You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Election season is about to heat up — literally. The question is whether voters will care.

Of the 158 days left to go before the presidential election, 94 of them will fall during the summer. Such an alignment is not entirely a coincidence — the 29th U.S. Congress designated the first Tuesday in November for voting in order to avoid summer planting and the autumn harvest — but in 2024, the overlap between the hottest months of the year and the feverish finale of the presidential campaign is especially apropos.

Fire agencies have warned of an “above average” wildfire season in the Southwest, northern Great Lakes, northern Great Basin, and Hawaii. Last week, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration issued the most active hurricane outlook in its history. The western Great Plains and the intermountain West are in a worsening drought. Forecasters at AccuWeather predicted widespread heat waves over much of the eastern and southern United States in the coming months. Emergency managers are bracing for the “new normal” of deadly summer rainfall.

But will a wet, hot, climate change-driven summer be enough to tilt the election in someone’s favor?

We know that climate-related issues can swing elections — clean air and water, cheap energy, and creating new high-paying jobs all poll exceptionally well. Voter interest tends to drop off, however, when these things are framed as climate issues. And on the darker flip side, the realities of living in a hotter world, including “unchecked migration, economic stagnation, and the loss of homeland,” are “precisely the kind of developments that have historically fomented authoritarian sentiments,” Justin Worland argued in Time earlier this year. Donald Trump, meanwhile, has repeatedly proved eager to go toe-to-toe with President Joe Biden on things like clean energy, electric vehicles, and climate science.

But how much extreme weather events themselves could swing the November election is far less clear. Research suggests that even living through a traumatic event like a wildfire or hurricane isn’t necessarily enough to convert you into a climate voter. “Experience matters, but I don’t know that it matters in the way that people wishcast it to,” Matto Mildenberger, a political scientist at the University of California, Santa Barbara who has studied the relationship between proximity to wildfires and pro-environmental voting, told me.

As Mildenberger explained, “In order to experience a wildfire or a heat wave or a flood and have that galvanize you into wanting to see more ambitious climate action, you’d have to experience and understand yourself as a victim of climate change.” For decades, fossil fuel interests have worked to undermine the scientific narrative and cast doubt on the links between extreme weather and climate, which is why even Republicans who experience disasters firsthand still “fall back onto stories about how there have always been wildfires, there have always been droughts.”

In other words, this is not a chicken-or-egg enigma. How voters already think about climate change is what shapes their ensuing narratives about disasters. Peter Howe, a professor of geography at Utah State University who studies public perceptions of climate change, conducted a survey of research on behavioral outcomes in relation to extreme weather that reinforced this idea. He found that “extreme weather may reinforce opinions among people who are already worried about climate change, yet be misattributed or misperceived by those who are unconcerned.”

There is evidence that linking climate change with extreme weather could actually backfire at the ballot box for green-minded candidates. A 2022 study led by Rebecca Perlman, a professor of political science at the University of California, Berkeley, found that Republicans who saw references to climate change after a wildfire became less likely to support an energy tax that would “protect against future wildfires and other natural disasters.” Concerningly, this pattern even showed up (albeit with “weaker and generally nonsignificant effects”) among Democrats and Independents, leading Perlman and her coauthor to suggest that “on the margin, attributing weather-related natural disasters to climate change may be a losing political proposition with voters.”

Perlman confirmed that she would be “surprised” if extreme summer weather had “much impact on voting at the national level” when I reached her via email. But that “doesn’t mean it will be precisely zero,” she went on.

Mildenberger made a similar point. Though a hurricane or a wildfire is unlikely to peel Republican voters away from Trump (and might even push some deeper into his arms), if you take a more regional lens, then you could “easily expect extreme weather events to reshape how people are prioritizing their vote, or their likelihood of volunteering, or how they’re talking to their friends and family about the current administration.”

But while hurricanes, droughts, wildfires, and heat waves can confirm Democratic priors and motivate liberals who wouldn’t otherwise have voted, Matthew Burgess, a professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado, Boulder, warned me against lumping all conservatives together as uniformly undisturbed. “Even deep red parts of Colorado get worried about drought and water scarcity,” he pointed out.

Burgess’ research has found that Independents and liberal-to-moderate Republicans worry about climate change only slightly less than moderate-to-conservative liberals do; it’s conservative Republicans who are set far apart from the rest of the electorate, sometimes skewing results. In other words, while many studies look at extreme weather events and climate change attribution and frame the results as Republicans versus Democrats, the actual split in how voters interpret extreme weather events might be better framed as between the most conservative Republicans and everyone else.

The bigger question, in Burgess’s mind, is whether extreme weather could ever rival issues like crime or inflation, which generally affect a greater portion of the electorate, for a place in voters’ hearts. “If you had a really big natural disaster that directly affects a broad swath of people, and whose link to climate change is really clear — that would be the type of thing I would expect to have an effect” on voters, Burgess said.

Admittedly, it’s scary to imagine what exactly that event might be. A massive wildfire season with smoke that blankets the entire country or breaks out in a place we don’t expect? Hurricanes that pummel both the East Coast and the West Coast? So much flooding that whirlpools appear in the streets of American cities? Or something we haven’t already experienced and maybe haven’t even anticipated?

If there were ever a summer to find out, it’d be this one. It’s another “hottest year ever” on Planet Earth, and even if Americans don’t ultimately vote like it, that truth will remain.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

1. Marion County, Indiana — State legislators made a U-turn this week in Indiana.

2. Baldwin County, Alabama — Alabamians are fighting a solar project they say was dropped into their laps without adequate warning.

3. Orleans Parish, Louisiana — The Crescent City has closed its doors to data centers, at least until next year.

A conversation with Emily Pritzkow of Wisconsin Building Trades

This week’s conversation is with Emily Pritzkow, executive director for the Wisconsin Building Trades, which represents over 40,000 workers at 15 unions, including the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, the International Union of Operating Engineers, and the Wisconsin Pipe Trades Association. I wanted to speak with her about the kinds of jobs needed to build and maintain data centers and whether they have a big impact on how communities view a project. Our conversation was edited for length and clarity.

So first of all, how do data centers actually drive employment for your members?

From an infrastructure perspective, these are massive hyperscale projects. They require extensive electrical infrastructure and really sophisticated cooling systems, work that will sustain our building trades workforce for years – and beyond, because as you probably see, these facilities often expand. Within the building trades, we see the most work on these projects. Our electricians and almost every other skilled trade you can think of, they’re on site not only building facilities but maintaining them after the fact.

We also view it through the lens of requiring our skilled trades to be there for ongoing maintenance, system upgrades, and emergency repairs.

What’s the access level for these jobs?

If you have a union signatory employer and you work for them, you will need to complete an apprenticeship to get the skills you need, or it can be through the union directly. It’s folks from all ranges of life, whether they’re just graduating from high school or, well, I was recently talking to an office manager who had a 50-year-old apprentice.

These apprenticeship programs are done at our training centers. They’re funded through contributions from our journey workers and from our signatory contractors. We have programs without taxpayer dollars and use our existing workforce to bring on the next generation.

Where’s the interest in these jobs at the moment? I’m trying to understand the extent to which potential employment benefits are welcomed by communities with data center development.

This is a hot topic right now. And it’s a complicated topic and an issue that’s evolving – technology is evolving. But what we do find is engagement from the trades is a huge benefit to these projects when they come to a community because we are the community. We have operated in Wisconsin for 130 years. Our partnership with our building trades unions is often viewed by local stakeholders as the first step of building trust, frankly; they know that when we’re on a project, it’s their neighbors getting good jobs and their kids being able to perhaps train in their own backyard. And local officials know our track record. We’re accountable to stakeholders.

We are a valuable player when we are engaged and involved in these sting decisions.

When do you get engaged and to what extent?

Everyone operates differently but we often get engaged pretty early on because, obviously, our workforce is necessary to build the project. They need the manpower, they need to talk to us early on about what pipeline we have for the work. We need to talk about build-out expectations and timelines and apprenticeship recruitment, so we’re involved early on. We’ve had notable partnerships, like Microsoft in southeast Wisconsin. They’re now the single largest taxpayer in Racine County. That project is now looking to expand.

When we are involved early on, it really shows what can happen. And there are incredible stories coming out of that job site every day about what that work has meant for our union members.

To what extent are some of these communities taking in the labor piece when it comes to data centers?

I think that’s a challenging question to answer because it varies on the individual person, on what their priority is as a member of a community. What they know, what they prioritize.

Across the board, again, we’re a known entity. We are not an external player; we live in these communities and often have training centers in them. They know the value that comes from our workers and the careers we provide.

I don’t think I’ve seen anyone who says that is a bad thing. But I do think there are other factors people are weighing when they’re considering these projects and they’re incredibly personal.

How do you reckon with the personal nature of this issue, given the employment of your members is also at stake? How do you grapple with that?

Well, look, we respect, over anything else, local decision-making. That’s how this should work.

We’re not here to push through something that is not embraced by communities. We are there to answer questions and good actors and provide information about our workforce, what it can mean. But these are decisions individual communities need to make together.

What sorts of communities are welcoming these projects, from your perspective?

That’s another challenging question because I think we only have a few to go off of here.

I would say more information earlier on the better. That’s true in any case, but especially with this. For us, when we go about our day-to-day activities, that is how our most successful projects work. Good communication. Time to think things through. It is very early days, so we have some great success stories we can point to but definitely more to come.

The number of data centers opposed in Republican-voting areas has risen 330% over the past six months.

It’s probably an exaggeration to say that there are more alligators than people in Colleton County, South Carolina, but it’s close. A rural swath of the Lowcountry that went for Trump by almost 20%, the “alligator alley” is nearly 10% coastal marshes and wetlands, and is home to one of the largest undeveloped watersheds in the nation. Only 38,600 people — about the population of New York’s Kew Gardens neighborhood — call the county home.

Colleton County could soon have a new landmark, though: South Carolina’s first gigawatt data center project, proposed by Eagle Rock Partners.

That’s if it overcomes mounting local opposition, however. Although the White House has drummed up data centers as the key to beating China in the race for AI dominance, Heatmap Pro data indicate that a backlash is growing from deep within President Donald Trump’s strongholds in rural America.

According to Heatmap Pro data, there are 129 embattled data centers located in Republican-voting areas. The vast majority of these counties are rural; just six occurred in counties with more than 1,000 people per square mile. That’s compared with 93 projects opposed in Democratic areas, which are much more evenly distributed across rural and more urban areas.

Most of this opposition is fairly recent. Six months ago, only 28 data centers proposed in low-density, Trump-friendly countries faced community opposition. In the past six months, that number has jumped by 95 projects. Heatmap’s data “shows there is a split, especially if you look at where data centers have been opposed over the past six months or so,” says Charlie Clynes, a data analyst with Heatmap Pro. “Most of the data centers facing new fights are in Republican places that are relatively sparsely populated, and so you’re seeing more conflict there than in Democratic areas, especially in Democratic areas that are sparsely populated.”

All in all, the number of data centers that have faced opposition in Republican areas has risen 330% over the past six months.

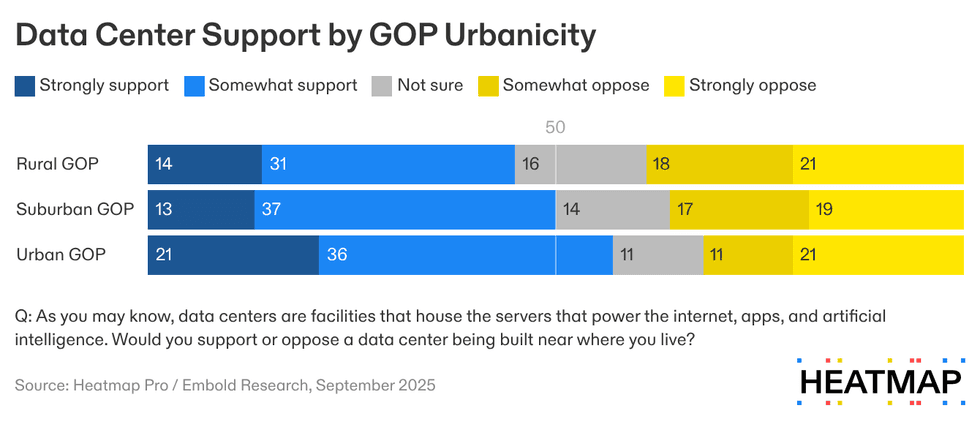

Our polling reflects the breakdown in the GOP: Rural Republicans exhibit greater resistance to hypothetical data center projects in their communities than urban Republicans: only 45% of GOP voters in rural areas support data centers being built nearby, compared with nearly 60% of urban Republicans.

Such a pattern recently played out in Livingston County, Michigan, a farming area that went 61% for President Donald Trump, and “is known for being friendly to businesses.” Like Colleton County, the Michigan county has low population density; last fall, hundreds of the residents of Howell Township attended public meetings to oppose Meta’s proposed 1,000-acre, $1 billion AI training data center in their community. Ultimately, the uprising was successful, and the developer withdrew the Livingston County project.

Across the five case studies I looked at today for The Fight — in addition to Colleton and Livingston Counties, Carson County, Texas; Tucker County, West Virginia; and Columbia County, Georgia, are three other red, rural examples of communities that opposed data centers, albeit without success — opposition tended to be rooted in concerns about water consumption, noise pollution, and environmental degradation. Returning to South Carolina for a moment: One of the two Colleton residents suing the county for its data center-friendly zoning ordinance wrote in a press release that he is doing so because “we cannot allow” a data center “to threaten our star-filled night skies, natural quiet, and enjoyment of landscapes with light, water, and noise pollution.” (In general, our polling has found that people who strongly oppose clean energy are also most likely to oppose data centers.)

Rural Republicans’ recent turn on data centers is significant. Of 222 data centers that have faced or are currently facing opposition, the majority — 55% —are located in red low-population-density areas. Developers take note: Contrary to their sleepy outside appearances, counties like South Carolina’s alligator alley clearly have teeth.