You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Chatting with RE Tech Advisors’ Deb Cloutier about data centers, lifecycle costs, and the value of federal data.

Last fall, my colleagues and I at Heatmap put together a comprehensive (and award-winning!) guide on how to Decarbonize Your Life. Though it contained information on everything from shopping for an EV to which fake meats are actually good, as my colleague Katie Brigham noted, “an energy-efficient home needs energy-efficient … gadgets to fill it up.” So we also curated lists of climate-conscious stoves, heaters, and washer-dryers — recommendations we made by talking to experts, but also by looking closely at appliances’ Energy Star certifications.

You’ve probably relied on these certifications, too. Overseen by the Environmental Protection Agency, Energy Star labels are recognized by 90% of Americans as indicating that an appliance is top of its class when it comes to saving electricity and money. According to the government’s estimates, the voluntary program has saved Americans $500 billion since it began in 1992.

But now all that appears to be reaching its end: Last week, EPA leadership told staff that the division that oversees the Energy Star efficiency certification program for home appliances will be eliminated as part of the Trump administration’s ongoing cuts and reorganization (although the president has also long pursued a vendetta against low-flow showerheads and dishwashers that “don’t work”).

To better understand the ramifications of such a decision, I spoke this week with Deb Cloutier, the president and founder of the sustainability firm RE Tech Advisors and one of the original architects of Energy Star. She provided technical guidance and tools as a consultant during the program’s development stages of the program, and later worked as a strategic advisor for the Department of Energy’s Better Buildings Initiative. Our conversation has been lightly edited and for length and clarity.

You’ve been involved in the Energy Star program since the beginning. Can you tell me a little about what the atmosphere was like when it was established back in 1992? Was there resistance to it from appliance manufacturers or Republicans at that time?

Energy Star represented a voluntary public-private partnership, meaning a nonregulatory approach to engaging the business community and catalyzing the adoption of strategic energy management. So at the time, it was the first of its kind. I wouldn’t say folks were just like, “Yes, let’s do this.” It was really new and different.

The other thing is that at that time, we had come out of the oil crisis of the 1970s, and people were starting to recognize the importance of where and how our energy was being produced. But we weren’t focused on thinking about it as an opportunity. For office buildings, the single largest controllable operating expense is your energy or utilities expenses; if the Environmental Protection Agency or the government could build awareness, develop tools, and help businesses understand how they could invest in energy efficiency and how that would translate to financial performance results for them — it was a great experiment. And it turns out that it’s the single most successful voluntary program we’ve had to date, saving over $5 billion annually.

It’s clear how losing Energy Star would harm consumers, but I’m curious to hear from you about how this is also bad for building owners and residents. What is the cost of losing this program, especially from a climate perspective?

The most important contribution of the EPA’s Energy Star program is that it has created a national standard to benchmark and measure efficiency and energy performance. You can’t manage what you don’t measure, and consistency across building types, ages, and sizes — it’s pretty complicated to make an apples-to-apples comparison.

One of the tools and resources that Energy Star has created, which I see as being embedded in the fabric of American businesses, is their benchmarking tool called Portfolio Manager. It is tied to dozens of state and local jurisdiction policies and legislation that range from building energy disclosure to mandatory best practices to maintaining and operating buildings and emissions thresholds. So the Energy Star rating system is tied not only to how organizations assess their whole building performance, but also to how it tracks and measures progress towards efficiency improvements and then gives a certification or recognition for the most highly efficient ones.

Another thing folks tend not to consider is the relationship between energy efficiency and grid stability. Energy Star-certified appliances, homes, buildings, and industrial facilities help to reduce peak demand, which improves grid stability and resilience. It also lowers the risk of brownouts and blackouts. Think about the growing demands of data center computing and AI models — we need to bring more energy onto the grid and make more space for it. People sometimes don’t realize that it is really dependent on a consistent, impartial standard as a level setting.

If you look at some of the statistics, they’re projecting that investments in new data centers will grow at more than a 20% compound annual growth rate, and that’s equal to $59 billion. It’s just astronomical how much more energy demand there will be. If you try to put that on top of a grid that is fairly antiquated and very inefficient in the way it generates, transmits, and distributes energy, then you are intensifying the potential problem.

I’ve heard about manufacturers or an outside energy or appliance group possibly setting up a replacement program if Energy Star is eliminated. What is the advantage of having the government specifically oversee Energy Star?

Three or four things make the federal government the most unique entity and the most well-equipped to oversee the Energy Star program. First, they have access to large data sets using CBECS, the Commercial Building Energy Consumption Survey, and RECS, the Residential Energy Consumption Survey. The government inherently is an impartial, unbiased group, and entities are willing to share their data with it, and that would not be the same if it were a third party or a privatized group. That data set is instrumental in creating the standards that allow you, for products, to evaluate the most energy efficient, or for buildings, to develop a one-to-100 score. Energy Star allows the top 25% to be recognized as exemplary energy performance.

The government also has access to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory resources; they have the data, and I believe they have the impartiality and the trust. Today, the Energy Star brand has over 90% consumer recognition. I would be concerned if manufacturers or others would produce confusion in the marketplace related to a single little blue label.

Is there anything consumers should know about making decisions or navigating their choices if we return to a pre-1992 landscape?

In the absence of an Energy Star label, one thing we can do is help consumers understand that it is not just about the first cost of a dishwasher or a washing machine or renting an apartment. It’s about total lifecycle costs. What the Energy Star label does is it helps you have confidence that [an appliance] will use the least amount of energy necessary to run over its lifetime. But if your product or apartment is full of less efficient appliances, you have to think about how much more energy you will pay for over that life cycle. That’s sometimes a difficult concept for folks to understand: They think of their first cost, not the cost to operate or maintain something over time, which is higher if it’s not energy efficient.

Is there anything else people often overlook when considering the ramifications of losing Energy Star?

Energy efficiency is important for all constituencies and all sectors of the U.S. economy. Some folks will be harder hit by this, and by that, I mean low-income housing, schools, hospitals, and public sector buildings. Those facilities often have very limited budgets, so energy efficiency is one of the lowest-cost, most effective investments with good returns. But if you’re a low-income family, think about it: If you make less than $33,000 a year for a family of four, your utility bills have an outsized impact on the total cost of living. If the total utility bill is $300 or $400 a month, then utilities represent 10% to 15% of your total income, so efficiency can have an outsized impact.

The other side of that is mission-critical facilities. Having the ability to run lights, air conditioning, and cooling is important for comfort, but in some facilities — like precision manufacturing or biopharmaceuticals, data centers, things of that nature — it becomes a mission-critical area, not a nice-to-have. We can help reduce the amount of energy used by those facilities, extend their useful life, help them maintain their systems longer, and allow those businesses to be more competitive.

What’s your read on how the proposed Energy Star elimination is being discussed right now?

There’s a lot of hyperbole about Energy Star being eliminated — it’s a fait accompli. It is important to note that Energy Star is a line item identified in the statute by Congress for approval for funding. It seems pretty unrealistic, from a judicial standpoint, that it would be able to be eliminated before the end of this fiscal year.

I know that there are many, many representatives, both Republican and Democrats, who support Energy Star. We’ve had 35 years of bipartisan support, and it has been earmarked in congressional law many times, through multiple George H.W. and George W. Bush administrations. And there are a lot of lobbying efforts that I’m personally aware of within the commercial real estate industry and the manufacturing industry, where folks are reaching out and doing calls to action for the House and Senate Appropriations majority members — similar activities to what we did eight years ago when Energy Star was directly under fire.

It seems like such a strange thing for the administration to go after. It’s not like appliance manufacturers were clamoring for this, right?

It’s very vexing to me. I don’t get it. If the Trump administration wants to focus on affordability in American households, energy efficiency isn’t the thing to cut. I’m not sure if it’s getting caught up in the fact that it is in the Office of Atmospheric Pollution Prevention, or because at the Department of Energy’s Better Buildings Program, Biden launched the Better Climate Challenge. I don’t know if it’s because it had some ties to climate, but what’s ironic is that it didn’t start as a climate program. It began as an energy efficiency program, and it’s always been focused on businesses and the financial returns on investment — it helps us attract capital and debt for investment in real estate. It’s really disconnected.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Current conditions: More than a foot of snow is blanketing the California mountains • With thousands already displaced by flooding, Papua New Guinea is facing more days of thunderstorms ahead • It’s snowing in Ulaanbaatar today, and temperatures in the Mongolian capital will plunge from 31 degrees Fahrenheit to as low as 2 degrees by Sunday.

We all know the truisms of market logic 101. Precious metals surge when political volatility threatens economic instability. Gun stocks pop when a mass shooting stirs calls for firearm restrictions. And — as anyone who’s been paying attention to the world over the past year knows — oil prices spike when war with Iran looks imminent. Sure enough, the price of crude hit a six-month high Wednesday before inching upward still on Thursday after President Donald Trump publicly gave Tehran 10 to 15 days to agree to a peace deal or face “bad things.” Despite the largest U.S. troop buildup in the Middle East since 2003, the American military action won’t feature a ground invasion, said Gregory Brew, the Eurasia Group analyst who tracks Iran and energy issues. “It will be air strikes, possibly commando raids,” he wrote Thursday in a series of posts on X. Comparisons to Iraq “miss the mark,” he said, because whatever Trump does will likely wrap up in days. The bigger issue is that the conflict likely won’t resolve any of the issues that make Iran such a flashpoint. “There will be no deal, the regime will still be there, the missile and nuclear programs will remain and will be slowly rebuilt,” Brew wrote. “In six months, we could be back in the same situation.”

California, Colorado, and Washington led 10 other states in suing the Trump administration this week over the Department of Energy’s termination of billions in federal funding for clean energy and infrastructure projects. In a lawsuit filed in federal court in San Francisco, the states accuse the agency of using a “nebulous and opaque” review process to justify slashing billions in funding that was already awarded. “These aren’t optional programs — these are investments approved by bipartisan majorities in Congress,” California Attorney General Rob Bonta said at a press conference announcing the lawsuit, according to Courthouse News Service. “The president doesn’t get to cancel them simply because he disagrees with them. California won’t allow President Trump and his administration to play politics with our economy, our energy grid and our jobs.”

Get Heatmap AM directly in your inbox every morning:

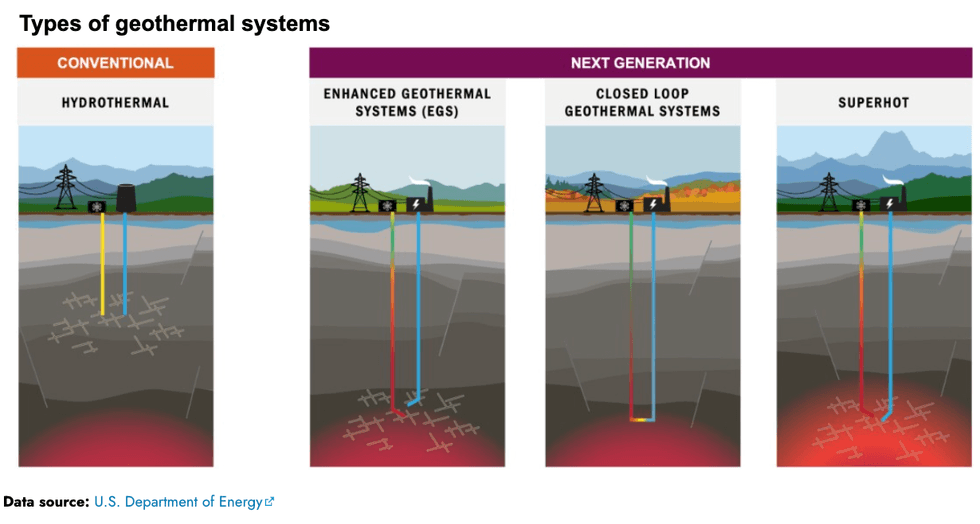

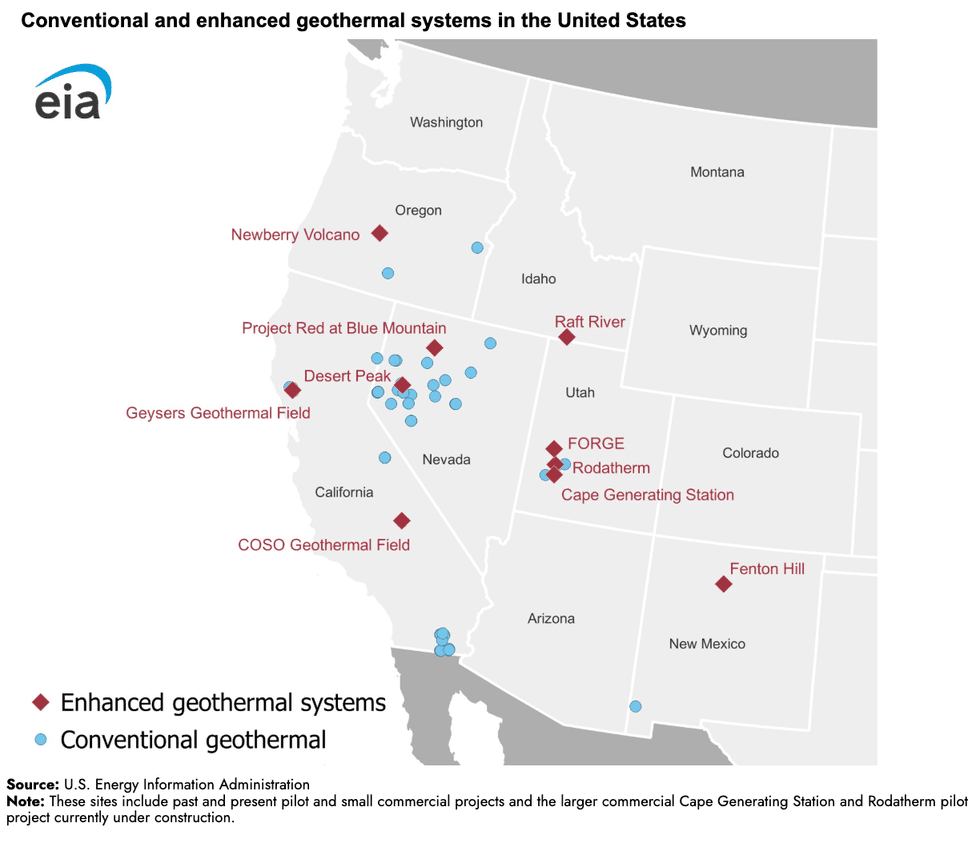

If you’re looking for a sign of the coming geothermal energy boom in the U.S., consider this: There is now a double-digit number of next-generation projects underway, according to an overview the Energy Information Administration published Thursday. For the past century, geothermal energy has relied upon finding and tapping into suitably hot underground reservoirs of water. But a new generation of “enhanced” geothermal companies is using modern drilling techniques to harness heat from dry rocks.

If you’re looking for a thorough overview of the technology, Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote the definitive 101 explainer here. But a few represent some of the earliest experiments in enhanced geothermal, including the Fenton Hill in New Mexico, established in the 1970s, which was the world’s first successful project to use the technology.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

When Exxon Mobil announced plans in December to scale back its spending on low-carbon investments, the oil giant justified the move in part on all the carbon capture and storage projects poised to come online this year that would vault the company ahead of its rivals. This week, Exxon Mobil started transporting and storing captured carbon dioxide at its latest facility in Louisiana. The New Generation Gas Gathering facility on the western edge of the state’s Gulf Coast is the company’s second CCS project in Louisiana. Known as NG3, the project is set to remove 1.2 million tons of CO2 per year from gas streams headed to export markets on the coast. The Carbon Herald reported that two additional CCS projects are set to start up operations this year.

CCS got a big boost in October when Google agreed to back construction of a gas-fired power plant built with carbon capture tech from the ground up. The plant, which Matthew noted at the time would be the first of its kind at a commercial scale, is sited near a well where captured carbon can be injected. Senate Democrats, meanwhile, are reportedly probing the Trump administration’s decision to redirect CCS funding to coal plants.

In 2019, Maine expanded its Net Energy Billing program to subsidize construction of commercial-scale solar farms across the state. “And it worked,” Maine Public Radio reported last July when the state passed a law to phase out the funding, “too well, some argue.” In 2025 alone, ratepayers in the state were on the hook for $234 million to support the program. Solar companies sued, arguing that the abrupt cut to state support had unfairly deprived them of funding. But this week U.S. District Judge Stacey Neumann denied a motion the owners of dozens of solar farms filed requesting an injunction.

That isn’t to say things aren’t looking sunny for solar in Maine. On the contrary, just yesterday the developer Swift Current Energy secured $248 million in project financing for a 122-megawatt solar farm and the Poland Spring water company went on statewide TV to show off the new panels on its bottling plant. The federal outlook isn’t as bright at the moment. As Heatmap’s Jael Holzman reported in December, the solar industry was begging Congress for help to end the Trump administration’s permitting blockade on new projects on federal lands.

The Trump-stumping country music star John Rich is continuing his crusade against the Tennessee Valley Authority. Months after blocking construction of a gas plant in his neighborhood, Rich personally pressed TVA CEO Don Moul to reroute a transmission line, posting a video Thursday of farmers who opposed the federal utility’s use of the right of way process to push through the project. Rich said Moul “personally told me as of this morning” TVA will put the effort on hold. The left-wing energy writer and Heatmap contributor Fred Stafford summed it up this way on X: “MAGA NIMBY rises, Dark Abundance falls. TVA ratepayers will be paying more for a rerouted transmission project because this country music star threw his support behind a local farmer who refuses to allow the transmission line to cross his land.”

Rob talks about the consumer response to fuel economy with Yale’s Kenneth Gillingham, then gets the latest Clean Investment Monitor data from Rhodium Group’s Hannah Hess.

It hasn't attracted as much attention as you might expect, but President Donald Trump has essentially killed all fuel economy rules on cars and trucks in the United States.

By the end of the year, automakers will face virtually no limits on how many huge gas guzzlers they can sell to the public — or what those purchases will do to domestic oil prices. But is the thinking driving this change up to date?

On this episode of Shift Key, Rob is joined by Kenneth Gillingham, a professor of environmental and energy economics at Yale. They chat about how the economics profession changed its mind about fuel efficiency rules for cars and trucks — and then recently changed its mind again. They also debrief about what the Trump rollback gets right and wrong in its key economic assumptions and how that might affect its reception.

Then Rob chats with Hannah Hess, an associate director from the Rhodium Group about new Clean Investment Monitor data that shows the U.S. clean energy economy was a “tale of two industries” in Q4 2025.

Shift Key is hosted by Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Here is an excerpt from their conversation:

Robinson Meyer: Let’s just roll the clock back to 2015 or 2016. At that point, the Obama-era standards had been in effect for some time. Where was the field of economics thinking about the efficiency gains from efficiency-based regulation in cars?

Kenneth Gillingham: That’s a great question. A series of papers came out in the early 2010s, either as working papers initially, and then they were published in those subsequent years. So if you were asking even me around 2015, I would have said, well, it does appear that consumers do value a lot of the future fuel savings and perhaps nearly all of the future fuel savings. If that is the case, that pulls out one of the key motivations for fuel economy standards or vehicle greenhouse gas standards that save fuel: It makes it harder for those standards to look to have positive net benefits.

Meyer: And I should say that neither the CAFE standards, which are from the Department of Transportation and regulate fuel mileage, nor the EPA greenhouse gas standards, which regulate the number of the amount of tons of carbon that come out of the car, like the truck tailpipe — they’re not cost free, right? They cost — I mean, at least as of the time of the first Trump administration — they cost like, they added to the cost of vehicles by about a thousand dollars or $1,200 dollars a vehicle on average. Now, consumers saved that over the life of the vehicle many times over. But if consumers are already taking into account those efficiency gains, then that tradeoff that the rules kind of forced consumers in maybe weren’t worth it.

Before we move on to where we are now, just staying in this 2015 zone, how did the literature reach this conclusion? What methodology were economists using to say, actually, consumers take all the fuel savings into account when they make a purchasing decision?

Gillingham: It’s a great question. So conceptually, they were looking at prices and quantities of vehicles. And they were looking at cases where you had, for some reason, the efficiency was improved, so there was some way, some exogenous way that efficiency was improved. And then looking at how the prices on the market re-equilibrated. And in particular, this was used for used cars. So much of the early 2010 literature that we’re talking about here brings in used cars and new cars. But importantly, it is including used cars and looking at how used car prices change with efficiency changes. Some of the literature was new cars as well, but they were generally finding relatively high valuation ratios.

Meyer: Give us an example. Is this like consumers, when they were buying a Prius, took into account all the fuel savings from that Prius as compared to like, say, a Toyota Tacoma, like the Prius price included this premium for fuel efficiency?

Gillingham: That’s exactly right.

You can find a full transcript of the episode here.

Mentioned:

From Heatmap: Trump’s One Big Beautiful Blow to the EV Supply Chain

Clean Investment Monitor’s U.S. Q4 2025 Update

This episode of Shift Key is sponsored by ...

Accelerate your clean energy career with Yale’s online certificate programs. Explore the 10-month Financing and Deploying Clean Energy program or the 5-month Clean and Equitable Energy Development program. Use referral code HeatMap26 and get your application in by the priority deadline for $500 off tuition to one of Yale’s online certificate programs in clean energy. Learn more at cbey.yale.edu/online-learning-opportunities.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.

This transcript has been automatically generated.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Robinson Meyer:

[1:25] It is Friday, February 20. The Trump administration made two big changes at the Environmental Protection Agency last week. The first, which we talked about last show, was that it revoked the endangerment finding, which is the key legal document that allows the EPA to regulate carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. The second is that it revoked what are sometimes called the clean car rules. These are the EPA’s greenhouse gas rules for cars and light-duty trucks. Now, this second change was a big deal, and in some ways, I think a bigger deal than maybe the amount of attention that it got. Because it’s part of a multi-front war on fuel efficiency standards from the Trump administration. It maybe hasn’t gotten a lot of attention, but by the end of this year, the U.S. Will probably not regulate fuel mileage or vehicle efficiency in any way. We’ll essentially be back to the days of the early George W. Bush administration, when automakers could sell as many Hummers as they wanted. Now, the repeal effort legally from Trump relies on a number of economic arguments. The most important of these is the EPA’s argument that it will save the public more money than it costs to roll these rolls back. The EPA says we’ll get about $1.3 trillion worth of benefits from this rollback. Now some of the assumptions behind this finding are contested and some are ideological. Some are, I think, wrong.

Robinson Meyer:

[2:41] Some are just outdated. So today, I wanted to talk to an economist about one of the most important claims in the Trump repeal and why it is no longer in touch with the economics literature.

Robinson Meyer:

[2:51] We’ll also chat about the broader set of economic arguments the Trump administration is making. Our guest today is Ken Gillingham. He’s a professor of economics at Yale and a former senior economist for energy and the environment at the White House Council of Economic Advisors. My conversation with him is coming up. And then in the back half of the show, I talked to Hannah Hess, an associate director at the Rhodium Group about new data on how clean energy investment in the United States held up through the end of last year, and why it’s kind of a tale of two industries in America right now. The clean electricity sector is booming, while the electric vehicle supply chain is falling apart. So in this episode, it’s all about cars and EVs and how we regulate them in the US, call it our Car Talk episode, and it’s all coming up today on Shift Key.

Robinson Meyer:

[3:38] Ken Gillingham, welcome to Shift Key.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[3:41] Pleasure to speak with you, Robinson.

Robinson Meyer:

[3:43] So the Trump administration comes out with its big greenhouse gas endangerment finding repeal last week. It’s kind of like a two-part document, as we talked about in the past episode. So on the one hand, it’s an argument that the EPA should not regulate greenhouse gases as dangerous pollutants. But then the second part of it is, an argument basically entirely about tailpipe greenhouse gas standards about whether the epa should be regulating greenhouse gases that come out of cars and trucks and the epa argues as you might expect that it shouldn’t i will say that the second Trump administration just like the first Trump administration has to put out a fairly lengthy analysis of why it has reached this conclusion and even though the president during his press briefing announcing this change called global warming, a giant scam. That fact does not feature in their analysis. They take a different approach. They also, as they did in the first Trump administration, actually cite your work all across the analysis. They love to cite your work on the greenhouse gas standards. So can you just give us a sense of like, what did you think about the analysis that you’ve seen from the Trump administration and their legal justification for rolling back the vehicle rules so far.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[4:59] Right. It was a very simplistic analysis in many respects. They simply took the 2024 analysis that was done under the Biden administration, EPA, and they made a set of tweaks. These tweaks happen to have enormous ramifications. The biggest one, of course, is removing the endangerment finding and eliminating greenhouse gases. That is an enormous one. But there are other tweaks that they made. They changed the expected future gasoline price. They changed how they value future fuel savings when people buy a more efficient car.

Robinson Meyer:

[5:39] Can you walk us through a little bit more? So what are the most important of the tweaks that they made? And kind of what message are they trying to send with those tweaks?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[5:49] Well, one message they’re sending is that greenhouse gases don’t matter, other air pollutants don’t matter, and that’s an obvious message. This has been talked about a lot. The other message they’re sending is that consumers, when they’re buying a car, make a decision and fully value the future fuel savings. When you make that assumption, you’re basically saying that consumers fully value the future fuel savings. And because they’re already incorporating the benefit in their decision, they get no benefit from a rule that nudges them into a more efficient car. Those both are pivotal. Either of those two would change the net benefits of the rule. And they’re both huge, many, many millions of dollars, trillions of dollars.

Robinson Meyer:

[6:38] When I started out as an environmental reporter, there was this idea about energy efficiency rules. And I think especially efficiency rules around cars and trucks, which to be clear about what a greenhouse gas standard is when you’re talking about cars and trucks, it really just is a type of energy efficiency rule. And the idea that I heard from researchers, from economists, is that you need some kind of efficiency regulation because this is a market failure, because consumers don’t take into account all the literal monetary benefits they’re going to get from buying a more efficient an appliance or a more efficient car when they make the purchase. It just doesn’t factor into their calculus. And so you need the government to kind of push appliance makers or push car makers toward more efficient products, because otherwise, not only are you going to have consumers maybe not fully maximizing their welfare, so to speak, by buying, you know.

Robinson Meyer:

[7:32] More gas guzzling cars than they should, but also like as a country, you’re going to consume much more gas. And that means that gas prices are going to be higher. And that means even people who make more efficient vehicle purchases are going

Robinson Meyer:

[7:44] to have to pay more for gas, right? It’s this big systematic problem. What I was not aware of is that the economics literature about that finding and that idea has kind of shifted under our feet a few times over the past decade. And that while that might have been the state of the art in 2008, it had kind of changed by the middle of last decade. and now it might have changed again. So can you just update us on like, First of all, was my summary correct? And second, then, like, how did economists change their mind?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[8:24] Yes, your summary is spot on. It’s been long understood that when regular people, anyone goes to a store, consumers go to a store and buy a more efficient appliance or buy a more efficient car, that they appear to value only to some degree the future fuel savings or energy bill savings they would get from the more efficient appliance or more efficient car. This is often called the energy efficiency gap. People have written on it for years. In the car context, there’s a longstanding understanding in the industry, as well as from National Academy’s reports and other sources, that consumers value roughly 2.5 to 3 years, somewhere in that ballpark, of future fuel savings when they purchase a car. Why don’t they value the rest? Well, people usually attribute it to some behavioral feature of the way we make decisions. Which often people use the word inattention. So for example, they might be inattentive to those future fuel savings and really be focusing on just a few attributes of the cars.

Robinson Meyer:

[9:34] We kind of assume that consumers, they buy a new car for a decade or for 12 years. I think the average car on the road now is something like 13 years old. But when they buy the car, as you were saying, they’re only thinking of that first three and a half years. And so all the fuel savings from the back seven or the back nine, just don’t factor into their kind of internal vehicle purchasing function at all.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[9:59] That’s right. And that’s how people had thought about it, that people really paying attention to the first two and a half or three years, and ignoring the remaining nine or so years in that life of the car. And that provides a motivation for policy. If you truly have people who don’t value those future fuel savings, they’re certainly going to value it when they go to the pump and fill up their car with gasoline. There’s no question about that. Everyone agrees that they value it at the time that they’re actually filling up their car with gasoline, but they might not have valued it when they were making that car purchase. That’s kind of fundamentally a strong and longstanding motivation for fuel economy standards. So it may not be surprising that the Trump administration, in trying to rescind the standards, attacked that head on and tried to effectively roll that assumption back as well as rolling back the environmental greenhouse gas engagement finding.

Robinson Meyer:

[10:49] This has changed a little bit. So back maybe around the time of the first Trump administration, the economic literature had shifted somewhat on this question. So, Let’s just roll the clock back to 2015 or 2016. At that point, the Obama era standards had been in effect for some time. Where was the field of economics thinking about the efficiency gains from efficiency-based regulation in cars?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[11:18] That’s a great question. A series of papers came out in the early 2010s, either as working papers initially, and then they were published in those subsequent years. So if you were asking even me around 2015, I would have said, well, it does appear that consumers do value a lot of the future fuel savings and perhaps nearly all of the future fuel savings. If that is the case, that pulls out one of the key motivations for fuel economy standards or vehicle greenhouse gas standards that save fuel. It makes it harder for those standards to look to have positive net benefits.

Robinson Meyer:

[11:52] And I should say that neither the CAFE standards, which are come from the Department of Transportation and regulate fuel mileage, nor the EPA greenhouse gas standards, which regulate the number of the amount of tons of carbon that come out of the car, like the truck tailpipe. They’re not cost free, right? They cost. I mean, at least as of the time of the first Trump administration, they cost like they added to the cost of vehicles by about a thousand dollars or twelve hundred dollars a vehicle on average. Now, consumers saved that over the life of the vehicle many times over. But if consumers are already taking into account those efficiency gains, then that trade-off that the rules kind of forced consumers in maybe weren’t worth it. Before we move on to where we are now, just staying in this 2015 zone …

Robinson Meyer:

[12:39] How did the literature reach this conclusion? What methodology were economists using to say, actually, consumers take all the fuel savings into account when they make a purchasing decision?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[12:49] It’s a great question. So conceptually, they were looking at prices and quantities of vehicles. And they were looking at cases where you had, for some reason, the efficiency was improved. So there was some way, some exogenous way that efficiency was improved. And then looking at how the prices on the market re-equilibrated. And in particular, this was used for used cars. So much of the early 2010 literature that we’re talking about here brings in used cars and new cars. But importantly, it is including used cars and looking at how used car prices change with efficiency changes. Some of the literature was new cars as well, but they were generally finding relatively high valuation ratios.

Robinson Meyer:

[13:34] Give us an example. Is this like consumers, when they were buying a Prius, took into account all the fuel savings from that Prius as compared to like, say, a Toyota Tacoma, like the Prius price included this premium for fuel efficiency?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[13:50] That’s exactly right. Conceptually, you could see it as in the Prius context, the price of the Prius incorporated all of those future fuel savings over the expected life of the vehicle.

Robinson Meyer:

[14:02] That is interesting, because it is true that when you look on Carvana or something, or you look at the cars.com app, two places that I have spent some amount of time in my life, you do see that Prius, used Prius prices are like much higher than sedans of similar size. I mean, it’s a Toyota too, so it gets a kind of premium in the used market anyway. But there is some kind of premium that people assign to cars that get better fuel mileage. So do economists still think this? like do you think the consumers take into account all of those fuel savings when they buy a new car not.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[14:35] All of those fuel savings so I think your questions are a really great one it’s consumers definitely value to some degree future fuel savings. There’s no question about that. Everyone sees it. You can see it in the Prius, although it is a Toyota that does higher retail values, but you can see it across the board. The question is how much of those future fuel savings? You can go back to the original literature that said 2.5 years or three years. That would indicate that there’s a substantial undervaluation of the future fuel savings you could get over the life of the vehicle.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[15:06] More recent evidence has started to come to the conclusion that the previous evidence, that 2.5 or 3 years, was much closer to being correct than the early 2010 articles. And there are two reasons for this. One reason for this is that the newer articles are using updated empirical designs, more careful statistical approaches. I want to emphasize, it’s not easy to estimate this parameter. There are a lot of other variables that influence how people make decisions about cars in terms of all the other attributes of the vehicles, but also the brand, the timing, the gasoline price, all of these things matter.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[15:51] Expectations about gasoline prices matter. This is a very difficult parameter to estimate. So there have been, I would say, improvements in the empirical design of recent studies that I think have helped. That’s the first one. The second reason why we generally are seeing different estimates is that people are being a little bit more careful about whether they take the average of a ratio or the ratio of averages. It’s a subtle point and seems quite minor. Fundamentally, the valuation of those future fuel savings is a ratio. We’re talking about, do they value 50%? Do they value 90%? Do they value 100%? That is a ratio in the sense of the amount that they value over the total amount of future fuel savings.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[16:43] That needs to be handled very carefully in empirical designs. When you correct for that, some of the old studies had to have no problem, but some of them did have some problems. When you correct for that, you actually end up getting similar numbers in some of the previous studies to what we’re finding in the newer studies.

Robinson Meyer:

[17:03] Yeah, basically, we’ve swung all the way back. So literally, there was a mathematical error in some of these studies and how they calculated the percentage of how much people valued the fuel savings. And if you correct for that error, then you swing right back to where the literature used to be.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[17:20] I’m not going to say negative things about my fantastic co-authors and friends, but that’s how science evolves. That’s how we continue learning.

Robinson Meyer:

[17:29] What kind of assumptions did the Trump administration make about fuel prices in its proposal? I mean, does it think that fuel prices are going to get more expensive? Because part of the whole calculus of these rules is that basically, yeah, people like saving fuel when oil is cheap, but they really like saving fuel when oil is expensive. Do they include some predictions about whether gas is going to get more or less expensive in their rulemaking?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[17:56] Well, in the proposed rule for the EPA vehicle greenhouse gas standards, they made one of the assumptions that is one of my favorite assumptions in the entire rule. They arbitrarily said, because there’s an energy dominance agenda, that fuel prices were going to be much, much lower, and thus the benefits from future fuel savings were going to be much, much lower. To their credit, that was entirely unjustified, would never hold up in court, and they removed it in the final rule. In the final rule, they’re using within reason, but very low fuel price, alternative fuel baseline from the Energy Information Administration. And so they still are using a lower number than one might argue, but it’s no longer quite as egregious as it was in the proposed rule.

Robinson Meyer:

[18:40] You had a relatively important paper on the CAFE standards a few years ago at this point and about how the fuel efficiency standards kind of interrelated with the used car market that I continue to think is this really interesting finding that kind of maybe helps people understand why fuel economy is a tough thing to regulate, a very important thing to regulate, but still has these tough follow on effects you might not predict. Can you just describe it to us for a second?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[19:06] So about 10 years ago, Hyundai and Kia stated that their fuel economy was much higher than it actually was. And then suddenly, on one day, they restated their fuel economy. We had transaction price data and we could immediately see how transaction prices for those cars that had their fuel economy restated changed relative to prior, as well as relative to other vehicles in Hyundai and Kia, as well as other similar models by other automakers that did not see this change. In their stated fuel economy.

Robinson Meyer:

[19:38] And what do you find?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[19:40] We found that consumers undervalue fuel economy. It’s actually not too far from the, it’s right in line with the two and a half to three year payback period. So about a 23% or 30% undervaluation. So people value about 23% to 30% of future fuel savings, which means that there’s still 70% to 77% that they don’t value.

Robinson Meyer:

[20:04] There’s a few different things that have happened in the fuel economy rules lately, and I think it’s actually worth putting them all together. So, you know, the US regulates the efficiency of its internal combustion vehicles in two ways. Basically, we had the EPA greenhouse gas standards, those regulated greenhouse gases coming out of tailpipes. But then we also had this much older set of standards from the Department of Transportation called the CAFE standards, which regulate the collective fuel economy of new vehicles. And I think what people may not have realized is that the Trump administration has basically effectively eliminated both of these programs. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act reduced the penalties for the CAFE standard, the Department of Transportation, the older standard to zero. So automakers will not be fined for violating the CAFE standards on the one hand. On the other hand, the EPA is now in the process of trying to repeal not only the greenhouse gas standards for vehicles, but in fact, the idea that it should regulate greenhouse gases altogether. Is there any precedent for the US not having fuel economy or engine efficiency or gas mileage standards of any kind in the historical record? And like, what could we predict will happen from the fact that the US will now no longer have standards of this kind, at least for the next few years?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[21:28] So you’re completely correct that as of now, we effectively do not have standard or as of the finalizing of the CAFE rule, I should really say, because there are two pieces here. Congress and their one big, beautiful bill eliminated the penalties for violating the CAFE standard, which is Corporate Average Fuel Economy standard. In addition, they came out in December with a proposed rule, which made the increase in the standard so minimal that it’s effectively non-binding. So there is actually an increase in the standard. Legally, I think they felt they had to do that. But it’s basically a minimal increase. So there will be non-binding. By non-binding, I just mean they’re ineffective. They’re not doing anything.

Robinson Meyer:

[22:13] And crucially, that really kills the trading market, right? Right. Because the way that EV companies like Tesla, but now like Rivian and Lucid, too, made a good deal of their regulatory income. And for Tesla, some key early profits was by selling credits from their cars, like regulatory credits from their cars to GM, to Nissan, to these producers of these big gas guzzling cars. So they’ve killed a key revenue driver for the all electric automakers as well.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[22:42] That’s right. The proposed rule eliminates something that economists have been pushing for, which is to allow for trading. That came about from Republican economists actually were the ones who made that happen initially. And the trading lowers the costs of compliance. And so they eliminated it, which also is a shot below the bow for all of the EV companies because now they are no longer going to make money from this trading. So it’s an additional hit there. So you’re completely right that with the finalization of the CAFE rule, as expected, in the next few months, we’ll enter a phase with effectively no standards on cars. We have been there in the past. You can go back to before there were standards, before the oil crisis in the 1970s, and cars were very big and very inefficient. Cars are actually bigger today, but they were very inefficient, extremely inefficient. There also are periods, long periods, especially in the 80s, when standards stayed pretty flat. And here I’m talking about corporate average fuel economy standards before 2009, when the EPA vehicle greenhouse gas standard was implemented. So corporate average fuel economy standards, when they were flat, basically we didn’t see much improvement in fuel economy, minimal improvement in fuel economy for years on end.

Robinson Meyer:

[24:02] And did things get worse or they just kind of stayed flat?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[24:05] Stayed flat. They stayed flat. But there was a technology improvement during this time. Just all that technology improvement was poured into increasing horsepower, increasing acceleration, et cetera.

Robinson Meyer:

[24:18] I find this to be one of the most interesting conversations about the whole deal here, because people do look at these standards of the past 10 years and they say, look, cars have gotten bigger during that time. Horsepower has gone up. And because of that, we actually haven’t seen some of the efficiency gains that we once anticipated seeing at the moment the Obama standards were put into place. Basically, like the increasing size of vehicles mostly has kind of eaten into some of those gains. But it seems to me that like we see horsepower improvements and we see vehicles get bigger during periods of time when there are no standards and fuel economy does not improve. And so if we see horsepower improvements and we also see vehicles get bigger and fuel economy does improve, that suggests the fuel economy standards actually did work at least a little bit.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[25:06] It is all about what would have happened otherwise. And I think you’re hitting it on the nose here that we would have seen even potentially larger vehicles and even potentially less efficient vehicles had it not been for the standards. So I think that it’s simply false to say that the standards didn’t do anything because horsepower has gotten larger, because cars have gotten heavier, which is true. Cars have gotten heavier. Horsepower has increased. A lot of it is a switch to SUVs and light trucks and crossovers. That is an ongoing shift. But that would have happened anyway. There are features of the design of standards that may lead to, if you have a lighter standard or more relaxed standard for certain types of vehicles, such as SUVs and light trucks, that provides an incentive to sell SUVs and light trucks. That design feature may have enhanced the upscaling, but the automakers make

Kenneth Gillingham:

[26:03] more money on the big vehicles. They were going to upscale anyway.

Robinson Meyer:

[26:06] Here’s the last question, which is when you look at the assumptions in the rulemaking, when you look at the errors, you know, the agencies have to do this cost benefit analysis when they make a rule change. And without getting too into the weeds, the agency has to prove to the courts, to the American people, that when it changes a regulation, either strengthening a regulation or weakening a regulation is the Trump administration is doing here, that the benefits of that change exceed the costs.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[26:33] Can I just interrupt there? There is a possibility that you can have a net negative benefit policy. You just need to justify it from other legal pathways. Historically, in the courts, it has been very difficult to win a court case when net benefits are negative.

Robinson Meyer:

[26:48] So perfect entree then. When you look at the assumptions made by the Trump administration in their cost benefit analysis, do you believe that if they were updated to reflect more accurate assumptions that the benefits would still exceed the cost of the rule?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[27:03] Oh, far from it. The benefits would be very negative. In fact, even in some of their own scenarios, the net benefits are negative. So it’s pretty clear that the net benefits would not be positive from this rule. I’m sure they know this. The decision to rescind the rules was made before the analysis and the analysis had to follow.

Robinson Meyer:

[27:23] Well, as the legal fight over these rules keeps developing and the economic discussion of the assumptions made in the legal documents. We will keep in touch with you. Ken Gillingham, thank you so much for joining us on Shift Key.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[27:35] It’s a pleasure. Thank you.

Robinson Meyer:

[29:13] And joining us now is Hannah Hess. She’s an associate director at the Rhodium Group. Hannah, welcome to Shift Key.

Hannah Hess:

[29:19] Thank you so much. I’m excited to be here.

Robinson Meyer:

[29:21] So every quarter, the Clean Investment Monitor, which is a project of the Rhodium Group and MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research, has published this summary of all the investment that happened across the clean energy economy over the past quarter, which means that at this point, it’s a pretty good data source and give us a guide to what’s been happening in the clean energy economy since the Inflation Reduction Act era, or at least since the IRA era began. The Q4 2025 report just came out. Can you give us the top line of what it found?

Hannah Hess:

[29:55] Sure. So we’ve been tracking clean investment since about a year after the IRA passed, but our baseline of data goes all the way back to the first quarter of 2018. We find that in Q4, clean investment softened a little bit after a record high Q3 2025 that was largely driven by people purchasing EVs. When we zoom out and look at the full year 2025, we find that it was a record year for clean investment, up 5% from 2024.

Robinson Meyer:

[30:31] So Q3, huge quarter driven by EV purchases, and that’s probably driven especially by the expiring of the IRA demand side tax credits for EV purchasing. Q4, a little soft. One thing I saw in the report was that Q4 2025 is like the first quarter really in the data set that was softer than the quarter a year earlier, right?

Hannah Hess:

[30:56] Yeah. So Q4 is the first instance in our tracking of negative quarter on year growth and clean investment. So since the beginning of this data set, every time we look back at the level observed in the same time period the previous year, it would be an increase even when there was some fluctuation from quarter-on-quarter. And so that would tell us overall this segment is still strong and it’s a good sign that clean investment continues to expand. But that trend ended in Q4 2025 when investment declined 11% from the level that was observed in the last quarter of 2024. New project announcements also softened. So in addition to tracking how much investment is occurring in the construction of new facilities and in those consumer purchases of clean technologies like EVs, heat pumps, rooftop solar, we’re also looking at what developers are doing, how much new projects they’re announcing each quarter. New announced manufacturing projects totaled $3 billion in Q4 2025, which was down 48% both from the previous quarter and year-on-year, and that $3 billion of new manufacturing projects is the lowest quarterly level since Q4 2020.

Hannah Hess:

[32:18] Looking at the full year, announcements for new manufacturing projects were down 26% compared to 2024. So all of these are just signs that the manufacturing segment, which is largely driven by the EV supply chain, is weakening.

Robinson Meyer:

[32:36] I want to talk more about that, but can you zoom out for a second and just tell us what is encompassed by the term clean investment? What sectors are we talking about and what sectors maybe are we not talking about here?

Hannah Hess:

[32:49] So the Clean Investment Monitor tracks investment in three segments of the economy. That’s clean tech manufacturing. So within the EV supply chain, it’s batteries, it’s vehicle assembly, it’s critical minerals processing projects. We also track the manufacturing of solar components, wind components, and electrolyzers for hydrogen. We have a second segment that’s energy and industry, and that lumps together clean electricity, solar, storage, wind, as well as industrial decarbonization projects, which is a much smaller segment. That’s investments in clean products like clean cement and clean steel, as well as sustainable aviation fuels and hydrogen production. And then the final segment of clean investment, we call retail, and that’s small businesses and household purchases of clean technologies that’s, for the most part, EVs and also heat pumps and distributed solar. The thing weaving all of these technologies together is that they were all incentivized by the Inflation Reduction Act. But broadly, we just say investments in the manufacture and deployment of emissions reducing technologies.

Robinson Meyer:

[34:04] What drove the decline in investment last quarter? And a decline not only in real investment, but in investment momentum and the number of announcements people are making. What drove that?

Hannah Hess:

[34:15] So EV purchasing fell off a cliff compared to Q3 2025. And because those retail segment purchases, just like the overall US economy, consumer spending drives most of the clean investment. That was a big dip. But what I view as a more concerning trend is this is the fifth consecutive quarter of decline in clean manufacturing investment. And announcements of new manufacturing projects were exceeded by cancellations of new manufacturing projects. So that’s the pipeline shrinking. And that is concerning for not only what’s happening in Q4, but when we look out for the next couple of years, what is the clean tech manufacturing supply chain look like? What is the U.S. workforce for clean tech manufacturing look like? Lots to unpack there.

Robinson Meyer:

[35:12] The Detroit-based automakers, Ford GM and Stellantis, announced a $50 billion charge combined on their EV investments over the past few months. And we’ve seen a number of them announce that their big flagship projects, like Blue Oval City from Ford in Tennessee, are going to be reoriented from building EVs and batteries to building large internal combustion vehicle trucks. In the data, does it seem like these big by the largest kind of final assembly automakers are driving the bulk of these cancellations? Are you seeing weakness like down further in the supply chain where it’s these individual, you know, parts makers or component makers who make up the actual bulk of the industrial economy who are now experiencing trouble? It’s not just these big, you know, charismatic firms at the top.

Hannah Hess:

[36:13] When I look at all of the cancellations that occurred in cleantech manufacturing in 2025, ranked from the highest value to the lowest value. Top three, General Motors, Stellantis, Ford. But then we see Gotion, FREYR Battery, Core Power, some smaller battery manufacturing projects that while they’re not at the three or four billion level, they really do add up to this record high cancellations that we saw in 2025. I think an important way to contextualize the cancellations also is just to

Hannah Hess:

[36:53] say that when we zoom out, 97% of all the canceled investment in 2025 was in the EV supply chain. That’s a total of $22 billion of canceled projects. And that exceeded the $21 billion of announced projects. So this is really a broader story, I think, than just those big three automakers.

Robinson Meyer:

[37:15] So that’s the bad news. Was there any good news in the data from last quarter?

Hannah Hess:

[37:21] I would love to share a little bit of good news. And that is that clean electricity is holding up better than manufacturing. Solar and storage are really the workhorses when it comes to clean investment. One thing I think is important when you look at this story is to note that the pullback that we’re seeing in clean investment isn’t across the board. Investment in clean electricity was $101 billion over the course of 2025, and that’s up 18% compared to the previous year. We lumped together clean electricity and industrial decarbonization, but clean electricity was 96% of that total. Also, I think it’s important to call out that while we saw $9 billion canceled in the last quarter, that was in a pool of $22 billion worth of new investment announcements. So the pipeline of clean electricity is continuing to grow. And I think that’s a really important story here.

Robinson Meyer:

[38:24] Yeah, it’s so, I mean, this is what we see at Heatmap too. You know, investment in EVs, at least in the near term, has really collapsed. I mean, the EV story is just not what it was a few years ago. But the electricity story is popping off. It is crazy. I mean, it’s all about data centers, right? And it’s all about demand growth. At least that’s what we observed from our end. Maybe you’ve seen something different. but like the solar storage story is just enormous.

Hannah Hess:

[38:49] Truly, yeah. Solar and storage is the leading driver within energy and industry. In just the last quarter, we saw $18 billion worth of utility scale solar and storage installations, which was up about 10% from the same time last year.

Robinson Meyer:

[39:05] Cool. Well, thank you so much for joining us on Shift Key.

Hannah Hess:

[39:10] Thank you, Rob. It’s been really nice to talk.

Robinson Meyer:

[39:14] Shift Key is a production of Heatmap News. Our editors are Jillian Goodman and Nico Lauricella. Multimedia editing and audio engineering is by Jacob Lambert and by Nick Woodbury. Our music is by Adam Kromelow. See you next week.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.