You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

On uranium challenges, Cadillac’s EV dreams, and a firefighter’s firestorm

Current conditions: Atlantic hurricane season enters its peak window and a zone west of Africa is under close monitoring for high risk tropical storm development this week • A polar air mass came down from Canada and dropped temperatures 15 degrees below historical averages in the Great Plains and the Northeastern U.S. • Croatia braces for floods as up to 11 inches of rain falls on the Balkans.

Add the Department of Transportation to the list of federal agencies waging what Heatmap’s Jael Holzman called “Trump’s total war on wind.” The Transportation Department said Friday it was eliminating or withdrawing $679 million in federal funding for 12 projects across the country designed to buttress development of offshore turbines. The funding included $427 million awarded last year for upgrading a marine terminal in Humboldt County, California, meant to be used for building and launching floating wind turbines. The list also included a $48 million offshore wind port on Staten Island, $39 million for a port near Norfolk, Virginia, and $20 million for a staging terminal in Paulsboro, New Jersey. “Wasteful, wind projects are using resources that could otherwise go towards revitalizing America’s maritime industry,” Secretary of Transportation Sean Duffy said in a statement. “Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg bent over backwards to use transportation dollars for their Green New Scam agenda while ignoring the dire needs of our shipbuilding industry.”

It’s just the Trump administration’s latest attack on wind. The Department of the Interior has led the charge, launching a witch hunt against any policies perceived to favor wind power, de-designating millions of acres of federal waters for offshore wind development, and kicking off an investigation into bird deaths near turbines. Last month, the Department of Commerce joined the effort, teeing up future tariffs with its own probe into whether imported turbines pose a national security threat to the U.S. In response, the Democratic governors of New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Jersey on Monday issued a statement calling on the administration “to uphold all offshore wind permits already granted and allow these projects to be constructed.”

In what the New York Times called a “sharp escalation” of its legal strategy to fend off liability for pollution, Exxon Mobil has countersued California, accusing the state’s landmark litigation over plastic waste of defaming the oil giant. At a court hearing last month, Exxon attorney Michael P. Cash described the lawsuit California Attorney General Rob Bonta and a cadre of environmental groups first filed last year as “an attack” aimed at the oil company’s home state of Texas and said the issue should be litigated there. As Times reporter Karen Zraick noted, Cash illustrated his point by displaying “a graphic showing a missile aimed at Texas from California” and by comparing Bonta and his nonprofit allies to “The Sopranos.”

Backed by a parallel lawsuit filed by the Sierra Club, Baykeeper, Heal the Bay, and the Surfrider Foundation, Bonta sued Exxon in state court on the grounds that the company had deceived Californians by “promising that recycling could and would solve the ever-growing plastic waste crisis,” alleging that the pollution had created a public nuisance and sought damages worth “multiple billions of dollars.” The lawsuit mirrors past litigation over planet-heating emissions, but targets the petrochemical division that has been one of the fastest-growing for Exxon and other oil giants. The courtroom drama came right as international negotiations in Geneva over a global treaty to curb plastic pollution failed after the United States joined Russia and other petrostates to block measures supported by more than 100 other nations that would have curbed production.

In North America, nuclear fuel may soon become harder to come by. Canadian uranium giant Cameco has warned that delays in ramping up production at its McArthur River mine in Saskatchewan could shrink its forecast output for the year. The move came just a week after one of the world’s other major suppliers of uranium, Kazakhstan’s state-owned miner Kazatomprom, announced plans to slash its production by 10% next year.

The pullback is happening right as the U.S. nuclear industry’s dealmaking boom is taking off. Now that Trump’s tax law assured that support for atomic energy would continue, Adam Stein from the Breakthrough Institute told Heatmap’s Katie Brigham that more reactor plans are coming. “We might have seen more deals earlier this year if there wasn’t uncertainty about what was going to happen with tax credits. But now that that’s resolved, I expect to hear more later this year,” he told Katie. That includes Europe. Despite similarly lethargic construction of reactors over the last three decades, France and Germany have finally united around the need for more atomic energy to power the continent’s energy transition. A pact signed at last week’s Franco-German summit “appears to herald rapprochement on reactors,” the trade publication NucNet surmised.

Once a stodgy gas-guzzling automaker, Cadillac refashioned itself as a luxury electric vehicle maker in recent years, rising alongside Chevrolet to put General Motors in the No. 2 slot behind Tesla. Roughly 70% of buyers who purchased the electric versions of the Cadillac Optiq or Lyriq switched from other luxury brands, including 10% who previously owned Tesla. That number could rise with Tesla’s brand loyalty nosediving, as this newsletter previously reported. “We’re in a position of great momentum,” John Roth, the global vice president of Cadillac, told The New York Times. “We offer more electric S.U.V.s than any luxury manufacturer, all with more than 300 miles of driving range.” But as Times reporter Lawrence Ulrich wrote, “that moment will soon be tested” as the electric car industry reels from the repeal of tax credits in President Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill.

The challenges ahead are best illustrated through the Escalade, Cadillac’s iconic luxury SUV. The company sold just 3,800 electric Escalade IQs in the first six months of the year. While that’s a strong showing for a three-row SUV starting around $130,000, the V-8 engine gas-powered Escalade starts at about $87,000, and sold about 24,000 vehicles – roughly six times as many as the electric version.

Lawyers in Oregon are demanding the release of a firefighter arrested last week by Border Patrol while fighting a wildfire in Washington state. The man, whose name hasn’t been released, was among two firefighters cuffed in the Olympic National Forest as they fought to contain the Bear Gulch Fire that had burned about 14 square miles as of Friday and forced evacuations. The arrests sparked a political firestorm over what critics saw as a jarring example of the warped priorities of the Trump administration’s immigration crackdown. That’s particularly so in the case of this firefighter, who attorneys said had received his U-Visa certification from the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Oregon in 2017 and had submitted his U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services application the following year.

When the AP asked the Bureau of Land Management why its contracts with two firefighting companies were terminated and 42 firefighters were escorted away from Washington’s largest wildfire, the agency declined to comment. The decisions came as the American West is essentially a tinderbox. As Heatmap’s Jeva Lange reported, Washington and Oregon are both at high risk of a megafire igniting this fall.

Turns out mammoths weren’t just in the icy tundra. Scientists in Mexico discovered mammoth bones, shedding light on a once-obscure population of extinct tropical elephantids that ranged as far south as Costa Rica. In a paper published this week in Science, National Autonomous University of Mexico paleogenomicist Federico Sánchez Quinto documented the previously unknown lineage of the Santa Lucía mammoths, which he said split from northern Columbian mammoths hundreds of thousands of years ago. “If you had told me 5 years ago that I would be collecting these samples, I would have said, ‘You’re crazy,’” he said. “This paper really is an exciting beginning of something.”

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Current conditions: The Central United States is facing this year’s largest outbreak of severe weather so far, with intense thunderstorms set to hit an area stretching from Texas to the Great Lakes for the next four days • Northern India is sweltering in temperatures as high as 13 degrees Celsius above historical norms • Australia issued evacuation alerts for parts of Queensland as floodwaters inundate dozens of roads.

The price of futures contracts for crude oil fell below $85 per barrel Monday after President Donald Trump called the war against Iran “very complete, pretty much,” declaring that there was “nothing left in a military sense” in the country. “They have no navy, no communications, they’ve got no air force. Their missiles are down to a scatter. Their drones are being blown up all over the place, including their manufacturing of drones,” Trump told CBS News in a phone interview Monday. “If you look, they have nothing left.”

The dip, just a day after prices surged well past $100 per barrel, highlights what Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin described as the challenge of depending too much on fossil fuels for a payday. “Even $85 is substantially higher than the $57 per barrel price from the end of last year. At that point, forecasters from both the public and the private sectors were expecting oil to stick around $60 a barrel through 2026,” he wrote. “Of course, crude oil itself is not something any consumer buys — but those high prices would likely feed through to higher consumer prices throughout the U.S. economy.”

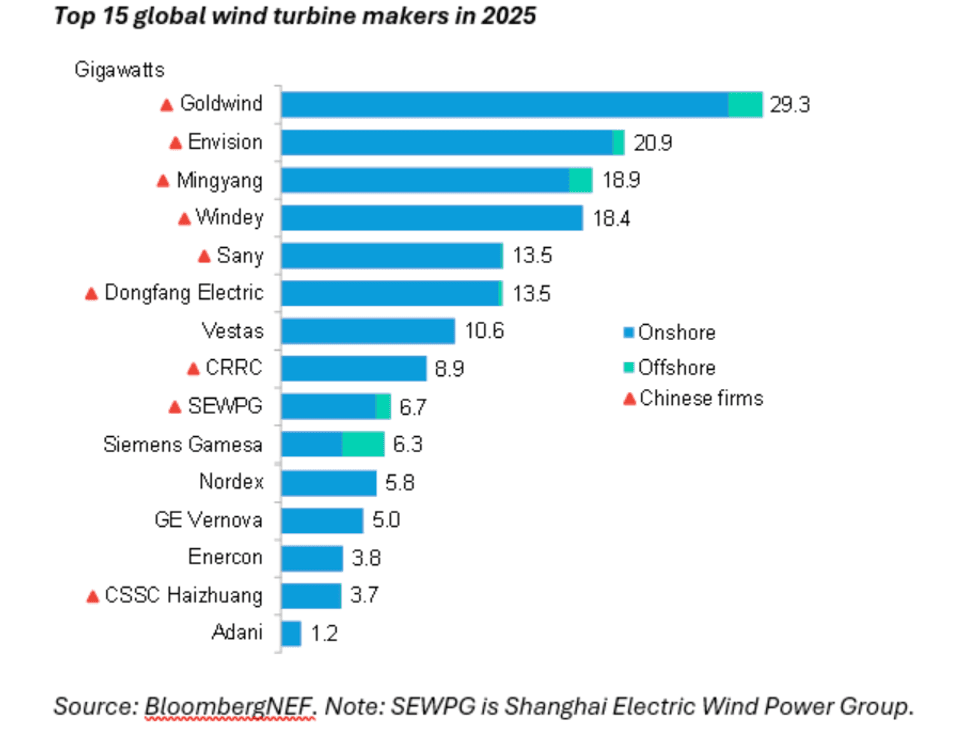

The global wind industry set a record last year, adding 169 gigawatts of turbines throughout 2025, according to the latest analysis from the consultancy BloombergNEF. The 38% surge compared to 2024 came as the momentum in the sector shifted to Asia. Chinese companies made up eight of the top 10 global wind turbine suppliers, the report found, as domestic installations in the People’s Republic reached an all-time high. India, meanwhile, edged out the U.S. and Germany as the world’s second largest market after China. Of all global wind additions, 161 gigawatts, or 95%, were onshore turbines, mostly spurred on by the domestic boom in China. Not only did that same building blitz help Beijing-based Goldwind hold onto its top spot as the world’s leading turbine supplier, it vaulted Chinese manufacturers into the next five slots in the global ranking. “Thanks to stable long-term policy support, wind installations over the past decade have become increasingly concentrated in mainland China,” Cristian Dinca, wind associate at BloombergNEF and lead author of the report, said in a statement. “Chinese manufacturers consistently top the global rankings. They benefitted particularly in 2025, as companies and provinces rushed to commission projects ahead of power market reforms and to meet targets set out in the Five Year Plan.”

Like in solar and batteries, the domestic boom in China is starting to spill over abroad. As Matthew wrote last year, Chinese manufacturers are making a big push into the European market.

Arizona’s utility regulator has repealed rules requiring electricity providers to generate at least 15% of their energy from renewables. Citing “dramatic” changes to the renewable energy landscape, the Arizona Corporation Commission said the cost to ratepayers of the rules adopted two decades ago was no longer justifiable, Utility Dive reported Monday. Since the rules first took effect in 2006, the utilities Arizona Public Services, Tucson Electric Power, and UniSource Energy Services “have collected more than $2.3 billion” in “surcharges from all customer classes to meet these mandates,” the regulator said in a press release following the March 4 ruling. “The mandates are no longer needed and the costs are no longer justified.”

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Reflect Orbital wants to launch 50,000 giant mirrors into space to bounce sunlight to the night side of the planet to power solar farms after sunset, provide lighting to rescue workers, and light city streets. Now, The New York Times reported Monday, the Hawthorne, California-based startup is asking the Federal Communications Commission for permission to send its first prototype satellite into space with a 60-foot-wide mirror. The company, which has raised more than $28 million from investors, could launch its test project as early as this summer. The public comment period on the FCC application closed yesterday. “We’re trying to build something that could replace fossil fuels and really power everything,” Ben Nowack, Reflect Orbital’s chief executive, told the newspaper.

It’s emblematic of the kind of audacious climate interventions on which investors are increasingly gambling. Last fall, Heatmap’s Robinson Meyer broke news that Stardust Solutions, a startup promising to artificially cool the planet by spraying aerosols into the atmosphere that reflect the sun’s light back into space, had raised $60 million to commercialize its technology. In December, Heatmap’s Katie Brigham had a scoop on the startup Overview Energy raising $20 million to build panels in space and beam solar power back down to Earth.

Emerald AI is a startup whose software Katie wrote last year “could save the grid” by helping data centers to ramp electricity usage up and down like a smart thermostat to allow more computing power to come online on the existing grid. InfraPartners is a company that designs, manufactures, and deploys prefabricated, modular data centers parts. You don’t need to be an expert in the data center industry’s energy problems to hear the wedding bells ringing. On Tuesday, the two companies announced a deal to partner on what they’re calling “flex-ready data centers,” a version of InfraPartners’ off the shelf computing hardware that comes equipped with Emerald AI’s software. “Building more infrastructure the way we have historically will not be fast enough. We need to make the infrastructure we have more intelligent by leveraging AI,” Bal Aujla, InfraPartners’ director of advanced research and engineering, said in a statement. “This partnership will turn data centers from grid constraints into grid partners and unlock more usable capacity from existing infrastructure. The result will be enhanced AI deployment without compromising reliability or sustainability.” Rather than rush to invest in big new power plants, Emerald AI chief scientist Ayse Coskun said making data centers flexible means “we can prudently expand our grid.”

War in Iran may be halting shipments of oil and liquified natural gas out of the Persian Gulf. But that isn’t stopping Chinese clean energy manufacturers from preparing to send shipments toward the war-torn region. Despite the conflict, the Jiangsu-based Shuangliang announced last week that it had delivered 80 megawatts of electrolyzers to a Chinese port for shipment to a 300-megawatt green hydrogen and ammonia plant in the special economic zone in Duqm, Oman. I know what you’re going to say: Oman’s status as the region’s Switzerland — a diplomatic powerhouse with a modern history of strategic neutrality in even the most heated geopolitical conflicts — means it isn’t a target for Iranian missiles. And there’s no guarantee the shipment will head there immediately. But it’s a sign of how determined China’s electrolyzer industry is to sell its hardware overseas amid inklings of a domestic slowdown.

Topsy turvy oil prices aren’t great for the U.S.

Oil prices are all over the place as markets reopened this week, climbing as high as $120 a barrel before crashing to around $85 after Donald Trump told CBS News that the war with Iran “is very complete, pretty much,” and that he was “thinking about taking it over,” referring to the Strait of Hormuz, the artery through which about a third of the world’s traded oil flows.

Even $85 is substantially higher than the $57 per barrel price from the end of last year. At that point, forecasters from both the public and the private sectors were expecting oil to stick around $60 a barrel through 2026.

Of course, crude oil itself is not something any consumer buys — but those high prices would likely feed through to higher consumer prices throughout the U.S. economy. That includes the price of gasoline, of course, which has risen by about $0.50 a gallon in the past month, according to AAA, — and jet fuel, which will mean increased travel costs. “Book your airfares now if they haven’t moved already,” Skanda Amarnath, the executive director of the economic policy think tank Employ America, told me.

High oil prices also raise the price of goods and services not directly linked to oil prices — groceries, for instance. “The cost of food, especially at the grocery store, is a function of the cost of diesel,” which fuels the trucks that get food to shelves, Amarnath told me. Diesel prices have risen even more than gasoline in the past week, by over $0.85 a gallon.

“We’ll see how long these prices stay elevated, how they feed their way through the supply chain and the value chain. But it’s clearly the case that it is a pretty adverse situation for both businesses and consumers.”

The oil market is going through one of the largest physical shocks in its modern history. Bloomberg’s Javier Blas estimates that of the 15 million barrels per day that regularly flow through the Strait of Hormuz, only about a third is getting through to the global market, whether through the strait itself or by alternative routes, such as the pipeline from Saudi Arabia’s eastern oil fields to the Red Sea.

Global daily oil production is just above 100 million barrels per day, meaning that around 10% of the oil supply on the market is stuck behind an effective blockade.

“The world is suddenly ‘short’ a volume that, in normal times, would dwarf almost any supply/demand imbalance we debate,” Morgan Stanley oil analyst Martjin Rats wrote in a note to clients on Sunday.

The fact that the U.S. is itself a leading producer and exporter of oil will only provide so much relief. Private sector economists have estimated that every $10 increase in the price of oil reduces economic growth somewhere between 0.1 and 0.2 percentage points.

“Petroleum product prices here in the U.S. tend to reflect global market conditions, so the price at the pump for gasoline and diesel reflect what’s going on with global prices,” Ben Cahill, a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told me. “What happens in the rest of the world still has a deep impact on U.S. energy prices.”

To the extent the U.S. economy benefits from its export capacity, the effects are likely localized to areas where oil production and export takes place, such as Texas and Louisiana. For the economy as a whole, higher oil prices will improve the “terms of trade,” essentially a measure of the value of imports a certain quantity of exports can “buy,” Ryan Cummings, chief of staff at Stanford Institute for Economic Policymaking, told me.

Could the U.S. oil industry ramp up production to capture those high prices and induce some relief?

Oil industry analysts, Heatmap founding executive editor Robinson Meyer, and the TV show Landman have all theorized that there is a “goldilocks” range of oil prices that are high enough to encourage exploration and production but not so high as to take out the economy as a whole. This range starts at around $60 or $70 on the low end and tops out at around $90 or $95. Above that, the economic damage from high prices would likely outweigh any benefit to drillers from expanded production.

And that’s if production were to expand at all.

“Capital discipline” has been the watchword of the U.S. oil and gas industry for years since the shale boom, meaning drillers are unlikely to chase price spikes by ramping up production heedlessly, CSIS’ Ben Cahill told me. “I think they’ll be quite cautious about doing that,” he said.

A test drive provided tantalizing evidence that a great, cheap EV is possible for the U.S.

Midway through the tortuous test drive over the mountains to Malibu, as the new Chevrolet Bolt EV ably zipped through a series of sharp canyon corners, I couldn’t help but think: Who would want to kill this car?

Such is life for the Bolt. Chevy revived the budget electric car after its fans howled when it killed the first version in 2023. But by the time the car press assembled last week for the official test drive of Bolt 2.0, the new car already had an expiration date: General Motors said it would end the production run next summer. This is a shame for a variety of reasons. Among the most important: The new Bolt, which starts just under $30,000 and is soon to start arriving at Chevy dealerships, shows that the cheap EV for the masses is really, almost there.

The 2027 Bolt comes with a 65 kilowatt-hour lithium iron phosphate battery that’s rated to deliver 262 miles of range. That’s not bad for an economy car, given that lots of more expensive EVs came with ranges in the low 200s just a couple of years ago.

Charging speed, the big bugaboo with the original Bolt, is fixed. The glacial 50-kilowatt speed has risen to 150 kilowatts, allowing the car to charge from 10% to 80% in about 25 minutes. That pales in comparison to the 350-kilowatt Hyundai touts for some of its EVs, but it makes the Bolt road trip an acceptable experience, not a slog. Crucially, the new Bolt comes with the NACS port and will seamlessly plug-and-charge at many charging stations, including Tesla’s.

Bolt comes with a single motor that delivers 210 horsepower and 169 pound-feet of torque — not eye-popping numbers. But because all of an electric car’s torque is available at any time, the Bolt feels livelier as it accelerates away from a start compared to an equivalent combustion-powered economy car. It huffs and puffs just a tad trying to accelerate uphill on California’s mountain highways, sure, but Bolt has enough oomph to have some fun without getting you into trouble. And in a world of white cars, Bolt comes in honest-to-goodness colors. Red. Blue. Yellow!

The tech features are the same story — that is, plenty good for the price. Many Bolt loyalists are incensed that Chevy killed off Apple Carplay and Android Auto integration in the new car, forcing drivers to rely on what’s built in. For those who can get over the disappointment, what is built into Bolt’s 11-inch touchscreen is pretty good, starting with Google Maps integration for navigation. Its method for displaying charging stations — and allowing the driver to filter them by plug style, provider, and other factors — isn’t quite up to the Silicon Valley seamlessness of a Rivian, but is easier to use than what a lot of legacy car companies put in their EVs. (The fabulous Kia EV9 three-row SUV I tested just before the Bolt is superior in just about every way except this.)

The Bolt even has a few features you wouldn’t expect at the entry level. The surround vision recorder for storing footage from the car’s camera is a first for a GM vehicle, Chevy says. The brand is also making a big to-do over the Super Cruise hands-free driving feature since the Bolt is now the least expensive car to get it, though adding all that tech takes the basic LT version of the Bolt up from $29,000 to more than $35,000, which is the starting price for the bigger Chevy Equinox EV.

With so much going right for this vehicle, why preemptively kill it? The most obvious factor is the Trump White House. Chevrolet had always called the Bolt’s return a limited run, but the fact that its production run might last for just a year and a half is a direct result of Trump tariffs: GM wants to make gas-powered Buick crossovers, currently made in China, at the Kansas factory that builds the Bolt.

And the loss last year of the federal incentive to buy an EV is particularly punitive for the Bolt. With $7,500 shaved off the price, the Chevy EV would have been cost-competitive with the cheapest new gas cars, like the Hyundai Elantra or Toyota Corolla. Without it, Bolt is closer in price to a larger vehicle like the Toyota RAV4. When Chevy can’t make the case that its EV is as cheap as any other small car you might be looking at, it must sell a car like Bolt on its down-the-road value: very little routine maintenance, no buying gasoline during a period of wartime oil shocks, and so on. That’s a tougher task, and perhaps explains why GM was so quick to move on.

Still, there’s clearly something bigger at stake here for GM. The American car companies’ pivot back to the short-term profitability of petroleum, exemplified by the Bolt-Buick affair, comes as the rest of the world continues to embrace EVs. Headlines lately have wondered whether China’s ascent combined with America’s yoyo-ing on electric power could lead to Detroit’s outright demise, leaving the U.S. auto industry with scraps as someone else’s superior EVs take over the world.

In this light, Chevy’s own market data on Bolt is especially jarring. Of the nearly 200,000 Bolts on the road from the car’s previous generation, 75% percent of those drivers came from other car companies to GM, and 72% remained loyal to GM. In other words, the new Bolt is set to build on General Motors’ status as the top EV-seller in America behind Tesla by expanding the established base of customers who love Chevy electric cars. That is what’s being tossed aside to increase quarterly profits.

Maybe the Bolt will surprise its maker, again. Even if a groundswell of enthusiasm for the new car isn’t enough to save it from extinction, perhaps it will prove to GM to give the budget EV yet another go-around when the market shifts yet again.