You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Here’s where Biden’s climate law is having the biggest impact on the automotive industry — and where it’s falling short.

Around this time last summer, it seemed more apparent than ever that 2023 would be the year the gasoline-free automotive future was set to begin. After a decade that included electric vehicle fits and starts, Volkswagen’s diesel cheating scandal, the rise of Tesla, the EV boom in China, and a whole new generation of car buyers more aware of their personal impact on the climate than ever, it felt like the dawn of an EV-focused tomorrow was just around the corner. All it needed was a spark.

The Inflation Reduction Act, an admittedly poorly named piece of legislation packed with climate and green energy provisions, was meant to be exactly that. On the automotive front, the Biden administration’s signature legislation package included massive subsidies for EV battery plants, strict rules around where cars are produced and batteries are sourced, and a reset on America’s outdated EV tax incentive scheme for car buyers. It seemed grand on a scale not seen since the Johnson years: thousands of jobs, some $100 billion in funding, and a chance for America to kneecap China in the EV arms race.

So a year after the IRA’s passage, is all this investment working? The definitive answer is this: mostly, kinda.

While it’s highly questionable that the IRA has successfully Reduced Inflation, the effect of the legislation on America’s automotive manufacturing landscape has already been palpable. A recent report from the Environmental Defense Fund shows EV industry investments in the U.S. rising in 2021 around the passage of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, before taking off in a near-vertical fashion after the IRA was passed.

I decided to grade the IRA’s impact on America’s automotive sector — not just the Big Three U.S. automakers, but all companies who make cars here and support them — in a few key areas.

What I found is that a year in, the IRA feels like it could permanently reset our car industry. But in some key areas, its effects aren’t even close to being seen, and on other fronts, the IRA has caused a number of unintended consequences that will play out for years to come.

Get one great climate story in your inbox every day:

This is arguably the biggest shift we’ve seen thanks to the IRA, and it’s certainly working.

Making batteries for tomorrow’s EVs won’t be as simple as turning car engine plants into battery plants; the supply chain, manufacturing process, and labor needs are entirely different. And so new facilities are springing up left and right to meet this moment.

The Electrification Coalition, a nonprofit policy organization that advocates for EV adoption, identified more than a dozen battery manufacturing and recycling factories that have been announced or are under construction thanks to IRA incentives. These projects are, on average, $3 billion or more, and they’ll provide batteries for future cars from General Motors, Rivian, Hyundai, Tesla, Volkswagen’s new electric Scout brand, and more.

Would this new battery ecosystem have happened without the IRA? Maybe. But certainly not this quickly or at this scale. The automakers may be moving in the direction of electrification, but it’s doing so begrudgingly and these incentives — coupled with state and local ones as well — gave them a reason to move quicker than “the market” would’ve done.

That’s good news for batteries. What about the cars themselves? Since the IRA heavily incentivizes batteries and EVs to be made locally — which I’ll touch on in a moment — it’s kicking off a surge in U.S. car manufacturing the likes of which haven’t been seen in decades.

While battery factories themselves are getting the lion’s share of the attention and money, automakers are adding new factories, expanding existing ones, and retooling lines to scale up their EV outputs.

Granted, many automakers are still investing heavily into (or hedging their bets on) their profitable gasoline models, especially big trucks and SUVs. But EV production is ramping up in America and that scale should eventually drive prices down. Simply put, if a car company — GM, Ford, Nissan, BMW, Hyundai, all of them — builds in the U.S., they’re about to start making EVs here too.

There’s an undercurrent that can be found across all of the Biden administration’s climate and tech investments: cutting off a rising China in countless areas. It’s why only EVs with “final assembly” in North America, that don’t source batteries or components from China, qualify for tax incentives. China has made huge investments into not only its own EV industry but controlling the supply chain around it, and America doesn’t want to cede that to a potentially hostile, non-allied peer state that has a horrific record on human rights and civic freedoms.

Is it working? So far, yes. However, it’s not going to happen overnight. Just as the Center for Strategic and International Studies called it last year, “in the short term it will be difficult to avoid Chinese supply chains.” That’s true of chips, minerals, and everything else.

Moreover, don’t expect automakers to give up the potential of exporting Chinese-made cars. Tesla already sells China-made EVs in Canada, and Volvo has found a George Washington-era loophole to sell the affordable EX30 electric crossover in America without steep tariff penalties. IRA rules may keep Chinese batteries out of our country and stiff tariffs hamper automakers like BYD for now, but this side of things is far from settled.

Now, it’s time for our lesson in unintended consequences. The new $7,500 EV tax credits have strict requirements; essentially, the cars and their batteries have to be built in North America. Given the long-term nature of these investments, not every automaker with an EV lineup can meet those rules for now, leaving a lot of cars out of the credit. (South Korea’s Hyundai Motor Group, in particular, got pretty burned here, leaving its excellent EVs on the expensive side.)

Long-term, these cars and their batteries will be built locally and more cars will qualify for the tax credit. For now, the high cost of EVs is proving to be a major deterrent to adoption. Buyers, squeezed by interest rates and the rising cost of everything, are having trouble justifying the switch. So far the biggest winner is Tesla, which has always been building EVs and batteries in America.

I think a better approach would’ve been to allow all EVs to qualify for the full tax credit until, say, 2026 or so; after that, and perhaps after a gradual phase-in, automakers would have to build local or charge higher prices. That would’ve given them time to ramp up these factories and pushed EV adoption harder at the same time. At the start of the year, before a ton of EVs and hybrids got kicked out of the program, that’s exactly the trend we saw.

That’s what I would’ve done. But, to date, Joe Biden has not put me in charge of such things.

This one is due to be an objective win for the IRA. That Environmental Defense Fund report counts 84,800 jobs that have been announced for the EV industry in America since the IRA’s passage.

According to their data, nearly all of those are located in Southern states. Georgia’s the biggest winner here, believe it or not. And Tennessee, South and North Carolina, and Kentucky are all seeing, or will soon see, big booms in EV-related job growth. The same is true for Michigan, the home of America’s auto industry, as well as lithium-rich Nevada, where Tesla has had a foothold for years.

Again, there’s another universe where the IRA didn’t pass and all of those jobs went to China instead as America’s automakers put their patriotism on the back burner to chase lower labor costs and easy profits. The U.S. is getting a major employment boost instead.

But there’s a difference between “jobs” and “good jobs.” Take a newly militant United Auto Workers union, currently locked into unusually bitter contract negotiations with the Big Three American automakers. One thing they’re mad about: those battery factories going up everywhere, especially the joint-venture ones, don’t automatically lead to union jobs. (One GM-LG battery plant in Ohio voted to unionize with the UAW last year but doesn’t have a contract yet.)

The result is that those battery plant workers could make considerably less money than America’s unionized auto workers, as my colleague Emily Pontecorvo reported in June. Adding insult to injury, EVs generally need fewer parts and labor than conventional cars to assemble; indeed, those battery plant jobs could one day form the bulk of America’s automotive labor force.

The UAW did support the IRA’s passage last year. But that also happened before the union’s much tougher current leadership came in; I’m not convinced it would have gone the same way today. In general, the law doesn’t do a ton for labor, and that’s why the reliably Democratic UAW has held off on endorsing Biden.

So far, the Biden administration doesn’t have a great answer for this, either. The president himself is doing the “Can’t we all just get along?” dance, but that may be the best he can do as he navigates climate, geopolitical, industry, and labor needs at the same time. And the move to EVs is expected to define the automotive labor world — here and globally — for the next few decades.

As Ryan Cooper astutely noted this week, the IRA’s biggest problem is arguably one of awareness. Very few people seem to know about these investments or what’s coming from them. That lack of awareness could be the IRA’s biggest threat.

Maybe that’s a problem more for Biden than the EV industry, America’s supply chain, or the climate, but when nobody knows about the president’s biggest achievement — especially in all those red states where the jobs are going — you have to wonder what a change at the White House next year could mean for all of this momentum. It’s not like those battery plants under construction will just disappear, but I wouldn’t put it past a less climate-focused White House (or Congress) to find a way to thwart all this progress.

There’s also the rising right-wing backlash to EVs in general, predicated more on the messaging power of the fossil fuel industry and our own endlessly stupid culture wars. In short, though these investments do take time, very few people seem to know about them or see the benefits that will come from them.

Auto industries are always heavily subsidized and regulated by the countries they come from. It was true of Japan after World War II, it’s been true of China for the past 20 years, and it’s certainly been true in various ways in America for a century. The IRA is just the biggest such move the U.S. has seen to modernize, compete and innovate in a world where gas cars could eventually be discarded as obsolete technology.

The groundwork has been laid. Now we’ll find out if it has staying power.

Read more about the politics of electric vehicles:

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Two international law experts on whether the president can really just yank the U.S. from the United Nations’ overarching climate treaty.

When the Trump administration moved on Wednesday to withdraw the U.S. from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, we were left to wonder — not for the first time — can he really do that?

The UNFCCC is the umbrella organization governing UN-organized climate diplomacy, including the annual climate summit known as the Conference of the Parties and the 2015 Paris Agreement. The U.S. has been in and out and back into the Paris Agreement over the years, and was most recently taken out again by a January 2025 executive order from President Trump. The U.S. has never before attempted to exit the UNFCCC — which, unlike the Paris Agreement, it joined with the advice and consent of the Senate.

Whether or not a president can unilaterally remove the U.S. from a Senate-approved treaty is somewhat uncharted legal territory. As University of Pennsylvania constitutional law professor Jean Galbraith told me, “This is an issue on which the text of the constitution is silent — it tells you how to make a treaty, but it doesn’t tell you anything about how to unmake a treaty.” Even if a president can simply withdraw from a treaty, there’s still the question of what happens next. Could a future president simply rejoin the UFCCC? Or would they again need to seek the advice and consent of the Senate, which would require getting 67 senators to agree that international climate diplomacy is a worthy enterprise? And what does all of this mean for the future of the Paris Agreement? Is the U.S. locked out for good?

In an attempt to wrap my head around these questions, I spoke to both Galbraith and Sue Biniaz, a lecturer at Yale School of the Environment and a former lead climate lawyer at the State Department who worked on both the Paris Agreement and the UNFCCC. Biniaz and Galbraith were part of a 2018 symposium on the question of treaty withdrawal that was prompted, in part, by Trump’s first attempt to remove the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, during his first term in the White House. Those conversations led Galbraith to consider the question of rejoining treaties in a 2020 Virginia Law Review article. Suffice it for now to say that both questions are complicated, but we dig into the answers to both and more in our conversation below.

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

At the most basic level, what are the constitutional questions at play in an executive withdrawal from the UNFCCC?

Galbraith: Typically, the U.S. president needs to think about both international law and domestic law. And as a matter of international law, there is a withdrawal provision in the UNFCCC that says you can withdraw after you’ve been in it for a few years, after one year of notice. Assuming they give their notice of withdrawal and wait a year, this is an issue on which the text of the constitution is silent — it tells you how to make a treaty, but it doesn’t tell you anything about how to unmake a treaty.

And we have no definitive answer from the courts. The closest they got to deciding that was in a case called Goldwater v. Carter, which was when President Carter terminated the mutual defense treaty with Taiwan. That was litigated, and the Supreme Court ducked — four justices said this is a political question that we’re not going to resolve, and one justice said this case is not ripe for resolution because I don’t know whether or not Congress likes the withdrawal. There was no majority opinion, and there was no ruling on the merit for the constitutional question.

Presidents have exercised the authority to withdraw the United States from various international agreements. So in practice, it happens. The constitutionality has not been finally settled.

Both Trump administrations have removed the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, but the Paris Agreement was not a Senate-ratified treaty, whereas the UNFCCC is. How does that change things?

Galbraith: The text of the constitution only clearly spells out one way to make an international treaty, in the treaty clause [of Article II]. When you make an Article II treaty, it’s signed by the president and secretary of state. It goes over to the Senate; the Senate provides advice and consent — the U.S. is still not in it. At that point, the president has to take a final act of ratifying the treaty, which means depositing the instrument of ratification with the international depository, and that’s the moment you’re in. And it’s perfectly permissible for a president after the Senate has given advice and consent not to ratify a treaty, or to leave those resolutions of advice and consent for years and then go ahead and ratify.

In practice, you have all these kinds of other ways of making [a treaty]. You have what happened with the Paris Agreement, where the president does it largely on their own authority, but maybe pointing to pre-existing facts of, say, the UNFCCC’s existence. You have some international agreements that have been negotiated, then taken to Congress rather than to the Senate. Sometimes you have Congress pass a law that says, Please make this kind of agreement. So you have a lot of different pathways to making them. And I think there is a story in which the pathway to making them should be significant in thinking about, what is the legitimate, constitutional way for exiting them?

To me, it’s pretty obvious that if you don’t get specific approval for an agreement in the first place, then you should be able to unilaterally withdraw, assuming you’re doing so consistent with international law. I think the concerns around the constitutionality of withdrawal are more significant for the UNFCCC than they are for the Paris Agreements. But there nonetheless is this fairly strong body of practice in which presidents have viewed themselves as authorized to withdraw without needing to go to Congress or the Senate.

Biniaz: The Senate doesn’t ratify. It sounds like a detail, but the Senate basically authorizes the president to ratify — they give their advice and consent. And that’s important because it’s not the Senate that decides whether we join an agreement. They authorize the president, the president does not have to join. And that becomes relevant when we talk about withdrawing and rejoining.

We did not address, when we sent up the framework convention, whether it was legally necessary to send it to the Senate. But we sent it in any event, and it was approved basically unanimously by the full Senate back in 1992. With respect to the Paris Agreement, there are a lot of different considerations when you’re trying to figure out whether something needs to go to the Senate or not, but the fact that we already had a Senate-approved convention changed the legal calculus as to whether this Paris Agreement needed to go to the Senate. And then when the Paris Agreement ended up essentially elaborating the convention and the targets were not legally binding, we decided we could do it as an executive agreement. There was some quibbling in some quarters — more from a political point of view than a legal point of view — but I didn’t hear any objection from a legal point of view.

Now, in terms of withdrawing from an agreement, whether or not an agreement has been approved by the Senate, my view would be: The president can withdraw unilaterally. That is the mainstream view. It’s certainly the view that the president can withdraw unilaterally from an agreement that didn’t even go to Congress, like the Paris Agreement. And in part, that’s for the reasons that I mentioned. The Senate is not deciding to join the agreement — they’re authorizing, but it’s up to the president whether to actually join, and the president does that unilaterally. And then the mirror image of that would be he or she can withdraw unilaterally.

There’s a related legal question that has not been litigated, which is if Congress passes a law that says, Thou shalt not withdraw from a particular agreement, would that law be constitutional? Some would say no, because the president can withdraw, and so the Congress can’t fetter that right. So that’s like uncharted waters, but that’s not a live issue in this case.

Trump took the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement. Biden put the us back into the Paris Agreement. Trump then took us out of the Paris Agreement again, and is now withdrawing the U.S. from the umbrella organization of the Paris Agreement. I assume that would complicate the efforts of a future president to rejoin the Paris Agreement. Would it be possible for them to rejoin the framework convention? What would have to happen?

Galbraith: So first, the framework convention is the gateway to the Paris Agreement. There’s a provision in the Paris Agreement that says, in order to be in the Paris Agreement, you’ve got to be in the framework convention. And so as a matter of international law, in order to rejoin the Paris Agreement — at least unless it were dramatically amended, which is its own unlikely thing — you would need to be a member of the UNFCCC, which does mean that the question of how you rejoin the UNFCCC becomes significant. We have very little practice on any kind of rejoining. I myself think that the president could simply rejoin the UNFCCC by pointing back to the original Senate resolution of advice and consent to it. You could go back to the Senate. You could ask Congress for a resolution.

My own view is that if the president withdraws the U.S., well, they still have on the books this resolution in which the Senate has consented to ratification — they want to go back in, they go back in. I think this is pretty logically clear, but also an important constraint on presidential power. Because it’s a much more concerning increase in presidential power if you have to do all the work of getting two-thirds of the Senate, then any president can, just at the snap of their fingers, take you out, and you have to go all the way back to the beginning.

Biniaz: There are many options. One is a straightforward option: You go back to the Senate, get 67 votes. Another would be you get both houses of Congress to authorize it [on a majority vote basis]. Another would be — and there may be more — but another would be the idea that the original Senate resolution which we used in 1992 to join still exists, and nothing has extinguished it. And there the analogy would be to a regular law.

There’s several laws in the United States that authorized the president to join some kind of international body or institution. There’s a law that authorizes the president to join the International Labor Organization. There’s a law that authorized the president to join UNESCO. In both of those cases, the U.S. has been in and out and back in — and I think in one case, at least, back out. No one has batted an eye because, well, it’s a law. So the question there would be, is there any reason why a Senate resolution would be any different? Professor Galbraith explores in her law review article that exact question, and concludes that, no, there shouldn’t be a difference — I’m simplifying, but that’s the gist. And under that theory, yeah, a future president could rejoin the convention on his or her own, utilizing that authority, and then after having rejoined the convention, rejoin the Paris Agreement.

So you mentioned that there’s a provision in the UNFCCC that says you have to give notice that you’re exiting, and you wait a year, and then you exit. What does not waiting a year look like?

Galbraith: It can happen that an entity will announce its exit and then violate international law by violating the treaty terms during that one-year period. If there are, say, reporting obligations that the United States has, it would be a violation of international law not to meet those during the period while you’re still a party to the treaty.

This is obviously an escalation of Trump’s previous actions to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, in the sense that it cuts off the path to rejoining that. What does this tell us about the way the Trump administration views its position within global climate diplomacy, and also the international community, period?

Galbraith: It adds to the impression that we already see other contexts, which is that the second Trump administration is even less inhibited and climate-aware than the first administration was — which is really saying something, right? This is an escalation of a position that was already an international outlier. Every other country is in these things, and it shows a real, powerful, and deeply upsetting failure to address the crisis of the global commons.

Biniaz: The way I think about it is that, during Trump 1, it was more like there was an absence of a positive — so in other words, the administration continued to participate in negotiations. They were not pressing countries to take climate action, but neither were they pressing countries not to take climate action. This administration, you could think of it as not just the absence of a positive, but the presence of a negative. I don’t mean that in any judgmental sense. I just mean there’s been much more of an active push from the administration for others to sort of follow suit or to vote against climate-related agreements such as at the [International Maritime Organization]. That’s quite a difference between 1 and 2.

Going into this past year’s COP, it seemed like there was already a sense that international climate diplomacy was, if not dead, at least the wind had come out of the sails. Do you agree? And if so, do you think that wind will come back?

Biniaz: You have to think of international climate diplomacy very broadly. It’s not just the UNFCCC Paris Agreement and decisions that are taken by consensus. That was pretty thin gruel that came out of COP30. But if you think of international climate diplomacy more broadly as all kinds of initiatives, coalitions that are operating among subgroups of countries and at all levels of stakeholders, there’s really a lot going on in what people call the real world. I think over the next couple of years, the proportion of action that’s taken officially, by consensus, dips somewhat, and action goes up. And maybe that balance shifts over time. But I think it’s wrong to judge climate diplomacy simply by what was achievable by 197 countries, because that’s always going to be the hardest to achieve, with or without the United States.

I think it’s more difficult without a pro-climate U.S. because of the role the U.S. has historically played, in terms of promoting ambition and brokering compromises and that kind of thing. But I don’t think, if you only look at that, it’s not the right metric for judging all of global climate diplomacy.

On Venezuela’s oil, permitting reform, and New York’s nuclear plans

Current conditions: Cold temperatures continue in Europe, with thousands of flights canceled at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, while Scotland braces for a winter storm • Northern New Mexico is anticipating up to a foot of snow • Australia continues to swelter in heat wave, with “catastrophic fire risk” in the state of Victoria.

The White House said in a memo released Wednesday that it would withdraw from more than 60 intergovernmental organizations, including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the international climate community’s governing organization for more than 30 years. After a review by the State Department, the president had determined that “it is contrary to the interests of the United States to remain a member of, participate in, or otherwise provide support” to the organizations listed. The withdrawal “marks a significant escalation of President Trump’s war on environmental diplomacy beyond what he waged in his first term,” Heatmap’s Robinson Meyer wrote Wednesday evening. Though Trump has pulled the United States out of the Paris Agreement (twice), he had so far refused to touch the long-tenured UNFCCC, a Senate-ratified pact from the early 1990s of which the U.S. was a founding member, which “has served as the institutional skeleton for all subsequent international climate diplomacy, including the Paris Agreement,” Meyer wrote.

Among the other organizations named in Trump’s memo was the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which produces periodic assessments on the state of climate science. The IPCC produced the influential 2018 report laying the intellectual foundations for the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

More details are emerging on the Trump administration’s plan to control Venezuela’s oil assets. Trump posted Tuesday evening on Truth Social that the U.S. government would take over almost $3 billion worth of Venezuelan oil. On Wednesday, Secretary of Energy Chris Wright told a Goldman Sachs energy conference that “going forward we will sell the production that comes out of Venezuela into the marketplace.” A Department of Energy fact sheet laid out more information, including that “all proceeds from the sale of Venezuelan crude oil and oil products will first settle in U.S. controlled accounts,” and that “these funds will be disbursed for the benefit of the American people and the Venezuelan people at the discretion of the U.S. government.” The DOE also said the government would selectively lift some sanctions to enable the oil sales and transport and would authorize importation of oil field equipment.

As I wrote for Heatmap on Monday, sanctions are just one barrier to oil development among a handful that would have to be cleared for U.S. oil companies to begin exploiting Venezuela’s vast oil resources.

In a Senate floor speech, Senator Martin Heinrich of New Mexico blasted the Trump administration’s anti-renewables executive actions, saying that the U.S. is “facing an energy crisis of the Trump administration’s own making,” and that “the Trump administration is dismantling the permitting process that we use to build new energy projects and get cheaper electrons on the grid.” Heinrich, a Democrat, is the ranking member of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources and a key player in any possible permitting reform bill. Though he said he supports permitting reform in principle, calling for “a system that can reliably get to a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’ on a permit in two to three years — not 10, not 17,” he said that “any permitting deal is going to have to guarantee that no administration of either party can weaponize the permitting process for cheap political points.” Heinrich called on Trump officials “to follow the law. They need to reverse their illegal stop work orders, and they need to start approving legally compliant energy projects.”

He did offer an olive branch to the Republican senators with whom he would have to negotiate on any permitting legislation, noting that “the challenge to doing permitting reform is not in this building,” specifying that Senators Mike Lee, chair of the ENR Committee, and Shelly Moore-Capito, chair of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, have not been barriers to a deal. Instead, he said, “it is this Administration that is poisoning the well.”

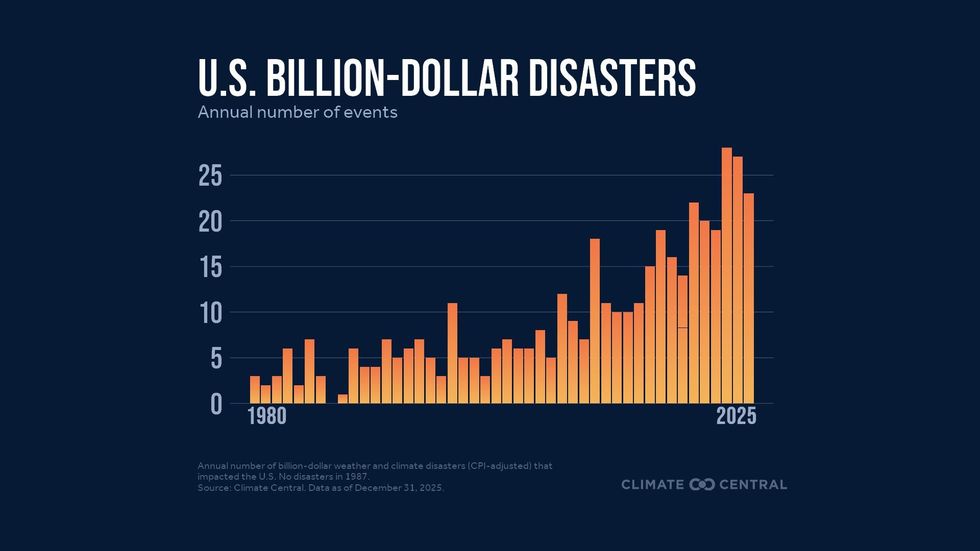

The climate science nonprofit Climate Central released an analysis Thursday morning ranking 2025 “as the third-highest year (after 2023 and 2024) for billion-dollar weather and climate disasters — with 23 such events causing 276 deaths and costing a total of $115 billion in damages,” according to a press release.

Going back to 1980, the average number of disasters costing $1 billion or more to clean up was nine, with an average total bill of $67.9 billion. The U.S. hit that average within the first weeks of last year with the Los Angeles wildfires, which alone were responsible for over $61 billion in damages, the most economically damaging wildfire on record.

The New York Power Authority announced Wednesday that 23 “potential developers or partners,” including heavyweights like NextEra and GE Hitachi and startups like The Nuclear Company and Terra Power, had responded to its requests for information on developing advanced nuclear projects in New York State. Eight upstate communities also responded as potential host sites for the projects.

New York Governor Kathy Hochul said last summer that New York’s state power agency would go to work on developing 1 gigawatt of nuclear capacity upstate. Late last year, Hochul signed an agreement with Ontario Premier Doug Ford to collaborate on nuclear technology. Ontario has been working on a small modular reactor at its existing Darlington nuclear site, across Lake Ontario from New York.

“Sunrise Wind has spent and committed billions of dollars in reliance upon, and has met the requests of, a thorough review process,” Orsted, the developer of the Sunrise Wind project off the coast of New York, said in a statement announcing that it was filing for a preliminary injunction against the suspension of its lease late last year.

The move would mark a significant escalation in Trump’s hostility toward climate diplomacy.

The United States is departing the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the overarching treaty that has organized global climate diplomacy for more than 30 years, according to the Associated Press.

The withdrawal, if confirmed, marks a significant escalation of President Trump’s war on environmental diplomacy beyond what he waged in his first term.

Trump has twice removed the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, a largely nonbinding pact that commits the world’s countries to report their carbon emissions reduction goals on a multi-year basis. He most recently did so in 2025, after President Biden rejoined the treaty.

But Trump has never previously touched the UNFCCC. That older pact was ratified by the Senate, and it has served as the institutional skeleton for all subsequent international climate diplomacy, including the Paris Agreement.

The United States was a founding member of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. It first joined the treaty in 1992, when President George H.W. Bush signed the pact and lawmakers unanimously ratified it.

Every other country in the world belongs to the UNFCCC. By withdrawing from the treaty, the U.S. would likely be locked out of the Conference of the Parties, the annual UN summit on climate change. It could also lose any influence over UN spending to drive climate adaptation in developing countries.

It remains unclear whether another president could rejoin the framework convention without a Senate vote.

As of 6 p.m. Eastern on Wednesday, the AP report cited a U.S. official who spoke on condition of anonymity because the news had not yet been announced.

The Trump administration has yet to confirm the departure. On Wednesday afternoon, the White House posted a notice to its website saying that the U.S. would leave dozens of UN groups, including those that “promote radical climate policies,” without providing specifics. The announcement was taken down from the White House website after a few minutes.

The White House later confirmed the departure from 31 UN entities in a post on the social network X, but did not list the groups in question.