the endangerment finding. That is the scientific determination made by the Environmental Protection Agency, the EPA, that carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases endanger human health and the natural world. It’s a big deal. This is the most aggressive attack on American climate law that I think has come out of the Trump administration so far. It is certainly the most aggressive attack on U.S. climate regulation that President Trump has ever attempted. This is more aggressive, I think, on climate change than anything they did this term or the past term from 2016 to 2020. If this were to become law and be upheld by the Supreme Court, then it would essentially undo the EPA’s ability to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act at all and leave future Democratic presidents with a much, much smaller playbook to regulate climate change.

Robinson Meyer:

[2:37] I should say, it took the Trump administration a very long time to tell us how they were actually going to do this. So on Thursday around noon, President Trump went out with Lee Zeldin, the EPA administrator, and said, we’re repealing the endangerment finding. He called climate change a giant scam. He talked about how this was this giant deregulatory action. It then took like 24 hours for the EPA to actually post legal documents saying how they were going to repeal the endangerment finding. They have now done so. And it is now, just to let you into our digital recording studio. We are recording this the very tail end of Friday, because we have finally had time to look at the documents, metabolize them, and be joined by a great legal

Robinson Meyer:

[3:17] expert who’s going to help us understand them. Joining me on this week’s show is Jody Freeman, former, future, and present shift key guest. She’s also the Archibald Cox Professor of Law at Harvard Law School and the Director of the Energy and Environmental Law Program there. And she has worked on these issues directly for a long time. She was Counselor for Energy and Climate Change in the Obama White House from 2009 to 2010. And while in the White House, she was the architect of President Barack Obama’s agreement with the U.S. Auto industry to double fuel economy standards and to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act. So this has been an issue, as you’ll hear, near and dear to her heart for a long time. And it’s always fun to talk about this stuff with her. Jody Freeman, welcome to Shift Key.

Jody Freeman:

[4:01] Great to be with you, as always.

Robinson Meyer:

[4:03] So, Jody, you worked on these issues, in fact, this exact set of legal questions in the Obama White House more than a decade ago when these decisions were made that set us up for the Clean Air Act regulating greenhouse gases.

Robinson Meyer:

[4:18] Before we get into this discussion, what do you think is the headline here? How should we think about the announcement that the Trump administration and President Trump just made?

Jody Freeman:

[4:27] So first of all, you’re right. These issues are near and dear to my heart, I have to say. I guess I’d summarize it as they’re going for the juggler, they’re swinging for the fences, any other metaphor like that. They’re going big, trying to essentially knock out the ability of the Environmental Protection agency to regulate greenhouse gases. And, you know, why does this matter? The Clean Air Act has been the main driver, the main legal vehicle for trying to control emissions of these pollutants in our economy. And it’s been the legal authority to regulate transportation sector emissions, which are the issue here in this rule, but also power plant emissions and methane emissions from oil and gas. And it’s also been the basis for our pledges to the international community. So to knock out the Clean Air Act is really consequential and serious, and they are bent on doing it.

Robinson Meyer:

[5:23] Can you lean in a bit on what the Clean Air Act has done? Because the Obama administration, right when it came in, did quite innovative regulatory work using the Clean Air I think the history, even if you closely follow these issues, the history of using the Clean Air Act to regulate climate change has been one legal battle after another. It’s been in and out of the courts. It seems like there’s always fighting about something. The Supreme Court’s always curtailing or hearing arguments that then don’t actually matter because the administration changes. How has the Clean Air Act actually reduced greenhouse gas emissions since 2009?

Jody Freeman:

[6:07] Well, that’s a big question. And it’s a very important question because you’re right. The headline of the Clean Air Act is one battle after the other. But you might also say that’s because it’s such a consequential law. I mean, it’s a major statute to protect American public health. That’s really what this law was passed to do in 1970 and to allow the EPA to regulate harmful pollution. And the only part of what you said in your description there that I might take a little bit of issue with is that it was innovative to address greenhouse gases. I’m not so sure. I think it follows in the pattern of what the Clean Air Act was set up to do.

Jody Freeman:

[6:47] There was an open question, are greenhouse gases a pollutant under the law? Do they fit the definition of what Congress meant when they

Jody Freeman:

[6:57] Defined that term pollutant, that was the open question back in the George W. Bush administration. And it was decided in Massachusetts v. EPA, the famous Supreme Court case that yes, greenhouse gases are pollutants regulable under the act. And that meant they would be treated like other pollution. And so back in the Obama administration, we took the EPA decision seriously and said, okay, now what are the legal steps we have to follow if greenhouse gases are pollutants? And the other question in Mass v. EPA was, could the Bush administration at that time refuse to make a finding that this pollution endangers the public health and welfare for the reasons that it set out? It didn’t want to do that because it knew that making an endangerment finding, that’s what it’s called, would lead to a requirement that they set standards. And they didn’t want to do it. So when the Obama administration came in, we said, well, we do need to make this finding. The science supports it. Greenhouse gases do harm public health or welfare of Americans, not just others, not just globally. And if we make that finding, we’re obligated to set standards first for cars and trucks. And that’s what we did. And the idea is just to control pollution from the cars, just like you would any other pollution from the cars, which makes them cleaner over time.

Jody Freeman:

[8:14] And I think the law, you know, Rob, you asked about what it’s done. I think this law has proven very effective at cleaning up harmful pollution from cars, trucks, and other transportation sources. And I think it’s helped to drive the power sector, you know, power plants toward a decarbonization agenda as well. I actually think it’s been very successful as a lever here to advance cleaner production, cleaner vehicles,

Jody Freeman:

[8:45] Cleaner systems for producing electricity, I think it’s been a major component of what has made the U.S. start to clean up its act, for lack of a better word, in terms of GHG emissions. It was never meant to be the only instrument. You know, the Clean Air Act is one statute. It’s a powerful statute. I think it’s been a hugely successful statute overall in terms of public health generally. You know, there are studies that show that while Clean Air Act regulations can be very expensive, the expenses, the costs are dwarfed by the benefits to the public. And so that’s really important to cite because this is part of why it’s one battle after another. They’re really important rules. They affect really powerful industries. They sue all the time and always have historically going back to the 1970s. There’s nothing new about that. Any major air rule is going to be litigated. And so it is in fact trench warfare, you know, and it has been for decades, I think climate change introduced a new level of contentiousness. There are folks who lost the battle over Massachusetts v. EPA who never thought greenhouse gases ought to be regulated under this law, essentially have never given up. And the truth is, I think they’re largely behind this proposal. They’re now in the Trump administration. And their argument is, they’re not explicitly calling to overturn Massachusetts v. EPA, but the arguments really are a rehash of the losing arguments.

Robinson Meyer:

[10:14] And to some degree, like a number of other Trump regulatory decisions, including what they’ve attempted actually successfully at this point or nearly successfully at this point with independent agencies, what they’ve attempted in some parts of labor law, they’ve basically taken an extremely aggressive regulatory action, acting as if they’ve won a landmark Supreme Court case, and then turned to the Supreme Court and said, don’t you want to give us this landmark ruling that will allow us to actually go do this? Like, it’s an invitation to the Supreme Court to deliver them a landmark ruling, even though the Supreme Court had not yet done so.

Jody Freeman:

[10:51] Yeah, how you put that is so right and so interesting. The idea is they can read their audience. They know they’ve got a new Supreme Court composed of different kinds of justices than back in 2007 when the Mass v. EPA case was decided. They know that all the justices that voted in the majority in that case to say greenhouse gases or pollutants and to say if you make the endangerment finding has to be based on science, they’re gone. And they know they’ve got three justices from the dissent, including the chief, that they are targeting. And they think they have a sympathetic audience and maybe can attract a couple more votes. And what they’re arguing now is a version of or cousins to the kinds of arguments they made in that case that didn’t win at the time, but they think they can win now.

Jody Freeman:

[11:36] And there’s some nuance to what they’re saying. They’re saying two main things.

Robinson Meyer:

[11:39] I was going to say, so let’s get into it. What are they arguing in the legal brief? Because, and before we even get into it, we should say, the president announced that they were repealing the endangerment finding at like 1:30 p.m. on Thursday, and they did not actually release the documents to do it until about 24 hours later. So we’ve only had, at the time we record this, just the end of the day on Friday, we’ve only had these documents for a few hours. But what is their legal argument that they’re making?

Jody Freeman:

[12:05] Just to say, this is a huge package. This is, you know, hundreds of pages, but here’s a super simple summary. There’s a section of the Clean Air Act that says that EPA has to set emission standards for vehicles, cars and trucks to control their pollutants. If those pollutants contribute to air pollution that endangers health or welfare. So there’s two parts of that. First, you decide, is there air pollution that endangers public health or welfare? That would be greenhouse gases in the atmosphere that create global warming that cause harms. That would be the air pollution that endangers health or welfare. And then the first question you ask is, do emissions from our cars and trucks contribute to that? And in 2009, EPA said yes. And the scientific record supports both of those. And now the EPA is saying that’s wrong for two main reasons. First, the quote-unquote air pollution that endangers public health or welfare, well, that’s global pollution. And we can only regulate local or regional pollution that creates direct harms. So we don’t have the authority to regulate that air pollution. Now, that argument seems to conflict directly with Mass v. EPA that said greenhouse gases are pollutants, but it never technically addressed what air pollution was.

Jody Freeman:

[13:28] It said GHGs are pollutants, but it didn’t say it’s air pollution that endangers health or welfare. See my point? So there’s this subtle linguistic difference here, and they’re all over that. And their argument is really a rehash of saying this law is really just about local pollution. And if the court were to go for that argument, they’d be saying, right, EPA can’t regulate anything other than local pollutants. And so essentially that would overturn Mass v. EPA. Okay. The second part of their argument is, and it’s separate. So they all sort of, they want them to stand alone.

Robinson Meyer:

[14:05] They’re saying- And they kind of have set this up so that they could say, well, if you don’t like this argument, you could go for this argument and it would also.

Jody Freeman:

[14:11] Prove- It’s a box of chocolates and the Supreme Court can take whatever chocolate they like. So the idea is Well, even if, you know, we can regulate global pollution that creates an endangerment, we don’t contribute to it. Car and truck emissions don’t contribute to it. They’re just such an infinitesimally, fractionally small share of global emissions. They don’t make a dent. That’s not a contribution. You know, for something to be a contribution, their argument is it has to be enough that if you were to reduce our contribution, it would make a difference and it won’t. Their argument is it doesn’t matter that nothing we do can make a dent in global climate change and the harms the flow from it and so it’s futile they say it’s futile to do it and they jump ahead to setting standards which is not part of this analysis but they sort of merge the next step which would be setting the standards into their analysis when they say and you know doing it would be hugely costly for the American consumer and have all these problems and so they actually lumped two parts of their legal obligation together to help them out.

Jody Freeman:

[15:18] And while at the same time, splintering another part of the analysis to help them out by saying, you know, the way we’re looking at contribution is we look at each category and class of motor vehicle. We shouldn’t consider all the cars and trucks, all the new cars and trucks. We should slice and dice them. Because when we slice and dice them,

Jody Freeman:

[15:37] you see that the share of emissions is so, so nothing. It’s so little so they sort of divide things up when it suits them when it helps them and they merge stuff when it helps them and the collection of arguments is one way or another supreme court we’re either too small a share of this to matter and it’s futile or we don’t even have the authority in the first place to deal with this problem and we would like you very much to shut us down so that no future administration can do this if they want to

Robinson Meyer:

[16:06] And if the future administration is really the way we should think about the ultimate legal consequences of this, of this derogatory action and the Supreme Court case that could potentially result, because to be clear, this, the Trump administration is not going to come out with some kind of future rule on tailpipe pollution or power plant pollution before 2028. This is all about taking away regulatory authority from a future likely Democratic president, right?

Jody Freeman:

[16:33] Right. That’s a key insight because we all know that we’re not going to see any climate regulation out of this administration and we’re going to see the opposite, right? They’re trying to stymie renewable energy. They’re trying to revive coal. They’re going in the exact opposite direction. But that’s what I mean when I say swing for the fences or going for broke. They’re really trying to stop the future administrations from using the Clean Air Act without having Congress amend the law. You know, they’re trying to set it up. So you need a congressional amendment to authorize this regulation. It’s really important to note the Supreme Court has never shown any interest in upsetting the endangerment finding. That’s considered to be the basic scientific finding that undergirds all greenhouse gas rules in the Clean Air Act. And while they’ve narrowed the EPA’s authority to set standards in certain situations or to set it using a certain method that the EPA preferred, like EPA was using a method for power plants that the court rejected and said, you can’t set up a rule that shifts generation from dirty sources to clean sources and so on. The Supreme Court has rejected certain approaches EPA has taken, but they’ve never in all these cases since Mass v. EPA been interested, it would seem, in upsetting the endangerment finding. So it’s odd, right, that they would do so now, but the EPA now thinks they might have a sympathetic audience.

Robinson Meyer:

[17:49] I remember talking to Trump officials during the first Trump administration and the feeling, I mean, this was an earlier class of Trump oil and gas official. But I think their feeling at the time was like touching the endangerment finding, that’s going to be a mess. Like we don’t need to do that and we don’t want to do that because that’s going to really get us into hot water if we were to lose.

Jody Freeman:

[18:12] Can I say one thing about that,

Robinson Meyer:

[18:13] Though? Yeah, please. Yeah.

Jody Freeman:

[18:14] Because what you’re saying is really important. It gets to why they dropped one of their arguments. You’re exactly right. I think historically people have said the science is so solid on greenhouse gas causing global warming and the harms that flow from it are only getting clearer and worse that nobody would want to take issue with the science. But what they’ve done here is say, well, we thought we’d attack the science. Our proposal attacked the science, but we’re dropping all that. And this final rule rests on interpreting the law in the ways I described to say, well, it all turns on what a contribution is and it’s too small. It all turns on the meaning of air pollution and it should be local. And they affirmatively say science has nothing to do with that. We’re not interested in the science. Now, of course, they’re wrong about that. Science does have something to do with that. In fact, the National Academy study that came out in August that updated climate science concluded very clearly that the severity of climate impacts gets worse with every additional ton. So small shares do matter, but they’re trying to say the scientists have nothing to do. This is all legal interpretation.

Robinson Meyer:

[19:19] It’s so funny because we were just about to talk about this, where one key argument that we thought they were going to use because they used it in the proposal, they’ve completely dropped out of this document. And that is this argument about climate science, where the Department of Energy kind of got together this set of, I think they’re often referred to as contrarian. They are the most out there kind of ideological set of seven or eight climate scientists who take some distinction with the official lot, with I think what scientific consensus is, where they say, well, actually, if you look at this particular record, we should be thinking about differently. If you look at this particular statistic, that actually pokes this tiny hole in the way that people like to word these conclusions. And once you poke that tiny hole, we really can’t say whether the climate is changing at all. Now, I do think, I did not originate this line of thinking, but I think it’s a true one. If you read between the lines of this DOE contrarian science report that they put out last year, you actually can still make an affirmative case for the endangerment finding because they are unable, they have to cite existing science and they are unable to knock it all down. And from the existing science they leave standing, I think you can go and say, oh, that sounds like carbon dioxide is a big problem. Maybe not as big of a problem as other people think, but still a big problem we should do something about and someone that’s dangerous. But they’ve totally dropped it.

Jody Freeman:

[20:45] There are so many problems with this. So first of all, it was, like you say, a handful, I think it was five. Now, these scientists and one I think is an economist, they were published in peer-reviewed journals, but they were considered to be far outside the mainstream and their claims have been debunked in the past already. So they were already known to be, as you say, the contrarians. But the problem is DOE handpicked these people. They didn’t create a balanced review process. In fact, they canceled the government’s normal multi-agency review process. So it already looked really suspicious. And then they came out with this report that was just, I mean, just so completely misleading and cherry picked and so on. Now, a federal court has held that the process DOE used violates federal law. So that’s number one. So that’s a problem. And then they scattered, like they disbanded and ran away.

Robinson Meyer:

[21:30] Yeah, rather than try to defend it, they were just like, actually, this is all over. We’re done with this.

Jody Freeman:

[21:34] So it’s not a shocker that EPA concluded that to rely heavily on this would just invite judicial overturning, right? Or at least the eyebrows would go up in the courts and make them look like they were so off base. And it might sort of lead to more skepticism about the rest of their arguments, right? So it makes some sense that they dropped it. The other feature I have to give a lot of credit to the scientific community.

Jody Freeman:

[21:56] You know, filed comments on this proposal and just knocked all of the claims in the report out of the box and made clear how much evidence not only there was in 2009 for the endangerment finding, but much more now. And they made this very clear. And the National Academies of Science report was excellent on this. So they did their job. They reflected the state of the science and EPA has dropped any frontal attack on the science underlying the endangerment finding. Now, it’s funny. My reaction to that is like twofold. One, like, yay science, right? Go science. But two is, okay, well, now the proposal seems a little less crazy, right?

Jody Freeman:

[22:38] Or the rule seems a little less crazy. But I still think they had to fight back on this sort of abuse of the scientific record. And now it is the statutory arguments based on the meaning of these words in the law. And they think that they can get the Supreme Court to bite on their interpretation. And they’re throwing all of these recent decisions that the Supreme Court made into the argument to say, look what you’ve done here. Look what you’ve done there. You’ve said that agencies need explicit authority to do big things. Well, this is a really big thing. And they characterize regulating transportation sector emissions as forcing a transition to EVs. And so to characterize it as this transition unheralded, you know, and they need explicit authority, they’re trying to get the court to bite.

Jody Freeman:

[23:28] And, you know, they might succeed, but I still think some of these arguments are a real stretch.

Robinson Meyer:

[25:09] One thing I would call out about this is that while they’ve taken the climate denialism out of the legal argument, they cannot actually take it out of the political argument. And even yesterday, as the president was announcing this action, which I would add, they described strictly in deregulatory terms. In fact, they seemed eager to describe it not as an environmental action, not as something that had anything to do with air and water, not even as a place where they were. They mentioned the Green News scam, quote unquote, a few times. But mostly this was about, oh, this is the biggest deregulatory action in American history. It’s all about deregulation, not about like something about the environment, you know, or something about like we’re pushing back on those radicals. It was ideological in tone. But even in this case, the president couldn’t help himself but describe climate change as I think the term he used is a giant scam. You know, like even though they’ve taken, surgically removed the climate denialism from the legal argument, it has remained in the carapace that surrounds the actual.

Jody Freeman:

[26:12] And I understand what they say publicly is, you know, deeply ideological sounding and all about climate is a hoax and all that stuff. But I think we make a mistake … You know, we all get upset about the extent to which the administration will not admit physics is a reality, you know, and science is real and so on. But, you know, we shouldn’t get distracted into jumping up and down about that.

Jody Freeman:

[26:34] We should worry about their legal arguments here and take them seriously.

Robinson Meyer:

[26:38] How much does this whole argument rely on the major questions doctrine, which is this recent Supreme Court idea or doctrine that if the government, seemingly usually democratic administrations want to do something ambitious under a law that’s already on the books. They’re not allowed to.

Jody Freeman:

[26:58] Well, they need express authorization.

Robinson Meyer:

[26:59] They need express authorization from Congress.

Jody Freeman:

[27:01] And that’s a bit of a trick because many statutes, including the Clean Air Act, broadly delegate authority to agencies, especially when those agencies have to address public health concerns or safety concerns where there’s changing technology over time. The statutes are drawn broadly by Congress specifically to leave room for the agencies to adjust to new developments over time. But the court has now said broad authority isn’t clear enough. You need pointed express authority, and we don’t really know what will qualify, right? It would mean Congress has to be prescient and say, one day there will be something called global climate change, and you should address that too, right? So that is sort of an aspect of this that makes it really hard for Congress to ever anticipate that conditions will change and give authorities power. When you ask how big a deal is this doctrine playing, I think that they could win without it. They don’t need to succeed. It would be a knockout blow to say, look, whatever you think about climate change and whatever you think about cars contributing to it, the bottom line is this agency, meaning us, they’re saying that about themselves. This would be such a big deal to do that we want the Congress to tell us again that we should do it very clearly. That’s a knockout blow. That says, send this back to Congress. It invites the court to really say, we don’t need to get into the details. We just think that’s true. And we’re going to stop the agency there.

Robinson Meyer:

[28:28] I think one line that’s worth pulling out that came out in some of your earlier comments that I just want to spell out for listeners is like the power plant, you know, the Clean Air Act, can be used on any number of polluting facilities or polluting technologies. But the two that are responsible for the most emissions and the two that there’s been the most regulation about are cars and trucks, moving vehicles, and power plants. And what happened first, what Mass v. EPA is about, is whether California or the EPA could regulate greenhouse gas emissions from cars. And regulating greenhouse gas emissions from cars has actually been relatively straightforward. Forward and the automakers have accepted it, it’s then taking that and apply taking the fact that you can regulate greenhouse gas emissions and applying it to power plants that has been the thing that’s bumped in and out of the courts for the, you know, 15 years.

Jody Freeman:

[29:21] Well, I agree with you that regulating car and truck emissions is really very straightforward. And on top of it all, it doesn’t really meet the test for being a, quote, major question, because this is something EPA has done since the 1970s. They set standards for auto manufacturers that they have limits on how much pollution per mile the cars can produce. And that’s just very well understood. And it definitely forces internal combustion engines to get cleaner over time. And it has driven some additional plug-in hybrids and battery electric vehicles. But this idea that it’s forcing an abandonment of the internal combustion engine and everybody has to drive an EV is false. And even the EPA’s most ambitious car and truck standards issued under the Biden administration had a very significant share of internal combustion engines still. Nobody is forced to drive anything they don’t want to drive.

Robinson Meyer:

[30:11] I just want to say that very clearly. That’s right, though. I do think that the Biden administration, or at least there’s some political messaging that like they didn’t help themselves there, where these things initially come out. They want to describe, they want, and the Biden administration wants to show to environmental groups and environmentalists how far it’s going.

Jody Freeman:

[30:28] This is the tension. You have a Supreme Court that says, major questions, watch out. You shouldn’t do transformative stuff without express authority. You have politicians standing up to say, look how transformative we are. And not a great media strategy if it’s going to come back to bite you in court.

Robinson Meyer:

[30:45] Well, and ultimately what this may require is environmental groups that can translate for politicians. So politicians can say, we’re actually doing completely boring and uninteresting stuff with the power sector and with cars. You don’t need to worry about it at all. It’s not going to change your life. And then environmental groups can be, they’re actually really going to reduce emissions a lot.

Jody Freeman:

[31:03] The other thing I just want to mention is that in this rule, EPA is making a lot of this case called Loper, Loper Bright, which overturned the very famous Chevron doctrine. And all that means, I mean, people may have been following this. I think you probably have talked about it on your show.

Jody Freeman:

[31:18] All that new case Loper means is that courts will interpret statutes, and there’s no deference to agencies when the language is ambiguous, okay? When the language is ambiguous, the courts will decide. But sometimes the language will give the matter to the agency. Sometimes the matter will delegate the discretion to the agency, and that instance is happening here because this section of the law says in the administrator’s judgment, you know, does the pollutant contribute to air pollution and so on. So they’re trying to suggest that this Loper case changes everything and somehow it should lead them to rethink what they did in Massachusetts v. EPA. But that is completely wrong because, bear with me here, in Mass v. EPA, the court expressly cited the prior cases that raised this major questions idea. And they rejected that argument and said, no, this statute’s clear. This statute means one thing. And the one thing is pollutants include greenhouse gases. So this sort of thing about Loper Bright and rejecting Chevron, it’s sort of beside the point because the court has said the law is already clear.

Robinson Meyer:

[32:37] And I would say that in the course of reporting the story, I’ve actually been surprised by how clear the law is, how clearly the law does seem to apply to greenhouse gases. There’s this term of art that’s in the law, which is welfare that I think we summarize in our story is like the natural world. But when you look at the law, the law is like, this is about soils. This is about water. This is about vegetation. This is about animal life. This is about human property. This, it’s about the climate. Like, the law is quite clear.

Jody Freeman:

[33:05] Your wellbeing and economics.

Robinson Meyer:

[33:07] Yeah. And welfare is meant that this other term that, you know, does a certain pollutant endanger human health or welfare, that welfare should be taken extremely expansively.

Jody Freeman:

[33:18] The bottom line here is, you know, there are folks who are deeply committed

Jody Freeman:

[33:23] to the idea that this law should never have been used to do anything about climate change. It was a misapplication, and they’re back fighting that fight. I don’t agree with that. I think the statute is perfectly capable of being legitimately used to address climate change because I do think greenhouse gases fit the definition of pollution. If you want to fight about how stringent the standard should be, that’s something to have a discussion about. But the Act also addresses that. When EPA sets the standards for cars and trucks, when it sets the standards for power plants, they have to consider cost. They have to consider technological feasibility. They have to consider lead time when it comes to cars and trucks. In other words, Congress thought about making sure the agency couldn’t do extreme things without considering the implications. So I do think this is a rather well thought through statute and its application, at least to cars and trucks. The issue we’re talking about, as you said, is pretty straightforward.

Robinson Meyer:

[34:18] Let’s say that the repeal is upheld, that the Supreme Court says that actually, yes, the Clean Air Act doesn’t apply to greenhouse gases. Does that have unintended upside for state or local governments? Because one thing that started to some climate activists or climate groups have started to say is like, look, states and local governments have wanted to pass laws penalizing oil and gas companies or finding some kind.

Robinson Meyer:

[34:43] Of responsibility for oil among oil and gas companies for climate change. The argument that oil and gas companies, fossil fuel companies have made in court is like, look, we’re actually not responsible in these kind of common law terms or under this part of the law, because the Clean Air Act regulates greenhouse gases. And therefore, we have legal immunity at the state and local level and from civil law claims, because this is actually a federal issue. And as long as the EPA is regulating greenhouse gas, we can’t be found liable for that. If the Supreme Court were to go in and say, okay, actually, clean air doesn’t apply to greenhouse gases, does that create this legal opening? Or can the Supreme Court just as easily close that opening the moment they create it?

Jody Freeman:

[35:25] This is a hard question because those lawsuits that have proceeded to some extent, the sort of nuisance cases seeking damages or some other remedy because of power plants or oil and gas companies’ contributions to emissions, they have largely failed because of a causation problem proving the linkage between those emissions and the impact that’s a hard thing to do in tort law right the chain of causation the other reason you cited is also real which is we have another supreme court decision that says when congress delegates greenhouse gas regulation dpa under the clean air act plaintiffs can’t come into federal courts and plead nuisance cases. Those cases are precluded. The federal court common law claims are precluded by the Clean Air Act, which gave the matter to the EPA.

Jody Freeman:

[36:16] You’re saying, well, if the court says it doesn’t belong with the EPA, maybe they can come back into federal court and file these nuisance claims again. I have no doubt that a decision that holds, if it were to happen, that the Clean Air Act doesn’t cover greenhouse gases would unleash a chaotic barrage of litigation. But I’m not sure all of that succeeds, partly because there are complicated landing spots where the court could wind up saying something as thread the needle-ish as, well, EPA still has authority to regulate greenhouse gases as pollutants. That’s true. But in this instance, it doesn’t reach the contribution threshold that would be required. It’s not a significant enough contribution so EPA can choose not to regulate because it’s too small a share of the global problem. And that leaves us in this no man’s land of

Jody Freeman:

[37:08] EPA still owns the regulatory issue, but it does nothing about the regulatory issue. And somebody might argue, well, too bad, you’re still precluded, right, from bringing federal common law claims. So I don’t know how that will all play out, but I can guarantee you that certainly there will be follow-up litigation, you know.

Robinson Meyer:

[37:27] Would that, I guess, would that apply? There’s another kind of local climate action we’ve seen lately, these climate superfund laws where a state says, if you sold oil and gas in our state a certain amount, you have to pay into a fund that will then use for climate adaptation. I mean, does, would that kind of...

Jody Freeman:

[37:45] Those are already being attacked by the administration, right? Which argues that they’re unconstitutional and that will play out. I guess I’m not a fan of us pursuing a strategy of exclusively litigation. I think we have to have a strategy of what does new legislation look like, whether or not this case winds up coming down in favor of the Trump administration or they lose. Because let’s face it, the Clean Air Act is a magnificent instrument and very

Jody Freeman:

[38:16] useful for controlling pollution that harms Americans, including greenhouse gas pollution. But it was never meant to do everything on its own. It was never meant to get us everywhere we need to get to address climate change and the harms that flow from it, both mitigation and adaptation. It was never meant to be the only tool that would help us accomplish an energy transition. So it’s time, regardless of this rule rescinding the endangerment finding, regardless of what happens to it, for us to think about new approaches. So that means new legislation when we get an administration and a Congress that wants to do something about this issue, new state level initiatives, new ideas about how to get capital into the market to support renewables and alternatives. And so we have to rethink the whole package of policy approaches. That’s my message, that the Clean Air Act cannot bear the weight that people want to put on it.

Robinson Meyer:

[39:10] And it does seem like if the Supreme Court were to rule that the EPA does get to regulate greenhouse gases, but it can’t do anything about them. That’s like the apotheosis of where they’ve been trying to get for the past 15 years. They’ll finally have done it. They’ll finally have figured out how to.

Jody Freeman:

[39:25] I hope it doesn’t come to that.

Robinson Meyer:

[39:26] The perfect John Roberts decision.

Jody Freeman:

[39:28] And I also want to just defend the Clean Air Act as this law, you know, this historic law, because even if you, if as you pointed out, the power plant standards never got implemented. Right. Like in the Obama administration, they created the clean power plan to try to transition these power plants to cleaner energy. And the court struck it down. Right. Now, this took a long time before they reached it and struck it down. It had never been implemented. And you could say, well, that was a total failure.

Robinson Meyer:

[39:53] They didn’t really strike it down until they put it on the back burner. And then Biden won. And they were like, actually, we’d like to rule on this. We don’t think it’s legal. Yeah.

Jody Freeman:

[40:00] But the point of all this is to say you can make an argument. Well, look, this act hasn’t panned out. Right. We never got these power plant standards anyway. I would just disagree with this. Number one, we’ve had two to three generations of vehicle standards that have helped drive cleaner cars, okay, already saving many, many millions of metric tons of pollution, but also reducing costs for consumers who don’t have to spend as much for gas at the pump, like FYI. So they’ve been very successful with car standards to date. They also, even the so-called failed clean power plan, that process helped to spur a decarbonization conversation among utilities and in the states that helped them plan for the future and was really consistent with the market going in the direction of cheaper renewable energy, solar, wind, et cetera. So I still think the process around the clean power plan was really productive and helpful. And I would give a lot of credit to the Clean Air Act here. Likewise, with methane leaking from oil and gas facilities regulating that getting the oil and gas companies in a conversation about cleaning up their own leaks a valuable product so Even if when we move forward, we’re going to need a new suite of tools, I think we have to give a lot of credit to how the Clean Air Act performed in the first generation of climate regulation.

Robinson Meyer:

[41:20] I’m looking forward to talking about those new tools and what could happen. But for now, we’re going to have to leave it there. Jody Freeman, thank you so much for joining us on Shift Key. Thanks so much for listening. That will do it for our show this week. You can follow me on, as always, on X at @robinsonmeyer or Bluesky or LinkedIn at my name. If you enjoyed Shift Key, leave us a review on your favorite podcast app or send this episode to one of your friends, your most clean, air-act, concerned friend. We’ll be back later this week with a new episode of Shift Key. And until then, Shift Key is a production of Heatmap News. Our editors are Jillian Goodman and Nico Lauricella. Multimedia editing and audio engineering is by Jacob Lambert and by Nick Woodbury. Our music is by Adam Kromelow. Thank you so much for listening and see you soon.