You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

You’ve probably noticed — even Trump has noticed — but the reason why is as complicated as the grid itself.

You’re not imagining things: Electricity prices are surging.

Electricity rates, which have increased steadily since the pandemic, are now on a serious upward tear. Over the past 12 months, power prices have increased more than twice as fast as inflation, according to recent government data. They will likely keep rising in years to come as new data centers and factories connect to the power grid.

That surge is a major problem for the economy — and for President Trump. On the campaign trail, Trump vowed to cut Americans’ electricity bills in half within his first year in office. “Your electric bill — including cars, air conditioning, heating, everything, your total electric bill — will be 50% less. We’re going to cut it in half,” he said.

Now Trump has mysteriously stopped talking about that pledge, and on Tuesday he blamed renewables for rising electricity rates. Even Trump’s Secretary of Energy Chris Wright has acknowledged that costs are doing the opposite of what the president has promised.

Trump’s promise to cut electricity rates in half was always ridiculous. But while his administration is likely making the electricity crisis worse, the roots of our current power shock did not begin in January.

Why has electricity gotten so much more expensive over the past five years? The answer, despite what the president might say, isn’t renewables. It has far more to do with the part of the power grid you’re most familiar with: the poles and wires outside your window.

Before we begin, a warning: Electricity prices are weird.

In most of the U.S. economy, markets set prices for goods and services in response to supply and demand. But electricity prices emerge from a complicated mix of regulation, fuel costs, and wholesale auction. In general, electricity rates need to cover the costs of running the electricity system — and that turns out to be a complicated task.

You can split costs associated with the electricity system into three broad segments. The biggest and traditionally the most expensive part of the grid is generation — the power plants and the fuels needed to run them. The second category is transmission, which moves electricity across long distances and delivers it to local substations. The final category is distribution, the poles and wires that get electricity the “the last mile” to homes and businesses. (You can think of transmission as the highways for electricity and distribution as the local roads.)

In some states, especially those in the Southeast and Mountain West, monopoly electricity companies run the entire power grid — generation, transmission, and distribution. A quasi-judicial body of state officials regulates what this monopoly can do and what it can charge consumers. These monopoly utilities are supposed to make long-term decisions in partnership with these state commissions, and they must get their permission before they can raise electricity rates. But when fuel costs go up for their power plants — such as when natural gas or oil prices spike — they can often “pass through” those costs directly to consumers.

In other states, such as California or those in the Mid-Atlantic, electricity bills are split in two. The “generation” part of the bill is set through regulated electricity auctions that feature many different power plants and power companies. The market, in other words, sets generation costs. But the local power grid — the infrastructure that delivers electricity to customers — cannot be handled by a market, so it is managed by utilities that cover a particular service area. These local “transmission and distribution” utilities must get state regulators’ approval when they raise rates for their part of the bill.

The biggest driver of the power grid’s rising costs is … the power grid itself.

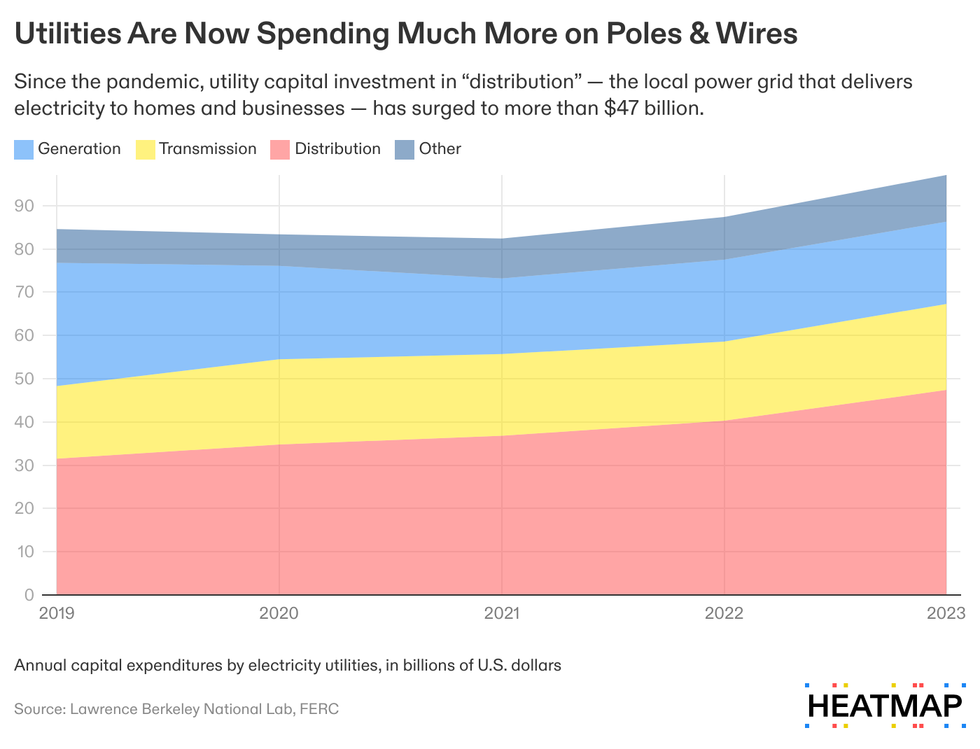

Historically, generation — building new power plants, and buying the fuel to run them — has driven the lion’s share of electricity rates. But since the pandemic, the cost of building the distribution system has ballooned.

Electricity costs are “now becoming a wires story and less of an electrons story,” Madalsa Singh, an economist at the University of California Santa Barbara, told me. In 2023, distribution made up nearly half of all utility spending, up from 37% in 2019, according to a recent Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory report.

Where are these higher costs coming from? When you look under the hood, the possibly surprising answer is: the poles and wires themselves. Utilities spent roughly $6 billion more on “overhead poles, towers, and conductors” in 2023 than in 2019, according to the Lawrence Berkeley report. Spending on underground power lines — which are especially important out West to avoid sparking a wildfire — increased by about $4 billion over the same period.

Spending on transformers also surged. Transformers, which connect different circuits on the grid and keep the flow of electricity constant, are a crucial piece of transmission and distribution infrastructure. But they’ve been in critically short supply more or less since the supply chain crunch of the pandemic. Utility spending on transformers has more than doubled since 2019, according to Wood Mackenzie.

At least some of the costs are hitting because the grid is just old, Singh said. As equipment reaches the end of its life, it needs to be upgraded and hardened. But it’s not completely clear why that spike in distribution costs is happening now as opposed to in the 2010s, when the grid was almost as old and in need of repair as it was now.

Some observers have argued that for-profit utilities are “goldplating” distribution infrastructure, spending more on poles and wires because they know that customers will ultimately foot the bill for them. But when Singh studied California power companies, she found that even government-run utilities — i.e. utilities without private investors to satisfy — are now spending more on distribution than they used to, too. Distribution costs, in other words, seem to be going up for everyone.

Sprawling suburbs in some states may be driving some of those costs, she added. In California, people have pushed farther out into semi-developed or rural land in order to find cheaper housing. Because investor-owned utilities have a legal obligation to get wires and electricity to everyone in their service area, these new and more distant housing developments might be more expensive to connect to the grid than older ones.

These higher costs will usually appear on the “transmission and distribution” part of your power bill — the “wires” part, if it is broken out. What’s interesting is that as a share of total utility investment, virtually all of the cost inflation is happening on the distribution side of that ledger. While transmission costs have fluctuated year to year, they have hovered around 20% of total utility investment since 2019, according to the Lawrence Berkeley Labs report.

Higher transmission spending might eventually bring down electricity rates because it could allow utilities to access cheaper power in neighboring service areas — or connect to distant solar or wind projects. (If renewables were driving up power prices as the president claims, you might see it here, in the “transmission” part of the bill.) But Charles Hua, the founder and executive director of the think tank PowerLines, said that even now, most utilities are building out their local grids, not connecting to power projects that are farther away.

The second biggest driver of higher electricity costs is disasters — natural and otherwise.

In California, ratepayers are now partially footing the bill for higher insurance costs associated with the risk of a grid-initiated wildfire, Sam Kozel, a researcher at E9 Insight, told me. Utilities also face higher costs whenever they rebuild the grid after a wildfire because they install sensors and software in their infrastructure that might help avoid the next blaze.

Similar stories are playing out elsewhere. Although the exact hazards vary region by region, some utilities and power grids have had to pay steep costs to rebuild from disasters or prevent the likelihood of the next one occurring.

In the Southeast, for instance, severe storms and hurricanes have knocked out huge swaths of the distribution grid, requiring emergency line crews to come in and rebuild. Those one-time, storm-induced costs then get recovered through higher utility rates over time.

Why have costs gone up so much this decade? Wildfires seem to grow faster now because of climate change — but wildfires in California are also primed to burn by a century of built-up fuel in forests. The increased disaster costs may also be partially the result of the bad luck of where storms happen to hit. Relatively few hurricanes made landfall in the U.S. during the 2010s — just 13, most of which happened in the second half of the decade. Eleven hurricanes have already come ashore in the 2020s.

Because fuel costs are broadly seen as outside a utility’s control, regulators generally give utilities more leeway to pass those costs directly through to customers. So when fuel prices go up, so do rates in many cases.

The most important fuel for the American power grid is natural gas, which produces more than 40% of American electricity. In 2022, surging demand and rising European imports caused American natural gas prices to increase more than 140%. But it can take time for a rise of that magnitude to work its way to consumers, and it can take even longer for electricity prices to come back down.

Although natural gas prices returned to pre-pandemic levels by 2023, utilities paid 30% more for fuel and energy that year than they did in 2019, according to Lawrence Berkeley National Lab. That’s because higher fuel costs do not immediately get processed in power bills.

The ultimate impact of these price shocks can be profound. North Carolina’s electricity rates rose from 2017 to 2024, for instance, largely because of natural gas price hikes, according to an Environmental Defense Fund analysis.

The final contributor to higher power costs is the one that has attracted the most worry in the mainstream press: There is already more demand for electricity than there used to be.

A cascade of new data centers coming onto the grid will use up any spare electron they can get. In some regions, such as the Mid-Atlantic’s PJM power grid, these new data centers are beginning to drive up costs by increasing power prices in the capacity market, an annual auction to lock in adequate supply for moments of peak demand. Data centers added $9.4 billion in costs last year, according to an independent market monitor.

Under PJM’s rules, it will take several years for these capacity auction prices to work their way completely into consumer prices — but the process has already started. Hua told me that the power bill for his one-bedroom apartment in Washington, D.C., has risen over the past year thanks largely to these coming demand shocks. (The Mid-Atlantic grid implemented a capacity-auction price cap this year to try to limit future spikes.)

Across the country, wherever data centers have been hooked up to the grid but have not supplied or purchased their own around-the-clock power, costs will probably rise for consumers. But it will take some time for those costs to be felt.

In order to meet that demand, utilities and power providers will need to build more power plants, transmission lines, and — yes — poles and wires in the years to come. But recent Trump administration policies will make this harder. The reconciliation bill’s termination of wind and solar tax credits, its tariffs on electrical equipment, and a new swathe of anti-renewable regulations will make it much more expensive to add new power capacity to the strained grid. All those costs will eventually hit power bills, too, even if it takes a few years.

“We're just getting started in terms of price increases, and nothing the federal administration is doing ‘to assure American energy dominance’ is working in the right direction,” Kozel said. “They’re increasing all the headwinds.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

A conversation on FEMA, ICE, and why local disaster response still needs federal support with the National Low-Income Housing Coalition’s Noah Patton.

Congress left for recess last week without reaching an agreement to fund the Department of Homeland Security, the parent agency of, among other offices, Customs and Border Protection, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and somewhat incongruously, the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Democrats and Republicans remain leagues apart on their primary sticking point, ending the deadly and inhumane uses of force and detention against U.S. citizens and migrant communities. That also leaves FEMA without money for payroll and non-emergency programs.

The situation at the disaster response agency was already precarious — the office has had three acting administrators in less than a year; cut thousands of staff with another 10,000 on the chopping block; and has blocked and delayed funding to its local partners, including pausing the issuance of its Emergency Management Performance Grants, which are used for staffing, training, and equipping state-, city-, and tribal-level teams, pending updated population statistics post deportations.

Even so, FEMA remains technically capable of fulfilling its congressionally mandated duties due to an estimated $7 billion that remains in its Disaster Relief Fund. Still, the shutdown has placed renewed scrutiny on DHS Secretary Kristi Noem’s oversight of the agency. It has also elevated existing questions about what FEMA is doing alongside CBP and ICE in the first place.

To learn more about how the effects of the shutdown are trickling down through FEMA’s local operations, I spoke with Noah Patton, the director of disaster recovery at the National Low-Income Housing Coalition, which has publicly condemned the use of FEMA funding as a “political bargaining chip to allow ICE and CBP to continue their ongoing and imminent threats to the areas where they operate.”

When asked for comment, a FEMA spokesperson directed me to a DHS press release titled “Another Democrat Government Shutdown Dramatically Hurts America’s National Security.”

The conversation below has been edited for length and clarity.

Why is the DHS shutdown an issue you care about as a low-income housing organization? What are the stakes?

How the country responds to and recovers from disasters is inextricably linked to the issue of affordable housing. Often, households with the lowest incomes are in areas with the highest risk of disaster impacts. Our system has a lot of cracks in it. If you don’t have a rainy day fund for such things; if you’re someone who is not fully insured; if you have non-permanent employment — when disasters occur, you’re going to be hit the hardest. At the same time, you’ll receive the least assistance.

That not only exacerbates existing economic issues but also reduces the affordable housing stock available to the lowest-income households, as units are physically removed from the market when they’re destroyed or damaged by disasters.

What disasters are we talking about specifically at the moment? Are reimbursements for, say, the recent winter storms impacted by the shutdown?

Typically, when the [Disaster Relief Fund] is low, FEMA will implement critical needs funding. It pauses reimbursements for non-specific disaster-response projects and reallocates funds to preserve operational capacity for direct disaster response. That hasn’t happened yet because the DRF has sufficient funds. On the administrative end, reimbursements will be processed as we go along.

Is there anything you’re concerned about in the short term with regard to the DHS shutdown? Or has NLIHC pushed for the depoliticization of FEMA funding because of the cascading effects for the people you advocate for?

FEMA is okay as of right now. The need to stop ICE and CBP and the violence in communities across the country is taking precedence. We appreciate Congress’ interest in ensuring FEMA is adequately funded, but the DHS appropriations bill is not the only vehicle for providing FEMA funding. That’s why we’ve been pushing for a disaster-specific supplemental spending bill. That bill could also have longer-term assistance under HUD for places like Alaska [following Typhoon Halong], Los Angeles [following the January 2025 wildfires], and St. Louis [following the May 2025 tornado].

Maybe you’ve already answered my next question: How has NLIHC been navigating the tension between condemning ICE and CBP, while at the same time pushing for FEMA funding?

We have been big supporters of the House’s FEMA Act: the Fixing Emergency Management for Americans Act. It’s a bill that would remove FEMA from DHS, reestablish it as an independent agency as it was prior to 2003, and implement reforms to expand access to federal assistance for households with the lowest incomes after disasters. We’ve been supporters of that bill since it came out.

I’d also say, in the short term, I don’t see a huge amount of impact on the disaster response and recovery systems. It’s worth pausing on that, given everything going on with ICE and CBP.

What else is on your minds right now at NLIHC?

Much of the work we’re doing stems from the rapid, forced decentralization of the federal government’s emergency management capability — because emergency response and recovery now falls to the states. But many states lack robust disaster response and recovery programs. The state of Oklahoma, for example — I think their Emergency Management Office is 90% federally funded.

The administration’s pull-back of state-level emergency management performance grants and the coordination FEMA was providing on that will get the ball rolling; as we’ve seen in other disasters, the ball ends at households with the lowest incomes being the most impacted. We’re trying to head that off by coordinating advocates at the state and local levels to work with their local governments and facilitate more robust conversations on emergency management and related programs. A good example of that would be what we’re seeing in Washington State after the flooding from the atmospheric rivers. They have not received a disaster declaration from FEMA, so they’re not receiving federal assistance, but people are experiencing homelessness due to those floods. We’re working with folks there to craft programs that ensure that, in the absence of federal assistance, some form of aid continues.

For many years, the federal government was heavily involved in emergency management and served as the main coordinator. They were the source of the vast, vast, vast majority of funding. Now we’re looking toward a world where that’s less true, and where state-level mechanisms will be all the more important. Even if the FEMA Act is passed, it encourages state-level systems to emerge for responding to and recovering from disasters. We’re adding a focus to that state-level work that we didn’t necessarily need before.

The Trump administration has justified its defunding of FEMA by saying, “Well, disaster response is local, so this should be the responsibility of the states.” But like you were saying, places like Oklahoma get all their support from the federal government to begin with.

They always say, “Disaster response is local” because operationally, it needs to be. You’re not going to have a FEMA guy parachute in and start telling the local firefighters and cops what to do; that’s best handled by the folks who are on the ground and are familiar with their communities.

But it’s wrong to say, “If all disaster response is local, then why are we even involved?” FEMA provides the coordination and additional resources that are pivotal. Federal resources are allocated to local officials to respond to the disaster. The salaries of all those local emergency managers — at least, a high percentage of them — that money comes from the feds.

If the shutdown continues much longer, would that be another impact: local emergency managers not receiving their salaries?

The grant-making fight is separate. The administration is trying to slow down the flow of [emergency management preparedness grants] to state governments. Several states have filed high-profile lawsuits to obtain the grants that the federal government arbitrarily paused. Regardless of any shutdown, that will still be an issue.

On Georgia’s utility regulator, copper prices, and greening Mardi Gras

Current conditions: Multiple wildfires are raging on Oklahoma’s panhandle border with Texas • New York City and its suburbs are under a weather advisory over dense fog this morning • Ahmedabad, the largest city in the northwest Indian state of Gujarat, is facing temperatures as much as 4 degrees Celsius higher than historical averages this week.

The United States could still withdraw from the International Energy Agency if the Paris-based watchdog, considered one of the leading sources of global data and forecasts on energy demand, continues to promote and plan for “ridiculous” net-zero scenarios by 2050. That’s what Secretary of Energy Chris Wright said on stage Tuesday at a conference in the French capital. Noting that the IEA was founded in the wake of the oil embargoes that accompanied the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the Trump administration wants the organization to refocus on issues of energy security and poverty, Wright said. He cited a recent effort to promote clean cooking fuels for the 2 billion people who still lack regular access to energy — more than 2 million of whom are estimated to die each year from exposure to fumes from igniting wood, crop residue, or dung indoors — as evidence that the IEA was shifting in Washington’s direction. But, Wright said, “We’re definitely not satisfied. We’re not there yet.” Wright described decarbonization policies as “politicians’ dreams about greater control” through driving “up the price of energy so high that the demand for energy” plummets. “To me, that’s inhuman,” Wright said. “It’s immoral. It’s totally unrealistic. It’s not going to happen. And if so much of the data reporting agencies are on these sort of left-wing big government fantasies, that just distorts” the IEA’s mission.

Wright didn’t, however, just come to Paris to chastise the Europeans. Prompted by a remark from Jean-Luc Palayer, the top U.S. executive of French uranium giant Orano, Wright called the company “fantastic” and praised plans to build new enrichment facilities and bring waste reprocessing to America. While the French, Russians, and Japanese have long recycled spent nuclear waste into fresh fuel, the U.S. briefly but “foolishly” banned commercial reprocessing in the 1970s, Wright said, and never got an industry going again. As a result, all the spent fuel from the past seven decades of nuclear energy production is sitting on site in swimming pools or dry cask storage. “We want to have a nuclear renaissance. We have got to get serious about this stuff. So we will start reprocessing, likely in partnership with Orano,” Wright said. Designating Yucca Mountain as the first U.S. permanent repository for nuclear waste set the project in Nevada up for failure in the early 2000s, Wright added. “In the United States, we’ve tried to find a permanent repository for waste and we’ve had, I think, the wrong approach,” he noted. The Trump administration, he said, was “doing it differently” by inviting states to submit proposals for federally backed campuses to host nuclear enrichment and waste reprocessing facilities. Still, reprocessing leaves behind a small amount of waste that needs to be buried, so, Wright said, “we’re going to develop multiple long-term repositories.”

The Trump administration could tweak tariffs on metals and other materials, U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer said Tuesday. During an appearance on CNBC’s “Squawk Box,” Greer said he’d heard from companies who claimed they needed to hire more workers to navigate the tariffs. “You may want to sometimes adjust the way some of the tariffs are for compliance purposes,” he said. “We’re not trying to have people deal with so much beancounting that they’re not running their company correctly.” Still, he said, the U.S. is “shipping more steel than ever,” and has, as I reported in a newsletter last month, the first new aluminum smelter in the works in half a century. “So clearly those [tariffs] are going in the right direction and they’re going to stay in place.”

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

California Governor Gavin Newsom, widely seen as a frontrunner for the Democratic presidential nod in two years, is already staking out an alternative energy approach to Trump. During a stop in London on his tour of Europe, Newsom this week signed onto a new pact with British Energy Secretary Ed Miliband, pledging to work together with the United Kingdom on deploying more clean energy technologies such as offshore wind in the nation’s most populous state. One of the biggest winners of the deal, according to Politico, is Octopus Energy, the biggest British energy supplier, which is looking to enter the California market. But the agreement also sets the stage for more joint atmospheric research between California and the U.K. “California is the best place in America to invest in a clean economy because we set clear goals and we deliver,” Newsom said. “Today, we deepened our partnership with the United Kingdom on climate action and welcomed nearly a billion dollars in clean tech investment from Octopus Energy.”

France, meanwhile, is realigning its energy plan for the next nine years in a way the Trump administration will like. The draft version of the plan released last year called for 90 gigawatts of installed solar capacity by 2035. But the latest plan published last week reduced the target to a range of 55 to 80 gigawatts. Onshore wind falls to 35 to 40 gigawatts from 40 to 45 gigawatts. Offshore wind drops to 15 gigawatts from 18 gigawatts. Instead, Renewables Now reported, the country is betting on a nuclear revival.

When Democrats unseated two Republicans on Georgia’s five-member Public Service Commission, the upsets signaled a change to the state’s utility regulator so big one expert described it to Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo at the time as “seismic.” Now one of the three remaining Republicans on the body is stepping aside in this year’s election. In a lengthy post on X, Tricia Pridemore said she would end her eight-year tenure on the commission by opting out of reelection. “I have consistently championed common-sense, America First policies that prioritize energy independence, grid reliability, and practical solutions over partisan rhetoric,” wrote Pridemore, who both championed the nuclear expansion at Georgia Power’s Plant Vogtle and pushed for more natural gas generation. “These efforts have laid the foundation for job creation, national security, and opportunity across our state. By emphasizing results over rhetoric, we have positioned Georgia as a leader in affordability, reliability, and forward-thinking energy planning.”

BHP, the world’s most valuable mining company, reported a nearly 30% spike in net profits for the first half of this year thanks to soaring demand for copper. The Australian giant’s chief executive, Mike Henry, said the earnings marked a “milestone” as copper contributed the largest share of its profit for the first time, accounting for 51% of income before interest, tax, depreciation, and amortization. The company also signed a $4.3 billion deal with Canada’s Wheaton Precious Metals to supply silver from its Antamina mine in Peru in a deal the Financial Times called “the largest of its kind for so-called precious metals streaming, where miners make deals to sell gold or silver that is a byproduct of their main business.”

The mining companies the Trump administration is investing in, on the other hand, may have less rosy news for the market. Back in October, I told you that the U.S. was taking a stake in Trilogy Metals after approving its request to build a mining road in a remote corner of Alaska that’s largely untouched by industry. On Tuesday, the company reported a net loss of $42 million. The loss largely stemmed from what Mining.com called “the treatment of the proposed U.S. government’s investment as a derivative financial instrument” under standard American accounting rules. The accounting impact, however, had no effect on the cash the company had on hand and “is expected to resolve once applicable conditions are met.”

“It’s an environmental catastrophe.” That’s how Brett Davis, the head of a nonprofit that advocates for less pollution at Mardi Gras, referred to the waste the carnival generates each year in New Orleans. Data the city’s sanitation department gave The New York Times showed that the weekslong party produced an average of 1,123 tons of waste per year for the last decade. Reusing the plastic beads that became popular in the 1970s when manufacturing moved overseas and made cheap goods widely accessible just amounts to “recirculating toxic plastic junk no one wants,” Davis told the newspaper. Instead, he’s sold more than $1 million in more sustainable alternative items to throw during the parade, including jambalaya mix, native flower start kits, and plant-based glitter.

Batteries can only get so small so fast. But there’s more than one way to get weight out of an electric car.

Batteries are the bugaboo. We know that. Electric cars are, at some level, just giant batteries on wheels, and building those big units cheaply enough is the key to making EVs truly cost-competitive with fossil fuel-burning trucks and cars and SUVs.

But that isn’t the end of the story. As automakers struggle to lower the cost to build their vehicles amid a turbulent time for EVs in America, they’re looking for any way to shave off a little expense. The target of late? Plain old wires.

Last month, when General Motors had to brace its investors for billions in losses related to curtailing its EV efforts and shifting factories back to combustion, it outlined cost-saving measures meant to get things moving in the right direction. While much of the focus was on using battery chemistries like lithium ion phosphate, otherwise known as LFP, that are cheaper to build, CEO Mary Barra noted that the engineers on every one of the company’s EVs were working “to take out costs beyond the battery,” of which cutting wiring will be a part.

They are not alone in this obsession. Coming into a do-or-die year with the arrival of the R2 SUV, Rivian said it had figured out how to cut two miles of wires out of the design, a coup that also cuts 44 pounds from the vehicle’s weight (this is still a 5,000-pound EV, but every bit counts). Ford has become obsessed with figuring out smarter and cheaper ways for its money-hemorrhaging EV division to build cars; the company admitted, after tearing down a Tesla Model 3 to look inside, that its Mustang Mach-E EV had a mile of extra and possibly unnecessary wiring compared to its rival.

A bunch of wires sounds like an awfully mundane concern for cars so sophisticated. But while every foot adds cost and weight, the obsession with stripping out wiring is about something deeper — the broad move to redefine how cars are designed and built.

It so happens that the age of the electric vehicle is also the age of the software-defined car. Although automobiles were born as purely mechanical devices, code has been creeping in for decades, and software is needed to manage the computerized fuel injection systems and on-board diagnostic systems that explain why your Check Engine light is illuminated. Tesla took this idea to extremes when it routed the driver’s entire user interface through a giant central touchscreen. This was the car built like a phone, enabling software updates and new features to be rolled out years after someone bought the car.

As Tesla ruled the EV industry in the 2010s, the smartphone-on-wheels philosophy spread. But it requires a lot of computing infrastructure to run a car on software, which adds complexity and weight. That’s why carmakers have spent so much time in the past couple of years talking about wires. Their challenge (among many) is to simplify an EV’s production without sacrificing any of its capability.

Consider what Rivian is attempting to do with the R2. As InsideEVs explains, electric cars have exploded in their need for electronic control units, the embedded computing brains that control various systems. Some models now need more than 100 to manage all the software-defined components. Rivian managed to sink the number to just seven, and thus shave even more cost off the R2, through a “zonal” scheme where the ECUs control all the systems located in their particular region of the vehicle.

Compared to an older, centralized system that connects all the components via long wires, the savings are remarkable. As Rivian chief executive RJ Scaringe posted on X: “The R2 harness improves massively over the R1 Gen 2 harness. Building on the backbone of our network architecture and zonal ECUs, we focused on ease of install in the plant and overall simplification through integrated design — less wires, less clips and far fewer splices!”

Legacy automakers, meanwhile, are racing to catch up. Even those that have built decent-selling quality EVs to date have not come close to matching the software sophistication of Tesla and Rivian. But they have begun to see the light — not just about fancy iPads in the cockpit, but also about how the software-defined vehicle can help them to run their factories in a simpler and cheaper way.

How those companies approach the software-defined car will define them in the years to come. By 2028, GM hopes to have finished its next-gen software platform that “will unite every major system from propulsion to infotainment and safety on a single, high-speed compute core,” according to Barra. The hope is that this approach not only cuts down on wiring and simplifies manufacturing, but also makes Chevys and Cadillacs more easily updatable and better-equipped for the self-driving future.

In that sense, it’s not about the wires. It’s about all the trends that have come to dominate electric vehicles — affordability, functionality, and autonomy — colliding head-on.