You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Talking to Google Geo’s vice president of sustainability, Yael Maguire.

While browsing Google Flights for an escape from the winter doldrums, I recently encountered a notification I hadn’t seen before. One particular return flight from Phoenix to New York was highlighted in light green as avoiding “as much CO2 as 1,400 trees absorb a day.”

I’d seen Google Flights’ emissions estimates before, of course — they’ve been around since 2021 — but this was the first time I’d seen it translate a number like “265 kg CO2e” into something I could actually understand. Suddenly, not picking the flight felt like it would have made me, well, kind of bad.

Yael Maguire, the vice president and general manager of the sustainability team at Google Geo — which includes Maps, Earth, and Project Sunroof, the company’s solar calculator — stressed that Google isn’t trying to take people’s agency away with these kinds of light-green guilt trips. “We want to make the sustainable choice the easy choice,” he told me, in reference to a slew of new tools the company has been rolling out, from fuel-efficient routing in Maps (which Google estimates has eliminated the emissions equivalent of 500,000 internal combustion cars from the road since 2021), to suggesting train routes to flight-shoppers, to nudging Europeans to ditch their cars when public transportation could get them to their destinations in a comparable amount of time.

Last week, I spoke to Maguire about the sustainability projects at Google Geo, including the team’s Solar API, which provides solar-planning data for millions of buildings worldwide. Our conversation has been lightly condensed for clarity and brevity.

Do you see your job at Google Geo as passively presenting sustainability information to users, or do you see it as actively nudging people toward making better choices for the planet?

We’re not trying to take agency away from anybody. We want to make sure — whether you’re a consumer choosing an eco-friendly route, or you’re a developer who’s thinking about trying to build more sustainably, or you’re a solar developer who wants to help with that — we want the choices to be in their hands. But we want to make it the easiest choice possible because, while it’s ultimately their decision, it will lead to carbon reductions over time.

That’s the idea behind fuel efficiency suggestions in Google Maps, where a route is prominently displayed with the little leaf, right?

Exactly. We launched a capability in Google Earth last year to help real estate developers do high-level planning and building development to make the sustainable choice the easy choice. As they’re saying, “We’re trying to get this many units with these kinds of amenities, etc., etc.,” we give them the tools to optimize for all the things they want to optimize for. But we can also say, “Hey, if you also care about sustainability, you can use different materials, we can get more sunlight in the area, and you have this much potential for solar.” And that just comes bundled with the tool itself.

We always try to find the co-benefits. I know for me personally, I always try to make the sustainable choice as much as I can. But I know that other people may not be as motivated by that, and having those co-benefits — like, it saves money, or it saves time, or it saves fuel, whatever it might be. We want to try to bring those together as much as possible.

When I was in Tbilisi, Georgia, a few months ago, I was using the ride-share app Bolt, and at the time it had a feature where if you tried to book a car to a location less than a 15-minute walk away, it would suggest you walk instead. I saw in a video from Google’s sustainability summit last fall that you’re rolling out something similar in some locations in Europe — France was one. Do you find these sorts of rollouts in the U.S. are stymied at all by how un-walkable most American cities are?

We are trying to make the most of cities as they are. They’re hard to change. But one of the things I find really encouraging is there’s definitely a long timeframe for this. Mayors and the folks in their departments of transportation recognize that they have to make more options available for people to commute and move around. They’re not necessarily going to be able to change things overnight. But there are major changes that are happening — for example, in the city of London, we were able to announce hundreds of miles of new bike lanes. So a lot of changes are happening over a relatively short amount of time, too.

Sometimes it’s hard to know what is going to be the impact of those decisions, though. And so, again, with these tools, city planners have the opportunity to scenario plan and say, “Okay, we’re thinking of trying to put bike lanes in this corridor in the city, what is going to be the impact on carbon?”

I wanted to ask a similar question in the context of a new feature that suggests train routes to Europeans looking for short-haul flights. How is Google thinking about promoting low-emissions transportation options like trains to Americans, eventually, when our infrastructure often isn’t there yet? Is this a challenge you talk about internally?

It is definitely something that is top of mind. But I do think even in the U.S., there are times when taking a train is actually faster. There are actually a lot of instances where walking, cycling, and public transportation are the most effective ways to get somewhere — and that’s not even considering the cost side of it, which is also something people might want to consider. I’m actually fairly optimistic — when I worked in San Francisco, I took public transportation, and I tried to walk as much as I can in all the cities that I’ve lived in, so I feel like I have lived experience in what the reality [in the U.S.] is. And some of these alternative options can be very effective. There’s more work to do, though, to make sure that we’re doing this globally.

Arguably, Google Maps could have a significant role to play in the success of the larger EV transition in terms of making charging stations and trip planning easy and handy for drivers. I’ve been working on planning my first EV road trip this summer and have been pretty intimidated, to be honest. Can you tell me what is in Google’s pipeline to help make this process easier for drivers?

I can’t talk about things that haven’t been announced yet, but I will say that, just as an overarching goal, we want to make that as easy as possible. I’m an EV owner, I have been for a number of years, and I know sometimes it can be a cognitive task to think about, “How am I going to charge and what is that experience going to be like?” So I would just say that we are really aware and trying to deeply understand the problem as much as possible, and our goal is to really address it.

Even when someone is thinking about purchasing a car, oftentimes people go to Google Search to look for vehicles, and we can help people understand what the potential is of a particular vehicle they’re considering. What typically concerns people is a long-distance trip. So we’ve made a tool where you can plug in a familiar destination — like for me, I live in San Francisco, it might be going to Tahoe— and for a given car you can see how many charges would you have to do on the way. Being able to make that info a little bit easier for people to see before they even buy the car is a thing that we’ve tried to do.

We’re also trying to make charging experiences as positive as possible. The first thing is, honestly, just getting as many chargers on the map as possible. There are a number of different providers who have charging infrastructure and sometimes all the data isn’t widely available so we’ve tried really, really hard to work with those partners. We have information on, I believe, 360,000 chargers worldwide and we’re constantly trying to grow that. On top of that — and I hope you don’t experience this — but not all the chargers work. You’ve probably seen on Google Maps, there are reviews, right? So there’s all kinds of work happening there.

My EV doesn’t have Google Maps integrated, unfortunately, but I’m really looking forward to one day having this feature where I can search for a charger along the route. We’d like to get to that point where you don’t actually have to do all this planning in advance and you can just get in your car and plan along the way like you would if it was another type of vehicle.

It’s one thing to have a tool like the Google Tree Canopy available for cities and organizers, and it’s another thing for people to actually use that tool and act on the information. How are you measuring your success?

We measure our success ultimately by what people do with our tools. So it’s not just about putting the tool out there. We actually try to understand what people are doing. In the case of what we did with eco-friendly routing, we worked with the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in the U.S., for example, to help validate our carbon emissions model. We’re going through that process for everything we do, whether it’s Project Sunroof or the Solar API, or other things like that.

You preempted my next question, but maybe you can talk about it in a more macro sense — Google has the goal of “collectively reducing 1 gigaton of carbon equivalent emissions annually by 2030” with tools like Solar API. Can you give me any sort of progress update?

This is a project that’s been going on for some time. We’ve been working with solar developers for a while, but we’ve been pleasantly surprised not only by the solar developer community engagement, but there’s actually other industries that have shown interest. So MyHEAT — they’re not a typical solar installer, but they’re finding this data really useful to go to cities and help them with the plans that they have.

So the gigaton goal itself, there is nothing to share now other than the progress on eco-friendly routing, but it is something that we hope we’ll be able to share progress on over time. But so far, we’re quite happy.

At a time when there’s a lot of nervousness around AI — and often for good reason — you’ve been pretty vocal in your excitement about how such tools can be used for the positive purposes of sustainability. Tell me why you’re an optimist.

Here’s why I’m an optimist: Because it’s where I put all of Google’s public goals in context. We talked about the gigaton goal, we talked about the Solar API — but I think this is also a question about energy usage and carbon intensity. We will continue to invest in the infrastructure that we need — and we need that infrastructure to be able to actually help solve some of these problems, by providing information to people — but at the same time, the company has been really focused on trying to minimize the carbon intensity of the energy we produce. So, since 2017, we’ve been operating off of 100% renewable energy; this is on an annualized basis. We also have an initiative to use carbon-free energy — so the source of the energy that ultimately goes where electrons are going to our data centers, we’re actively measuring what percentage of that is carbon-free on a 24/7 basis.

With our net-zero commitments, to be on a net basis by 2030, that includes all of our AI infrastructure. That’s where I would try to separate the energy use that’s required to operate AI from the carbon intensity, which I think is very different. Our data centers, we estimate, are one-and-a-half times more efficient than your average data center. And with AI workloads themselves, in some instances, we’ve been able to get the energy usage down by 100x, and the corresponding amount of carbon intensity down by 1,000x.

But to your point, at the same time, it is very much on our minds that the carbon intensity to run all of these AI workloads — how does that compare to the benefits that they’re able to provide? I think that’s where I am. I do have a lot of optimism about the efficiency work, about the trajectory of carbon-free energy and net zero. The upsides in terms of what it does for solar, what it does for transportation — yeah, I am a big believer.

The big reason why I’m so excited about this opportunity in the Maps and Geo space is I just think there’s so much opportunity for all kinds of organizations, including individual citizens, to make these choices and changes to their environment. And I think the role that AI has is enormous — obviously not the whole thing, because it doesn’t build cycling lanes. People have to go do that. People have to change policies around how buildings are going to have less carbon intensity when they’re built. There’s tons and tons of other work that is required to actually build the future that we want, that is lower carbon intensity — ideally zero. But I do think that AI plays an enormous role as decision support for all those choices that are needed in the future.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Boosters say that the energy demand from data centers make VPPs a necessary tool, but big challenges still remain.

The story of electricity in the modern economy is one of large, centralized generation sources — fossil-fuel power plants, solar farms, nuclear reactors, and the like. But devices in our homes, yards, and driveways — from smart thermostats to electric vehicles and air-source heat pumps — can also act as mini-power plants or adjust a home’s energy usage in real time. Link thousands of these resources together to respond to spikes in energy demand or shift electricity load to off-peak hours, and you’ve got what the industry calls a virtual power plant, or VPP.

The theoretical potential of VPPs to maximize the use of existing energy infrastructure — thereby reducing the need to build additional poles, wires, and power plants — has long been recognized. But there are significant coordination challenges between equipment manufacturers, software platforms, and grid operators that have made them both impractical and impracticable. Electricity markets weren’t designed for individual consumers to function as localized power producers. The VPP model also often conflicts with utility incentives that favor infrastructure investments. And some say it would be simpler and more equitable for utilities to build their own battery storage systems to serve the grid directly.

Now, however, many experts say that VPPs’ time to shine is nigh. Homeowners are increasingly pairing rooftop solar with home batteries, installing electric heat pumps, and buying EVs — effectively large batteries on wheels. At the same time, the ongoing data center buildout has pushed electricity demand growth upward for the first time in decades, leaving the industry hungry for new sources of cheap, clean, and quickly deployable power.

“VPPs have been waiting for a crisis and cash to scale and meet the moment. And now we have both,” Mark Dyson, a managing director at RMI, a clean energy think tank, told me. “We have a load growth crisis, and we have a class of customers who have a very high willingness to pay for power as quickly as possible.” Those customers are the data center hyperscalers, of course, who are impatient to circumvent the lengthy grid interconnection queue in any way possible, potentially even by subsidizing VPP programs themselves.

Jigar Shah, former director of the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office under President Biden, is a major VPP booster, calling their scale-up “the fastest and most cost-effective way to support electrification” in a 2024 DOE release announcing a partnership to integrate VPPs onto the electric grid. While VPPs today provide roughly 37.5 gigawatts of flexible capacity, Shah’s goal was to scale that to between 80 and160 gigawatts by 2030. That’s equivalent to around 7% to 13% of the U.S.’s current utility-scale electricity generating capacity.

Utilities are infamously slow to adopt new technologies. But Apoorv Bhargava, CEO and co-founder of the utility-focused VPP software platform WeaveGrid, told me that he’s “felt a sea change in how aware utilities are that, building my way out is not going to happen; burning my way out is not going to happen.” That’s led, he explained, to an industry-wide recognition that “we need to get much better at flexing resources — whether that’s consumer resources, whether that’s utility-cited resources, whether that’s hyperscalers even. We’ve got to flex.”

Actual VPP capacity appears to have grown more slowly over the past few years than the enthusiasm surrounding the resource’s potential. According to renewable energy consultancy WoodMackenzie, while the number of new VPP programs, offtakers, and company deployments each grew over 33% last year, capacity grew by a more modest 13.7%. Ben Hertz-Shargel, who leads a WoodMac research team focused on distributed energy resources, attributed this slower growth to utility pilot programs that cap VPP participation, rules that limit financial incentives by restricting how VPP capacity is credited, and other market barriers that make it difficult for customers to engage.

Dyson similarly said he sees “friction on the utility side, on the regulatory side, to align the incentive programs with real needs.” These points of friction include requirements for all participating devices to communicate real-time performance data — even for minor, easily modeled metrics such as a smart thermostat’s output — as well as utilities’ hesitancy to share household-level metering data with third parties, even when it’s necessary to enroll in a VPP program. Figuring out new norms for utilities and state regulations is “the nut that we have to crack,” he said.

One of the more befuddling aspects of the whole VPP ecosystem, however, can be just trying to parse out what services a VPP program can actually provide. The term VPP can refer to anything from decades-old demand response programs that have customers manually shutting off appliances during periods of grid stress to aspirational, fully integrated systems that continually and automatically respond to the grid’s needs.

“When a customer like a utility says, I want to do a VPP, nobody knows what they’re talking about. And when a regulator says we should enable VPPs, nobody knows what services they’re selling,” Bhargava told me.

In an effort to help clarify things, the software company EnergyHub developed what it calls the VPP Maturity Model, which defines five levels of maturity. Level 0 represents basic demand response. A utility might call up an industrial customer and tell them to reduce their load, or use price signals to encourage households to cut down on electricity use in the evening. Level 1 incorporates smart devices that can send data back to the utility, while at Level 2, VPPs can more precisely ramp load up or down over a period of hours with better monitoring, forecasting, and some partial autonomy — this is where most advanced VPPs are at today.

Moving into Levels 3 and 4 involves more automation, the ability to handle extended grid events, and ultimately full integration with the utility and grid-operator’s systems to provide 24/7 value. The ultimate goal, according to EnergyHub’s model, is for VPPs to operate indistinguishably from conventional power plants, eventually surpassing them in capabilities.

But some question whether imitating such a fundamentally different resource should actually be the end game.

“What we don’t need is a bunch of virtual power plants that are overconstrained to act just like gas plants,” Dyson told me. By trying to engineer “a new technology to behave like an old technology,” he said, grid operators risk overlooking the unique value VPPs can provide — particularly on the distribution grid, which delivers electricity directly to homes and businesses. Here, VPPs can help manage voltage regulation or work to avoid overloads on lines with many distributed resources, such as solar panels — things traditional power plants can’t do because they’re not connected to these local lines.

Still others are frankly dubious of the value of large-scale VPP programs in the first place. “The benefits of virtual power plants, they look really tantalizing on paper,” Ryan Hanna, a research scientist at UC San Diego’s Center for Energy Research told me. “Ultimately, they’re providing electric services to the electric power grid that the power grid needs. But other resources could equally provide those.”

Why not, he posited, just incentivize or require utilities to incorporate battery storage systems at either the transmission or distribution levels into their long-term plans for meeting demand? Large-scale batteries would also help utilities maximize the value of their existing assets and capture many of the other benefits VPPs promise. Plus, they would do it at a “larger size, and therefore a lower unit cost,” Hanna told me.

Many VPP companies would certainly dispute the cost argument, and also note that with grid interconnection queues stretching on for years, VPPs offer a way to deploy aggregated resources far more quickly than building out and connecting new, centralized assets.

But another advantage of Hanna’s utility-led approach, he said, is that the benefits would be shared equally — all customers would see similar savings on their electricity bills as grid-scale batteries mitigate the need for expensive new infrastructure, the cost of which is typically passed on to ratepayers. VPPs, on the other hand, deliver an outsize benefit to the customers incentivized to participate by dint of their neighborhood’s specific needs, and with the cash on hand to invest in resources such as a home battery or an EV.

This echoes a familiar equity argument made about rooftop solar: that the financial benefits accrue only to households that can afford the upfront investment, while the cost of maintaining shared grid infrastructure falls more heavily on non-participants. Except in the case of VPPs, non-participants also stand to benefit — just less — if the programs succeed in driving down system costs and improving grid reliability.

“I may pay Customer A and Customer B may sit on the sidelines,” Matthew Plante, co-founder and president of the VPP operator Voltus, told me. “Customer A gets a direct payment, but customer B’s rates go down. And so everyone benefits, even if not directly.” On the flip side, if the VPP didn’t exist, that would be a lose-lose for all customers.

Plante is certainly not opposed to the idea of utilities building grid-scale batteries themselves, though. Neither he nor anyone else can afford to be picky about the way new capacity comes online right now, he said. “I think we all want to say, what is quickest and most efficient and most economical? And let’s choose that solution. Sometimes it’s got to be both.”

For its part, Voltus is betting that its pathway to scale runs through its recently announced partnership with the U.S. division of Octopus Energy, the U.K.’s largest energy supplier, which provides software to utilities to coordinate distributed energy resources and enroll customers in VPP programs. Together, they plan to build portfolios of flexible capacity for utilities and wholesale electricity markets, areas where Octopus has extensive experience. “So that gives us market access in a much quicker way,” Plante told me.”

At this moment, there’s no customer more motivated than a data center to bring large volumes of clean energy online as quickly as possible, in whatever way possible. Because while data enters themselves can theoretically act as flexible loads, ramping up and down in response to grid conditions, operators would probably rather pay others to be flexible instead.

“Does a data center company ever want to say, okay, I won’t run my training model for a couple hours on the hottest day of the year? They don’t, because it’s worth a lot of money to run that training model 24/7,” Dyson told me. “Instead, the opportunity here is to use the money that generates to pay other people to flex their load, or pay other people to adopt batteries or other resources that can help create headroom on the system.”

Both Plante of Voltus and Bhargava of WeaveGrid confirmed that hyperscalers are excited by the idea of subsidizing VPP programs in one form or another. That could look like providing capital to help customers in a data center’s service territory buy residential batteries or contracts that guarantee a return for VPP aggregators like Voltus. “I think they recognize in us an ability to get capacity unlocked quickly,” Plante told me.

Yet another knot in this whole equation, however, is that even given hyperscalers’ enthusiasm and the maturation of VPP technology, most utilities still lack a natural incentive to support this resource. That’s because investor-owned utilities — which serve approximately 70% of U.S. electricity customers — earn profits primarily by building infrastructure such as power plants and transmission lines, receiving a guaranteed rate of return on that capital investment. Successful VPPs, on the other hand, reduce a utility’s need to build new assets.

The industry is well aware of this fundamental disconnect, though some contend that current load growth ought to quell this concern. Utilities will still need to build significant new infrastructure to meet the moment, Bhargava told me, and are now under intense pressure to expand the grid’s capacity in other ways, as well.

“They cannot build fast enough. There’s not enough copper, there’s not enough transformers, there’s not enough people,” Bhargava explained. VPPs, he expects, will allow utilities to better prioritize infrastructure upgrades that stand to be most impactful, such as building a substation near a data center instead of in a suburb that could be adequately served by distributed resources.

The real question he sees now is, “How do we make our flexibility as good as copper? How do we make people trust in it as much as they would trust in upgrading the system?”

On the real copper gap, Illinois’ atomic mojo, and offshore headwinds

Current conditions: The deadliest avalanche in modern California history killed at least eight skiers near Lake Tahoe • Strong winds are raising the wildfire risk across vast swaths of the northern Plains, from Montana to the Dakotas, and the Southwest, especially New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma • Nairobi is bracing for days more of rain as the Kenyan capital battles severe flooding.

Last week, the Environmental Protection Agency repealed the “endangerment finding” that undergirds all federal greenhouse gas regulations, effectively eliminating the justification for curbs on carbon dioxide from tailpipes or smokestacks. That was great news for the nation’s shrinking fleet of coal-fired power plants. Now there’s even more help on the way from the Trump administration. The agency plans to curb rules on how much hazard pollutants, including mercury, coal plants are allowed to emit, The New York Times reported Wednesday, citing leaked internal documents. Senior EPA officials are reportedly expected to announce the regulatory change during a trip to Louisville, Kentucky on Friday. While coal plant owners will no doubt welcome less restrictive regulations, the effort may not do much to keep some of the nation’s dirtiest stations running. Despite the Trump administration’s orders to keep coal generators open past retirement, as Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote in November, the plants keep breaking down.

At the same time, the blowback to the so-called climate killshot the EPA took by rescinding the endangerment finding has just begun. Environmental groups just filed a lawsuit challenging the agency’s interpretation of the Clean Air Act to cover only the effects of regional pollution, not global emissions, according to Landmark, a newsletter tracking climate litigation.

Copper prices — as readers of this newsletter are surely well aware — are booming as demand for the metal needed for virtually every electrical application skyrockets. Just last month, Amazon inked a deal with Rio Tinto to buy America’s first new copper output for its data center buildout. But new research from a leading mineral supply chain analyst suggests the U.S. can meet 145% of its annual demand using raw copper from overseas and domestic mines and from scrap. By contrast, China — the world’s largest consumer — can source just 40% of its copper that way. What the U.S. lacks, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, is the downstream processing capacity to turn raw copper into the copper cathode manufacturers need. “The U.S. is producing more copper than it uses, and is far more self-reliant than China in terms of raw materials,” Benchmark analyst Albert Mackenzie told the Financial Times. The research calls into question the Trump administration’s mineral policy, which includes stockpiling copper from jointly-owned ventures in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and domestically. “Stockpiling metal ores doesn’t help if you don’t have midstream processing,” Stephen Empedocles, chief executive of US lobbying firm Clark Street Associates, told the newspaper.

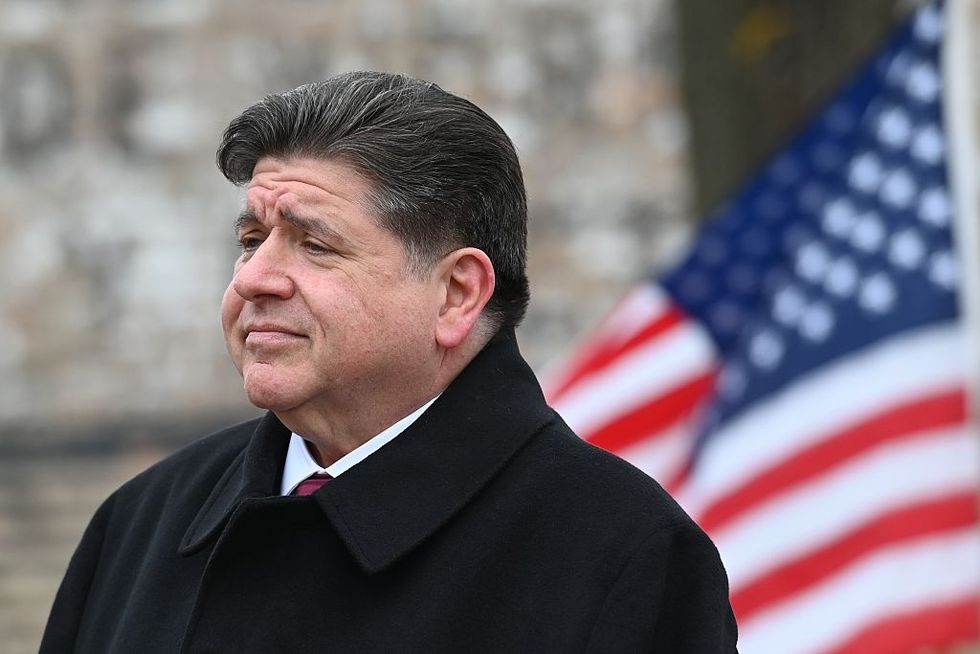

Illinois generates more of its power from nuclear energy than any other state. Yet for years the state has banned construction of new reactors. Governor JB Pritzker, a Democrat, partially lifted the prohibition in 2023, allowing for development of as-yet-nonexistent small modular reactors. With excitement about deploying large reactors with time-tested designs now building, Pritzker last month signed legislation fully repealing the ban. In his state of the state address on Wednesday, the governor listed the expansion of atomic energy among his administration’s top priorities. “Illinois is already No. 1 in clean nuclear energy production,” he said. “That is a leadership mantle that we must hold onto.” Shortly afterward, he issued an executive order directing state agencies to help speed up siting and construction of new reactors. Asked what he thought of the governor’s move, Emmet Penney, a native Chicagoan and nuclear expert at the right-leaning Foundation for American Innovation, told me the state’s nuclear lead is “an advantage that Pritzker wisely wants to maintain.” He pointed out that the policy change seems to be copying New York Governor Kathy Hochul’s playbook. “The governor’s nuclear leadership in the Land of Lincoln — first repealing the moratorium and now this Hochul-inspired executive order — signal that the nuclear renaissance is a new bipartisan commitment.”

The U.S. is even taking an interest in building nuclear reactors in the nation that, until 1946, was the nascent American empire’s largest overseas territory. The Philippines built an American-made nuclear reactor in the 1980s, but abandoned the single-reactor project on the Bataan peninsula after the Chernobyl accident and the fall of the Ferdinand Marcos dictatorship that considered the plant a key state project. For years now, there’s been a growing push in Manila to meet the country’s soaring electricity needs by restarting work on the plant or building new reactors. But Washington has largely ignored those efforts, even as the Russians, Canadians, and Koreans eyed taking on the project. Now the Trump administration is lending its hand for deploying small modular reactors. The U.S. Trade and Development Agency just announced funding to help the utility MGEN conduct a technical review of U.S. SMR designs, NucNet reported Wednesday.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Despite the American government’s crusade against the sector, Europe is going all in on offshore wind. For a glimpse of what an industry not thrust into legal turmoil by the federal government looks like, consider that just on Wednesday the homepage of the trade publication OffshoreWIND.biz featured stories about major advancements on at least three projects totaling nearly 5 gigawatts:

That’s not to say everything is — forgive me — breezy for the industry. Germany currently gives renewables priority when connecting to the grid, but a new draft law would give grid operators more discretion when it comes to offshore wind, according to a leaked document seen by Windpower Monthly.

American clean energy manufacturing is in retreat as the Trump administration’s attacks on consumer incentives have forced companies to reorient their strategies. But there is at least one company setting up its factories in the U.S. The sodium-ion battery startup Syntropic Power announced plans to build 2 gigawatts of storage projects in 2026. While the North Carolina-based company “does not reveal where it manufactures its battery systems,” Solar Power World reported, it “does say” it’s establishing manufacturing capacity in the U.S. “We’re making this move now because the U.S. market needs storage that can be deployed with confidence, supported by certification, insurance acceptance, and a secure domestic supply chain,” said Phillip Martin, Syntropic’s chief executive.

For years now, U.S. manufacturers have touted sodium-ion batteries as the next big thing, given that the minerals needed to store energy are more abundant and don’t afford China the same supply-chain advantage that lithium-ion packs do. But as my colleague Katie Brigham covered last April, it’s been difficult building a business around dethroning lithium. New entrants are trying proprietary chemistries to avoid the mistakes other companies made, as Katie wrote in October when the startup Alsym launched a new stationary battery product.

Last spring, Heron Power, the next-generation transformer manufacturer led by a former Tesla executive, raised $38 million in a Series A round. Weeks later, Spain’s entire grid collapsed from voltage fluctuations spurred by a shortage of thermal power and not enough inverters to handle the country’s vast output of solar power — the exact kind of problem Heron Power’s equipment is meant to solve. That real-life evidence, coupled with the general boom in electrical equipment, has clearly helped the sales pitch. On Wednesday, the company closed a $140 million Series B round co-led by the venture giants Andreessen Horowitz and Breakthrough Energy Ventures. “We need new, more capable solutions to keep pace with accelerating energy demand and the rapid growth of gigascale compute,” Drew Baglino, Heron’s founder and chief executive, said in a statement. “Too much of today’s electrical infrastructure is passive, clunky equipment designed decades ago. At Heron we are manifesting an alternative future, where modern power electronics enable projects to come online faster, the grid to operate more reliably, and scale affordably.”

A senior scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy on what Trump has lost by dismantling Biden’s energy resilience strategy.

A fossil fuel superpower cannot sustain deep emissions reductions if doing so drives up costs for vulnerable consumers, undercuts strategic domestic industries, or threatens the survival of communities that depend on fossil fuel production. That makes America’s climate problem an economic problem.

Or at least that was the theory behind Biden-era climate policy. The agenda embedded in major legislation — including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act — combined direct emissions-reduction tools like clean energy tax credits with a broader set of policies aimed at reshaping the U.S. economy to support long-term decarbonization. At a minimum, this mix of emissions-reducing and transformation-inducing policies promised a valuable test of political economy: whether sustained investments in both clean energy industries and in the most vulnerable households and communities could help build the economic and institutional foundations for a faster and less disruptive energy transition.

Sweeping policy reversals have cut these efforts short. Abandoning the strategy makes the U.S. economy less resilient to the decline of fossil fuels. It also risks sowing distrust among communities and firms that were poised to benefit, complicating future efforts to recommit to the economic policies needed to sustain an energy transition.

This agenda rested on the idea that sustaining decarbonization would require structural changes across the economy, not just cleaner sources of energy. First, in a country that derives substantial economic and geopolitical power from carbon-intensive industries, a durable energy transition would require the United States to become a clean energy superpower in its own right. Only then could the domestic economy plausibly gain, rather than lose, from a shift away from fossil fuels.

Second, with millions of households struggling to afford basic energy services and fossil fuels often providing relatively cheap energy, climate policy would need to ensure that clean energy deployment reduces household energy burdens rather than exacerbates them.

Third, policies would need to strengthen the economic resilience of communities that rely heavily on fossil fuel industries so the energy transition does not translate into shrinking tax bases, school closures, and lost economic opportunity in places that have powered the country for generations.

This strategy to reshape the economy for the energy transition has largely been dismantled under President Trump.

My recent research examines federal support for fossil fuel-reliant communities, assessing President Biden’s stated goal of “revitalizing the economies of coal, oil, gas, and power plant communities.” Federal spending data provides little evidence that these at-risk communities have been effectively targeted. One reason is timing: While legislation authorized unprecedented support, actual disbursements lagged far behind those commitments.

Many of the key policies — including $4 billion in manufacturing tax credits reserved for communities affected by coal closures — took years to move from statutory language to implementation guidance and final project selection. As a result, aside from certain pandemic-era programs, fossil fuel-reliant communities had received limited support by the time Trump took office last year.

Since then, the Trump administration and Congress have canceled projects intended to benefit fossil fuel-reliant regions, including carbon capture and clean hydrogen demonstrations, and discontinued programs designed to help communities access and implement federal funding.

Other elements of the strategy to reduce the country’s vulnerability to fossil fuel decline have fared even worse under the Trump administration. Programs intended to help households access and afford clean energy — most notably the $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund — were effectively canceled last year, including attempts to claw back previously awarded funds. More broadly, the rollback of IRA programs with an explicit equity or justice focus leaves lower-income households more exposed to the economic disruptions that can accompany an energy transition.

By contrast, subsidies and grant programs aimed at strengthening the country’s energy manufacturing base have largely survived, including tax credits supporting domestic production of batteries, solar components, and other key technologies. Even so, the investment environment has weakened. Automakers have scaled back planned U.S. battery manufacturing expansions. Clean Investment Monitor data shows annual clean energy manufacturing investments on pace to decline in 2025, after rising sharply from 2022 to 2024. Whatever one believed about the potential to build globally competitive domestic supply chains for the technologies that will power clean energy systems, those prospects have dimmed amid slowing investment and the Trump administration’s prioritization of fossil fuels.

Perhaps these outcomes were unavoidable. Building a strong domestic solar industry was always uncertain, and place-based economic development programs have a mixed track record even under favorable conditions. Still, the Biden-era approach reflected a coherent theory of climate politics that warranted a real-world test.

Over the past year, debates in climate policy circles have centered on whether clean energy progress can continue under less supportive federal policies, with plausible cases made on both sides. The fate of Biden’s broader economic strategy to sustain the energy transition, however, is less ambiguous. The underlying dependence of the United States on fossil fuels across industries, households, and many local communities remains largely unchanged.