You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Is international cooperation or technological development the answer to an apocalyptic threat?

Christopher Nolan’s film Oppenheimer is about the great military contest of the Second World War, but only in the background. It’s really about a clash of visions for a postwar world defined by the physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer’s work at Los Alamos and beyond. The great power unleashed by the bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki could be dwarfed by what knowledge of nuclear physics could produce in the coming years, risking a war more horrifying than the one that had just concluded.

Oppenheimer, and many of his fellow atomic scientists, would spend much of the postwar period arguing for international cooperation, scientific openness, and nuclear restriction. But there was another cadre of scientists, exemplified by a former colleague turned rival, Edward Teller, that sought to answer the threat of nuclear annihilation with new technology — including even bigger bombs.

As the urgency of the nuclear question declined with the end of the Cold War, the scientific community took up a new threat to global civilization: climate change. While the conflict mapped out in Oppenheimer was over nuclear weapons, the clash of visions, which ended up burying Oppenheimer and elevating Teller, also maps out to the great debate over global warming: Should we reach international agreements to cooperatively reduce carbon emissions or should we throw our — and specifically America’s — great resources into a headlong rush of technological development? Should we massively overhaul our energy system or make the sun a little less bright?

Oppenheimer’s dream of international cooperation to prevent a nuclear arms race was born even before the Manhattan Project culminated with the Trinity test. Oppenheimer and Danish physicist Niels Bohr “believed that an agreement between the wartime allies based upon the sharing of information, including the existence of the Manhattan Project, could prevent the surfacing of a nuclear-armed world,” writes Marco Borghi in a Wilson Institute working paper.

Oppenheimer even suggested that the Soviets be informed of the Manhattan Project’s efforts and, according to Martin Sherwin and Kai Bird’s American Prometheus, had “assumed that such forthright discussions were taking place at that very moment” at the conference in Potsdam where, Oppenheimer “was later appalled to learn” that Harry Truman had only vaguely mentioned the bomb to Joseph Stalin, scotching the first opportunity for international nuclear cooperation.

Oppenheimer continued to take up the cause of international cooperation, working as the lead advisor for Dean Acheson and David Lilienthal on their 1946 nuclear control proposal, which would never get accepted by the United Nations and, namely, the Soviet Union after it was amended by Truman’s appointed U.N. representative Bernard Baruch to be more favorable to the United States.

In view of the next 50 years of nuclear history — further proliferation, the development of thermonuclear weapons that could be mounted on missiles that were likely impossible to shoot down — the proposals Oppenheimer developed seem utopian: The U.N. would "bring under its complete control world supplies of uranium and thorium," including all mining, and would control all nuclear reactors. This scheme would also make the construction of new weapons impossible, lest other nations build their own.

By the end of 1946, the Baruch proposal had died along with any prospect of international control of nuclear power, all the while the Soviets were working intensely to disrupt America’s nuclear monopoly — with the help of information ferried out of Los Alamos — by successfully testing a weapon before the end of the decade.

With the failure of international arms control and the beginning of the arms race, Oppenheimer’s vision of a post-Trinity world would come to shambles. For Teller, however, it was a great opportunity.

While Oppenheimer planned to stave off nuclear annihilation through international cooperation, Teller was trying to build a bigger deterrent.

Since the early stages of the Manhattan Project, Teller had been dreaming of a fusion weapon many times more powerful than the first atomic bombs, what was then called the “Super.” When the atomic bomb was completed, he would again push for the creation of a thermonuclear bomb, but the efforts stalled thanks to technical and theoretical issues with Teller’s proposed design.

Nolan captures Teller’s early comprehension of just how powerful nuclear weapons can be. In a scene that’s pulled straight from accounts of the Trinity blast, most of the scientists who view the test are either in bunkers wearing welding goggles or following instructions to lie down, facing away from the blast. Not so for Teller. He lathers sunscreen on his face, straps on a pair of dark goggles, and views the explosion straight on, even pursing his lips as the explosion lights up the desert night brighter than the sun.

And it was that power — the sun’s — that Teller wanted to harness in pursuit of his “Super,” where a bomb’s power would be derived from fusing together hydrogen atoms, creating helium — and a great deal of energy. It would even use a fission bomb to help ignite the process.

Oppenheimer and several scientific luminaries, including Manhattan Project scientists Enrico Fermi and Isidor Rabi, opposed the bomb, issuing in their official report on their positions advising the Atomic Energy Commission in 1949 statements that the hydrogen bomb was infeasible, strategically useless, and potentially a weapon of “genocide.”

But by 1950, thanks in part to Teller and the advocacy of Lewis Strauss, a financier turned government official and the approximate villain of Nolan’s film, Harry Truman would sign off on a hydrogen bomb project, resulting in the 1952 “Ivy Mike” test where a bomb using a design from Teller and mathematician Stan Ulam would vaporize the Pacific Island Elugelab with a blast about 700 times more powerful than the one that destroyed Hiroshima.

The success of the project re-ignited doubts around Oppenheimer’s well-known left-wing political associations in the years before the war and, thanks to scheming by Strauss, he was denied a renewed security clearance.

While several Manhattan Project scientists testified on his behalf, Teller did not, saying, “I thoroughly disagreed with him in numerous issues and his actions frankly appeared to me confused and complicated.”

It was the end of Oppenheimer’s public career. The New Deal Democrat had been eclipsed by Teller, who would become the scientific avatar of the Reagan Republicans.

For the next few decades, Teller would stay close to politicians, the military, and the media, exercising a great deal of influence over arms policy for several decades from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, which he helped found, and his academic perch at the University of California.

He pooh-poohed the dangers of radiation, supported the building of more and bigger bombs that could be delivered by longer and longer range missiles, and opposed prohibitions on testing. When Dwight Eisenhower was considering a negotiated nuclear test ban, Teller faced off against future Nobel laureate and Manhattan Project alumnus Hans Bethe over whether nuclear tests could be hidden from detection by conducting them underground in a massive hole; the eventual 1963 test ban treaty would exempt underground testing.

As the Cold War settled into a nuclear standoff with both the United States and the Soviet Union possessing enough missiles and nuclear weapons to wipe out the other, Teller didn’t look to treaties, limitations, and cooperation to solve the problem of nuclear brinksmanship, but instead to space: He wanted to neutralize the threat of a Soviet first strike using x-ray lasers from space powered by nuclear explosions (he was again opposed by Bethe and the x-ray lasers never came to fruition).

He also notoriously dreamed up Project Plowshare, the civilian nuclear project which would get close to nuking out a new harbor in Northern Alaska and actually did attempt to extract gas in New Mexico and Colorado using nuclear explosions.

Yet, in perhaps the strangest turn of all, Teller also became something of a key figure in the history of climate change research, both in his relatively early awareness of the problem and the conceptual gigantism he brought to proposing to solve it.

While publicly skeptical of climate change later in his life, Teller was starting to think about climate change, decades before James Hansen’s seminal 1988 Congressional testimony.

The researcher and climate litigator Benajmin Franta made the startling archival discovery that Teller had given a speech at an oil industry event in 1959 where he warned “energy resources will run short as we use more and more of the fossil fuels,” and, after explaining the greenhouse effect, he said that “it has been calculated that a temperature rise corresponding to a 10 percent increase in carbon dioxide will be sufficient to melt the icecap and submerge New York … I think that this chemical contamination is more serious than most people tend to believe.”

Teller was also engaged with issues around energy and other “peaceful” uses of nuclear power. In response to concerns about the dangers of nuclear reactors, he in the 1960s began advocating putting them underground, and by the early 1990s proposed running said underground nuclear reactors automatically in order to avoid the human error he blamed for the disasters at Chernobyl and Three Mile Island.

While Teller was always happy to find some collaborators to almost throw off an ingenious-if-extreme solution to a problem, there is a strain of “Tellerism,” both institutionally and conceptually, that persists to this day in climate science and energy policy.

Nuclear science and climate science had long been intertwined, Stanford historian Paul Edwards writes, including that the “earliest global climate models relied on numerical methods very similar to those developed by nuclear weapons designers for solving the fluid dynamics equations needed to analyze shock waves produced in nuclear explosions.”

Where Teller comes in is in the role that Lawrence Livermore played in both its energy research and climate modeling. “With the Cold War over and research on nuclear weapons in decline, the national laboratories faced a quandary: What would justify their continued existence?” Edwards writes. The answer in many cases would be climate change, due to these labs’ ample collection of computing power, “expertise in numerical modeling of fluid dynamics, and their skills in managing very large data sets.”

One of those labs was Livermore, the institution founded by Teller, a leading center of climate and energy modeling and research since the late 1980s. “[Teller] was very enthusiastic about weather control,” early climate modeler Cecil “Chuck” Leith told Edwards in an oral history.

The Department of Energy writ large, which inherited much of the responsibilities of the Atomic Energy Commission, is now one of the lead agencies on climate change policy and energy research.

Which brings us to fusion.

It was Teller’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory that earlier this year successfully got more power out of a controlled fusion reaction than it put in — and it was Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm who announced it, calling it the “holy grail” of clean energy development.

Teller’s journey with fusion is familiar to its history: early cautious optimism followed by a realization that it would likely not be achieved soon. As early as 1958, he said in a speech that he had been discussing “controlled fusion” at Los Alamos and that “thermonuclear energy generation is possible,” although he admitted that “the problem is not quite easy” and by 1987 had given up on seeing it realized during his lifetime.

Still, what controlled fusion we do have at Livermore’s National Ignition Facility owes something to Teller and the technology he pioneered in the hydrogen bomb, according to physicist NJ Fisch.

While fusion is one infamous technological fix for the problem of clean and cheap energy production, Teller and the Livermore cadres were also a major influence on the development of solar geoengineering, the idea that global warming could be averted not by reducing the emissions of greenhouse gas into the atmosphere, but by making the sun less intense.

In a mildly trolling column for the Wall Street Journal in January 1998, Teller professed agnosticism on climate change (despite giving that speech to oil executives three decades prior) but proposed an alternative policy that would be “far less burdensome than even a system of market-allocated emissions permits”: solar geoengineering with “fine particles.”

The op-ed placed in the conservative pages of the Wall Street Journal was almost certainly an effort to oppose the recently signed Kyoto Protocol, but the ideas have persisted among thinkers and scientists whose engagement with environmental issues went far beyond their own opinion about Al Gore and by extension the environmental movement as a whole (Teller’s feelings about both were negative).

But his proposal would be familiar to the climate debates of today: particle emissions that would scatter sunlight and thus lower atmospheric temperatures. If climate change had to be addressed, Teller argued, “let us play to our uniquely American strengths in innovation and technology to offset any global warming by the least costly means possible.”

A paper he wrote with two colleagues that was an early call for spraying sulfates in the stratosphere also proposed “deploying electrically-conducting sheeting, either in the stratosphere or in low Earth orbit.” These were “literally diaphanous shattering screens,” that could scatter enough sunlight in order to reduce global warming — one calculation Teller made concludes that 46 million square miles, or about 1 percent of the surface area of the Earth, of these screens would be necessary.

The climate scientist and Livermore alumnus Ken Caldeira has attributed his own initial interest in solar geoengineering to Lowell Wood, a Livermore researcher and Teller protégé. While often seen as a centrist or even a right wing idea in order to avoid the more restrictionist policies on carbon emissions, solar geoengineering has sparked some interest on the left, including in socialist science fiction author Kim Stanley Robinson’s The Ministry for the Future, which envisions India unilaterally pumping sulfates into the atmosphere in response to a devastating heat wave.

The White House even quietly released a congressionally-mandated report on solar geoengineering earlier this spring, outlining avenues for further research.

While the more than 30 years since the creation of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and the beginnings of Kyoto Protocol have emphasized international cooperation on both science and policymaking through agreed upon goals in emissions reductions, the technological temptation is always present.

And here we can perhaps see that the split between the moralized scientists and their pleas for addressing the problems of the arms race through scientific openness and international cooperation and those of the hawkish technicians, who wanted to press the United States’ technical advantage in order to win the nuclear standoff and ultimately the Cold War through deterrence.

With the IPCC and the United Nations Climate Conference, through which emerged the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement, we see a version of what the postwar scientists wanted applied to the problem of climate change. Nations come together and agree on targets for controlling something that may benefit any one of them but risks global calamity. The process is informed by scientists working with substantial resources across national borders who play a major role in formulating and verifying the policy mechanisms used to achieve these goals.

But for almost as long as climate change has been an issue of international concern, the Tellerian path has been tempting. While Teller’s dreams of massive sun-scattering sheets, nuclear earth engineering, and automated underground reactors are unlikely to be realized soon, if at all, you can be sure there are scientists and engineers looking straight into the light. And they may one day drag us into it, whether we want to or not.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of a climate modeler. It’s been corrected. We regret the error.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

1. Marion County, Indiana — State legislators made a U-turn this week in Indiana.

2. Baldwin County, Alabama — Alabamians are fighting a solar project they say was dropped into their laps without adequate warning.

3. Orleans Parish, Louisiana — The Crescent City has closed its doors to data centers, at least until next year.

A conversation with Emily Pritzkow of Wisconsin Building Trades

This week’s conversation is with Emily Pritzkow, executive director for the Wisconsin Building Trades, which represents over 40,000 workers at 15 unions, including the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, the International Union of Operating Engineers, and the Wisconsin Pipe Trades Association. I wanted to speak with her about the kinds of jobs needed to build and maintain data centers and whether they have a big impact on how communities view a project. Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

So first of all, how do data centers actually drive employment for your members?

From an infrastructure perspective, these are massive hyperscale projects. They require extensive electrical infrastructure and really sophisticated cooling systems, work that will sustain our building trades workforce for years – and beyond, because as you probably see, these facilities often expand. Within the building trades, we see the most work on these projects. Our electricians and almost every other skilled trade you can think of, they’re on site not only building facilities but maintaining them after the fact.

We also view it through the lens of requiring our skilled trades to be there for ongoing maintenance, system upgrades, and emergency repairs.

What’s the access level for these jobs?

If you have a union signatory employer and you work for them, you will need to complete an apprenticeship to get the skills you need, or it can be through the union directly. It’s folks from all ranges of life, whether they’re just graduating from high school or, well, I was recently talking to an office manager who had a 50-year-old apprentice.

These apprenticeship programs are done at our training centers. They’re funded through contributions from our journey workers and from our signatory contractors. We have programs without taxpayer dollars and use our existing workforce to bring on the next generation.

Where’s the interest in these jobs at the moment? I’m trying to understand the extent to which potential employment benefits are welcomed by communities with data center development.

This is a hot topic right now. And it’s a complicated topic and an issue that’s evolving – technology is evolving. But what we do find is engagement from the trades is a huge benefit to these projects when they come to a community because we are the community. We have operated in Wisconsin for 130 years. Our partnership with our building trades unions is often viewed by local stakeholders as the first step of building trust, frankly; they know that when we’re on a project, it’s their neighbors getting good jobs and their kids being able to perhaps train in their own backyard. And local officials know our track record. We’re accountable to stakeholders.

We are a valuable player when we are engaged and involved in these sting decisions.

When do you get engaged and to what extent?

Everyone operates differently but we often get engaged pretty early on because, obviously, our workforce is necessary to build the project. They need the manpower, they need to talk to us early on about what pipeline we have for the work. We need to talk about build-out expectations and timelines and apprenticeship recruitment, so we’re involved early on. We’ve had notable partnerships, like Microsoft in southeast Wisconsin. They’re now the single largest taxpayer in Racine County. That project is now looking to expand.

When we are involved early on, it really shows what can happen. And there are incredible stories coming out of that job site every day about what that work has meant for our union members.

To what extent are some of these communities taking in the labor piece when it comes to data centers?

I think that’s a challenging question to answer because it varies on the individual person, on what their priority is as a member of a community. What they know, what they prioritize.

Across the board, again, we’re a known entity. We are not an external player; we live in these communities and often have training centers in them. They know the value that comes from our workers and the careers we provide.

I don’t think I’ve seen anyone who says that is a bad thing. But I do think there are other factors people are weighing when they’re considering these projects and they’re incredibly personal.

How do you reckon with the personal nature of this issue, given the employment of your members is also at stake? How do you grapple with that?

Well, look, we respect, over anything else, local decision-making. That’s how this should work.

We’re not here to push through something that is not embraced by communities. We are there to answer questions and good actors and provide information about our workforce, what it can mean. But these are decisions individual communities need to make together.

What sorts of communities are welcoming these projects, from your perspective?

That’s another challenging question because I think we only have a few to go off of here.

I would say more information earlier on the better. That’s true in any case, but especially with this. For us, when we go about our day-to-day activities, that is how our most successful projects work. Good communication. Time to think things through. It is very early days, so we have some great success stories we can point to but definitely more to come.

The number of data centers opposed in Republican-voting areas has risen 330% over the past six months.

It’s probably an exaggeration to say that there are more alligators than people in Colleton County, South Carolina, but it’s close. A rural swath of the Lowcountry that went for Trump by almost 20%, the “alligator alley” is nearly 10% coastal marshes and wetlands, and is home to one of the largest undeveloped watersheds in the nation. Only 38,600 people — about the population of New York’s Kew Gardens neighborhood — call the county home.

Colleton County could soon have a new landmark, though: South Carolina’s first gigawatt data center project, proposed by Eagle Rock Partners.

That’s if it overcomes mounting local opposition, however. Although the White House has drummed up data centers as the key to beating China in the race for AI dominance, Heatmap Pro data indicate that a backlash is growing from deep within President Donald Trump’s strongholds in rural America.

According to Heatmap Pro data, there are 129 embattled data centers located in Republican-voting areas. The vast majority of these counties are rural; just six occurred in counties with more than 1,000 people per square mile. That’s compared with 93 projects opposed in Democratic areas, which are much more evenly distributed across rural and more urban areas.

Most of this opposition is fairly recent. Six months ago, only 28 data centers proposed in low-density, Trump-friendly countries faced community opposition. In the past six months, that number has jumped by 95 projects. Heatmap’s data “shows there is a split, especially if you look at where data centers have been opposed over the past six months or so,” says Charlie Clynes, a data analyst with Heatmap Pro. “Most of the data centers facing new fights are in Republican places that are relatively sparsely populated, and so you’re seeing more conflict there than in Democratic areas, especially in Democratic areas that are sparsely populated.”

All in all, the number of data centers that have faced opposition in Republican areas has risen 330% over the past six months.

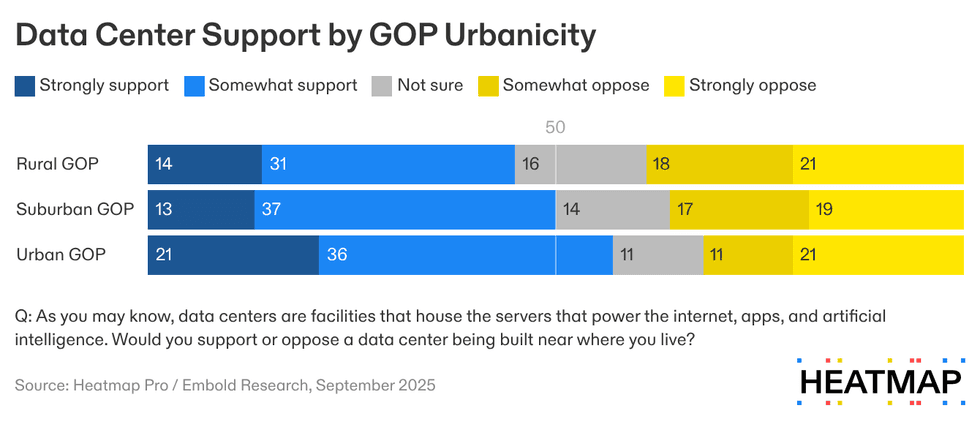

Our polling reflects the breakdown in the GOP: Rural Republicans exhibit greater resistance to hypothetical data center projects in their communities than urban Republicans: only 45% of GOP voters in rural areas support data centers being built nearby, compared with nearly 60% of urban Republicans.

Such a pattern recently played out in Livingston County, Michigan, a farming area that went 61% for President Donald Trump, and “is known for being friendly to businesses.” Like Colleton County, the Michigan county has low population density; last fall, hundreds of the residents of Howell Township attended public meetings to oppose Meta’s proposed 1,000-acre, $1 billion AI training data center in their community. Ultimately, the uprising was successful, and the developer withdrew the Livingston County project.

Across the five case studies I looked at today for The Fight — in addition to Colleton and Livingston Counties, Carson County, Texas; Tucker County, West Virginia; and Columbia County, Georgia, are three other red, rural examples of communities that opposed data centers, albeit without success — opposition tended to be rooted in concerns about water consumption, noise pollution, and environmental degradation. Returning to South Carolina for a moment: One of the two Colleton residents suing the county for its data center-friendly zoning ordinance wrote in a press release that he is doing so because “we cannot allow” a data center “to threaten our star-filled night skies, natural quiet, and enjoyment of landscapes with light, water, and noise pollution.” (In general, our polling has found that people who strongly oppose clean energy are also most likely to oppose data centers.)

Rural Republicans’ recent turn on data centers is significant. Of 222 data centers that have faced or are currently facing opposition, the majority — 55% —are located in red low-population-density areas. Developers take note: Contrary to their sleepy outside appearances, counties like South Carolina’s alligator alley clearly have teeth.