You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

In this special episode, Rob goes over the repeal of the “endangerment finding” for greenhouse gases with Harvard Law School’s Jody Freeman.

President Trump has opened a new and aggressive war on the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to limit climate pollution. Last week, the EPA formally repealed its scientific determination that greenhouse gases endanger human health and the environment.

On this week’s episode of Shift Key, we find out what happens next.

Rob is joined by Jody Freeman, the director of the Environmental and Energy Law Program at Harvard Law School, to discuss the Trump administration’s war on the endangerment finding. They chat about how the Trump administration has already changed its argument since last summer, whether the Supreme Court will buy what it’s selling, and what it all means for the future of climate law.

They also talk about whether the Clean Air Act has ever been an effective tool to fight greenhouse gas pollution — and whether the repeal could bring any upside for states and cities.

Shift Key is hosted by Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Here is an excerpt from our conversation:

Jody Freeman: The scientific community, you know, filed comments on this proposal and just knocked all of the claims in the report out of the box, and made clear how much evidence not only there was in 2009, for the endangerment finding, but much more now. And they made this very clear. And the National Academies of Science report was excellent on this. So they did their job. They reflected the state of the science and EPA has dropped any frontal attack on the science underlying the endangerment finding.

Now, it’s funny. My reaction to that is like twofold. One, like, yay science, right? Go science. But two is, okay, well, now the proposal seems a little less crazy, right? Or the rule seems a little less crazy. But I still think they had to fight back on this sort of abuse of the scientific record. And now it is the statutory arguments based on the meaning of these words in the law. And they think that they can get the Supreme Court to bite on their interpretation.

And they’re throwing all of these recent decisions that the Supreme Court made into the argument to say, look what you’ve done here. Look what you’ve done there. You’ve said that agencies need explicit authority to do big things. Well, this is a really big thing. And they characterize regulating transportation sector emissions as forcing a transition to EVs. And so to characterize it as this transition unheralded, you know, and they need explicit authority, they’re trying to get the court to bite. And, you know, they might succeed, but I still think some of these arguments are a real stretch.

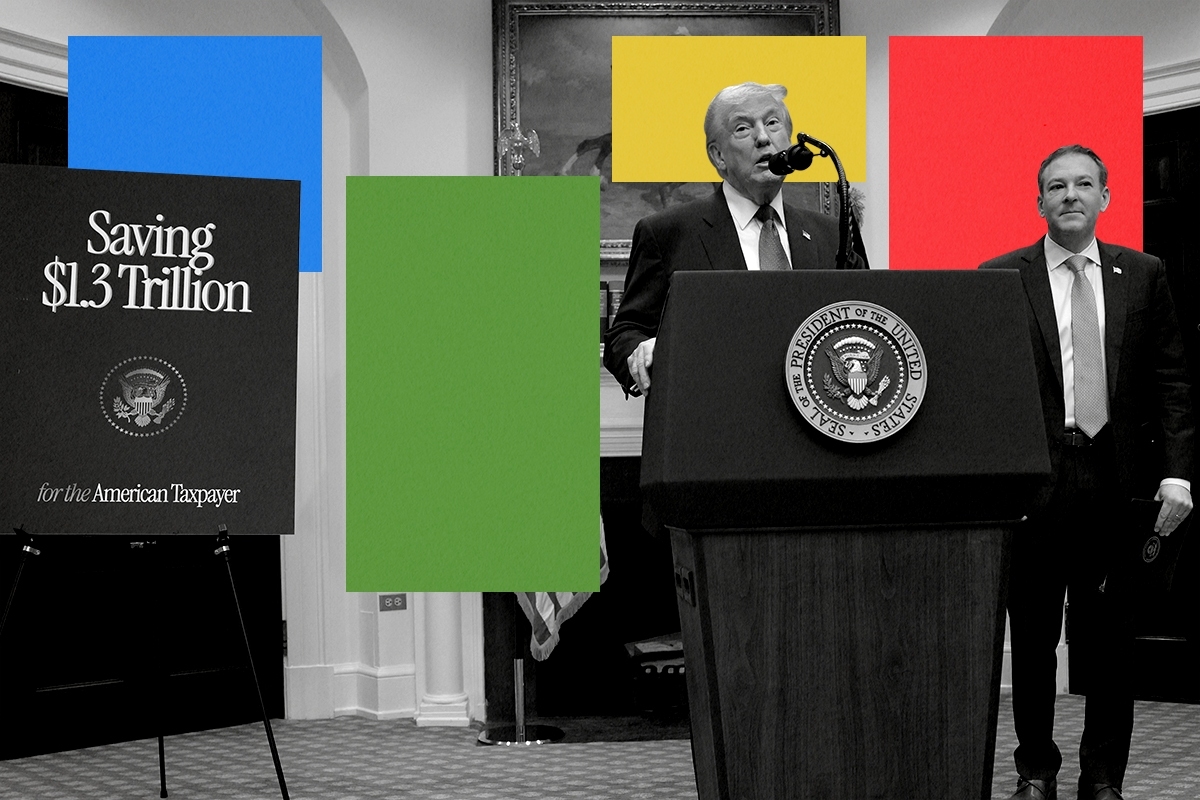

Robinson Meyer: One thing I would call out about this is that while they’ve taken the climate denialism out of the legal argument, they cannot actually take it out of the political argument. And even yesterday, as the president was announcing this action — which, I would add, they described strictly in deregulatory terms. In fact, they seemed eager to describe it not as an environmental action, not as something that had anything to do with air and water, not even as a place where they were. They mentioned the Green New Scam, quote-unquote, a few times. But mostly this was about, oh, this is the biggest deregulatory action in American history.

It’s all about deregulation, not about like something about the environment, you know, or something about like we’re pushing back on those radicals. It was ideological in tone. But even in this case, the president couldn’t help himself but describe climate change as, I think the term he used is a giant scam. You know, like even though they’ve taken, surgically removed the climate denialism from the legal argument, it has remained in the carapace that surrounds the actual ...

Freeman: And I understand what they say publicly is, you know, deeply ideological sounding and all about climate is a hoax and all that stuff. But I think we make a mistake … You know, we all get upset about the extent to which the administration will not admit physics is a reality, you know, and science is real and so on. But, you know, we shouldn’t get distracted into jumping up and down about that. We should worry about their legal arguments here and take them seriously.

You can find a full transcript of the episode here.

Mentioned:

From Heatmap: The 3 Arguments Trump Used to Gut Greenhouse Gas Regulations

Previously on Shift Key: Trump’s Move to Kill the Clean Air Act’s Climate Authority Forever

Rob on the Loper Bright case and other Supreme Court attacks on the EPAThis episode of Shift Key is sponsored by ...

This episode of Shift Key is sponsored by ...

Accelerate your clean energy career with Yale’s online certificate programs. Explore the 10-month Financing and Deploying Clean Energy program or the 5-month Clean and Equitable Energy Development program. Use referral code HeatMap26 and get your application in by the priority deadline for $500 off tuition to one of Yale’s online certificate programs in clean energy. Learn more at cbey.yale.edu/online-learning-opportunities.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The administration has begun shuffling projects forward as court challenges against the freeze heat up.

The Trump administration really wants you to think it’s thawing the freeze on renewable energy projects. Whether this is a genuine face turn or a play to curry favor with the courts and Congress, however, is less clear.

In the face of pressures such as surging energy demand from artificial intelligence and lobbying from prominent figures on the right, including the wife of Trump’s deputy chief of staff, the Bureau of Land Management has unlocked environmental permitting processes in recent weeks for a substantial number of renewable energy projects. Public documents, media reports, and official agency correspondence with stakeholders on the ground all show projects that had ground to a halt now lurching forward.

What has gone relatively unnoticed in all this is that the Trump administration has used this momentum to argue against a lawsuit filed by renewable energy groups challenging Trump’s permitting freeze. In January, for instance, Heatmap was first to report that the administration had lifted its ban on eagle take permits for wind projects. As we predicted at the time, after easing that restriction, Trump’s Justice Department has argued that the judge in the permitting freeze case should reject calls for an injunction. “Arguments against the so-called Eagle Permit Ban are perhaps the easiest to reject. [The Fish and Wildlife Service] has lifted the temporary pause on the issuance of Eagle take permits,” DOJ lawyers argued in a legal brief in February.

On February 26, E&E News first reported on Interior’s permitting freeze melting, citing three unnamed career agency officials who said that “at least 20 commercial-scale” solar projects would advance forward. Those projects include each of the seven segments of the Esmeralda mega-project that Heatmap was first to report was killed last fall. E&E News also reported that Jove Solar in Arizona, the Redonda and Bajada solar projects in California and three Nevada solar projects – Boulder Solar III, Dry Lake East and Libra Solar – will proceed in some fashion. Libra Solar received its final environmental approval in December but hasn’t gotten its formal right-of-way for construction.

Since then, Heatmap has learned of four other projects on the list, all in Nevada: Mosey Energy Center, Kawich Energy Center, Purple Sage Energy Center and Rock Valley Energy Center.

Things also seem to be moving on the transmission front in ways that will benefit solar. BLM posted the final environmental impact statement for upgrades to NextEra’s GridLance West transmission project in Nevada, which is expected to connect to solar facilities. And NV Energy’s Greenlink North transmission line is now scheduled to receive a final federal decision in June.

On wind, the administration silently advanced the Lucky Star transmission line in Wyoming, which we’ve covered as a bellwether for the state of the permitting process. We were first to report that BLM sent local officials in Wyoming a draft environmental review document a year ago signaling that the transmission line would be approved — then the whole thing inexplicably ground to a halt. Now things are moving forward again. In early February, BLM posted the final environmental review for Lucky Star online without any public notice or press release.

There are certainly reasons why Trump would allow renewables development to move forward at this juncture.

The president is under incredible pressure to get as much energy as possible onto the electric grid to power AI data centers without causing undue harm to consumers’ pocketbooks. According to the Wall Street Journal, the oil industry is urging him to move renewables permitting forward so Democrats come back to the table on a permitting deal.

Then there’s the MAGAverse’s sudden love affair with solar energy. Katie Miller, wife of White House deputy chief of staff Stephen Miller, has suddenly become a pro-solar advocate at the same time as a PR campaign funded by members of American Clean Power claims to be doing paid media partnerships with her. (Miller has denied being paid by ACP or the campaign.) Former Trump senior adviser Kellyanne Conway is now touting polls about solar’s popularity for “energy security” reasons, and Trump pollster Tony Fabrizio just dropped a First Solar-funded survey showing that roughly half of Trump voters support solar farms.

This timing is also conspicuously coincidental. One day before the E&E News story, the Justice Department was granted an extension until March 16 to file updated rebuttals in the freeze case before any oral arguments or rulings on injunctions. In other court filings submitted by the Justice Department, BLM career staff acknowledge they’ve met with people behind multiple solar projects referenced in the lawsuit since it was filed. It wouldn’t be surprising if a big set of solar projects got their permitting process unlocked right around that March 16 deadline.

Kevin Emmerich, co-founder of Western environmental group Basin & Range Watch, told me it’s important to recognize that not all of these projects are getting final approvals; some of this stuff is more piecemeal or procedural. As an advocate who wants more responsible stewardship of public lands and is opposed to lots of this, Emmerich is actually quite troubled by the way Trump is going back on the pause. That is especially true after the Supreme Court’s 2025 ruling in the Seven Counties case, which limited the scope of environmental reviews, not to mention Trump-era changes in regulation and agency leadership.

“They put a lot of scrutiny on these projects, and for a while there we didn’t think they were going to move, period,” Emmerich told me. “We’re actually a little bit bummed out about this because some of these we identified as having really big environmental impacts. We’re seeing this as a perfect storm for those of us worried about public land being taken over by energy because the weakening of NEPA is going to be good for a lot of these people, a lot of these developers.”

BLM would not tell me why this thaw is happening now. When reached for comment, the agency replied with an unsigned statement that the Interior Department “is actively reviewing permitting for large-scale onshore solar projects” through a “comprehensive” process with “consistent standards” – an allusion to the web of review criteria renewable energy developers called a de facto freeze on permits. “This comprehensive review process ensures that projects — whether on federal, state, or private lands — receive appropriate oversight whenever federal resources, permits, or consultations are involved.”

Current conditions: May-like warmth is sending temperatures across the Midwest and Northeast up to 25 degrees Fahrenheit above historical averages • Dangerous rip currents are yanking at Florida’s Atlantic coast • South Africa’s Northern Cape is bracing for what’s locally known as an orange-level 5 storm bringing intense flooding.

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission granted a construction permit for the Bill Gates-backed small modular reactor startup TerraPower’s flagship project to convert an old coal plant in Kemmerer, Wyoming, to a next-generation nuclear station. The approval marked the first time a commercial-scale fourth-generation nuclear reactor — the TerraPower design uses liquid sodium metal as a coolant instead of water, as all other commercial reactors in the United States use — has received the green light from regulators this century. “Today is a historic day for the United States’ nuclear industry,” Chris Levesque, TerraPower’s chief executive, said in a statement. “We are beyond proud to receive a positive vote from the Nuclear Regulatory Commissioners to grant us our construction permit for Kemmerer Unit One.”

While the permit is a milestone for the U.S., it’s also a sign of how far ahead China is in the race to dominate the global nuclear industry. TerraPower had initially planned to build its first reactors in China back in the 2010s before relations between Washington and Beijing soured. In the meantime, China deployed the world’s only commercial-scale fourth-generation reactor, using a high-temperature gas-cooled design, all while building out more traditional light water reactors than the rest of the world combined. Just this week, construction crews lifted the reactor pressure vessel into place for the latest natively-designed Hualong One at the Lufeng nuclear plant in Guangdong province.

Sodium-ion batteries and novel technologies to store energy for long durations are loosening lithium’s grasp on the storage market — but not by that much. Global lithium demand is on track to surpass 13 million metric tons by 2050, the consultancy Wood Mackenzie estimated in its latest forecast covered in Mining.com. That’s according to an accelerated energy transition scenario that more than doubles the base-case projections. Under those conditions, supply shortages could start to show as early as 2028 if the industry doesn’t pony up $276 billion in new capacity, the report warned. Under a less ambitious decarbonization scenario, the estimates fall to about 5.6 million tons of lithium.

The Department of Energy ordered the last coal-fired power plant in Washington State to remain open past its planned retirement last year on the grounds that losing the generation would put the grid at risk. At least for the near future, however, the station’s owners say they have little need to fire up the coal furnaces. On an earnings call last week, TransAlta CEO John Kousinioris said that, given “how flush” Washington is with hydropower, the cost of firing up the coal plant wasn’t worth it most of the time. Instead, the utility said it wanted to convert the station into a gas-fired plant. In the meantime, Kousinioris said, “our primary focus is more on getting clarity on the existing order,” according to Utility Dive.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

The European Union has proposed setting a quota for publicly funded projects to source 25% of their steel from low-carbon sources. The bloc’s long-delayed Industrial Acceleration Act came out this week with formal pitches to fulfill Brussels’ goal to revive Europe’s steelmaking industry with cleaner technology. Still, the trade group Hydrogen Europe warned that the rules neither accounted for limited direct subsidies for key technologies to develop clean fuel supply chains nor the absence of similar quotas in other industries such as housing construction or automotive construction. “We call on co-legislators to strengthen the Act and close the gaps on ambition, scope, and clarity. Europe must ensure that its industry can grow, compete, and lead globally in strategic clean technologies like hydrogen,” Jorgo Chatzimarkakis, chief executive of Hydrogen Europe, said in a statement. “Hydrogen Europe and its members stand ready to support policymakers to ensure the Industrial Accelerator Act delivers on its initial promises.”

A week ago, Google backed a deal to build what Heatmap’s Katie Brigham said “would be the largest battery in the world by energy capacity. Now China is building by far the world’s largest commercial experiment yet in using compressed air to store energy. The $520 million project, called the Huai’an Salt Cavern CAES demonstration plant, includes two 300-megawatt units. The first unit came online in December, and the second switched on in recent weeks, according to Renewables Now. At peak output, the facility could power 600,000 homes. The Trump administration initially dithered on giving out funding to compressed air energy storage projects in the U.S. But as of December, a major project in California appeared to be moving forward.

Breaking China’s monopolies over key metals needed for modern energy technology and weapons is, as ever, a bipartisan endeavor. A top Democrat just backed the Senate’s push to support a critical minerals stockpile. In a post on X, Michigan Senator Elissa Slotkin pitched legislation she said “ensures we have a plant to stockpile critical minerals and protect our economy. This is an important step to ensure hostile nations like China never have a veto over our national security or economy.”

The Trump administration’s rollback of coal plant emissions standards means that mercury is on the menu again.

It started with the cats. In the seaside town of Minamata, on the west coast of the most southerly of Japan’s main islands, Kyushu, the cats seemed to have gone mad — convulsing, twirling, drooling, and even jumping into the ocean in what looked like suicides. Locals started referring to “dancing cat fever.” Then the symptoms began to appear in their newborns and children.

Now, nearly 70 years later, Minimata is a cautionary tale of industrial greed and its consequences. Dancing cat fever and “Minamata disease” were both the outward effects of severe mercury poisoning, caused by a local chemical company dumping methylmercury waste into the local bay. Between the first recognized case in 1956 and 2001, more than 2,200 people were recognized as victims of the pollution, which entered the population through their seafood-heavy diets. Mercury is a bioaccumulator, meaning it builds up in the tissues of organisms as it moves up the food chain from contaminated water to shellfish to small fish to apex predators: Tuna. Cats. People.

In 2013, 140 countries, including the U.S., joined the Minamata Convention, pledging to learn from the mistakes of the past and to control the release of mercury into the environment. That included, explicitly, mercury in emissions from “coal-fired power plants.” Last month, however, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency retreated from the convention by abandoning the 2024 Mercury and Air Toxics Standards, which had reduced allowable mercury pollution from coal-fired plants by as much as 90%. Nearly all of the 219 operating coal-fired plants in the U.S. already meet the previous, looser standard, set in 2012; Trump’s EPA has argued that returning to the older rules will save Americans $670 million in regulatory compliance costs by 2037.

The rollback — while not a surprise from an administration that has long fetishized coal — came as a source of immense frustration to scientists, biologists, and activists who’ve dedicated their careers to highlighting the dangers of environmental contaminants. Nearly all human exposure to methylmercury in the United States comes from eating seafood, according to the EPA, and it’s well-documented that adding more mercury to the atmosphere will increase levels in fish, even those caught far from fenceline communities.

“Mercury is an extremely toxic metal,” Nicholas Fisher, an expert in marine pollution at Stony Brook University, told me. “It’s probably among the most toxic of all the metals, and it’s been known for centuries.” In his opinion, it’s unthinkable that there is still any question of mercury regulations making Americans safer.

Gabriel Filippelli, the executive director of the Indiana University Environmental Resilience Institute, concurred. “Mercury is not a trivial pollutant,” he told me. “Elevated mercury levels cost millions of IQ points across the country.” The EPA rollback “actually costs people brain power.”

When coal burns in a power plant, it releases mercury into the air, where it can travel great distances and eventually end up in the water. “There is no such thing as a local mercury problem,” Filippelli said. He recalled a 2011 study that looked at Indianapolis Power & Light, a former coal plant that has since transitioned to natural gas, in which his team found “a huge plume of mercury in solids downwind” of the plant, as well as in nearby rivers that were “transporting it tens of kilometers away into places where people fish and eat what they catch.”

Earthworms and small aquatic organisms convert mercury in soils and runoff into methylmercury, a highly toxic form that presents the most danger to people, children, and the fetuses of pregnant women as it moves up the food chain. Though about 70% of mercury deposited in the United States comes from outside the country — China, for example, is the second-greatest source of mercury in the Great Lakes Basin after the U.S., per the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration — that still leaves a significant chunk of pollution under the EPA’s control.

There is, in theory, another line of defense beyond the EPA. For recreational fishers, of whom there are nearly 60 million in the country each year, state-level advisories on which waterways are safe to fish in based on tests of methylmercury concentrations in the fish help guide decisions about what is safe to eat. Oregon, for example, advises that people not eat more than one “resident fish,” such as bass, walleye, and carp, caught from the Columbia River per week — and not eat any other seafood during that time, either. Forty-nine states have some such advisories in place; the only state that doesn’t, coal-friendly Wyoming, has refused to test its fish. One also imagines that safe waterways will start to become more limited if the coal-powered plants the Trump administration is propping up forgo the expensive equipment necessary to scrub their emissions of heavy metals.

“It’s not something where you’re going to see a dramatic change overnight,” Tasha Stoiber, a senior scientist with the Environmental Working Group, a research and advocacy nonprofit that focuses on toxic chemicals, told me. “But depending on the water body that you’re fishing in, you want to seek out state advisories.”

For people who prefer to buy their fish at the store, the Food and Drug Administration sets limits on the amount of mercury allowed in commercial seafood. But Kevin McCay, the chief operations officer at the seafood company Safe Catch, told me the FDA’s limit of 1 part per million for methylmercury is outrageously high compared with limits in the European Union and Japan. “It has to be glowing red before the FDA is actually going to do anything,” he said. (Watchdog groups have likewise warned that the hemorrhaging of civil servants from the FDA will have downstream consequences for food safety.)

McCay also told me that he “certainly” expects mercury levels in the fish to rise due to the EPA’s decision. Unlike other canned tuna companies that test batches of fish, Safe Catch drills a small test hole in every fish it buys to ensure the mercury content is well below the FDA’s limits. (Fish that are lower on the food chain, like salmon, are the safest choices, while fish at the top of the food chain, like tuna, sharks, and swordfish, are the worst.)

The obsessive oversight gives the company a front-seat view of where and how methylmercury is working its way up the food chain, and McCay worries his company could face more limited sourcing options in the coming years if policies remain friendly to coal. (An independent investigation by Consumer Reports in 2023 found that even fish sourced by an ultra-cautious company like Safe Catch contain some level of mercury. “There’s probably no actual safe amount,” McCay told me, recommending that customers should eat a diverse range of seafood to limit exposure.)

Even people who don’t eat fish should be concerned, though. That’s because, as Filippelli told me, “a lot of [contaminated] fish meal is being incorporated into pet food.”

There are no regulatory standards for mercury in pet foods. But avoiding mercury is not as simple as bypassing the tuna-flavored kibble, Sarrah M. Dunham-Cheatham, who authored a 2019 study on mercury in pet food, told me. Even many brands that don’t list fish among their ingredients contain fish meal that is high in mercury, she said.

Different species also have different sensitivities to mercury, with chimpanzees and cats being among the most sensitive. “I don’t want to be alarmist or scare people,” Dunham-Cheatham said. But because of the issues with labeling pet food, there isn’t much to be done to limit mercury intake in your pets — that is, short of dealing with the emissions on local and planetary scales. “We’re expecting there to be more emissions to the atmosphere, more deposition to aquatic environments, and therefore more mercury accumulated into proteins that will go into making the pet foods,” she said.

To Fisher, the Stony Brook professor, the Trump administration’s decision to walk back mercury restrictions makes no sense at all. The Ancient Romans understood the dangers of mercury; the dancing cats of Minamata are now seven decades behind us. “Why should we make the underlying assumption that the mercury is innocent until proven guilty?” he said.