You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

The former Department of Energy chief commercialization officer talks about the public sector’s role in catalyzing new clean energy.

Vanessa Chan didn’t think she had the right temperament to work in government. After a 13-year stint as a partner at McKinsey, six years as a partner at the angel investment firm Robin Hood Ventures, and four years at the University of Pennsylvania, most recently as professor of practice in innovation and entrepreneurship, Chan considered herself to be an impatient, get-it-done type — anathema to the traditionally slow, procedurally complex work of governing.

But the Energy Act of 2020 had just formalized a new role within the Department of Energy ideally suited to her skills: Chief Commercialization Officer, which would also serve as the director of the Office of Technology Transitions. Who would fill these dual roles was to be the decision of then-incoming Secretary of Energy Jennifer Granholm, who found a kindred spirit in Chan. Under her leadership, Chan told me, “I found someone who’s less patient than me.”

In her four years at the DOE, the OTT’s annual budget — which she referred to as “literally a rounding error to most people” — grew from $12.6 million to $56.6 million. She leveraged it to its fullest extent, establishing a precedent for the potential of this small but mighty office. Chan spearheaded the “Pathways to Commercial Liftoff” reports that provide investors with a path to market for the most important decarbonization technologies, and announced over $41 million in funding for 50 clean energy projects across all of the nations 17 national labs through the Technology Commercialization Fund.

She also changed the way the DOE, national labs, venture capitalists, and startups alike talk about getting ready for primetime with the Adoption Readiness Level framework, which put a much-needed focus on factors such as economic viability, regulatory hurdles, and supply chain constraints in the same way that the established Technology Readiness Levels, pioneered by NASA, focus on the question of whether a technology actually works.

Now Chan is back at the University of Pennsylvania in a new, extremely apt role: the Inaugural Vice-Dean of Innovation and Entrepreneurship. She’s weaving lessons learned from her time in the public and private sectors into academia, where her goal is to help incorporate real-world skills into the education of engineers and PhD scholars to prime them for maximum impact upon graduation.

“It’s such a disservice if you invent something and it never sees the light of day,” she told me. “So we need to make sure that isn’t happening and we increase our odds of things making it to the market.”

Over two separate interviews, one before President Trump’s inauguration and one after, I asked Chan how her work with the DOE has helped climate technologies move from the lab to the market, the challenges that remain, and what to keep an eye on in the new administration. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

How did you get recruited for this job? Was government work even on your radar before?

No, this was never on my vision board. But the way in which this came about was in 2016, there was a workshop that was being led by DOE on a potential new foundation that was going to be focused on commercialization. And one of my former clients told the person running the workshop, if you’re talking about technology commercialization, you have to talk to Vanessa Chan. And when I was there, I just yapped off about all the issues that I see with commercialization and what the federal government should be doing about it. And I didn’t think anything of it.

And then fast forward to 2020, I get this cryptic email saying, “Hey, the Biden-Harris administration is interested in you.” I spent all the time during the interview [with the Biden-Harris team] going, “Here’s my thing about commercialization, but I don’t think you guys want me, because I’m someone who works really fast. I have no patience for bureaucracy. I like to disrupt. I don’t like the status quo.” And they’re like, that’s exactly what we want.

How did the DOE, and the OTT in particular, really undergo a shift in the Biden administration?

Historically, DOE has been very focused on research and development. And then when the [Bipartisan Infrastructure Law] and [Inflation Reduction Act] got passed, now there was half-a-trillion dollars going towards demonstration and deployment, and it became a lot more fun being the chief commercialization officer.

The mantra that we’ve had is that the clean energy transition — and quite frankly, commercialization — has to be private sector-led but government-enabled. Because in the end, it’s the private sector that’s actually commercializing. It’s not the government. DOD can buy stuff to bring things to market, but DOE, we’re an enabler. And unless the private sector has sustainable, viable economic models, nothing will ever be commercialized.

How does your work intersect with other DOE agencies that are focused on commercialization, like the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations and the Loan Programs Office?

I worked very closely with all of them. In particular, one of the things that was really important to do was to get us on the same page of what it actually means to deploy technologies. So I quarterbacked an effort called the Pathways to Commercial Liftoff, which OCED, LPO, and any program office that was touching research, development, demonstration, and deployment was a part of.

If we use hydrogen hubs as an example, OCED was given $8 billion towards hydrogen. When we did the hydrogen liftoff report, what we found was a few things. One is that electrolyzer costs are super high, and so we have to be able to drive those downward to make the unit economics work. We have an issue where there is no midstream infrastructure. We also had a chicken-and-the egg, which is pretty classic: No one wants to buy hydrogen until the supply chain is stood up, [but] the supply chain doesn’t want to stand up until they know they actually have offtake agreements.

What we did with OCED was, we took $7 billion to invest in seven hydrogen hubs across the nation, and then we reserved $1 billion to create an offtake demand mechanism. And that’s the first time ever that the federal government has actually focused on a demand activation program.

Have these liftoff reports been well received on both sides of the aisle? Do you think they’ll continue to be referenced in the new administration?

We were very, very, very fact-driven. There’s no policy by design, because in the end it’s all about, what does it take for a technology to make sense, for it to be in the market? So it’s not Republican or Democratic, it’s just — what does the private sector have to do? I’m really hoping they’re not seen as partisan and really more a synthesis of what’s required for the private sector to actually scale technology.

What are some additional successes from your time at the DOE?

An example program is MAKE IT, which is Manufacturing of Advanced Key Energy Infrastructure Technologies, which was a program that we created with OCED in order to figure out ways in which we could try to help bolster manufacturing across the nation. We also have this program called EPIC, the Energy Program for Innovation Clusters, and we have funded over 80 incubators and accelerators across the nation, which are supporting startups.

We’ve created a voucher program for startups and smaller organizations — sometimes there’s very tactical things that they need help on, and they need a small dollar amount, like a couple-hundred-thousand-dollars to tackle that. We’re like, Oh, you need to do techno-economic analysis? We’re going to pair you with this organization here that can do it, and you don’t have to negotiate anything with them. We’re just going to send them the money, you’re given a voucher, and you just call them.

When I talk with venture capitalists, something that often comes up is the difficulty of getting startups through the so-called Valley of Death, the funding gap between a company’s initial rounds and its commercial scale-up. How do you think about the public sector’s role in helping companies through this stage?

First of all, this private sector-led, government-enabled idea around commercialization is really important. And the work we’ve done with Liftoff and how we’ve gotten money out the door has really worked, because for every dollar going out the door from DOE, we’ve seen $6 matching from the private sector. That in itself is showing that there’s a way for the public sector to nudge the private sector to act.

What I’ll tell you, though, is that I think there needs to be a wholesale reframe around how the private sector thinks about investments and the returns that they want on them. Right now, we are in the Squid Games, where everyone is first in line to be sixth or seventh, no one is first in line to be first, second, or third, because they know the person who is first, second, or third is going to lose money. So what we need to do is figure out, how do we have the ecosystem crowdsource the first 10 of a kind, so that we get to the tipping point where the unit economics are working? How do we get the private sector to promise to buy technologies when they’re not quite there? How do we in the public sector help on the back end?

What are other primary barriers to commercialization that you see?

Another big barrier is that the time clock for moving up the learning curve and moving down the cost curve is quite long in some of these hard-tech technologies. And so the challenge is, how do we convince CEOs to make investments in something which is not going to benefit them, but benefit a CEO two or three down the line? Humans just don’t work that way, right? They’re all about earnings per share and quarterly earning reports and so forth.

Now the challenge is, if we don’t do it, then countries like China are going to do it. This is what happened in solar: We invented the technology, but China was willing to take a loss in order to get up the learning curve and drive down the cost curve, and we need to figure out how to do the same.

Have you been in touch with anyone from the Trump administration? Do you know who your successor will be?

No idea. My team didn’t even know who I was until day one. But what I’ll tell you is that OTT has really strong bipartisan support because we’re commercializing technologies, which is creating jobs, and I think everyone understands the importance of this. Also for the [Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation] I was very deliberate with the other ex officio board members to make sure we had a bipartisan board. We have 13 board members that we appointed here at DOE, and I have representation from every single administration since George H.W. Bush, including two Trump appointees.

I really do hope that whoever sits in my seat will reach out, and I left a letter offering that, too. Hopefully they do give me a call because I really want to wish them every success in the work that they’re doing.

What’s it like to be back at the University of Pennsylvania, watching this new administration from a civilian perspective?

This was the best job ever, so I’m just sad in general to not be at the Department of Energy because I really enjoyed the work that we were doing there. A lot of the money from the BIL and IRA were used to catalyze many, many red states. I am hopeful that people in power recognize this and are going to do right by those counties. Because I think, in the end, what we’re trying to do is really help with American jobs and competitiveness.

Any thoughts on the executive order that’s frozen disbursement of funds from BIL and IRA?

I don’t know, because I always think it’s not right to be on the outside in, trying to figure out what different executive orders are trying to say or not say. We all have to wait to see how these get executed upon.

What do you think people should be keeping an eye on to gauge the impacts that these sweeping executive orders are having?

In my mind it’s really, is the private sector spooked? Are they going to continue to invest the money that’s needed for these manufacturing plants to continue and so forth? Because in the end, it’s the private sector that actually is driving American competitiveness — the federal government is a catalyst. And so I think what I’d be looking to is the private sector. Are they stopping the momentum that we helped to kickstart?

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Two international law experts on whether the president can really just yank the U.S. from the United Nations’ overarching climate treaty.

When the Trump administration moved on Wednesday to withdraw the U.S. from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, we were left to wonder — not for the first time — can he really do that?

The UNFCCC is the umbrella organization governing UN-organized climate diplomacy, including the annual climate summit known as the Conference of the Parties and the 2015 Paris Agreement. The U.S. has been in and out and back into the Paris Agreement over the years, and was most recently taken out again by a January 2025 executive order from President Trump. The U.S. has never before attempted to exit the UNFCCC — which, unlike the Paris Agreement, it joined with the advice and consent of the Senate.

Whether or not a president can unilaterally remove the U.S. from a Senate-approved treaty is somewhat uncharted legal territory. As University of Pennsylvania constitutional law professor Jean Galbraith told me, “This is an issue on which the text of the constitution is silent — it tells you how to make a treaty, but it doesn’t tell you anything about how to unmake a treaty.” Even if a president can simply withdraw from a treaty, there’s still the question of what happens next. Could a future president simply rejoin the UFCCC? Or would they again need to seek the advice and consent of the Senate, which would require getting 67 senators to agree that international climate diplomacy is a worthy enterprise? And what does all of this mean for the future of the Paris Agreement? Is the U.S. locked out for good?

In an attempt to wrap my head around these questions, I spoke to both Galbraith and Sue Biniaz, a lecturer at Yale School of the Environment and a former lead climate lawyer at the State Department who worked on both the Paris Agreement and the UNFCCC. Biniaz and Galbraith were part of a 2018 symposium on the question of treaty withdrawal that was prompted, in part, by Trump’s first attempt to remove the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, during his first term in the White House. Those conversations led Galbraith to consider the question of rejoining treaties in a 2020 Virginia Law Review article. Suffice it for now to say that both questions are complicated, but we dig into the answers to both and more in our conversation below.

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

At the most basic level, what are the constitutional questions at play in an executive withdrawal from the UNFCCC?

Galbraith: Typically, the U.S. president needs to think about both international law and domestic law. And as a matter of international law, there is a withdrawal provision in the UNFCCC that says you can withdraw after you’ve been in it for a few years, after one year of notice. Assuming they give their notice of withdrawal and wait a year, this is an issue on which the text of the constitution is silent — it tells you how to make a treaty, but it doesn’t tell you anything about how to unmake a treaty.

And we have no definitive answer from the courts. The closest they got to deciding that was in a case called Goldwater v. Carter, which was when President Carter terminated the mutual defense treaty with Taiwan. That was litigated, and the Supreme Court ducked — four justices said this is a political question that we’re not going to resolve, and one justice said this case is not ripe for resolution because I don’t know whether or not Congress likes the withdrawal. There was no majority opinion, and there was no ruling on the merit for the constitutional question.

Presidents have exercised the authority to withdraw the United States from various international agreements. So in practice, it happens. The constitutionality has not been finally settled.

Both Trump administrations have removed the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, but the Paris Agreement was not a Senate-ratified treaty, whereas the UNFCCC is. How does that change things?

Galbraith: The text of the constitution only clearly spells out one way to make an international treaty, in the treaty clause [of Article II]. When you make an Article II treaty, it’s signed by the president and secretary of state. It goes over to the Senate; the Senate provides advice and consent — the U.S. is still not in it. At that point, the president has to take a final act of ratifying the treaty, which means depositing the instrument of ratification with the international depository, and that’s the moment you’re in. And it’s perfectly permissible for a president after the Senate has given advice and consent not to ratify a treaty, or to leave those resolutions of advice and consent for years and then go ahead and ratify.

In practice, you have all these kinds of other ways of making [a treaty]. You have what happened with the Paris Agreement, where the president does it largely on their own authority, but maybe pointing to pre-existing facts of, say, the UNFCCC’s existence. You have some international agreements that have been negotiated, then taken to Congress rather than to the Senate. Sometimes you have Congress pass a law that says, Please make this kind of agreement. So you have a lot of different pathways to making them. And I think there is a story in which the pathway to making them should be significant in thinking about, what is the legitimate, constitutional way for exiting them?

To me, it’s pretty obvious that if you don’t get specific approval for an agreement in the first place, then you should be able to unilaterally withdraw, assuming you’re doing so consistent with international law. I think the concerns around the constitutionality of withdrawal are more significant for the UNFCCC than they are for the Paris Agreements. But there nonetheless is this fairly strong body of practice in which presidents have viewed themselves as authorized to withdraw without needing to go to Congress or the Senate.

Biniaz: The Senate doesn’t ratify. It sounds like a detail, but the Senate basically authorizes the president to ratify — they give their advice and consent. And that’s important because it’s not the Senate that decides whether we join an agreement. They authorize the president, the president does not have to join. And that becomes relevant when we talk about withdrawing and rejoining.

We did not address, when we sent up the framework convention, whether it was legally necessary to send it to the Senate. But we sent it in any event, and it was approved basically unanimously by the full Senate back in 1992. With respect to the Paris Agreement, there are a lot of different considerations when you’re trying to figure out whether something needs to go to the Senate or not, but the fact that we already had a Senate-approved convention changed the legal calculus as to whether this Paris Agreement needed to go to the Senate. And then when the Paris Agreement ended up essentially elaborating the convention and the targets were not legally binding, we decided we could do it as an executive agreement. There was some quibbling in some quarters — more from a political point of view than a legal point of view — but I didn’t hear any objection from a legal point of view.

Now, in terms of withdrawing from an agreement, whether or not an agreement has been approved by the Senate, my view would be: The president can withdraw unilaterally. That is the mainstream view. It’s certainly the view that the president can withdraw unilaterally from an agreement that didn’t even go to Congress, like the Paris Agreement. And in part, that’s for the reasons that I mentioned. The Senate is not deciding to join the agreement — they’re authorizing, but it’s up to the president whether to actually join, and the president does that unilaterally. And then the mirror image of that would be he or she can withdraw unilaterally.

There’s a related legal question that has not been litigated, which is if Congress passes a law that says, Thou shalt not withdraw from a particular agreement, would that law be constitutional? Some would say no, because the president can withdraw, and so the Congress can’t fetter that right. So that’s like uncharted waters, but that’s not a live issue in this case.

Trump took the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement. Biden put the us back into the Paris Agreement. Trump then took us out of the Paris Agreement again, and is now withdrawing the U.S. from the umbrella organization of the Paris Agreement. I assume that would complicate the efforts of a future president to rejoin the Paris Agreement. Would it be possible for them to rejoin the framework convention? What would have to happen?

Galbraith: So first, the framework convention is the gateway to the Paris Agreement. There’s a provision in the Paris Agreement that says, in order to be in the Paris Agreement, you’ve got to be in the framework convention. And so as a matter of international law, in order to rejoin the Paris Agreement — at least unless it were dramatically amended, which is its own unlikely thing — you would need to be a member of the UNFCCC, which does mean that the question of how you rejoin the UNFCCC becomes significant. We have very little practice on any kind of rejoining. I myself think that the president could simply rejoin the UNFCCC by pointing back to the original Senate resolution of advice and consent to it. You could go back to the Senate. You could ask Congress for a resolution.

My own view is that if the president withdraws the U.S., well, they still have on the books this resolution in which the Senate has consented to ratification — they want to go back in, they go back in. I think this is pretty logically clear, but also an important constraint on presidential power. Because it’s a much more concerning increase in presidential power if you have to do all the work of getting two-thirds of the Senate, then any president can, just at the snap of their fingers, take you out, and you have to go all the way back to the beginning.

Biniaz: There are many options. One is a straightforward option: You go back to the Senate, get 67 votes. Another would be you get both houses of Congress to authorize it [on a majority vote basis]. Another would be — and there may be more — but another would be the idea that the original Senate resolution which we used in 1992 to join still exists, and nothing has extinguished it. And there the analogy would be to a regular law.

There’s several laws in the United States that authorized the president to join some kind of international body or institution. There’s a law that authorizes the president to join the International Labor Organization. There’s a law that authorized the president to join UNESCO. In both of those cases, the U.S. has been in and out and back in — and I think in one case, at least, back out. No one has batted an eye because, well, it’s a law. So the question there would be, is there any reason why a Senate resolution would be any different? Professor Galbraith explores in her law review article that exact question, and concludes that, no, there shouldn’t be a difference — I’m simplifying, but that’s the gist. And under that theory, yeah, a future president could rejoin the convention on his or her own, utilizing that authority, and then after having rejoined the convention, rejoin the Paris Agreement.

So you mentioned that there’s a provision in the UNFCCC that says you have to give notice that you’re exiting, and you wait a year, and then you exit. What does not waiting a year look like?

Galbraith: It can happen that an entity will announce its exit and then violate international law by violating the treaty terms during that one-year period. If there are, say, reporting obligations that the United States has, it would be a violation of international law not to meet those during the period while you’re still a party to the treaty.

This is obviously an escalation of Trump’s previous actions to withdraw from the Paris Agreement, in the sense that it cuts off the path to rejoining that. What does this tell us about the way the Trump administration views its position within global climate diplomacy, and also the international community, period?

Galbraith: It adds to the impression that we already see other contexts, which is that the second Trump administration is even less inhibited and climate-aware than the first administration was — which is really saying something, right? This is an escalation of a position that was already an international outlier. Every other country is in these things, and it shows a real, powerful, and deeply upsetting failure to address the crisis of the global commons.

Biniaz: The way I think about it is that, during Trump 1, it was more like there was an absence of a positive — so in other words, the administration continued to participate in negotiations. They were not pressing countries to take climate action, but neither were they pressing countries not to take climate action. This administration, you could think of it as not just the absence of a positive, but the presence of a negative. I don’t mean that in any judgmental sense. I just mean there’s been much more of an active push from the administration for others to sort of follow suit or to vote against climate-related agreements such as at the [International Maritime Organization]. That’s quite a difference between 1 and 2.

Going into this past year’s COP, it seemed like there was already a sense that international climate diplomacy was, if not dead, at least the wind had come out of the sails. Do you agree? And if so, do you think that wind will come back?

Biniaz: You have to think of international climate diplomacy very broadly. It’s not just the UNFCCC Paris Agreement and decisions that are taken by consensus. That was pretty thin gruel that came out of COP30. But if you think of international climate diplomacy more broadly as all kinds of initiatives, coalitions that are operating among subgroups of countries and at all levels of stakeholders, there’s really a lot going on in what people call the real world. I think over the next couple of years, the proportion of action that’s taken officially, by consensus, dips somewhat, and action goes up. And maybe that balance shifts over time. But I think it’s wrong to judge climate diplomacy simply by what was achievable by 197 countries, because that’s always going to be the hardest to achieve, with or without the United States.

I think it’s more difficult without a pro-climate U.S. because of the role the U.S. has historically played, in terms of promoting ambition and brokering compromises and that kind of thing. But I don’t think, if you only look at that, it’s not the right metric for judging all of global climate diplomacy.

On Venezuela’s oil, permitting reform, and New York’s nuclear plans

Current conditions: Cold temperatures continue in Europe, with thousands of flights canceled at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, while Scotland braces for a winter storm • Northern New Mexico is anticipating up to a foot of snow • Australia continues to swelter in heat wave, with “catastrophic fire risk” in the state of Victoria.

The White House said in a memo released Wednesday that it would withdraw from more than 60 intergovernmental organizations, including the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the international climate community’s governing organization for more than 30 years. After a review by the State Department, the president had determined that “it is contrary to the interests of the United States to remain a member of, participate in, or otherwise provide support” to the organizations listed. The withdrawal “marks a significant escalation of President Trump’s war on environmental diplomacy beyond what he waged in his first term,” Heatmap’s Robinson Meyer wrote Wednesday evening. Though Trump has pulled the United States out of the Paris Agreement (twice), he had so far refused to touch the long-tenured UNFCCC, a Senate-ratified pact from the early 1990s of which the U.S. was a founding member, which “has served as the institutional skeleton for all subsequent international climate diplomacy, including the Paris Agreement,” Meyer wrote.

Among the other organizations named in Trump’s memo was the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which produces periodic assessments on the state of climate science. The IPCC produced the influential 2018 report laying the intellectual foundations for the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.

More details are emerging on the Trump administration’s plan to control Venezuela’s oil assets. Trump posted Tuesday evening on Truth Social that the U.S. government would take over almost $3 billion worth of Venezuelan oil. On Wednesday, Secretary of Energy Chris Wright told a Goldman Sachs energy conference that “going forward we will sell the production that comes out of Venezuela into the marketplace.” A Department of Energy fact sheet laid out more information, including that “all proceeds from the sale of Venezuelan crude oil and oil products will first settle in U.S. controlled accounts,” and that “these funds will be disbursed for the benefit of the American people and the Venezuelan people at the discretion of the U.S. government.” The DOE also said the government would selectively lift some sanctions to enable the oil sales and transport and would authorize importation of oil field equipment.

As I wrote for Heatmap on Monday, sanctions are just one barrier to oil development among a handful that would have to be cleared for U.S. oil companies to begin exploiting Venezuela’s vast oil resources.

In a Senate floor speech, Senator Martin Heinrich of New Mexico blasted the Trump administration’s anti-renewables executive actions, saying that the U.S. is “facing an energy crisis of the Trump administration’s own making,” and that “the Trump administration is dismantling the permitting process that we use to build new energy projects and get cheaper electrons on the grid.” Heinrich, a Democrat, is the ranking member of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources and a key player in any possible permitting reform bill. Though he said he supports permitting reform in principle, calling for “a system that can reliably get to a ‘yes’ or a ‘no’ on a permit in two to three years — not 10, not 17,” he said that “any permitting deal is going to have to guarantee that no administration of either party can weaponize the permitting process for cheap political points.” Heinrich called on Trump officials “to follow the law. They need to reverse their illegal stop work orders, and they need to start approving legally compliant energy projects.”

He did offer an olive branch to the Republican senators with whom he would have to negotiate on any permitting legislation, noting that “the challenge to doing permitting reform is not in this building,” specifying that Senators Mike Lee, chair of the ENR Committee, and Shelly Moore-Capito, chair of the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, have not been barriers to a deal. Instead, he said, “it is this Administration that is poisoning the well.”

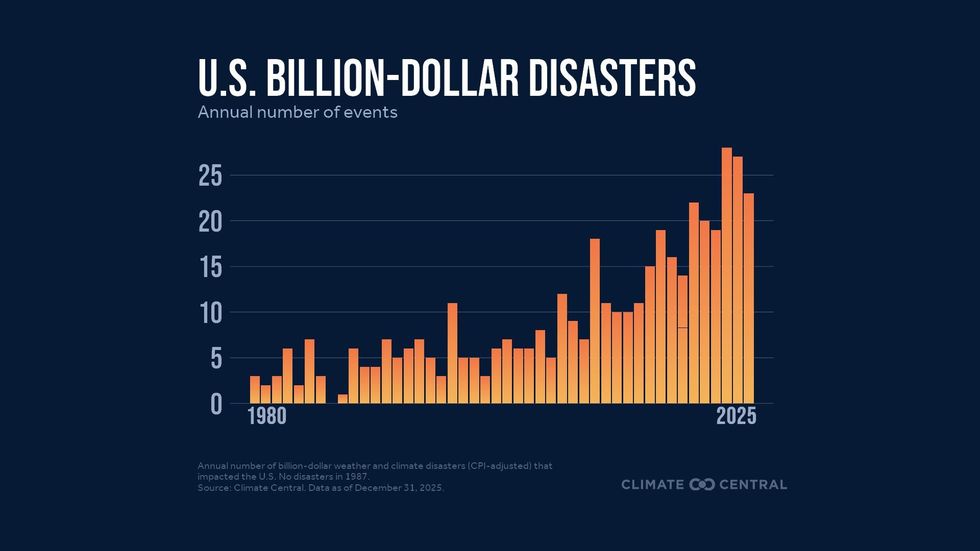

The climate science nonprofit Climate Central released an analysis Thursday morning ranking 2025 “as the third-highest year (after 2023 and 2024) for billion-dollar weather and climate disasters — with 23 such events causing 276 deaths and costing a total of $115 billion in damages,” according to a press release.

Going back to 1980, the average number of disasters costing $1 billion or more to clean up was nine, with an average total bill of $67.9 billion. The U.S. hit that average within the first weeks of last year with the Los Angeles wildfires, which alone were responsible for over $61 billion in damages, the most economically damaging wildfire on record.

The New York Power Authority announced Wednesday that 23 “potential developers or partners,” including heavyweights like NextEra and GE Hitachi and startups like The Nuclear Company and Terra Power, had responded to its requests for information on developing advanced nuclear projects in New York State. Eight upstate communities also responded as potential host sites for the projects.

New York Governor Kathy Hochul said last summer that New York’s state power agency would go to work on developing 1 gigawatt of nuclear capacity upstate. Late last year, Hochul signed an agreement with Ontario Premier Doug Ford to collaborate on nuclear technology. Ontario has been working on a small modular reactor at its existing Darlington nuclear site, across Lake Ontario from New York.

“Sunrise Wind has spent and committed billions of dollars in reliance upon, and has met the requests of, a thorough review process,” Orsted, the developer of the Sunrise Wind project off the coast of New York, said in a statement announcing that it was filing for a preliminary injunction against the suspension of its lease late last year.

The move would mark a significant escalation in Trump’s hostility toward climate diplomacy.

The United States is departing the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the overarching treaty that has organized global climate diplomacy for more than 30 years, according to the Associated Press.

The withdrawal, if confirmed, marks a significant escalation of President Trump’s war on environmental diplomacy beyond what he waged in his first term.

Trump has twice removed the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, a largely nonbinding pact that commits the world’s countries to report their carbon emissions reduction goals on a multi-year basis. He most recently did so in 2025, after President Biden rejoined the treaty.

But Trump has never previously touched the UNFCCC. That older pact was ratified by the Senate, and it has served as the institutional skeleton for all subsequent international climate diplomacy, including the Paris Agreement.

The United States was a founding member of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. It first joined the treaty in 1992, when President George H.W. Bush signed the pact and lawmakers unanimously ratified it.

Every other country in the world belongs to the UNFCCC. By withdrawing from the treaty, the U.S. would likely be locked out of the Conference of the Parties, the annual UN summit on climate change. It could also lose any influence over UN spending to drive climate adaptation in developing countries.

It remains unclear whether another president could rejoin the framework convention without a Senate vote.

As of 6 p.m. Eastern on Wednesday, the AP report cited a U.S. official who spoke on condition of anonymity because the news had not yet been announced.

The Trump administration has yet to confirm the departure. On Wednesday afternoon, the White House posted a notice to its website saying that the U.S. would leave dozens of UN groups, including those that “promote radical climate policies,” without providing specifics. The announcement was taken down from the White House website after a few minutes.

The White House later confirmed the departure from 31 UN entities in a post on the social network X, but did not list the groups in question.