You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

Those 21-inch rims — and America’s opulent car culture — are doing more harm than good.

The biggest complaint drivers have about electric vehicles is their range. They might be far cleaner, much cheaper to operate and maintain, and not subsidize murderous dictators, but they can typically go only 200-350 miles on a charge (though some expensive models can top 500 miles). And because the U.S. car charging network is still being built out, that can mean having to carefully plan one’s road trip, having to wait in line at a charger, and so on.

So it’s strange that so many EVs are outfitted with snazzy features that badly sap their range. In particular, the fancy low-profile rims that are very common on American EVs knock their range down by as much as 15 percent. It’s just the most obvious example of how America’s addiction to big, fast cars is an unnecessary obstacle to the EV transition.

Jason Fensky explains the physics of the rim problem at Engineering Explained. All else equal, larger diameter wheels are heavier, which means more rotating mass, which means more energy needed to spin them. A larger diameter means more air resistance (particularly when they come with fancy angular decorations), and more resistance still because they typically come with wider tires. Wider tires in turn worsen rolling resistance, eating up still more energy. According to Tesla, moving from 20-inch rims to 18-inch ones on a Model 3 improves range by nearly 15 percent, under typical conditions.

This matters especially for EVs because batteries are considerably less energy-dense than diesel or gasoline. (Their range is as good as it is because electric motors are vastly more efficient than internal combustion engines.) Where you can compensate easily enough for inefficient wheels in a gas-powered car by adding a couple gallons to the fuel tank, additional battery capacity means a huge weight penalty, which itself saps range.

What’s more, low-profile tires have a considerably worse ride quality because there is less rubber to absorb shocks, and with no protruding sidewall, it’s very easy to damage those fancy rims when parking or driving too close to a curb.

The problem is compounded by the EV manufacturer habit of producing absurdly fast models. Zero-to-60 times for today’s crop of electric automobiles are routinely under five seconds and occasionally at three seconds or less. Now, I can’t blame people for enjoying the thrill of explosive electric acceleration — it’s surely one of the reasons EVs have gained market share — but that is preposterous speed. Sixty miles per hour in three seconds is faster than a 2020 Ferrari Portofino, equipped with a twin-turbocharged V8 making 591 horsepower.

We can see all these problems coming together with the Rivian R1T. This pickup truck starts with a dual-motor setup making “only” 600 horsepower and a 0-60 times of 4.5 seconds, with a range of 270 miles on the base battery. You can increase the range to 350 miles with the medium battery, and 400 miles with the biggest one. But if you option the quad-motor drivetrain making 835 horsepower with the medium battery (the only option available at time of writing) range is cut from 350 to 328 miles. And sure enough, if you pick the 21-inch wheels instead of the 20-inch, range is cut again to 303 miles.

Those battery upgrades are also extremely expensive, because they’re so large. The base battery is 105 kilowatt-hours, while the medium is 135 and the large 180 kilowatt-hours, and so the different options will set you back $6,000 and $16,000 respectively. That huge battery is also why the R1T has a base curb weight of over 7,000 pounds.

The R1T has gotten rave reviews because of its ridiculous speed and high build quality. But it is Caligula-esque levels of pointless excess to be driving a large truck around that is faster than a Ferrari sports car. Let’s be real: In ordinary road conditions nobody ever has a legitimate need to hit 60 miles per hour in three seconds. People who even use that capability outside of a race track are in the best case scenario impressing their friends on a highway on-ramp, or else they are breaking the law somehow.

It should also be noted that the heavier a car is, the more dangerous it is to other cars or pedestrians in an accident, because momentum is proportional to mass.

This isn’t the only way to go, of course. Consider the recently discontinued Chevy Bolt, with a 200 horsepower motor and a 63 kilowatt-hour battery. But that smaller drivetrain and battery means its weight comes in under 3,600 pounds, which together with relatively sensible 17-inch wheels (though I’d go even smaller) enables a perfectly respectable range of 259 miles. (That’s just 30 miles short of the Hummer EV, whose battery is 3.4 times larger.) Smaller and cheaper parts also mean the Bolt’s starting price is also $27,500, compared to the R1T’s $74,000 — and because the Bolt requires far less energy and fewer raw materials to produce, it is far better for the climate.

American drivers are simply spoiled by technology. Two hundred horsepower and 266 pound-feet of torque is plenty for 95 percent of the tasks American drivers actually perform with their cars — indeed, more than is strictly necessary. I remember when my family bought a Honda Accord in 2003, with its 160 horsepower four-cylinder engine, and it felt downright zippy.

It will take more than an article to cure America’s addiction to big cars. But right now, EV shoppers can take a simple and easy step to ease their range anxiety: skip the fancy wide rims.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

With policy chaos and disappearing subsidies in the U.S., suddenly the continent is looking like a great place to build.

Europe has long outpaced the U.S. in setting ambitious climate targets. Since the late 2000s, EU member states have enacted both a continent-wide carbon pricing scheme as well as legally binding renewable energy goals — measures that have grown increasingly ambitious over time and now extend across most sectors of the economy.

So of course domestic climate tech companies facing funding and regulatory struggles are now looking to the EU to deploy some of their first projects. “This is about money,” Po Bronson, a managing director at the deep tech venture firm SOSV told me. “This is about lifelines. It’s about where you can build.” Last year, Bronson launched a new Ireland-based fund to support advanced biomanufacturing and decarbonization startups open to co-locating in the country as they scale into the European market. Thus far, the fund has invested in companies working to make emissions-free fertilizers, sustainable aviation fuel, and biofuel for heavy industry.

It’s still rare to launch a fund abroad, and yet a growing number of U.S. companies and investors are turning to Europe to pilot new technology and validate their concepts before scaling up in more capital-constrained domestic markets.

Europe’s emissions trading scheme — and the comparably stable policy environment that makes investors confident it will last — gives emergent climate tech a greater chance at being cost competitive with fossil fuels. For Bronson, this made building a climate tech portfolio somewhere in Europe somewhat of a no-brainer. “In Europe, the regulations were essentially 10 years ahead of where we wanted the Americas and the Asias to be,” Bronson told me. “There were stricter regulations with faster deadlines. And they meant it.”

Of the choice to locate in Ireland, SOSV is in many ways following a model piloted by tech giants Google, Microsoft, Apple, and Meta, all of which established an early presence in the country as a gateway to the broader European market. Given Ireland’s English-speaking population, low corporate tax rate, business-friendly regulations, and easy direct flights to the continent, it’s a sensible choice — though as Bronson acknowledged, not a move that a company successfully fundraising in the U.S. would make.

It can certainly be tricky to manage projects and teams across oceans, and U.S. founders often struggle to find overseas talent with the level of technical expertise and startup experience they’re accustomed to at home. But for the many startups struggling with the fundraising grind, pivoting to Europe can offer a pathway for survival.

It doesn’t hurt that natural gas — the chief rival for many clean energy technologies — is quite a bit more expensive in Europe, especially since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022. “A lot of our commercial focus today is in Europe because the policy framework is there in Europe, and the underlying economics of energy are very different there,” Raffi Garabedian, CEO of Electric Hydrogen, told me. The company builds electrolyzers that produce green hydrogen, a clean fuel that can replace natural gas in applications ranging from heavy industry to long-haul transport.

But because gas is so cheap in the U.S., the economics of the once-hyped “hydrogen economy” have gotten challenging as policy incentives have disappeared. With natural gas in Texas hovering around $3 per thousand cubic feet, clean hydrogen just can’t compete. But “you go to Spain, where renewable power prices are comparable to what they are in Texas, and yet natural gas is eight bucks — because it’s LNG and imported by pipeline — it’s a very different context,” Garabedian explained.

Two years ago, the EU adopted REDIII — the third revision of its Renewable Energy Directive — which raises the bloc’s binding renewable share target to 42.5% by 2030 and broadens its scope to cover more sectors, including emissions from industrial processes and buildings. It also sets new rules for hydrogen, stipulating that by 2030, at least 42% of the hydrogen used for industrial processes such as steel or chemical production must be green — that is, produced using renewable electricity — increasing to 60% by 2035.

Member countries are now working to transpose these continent-wide regulations into national law, a process Garabedian expects to be finalized by the end of this year or early next. Then, he told me, companies will aim to scale up their projects to ensure that they’re operational by the 2030 deadline. Considering construction timelines, that “brings you to next year or the year after for when we’re going to see offtakes signed at much larger volumes,” Garabedian explained. Most European green hydrogen projects are aiming to help decarbonize petroleum, petrochemical, and biofuel refining, of all things, by replacing hydrogen produced via natural gas.

But that timeline is certainly not a given. Despite its many incentives, Europe has not been immune to the rash of global hydrogen project cancellations driven by high costs and lower than expected demand. As of now, while there are plenty of clean hydrogen projects in the works, only a very small percent have secured binding offtake agreements, and many experts disagree with Garabedian’s view that such agreements are either practical or imminent. Either way, the next few years will be highly determinative.

The thermal battery company Rondo Energy is also looking to the continent for early deployment opportunities, the startup’s Chief Innovation Officer John O’Donnell told me, though it started off close to home. Just a few weeks ago, Rondo turned on its first major system at an oil field in Central California, where it replaced a natural gas-powered boiler with a battery that charges from an off-grid solar array and discharges heat directly to the facility.

Much of the company’s current project pipeline, however, is in Europe, where it’s planning to install its batteries at a chemical plant in Germany, an industrial park in Denmark, and a brewery in Portugal. One reason these countries are attractive is that their utilities and regulators have made it easier for Rondo’s system to secure electricity at wholesale prices, thus allowing the company to take advantage of off-peak renewable energy rates to charge when energy is cheapest. U.S. regulations don’t readily allow for that.

“Every single project there, we’re delivering energy at a lower cost,” O’Donnell told me. He too cited the high price of natural gas in Europe as a key competitive advantage, pointing to the crippling effect energy prices have had on the German chemical industry in particular. “There’s a slow motion apocalypse because of energy supply that’s underway,” he said.

Europe has certainly proven to be a more welcoming and productive policy environment than the U.S., particularly since May, when the Trump administration cut billions of dollars in grants for industrial decarbonization projects — including two that were supposed to incorporate Rondo’s tech. One $75 million grant was for the beverage company Diageo, which planned to install heat batteries to decarbonize its operations in Illinois and Kentucky. Another $375 million grant was for the chemicals company Eastman, which wanted to use Rondo’s batteries at a plastics recycling plant in Texas.

While nobody knew exactly what programs the Trump administration would target, John Tough, co-founder at the software-focused venture firm Energize Capital, told me he’s long understood what a second Trump presidency would mean for the sector. Even before election night, Tough noticed U.S. climate investors clamming up, and was already working to raise a $430 million fund largely backed by European limited partners. So while 90% of the capital in the firm’s first fund came from the U.S., just 40% of the capital in this latest fund does.

“The European groups — the pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, the governments — the conviction they have is so high in climate solutions that our branding message just landed better there,” Tough told me. He estimates that about a quarter to a third of the firm’s portfolio companies are based in Europe, with many generating a significant portion of their revenue from the European market.

But that doesn’t mean it was easy for Energize to convince European LPs to throw their weight behind this latest fund. Since the American market often sets the tone for the global investment atmosphere, there was understandable concern among potential participants about the performance of all climate-focused companies, Tough explained.

Ultimately however, he convinced them that “the data we’re seeing on the ground is not consistent with the rhetoric that can come from the White House.” The strong performance of Energize’s investments, he said, reveals that utility and industrial customers are very much still looking to build a more decentralized, digitized, and clean grid. “The traction of our portfolio is actually the best it’s ever been, at the exact same time that the [U.S.-based] LPs stopped focusing on the space,” Tough told me.

But Europe can’t be a panacea for all of U.S. climate tech’s woes. As many of the experts I talked to noted, while Europe provides a strong environment for trialing new tech, it often lags when it comes to scale. To be globally competitive, the companies that are turning to Europe during this period of turmoil will eventually need to bring down their costs enough to thrive in markets that lack generous incentives and mandates.

But if Europe — with its infinitely more consistent and definitively more supportive policy landscape — can serve as a test bed for demonstrating both the viability of novel climate solutions and the potential to drive down their costs, then it’s certainly time to go all in. Because for many sectors — from green hydrogen to thermal batteries and sustainable transportation fuels — the U.S. has simply given up.

Current conditions: The Philippines is facing yet another deadly cyclone as Super Typhoon Fung-wong makes landfall just days after Typhoon Kalmaegi • Northern Great Lakes states are preparing for as much as six inches of snow • Heavy rainfall is triggering flash floods in Uganda.

The United Nations’ annual climate conference officially started in Belém, Brazil, just a few hours ago. The 30th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change comes days after the close of the Leaders Summit, which I reported on last week, and takes place against the backdrop of the United States’ withdrawal from the Paris Agreement and a general pullback of worldwide ambitions for decarbonization. It will be the first COP in years to take place without a significant American presence, although more than 100 U.S. officials — including the governor of Wisconsin and the mayor of Phoenix — are traveling to Brazil for the event. But the Trump administration opted against sending a high-level official delegation.

“Somehow the reduction in enthusiasm of the Global North is showing that the Global South is moving,” Corrêa do Lago told reporters in Belém, according to The Guardian. “It is not just this year, it has been moving for years, but it did not have the exposure that it has now.”

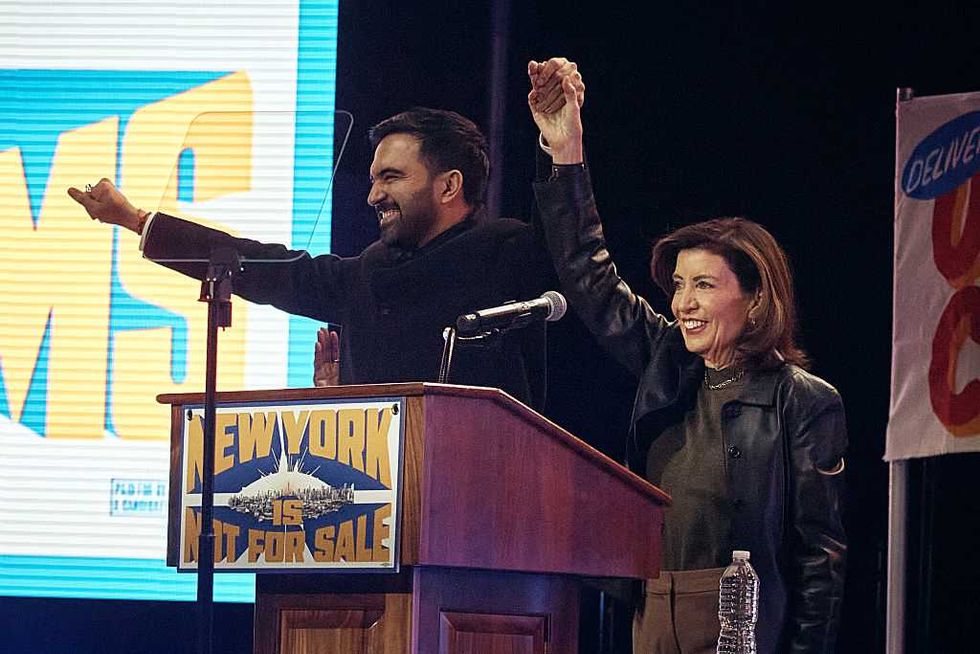

New York regulators approved an underwater gas pipeline, reversing past decisions and teeing up what could be the first big policy fight between Governor Kathy Hochul and New York City Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani. The state Department of Environmental Conservation issued what New York Focus described as crucial water permits for the Northeast Supply Enhancement project, a line connecting New York’s outer borough gas network to the fracking fields of Pennsylvania. The agency had previously rejected the project three times. The regulators also announced that the even larger Constitution pipeline between New York and New England would not go ahead. “We need to govern in reality,” Hochul said in a statement. “We are facing war against clean energy from Washington Republicans, including our New York delegation, which is why we have adopted an all-of-the-above approach that includes a continued commitment to renewables and nuclear power to ensure grid reliability and affordability.”

Mamdani stayed mostly mum on climate and energy policy during the campaign, as Heatmap’s Robinson Meyer wrote, though he did propose putting solar panels on school roofs and came out against the pipeline. While Mamdani seems unlikely to back the pipeline Hochul and President Donald Trump have championed, during a mayoral debate he expressed support for the governor’s plan to build a new nuclear plant upstate.

Late last week, Pine Gate Renewables became the largest clean energy developer yet to declare bankruptcy since Trump and Congress overhauled federal policy to quickly phase out tax credits for wind and solar projects. In its Chapter 11 filings, the North Carolina-based company blamed provisions in Trump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Act that put strict limits on the use of equipment from “foreign entities of concern,” such as China. “During the [Inflation Reduction Act] days, pretty much anyone was willing to lend capital against anyone building projects,” Pol Lezcano, director of energy and renewables at the real estate services and investment firm CBRE, told the Financial Times. “That results in developer pipelines that may or may not be realistic.”

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

The Southwest Power Pool’s board of directors approved an $8.6 billion slate of 50 transmission projects across the grid system’s 14 states. The improvements are set to help the grid meet what it expects to be doubled demand in the next 10 years. The investments are meant to harden the “backbone” of the grid, which the operator said “is at capacity and forecasted load growth will only exacerbate the existing strain,” Utility Dive reported. The grid operator also warned that “simply adding new generation will not resolve the challenges.”

Oil giant Shell and the industrial behemoth Mitsubishi agreed to provide up to $17 million to a startup that plans to build a pilot plant capable of pulling both carbon dioxide and water from the atmosphere. The funding would cover the direct air capture startup Avnos’ Project Cedar. The project could remove 3,000 metric tons of carbon from the atmosphere every year, along with 6,000 tons of clean freshwater. “What you’re seeing in Shell and Mitsubishi investing here is the opportunity to grow with us, to sort of come on this commercialization journey with us, to ultimately get to a place where we’re offering highly cost competitive CO2 removal credits in the market,” Will Kain, CEO of Avnos, told E&E News.

The private capital helps make up for some of the federal funding the Trump administration is expected to cut as part of broad slashes to climate-tech investments. But as Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo reported last month from north of the border, Canada is developing into a hot zone of DAC development.

The future of remote sensing will belong to China. At least, that’s what the research suggests. This broad category involves the use of technologies such as lasers, imagery, and hyperspectral imagery, and is key to everything from autonomous driving to climate monitoring. At least 47% of studies in peer-reviewed publications on remote sensing now originate in China, while just 9% come from the United States, according to the New York University paper. That research clout is turning into an economic advantage. China now accounts for the majority of remote sensing patents filed worldwide. “This represents one of the most significant shifts in global technological leadership in recent history,” Debra Laefer, a professor in the NYU Tandon Civil and Urban Engineering program and the lead author, said in a statement.

The company is betting its unique vanadium-free electrolyte will make it cost-competitive with lithium-ion.

In a year marked by the rise and fall of battery companies in the U.S., one Bay Area startup thinks it can break through with a twist on a well-established technology: flow batteries. Unlike lithium-ion cells, flow batteries store liquid electrolytes in external tanks. While the system is bulkier and traditionally costlier than lithium-ion, it also offers significantly longer cycle life, the ability for long-duration energy storage, and a virtually impeccable safety profile.

Now this startup, Quino Energy, says it’s developed an electrolyte chemistry that will allow it to compete with lithium-ion on cost while retaining all the typical benefits of flow batteries. While flow batteries have already achieved relatively widespread adoption in the Chinese market, Quino is looking to India for its initial deployments. Today, the company announced that it’s raised $10 million from the Hyderabad-based sustainable energy company Atri Energy Transitions to demonstrate and scale its tech in the country.

“Obviously some Trump administration policies have weakened the business case for renewables and therefore also storage,” Eugene Beh, Quino’s founder and CEO, told me when I asked what it was like to fundraise in this environment. “But it’s actually outside the U.S., where the appetite still remains very strong.”

The deployment of battery energy storage in India lags far behind the pace of renewables adoption, presenting both a challenge and an opportunity for the sector. “India does have an opportunity to leapfrog into a more flexible, resilient, and sustainable power system,” Shreyas Shende, a senior research associate at Johns Hopkins’ Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab, told me. The government appears eager to make it happen, setting ambitious targets and offering ample incentives for tech-neutral battery storage deployments, as it looks to lean into novel technologies.

“Indian policymakers have been trying to double down on the R&D and innovation landscape because they’re trying to figure out, how do you reduce dependence on these lithium ion batteries?” Shende said. China dominates the global lithium-ion market, and also has a fractious geopolitical relationship with India, So much like the U.S., India is eager to reduce its dependence on Chinese imports. “Anything that helps you move away from that would only be welcome as long as there’s cost compatibility,” he added

Beh told me that India also presents a natural market for Quino’s expansion, in large part because the key raw material for its proprietary electrolyte chemistry — a clothing dye derived from coal tar — is primarily produced in China and India. But with tariffs and other trade barriers, China poses a much more challenging environment to work in or sell from these days, making the Indian market a simpler choice.

Quino’s dye-based electrolyte is designed to be significantly cheaper than the industry standard, which relies on the element vanadium dissolved in an acidic solution. In vanadium flow batteries, the electrolyte alone can account for roughly 70% of the product’s total cost, Beh said. “We’re using exactly the same hardware as what the vanadium flow battery manufacturers are doing,” he told me minus the most expensive part. “Instead, we use our organic electrolyte in place of vanadium, which will be about one quarter of the cost.”

Like many other companies these days, Beh views data centers as a key market for Quino’s tech — not just because that’s where the money’s at, but also due to one of flow batteries’ core advantages: their extremely long cycle lives. While lithium-ion energy storage systems can only complete from 3,000 to 5,000 cycles before losing 20% or more of their capacity, with flow batteries, the number of cycles doesn’t correlate with longevity at all. That’s because their liquid-based chemistry allows them to charge and discharge without physically stressing the electrodes.

That’s a key advantage for AI data centers, which tend to have spiky usage patterns determined by the time of day and events that trigger surges in web traffic. Many baseload power sources can’t ramp quickly enough to meet spikes in demand, and gas peaker plants are expensive. That makes batteries a great option — especially those that can respond to fluctuations by cycling multiple times per day without degrading their performance.

The company hasn’t announced any partnerships with data center operators to date — though hyperscalers are certainly investing in the Indian market. First up will be getting the company’s demonstration plants online in both California and India. Quino already operates a 100-kilowatt-hour pilot facility near Buffalo, New York, and was awarded a $10 million grant from the California Energy Commission and a $5 million grant from the Department of Energy this year to deploy a larger, 5-megawatt-hour battery at a regional health care center in Southern California. Beh expects that to be operational by the end of 2027.

But its plans in India are both more ambitious and nearer-term. In partnership with Atri, the company plans to build a 150- to 200-megawatt-hour electrolyte production facility, which Beh says should come online next year. With less government funding in the mix, there’s simply less bureaucracy to navigate, he explained. Further streamlining the process is the fact that Atri owns the site where the plant will be built. “Obviously if you have a motivated site owner who’s also an investor in you, then things will go a lot faster,” Beh told me.

The goal for this facility is to enable production of a battery that’s cost-competitive with vanadium flow batteries. “That ought to enable us to enter into a virtuous cycle, where we make something cheaper than vanadium, people doing vanadium will switch to us, that drives more demand, and the cost goes down further,” Beh told me. Then, once the company scales to roughly a gigawatt-hour of annual production, he expects it will be able to offer batteries with a capital cost roughly 30% lower than lithium-ion energy storage systems.

If it achieves that target, in theory at least, the Indian market will be ready. A recent analysis estimates that the country will need 61 gigawatts of energy storage capacity by 2030 to support its goal of 500 gigawatts of clean power, rising to 97 gigawatts by 2032. “If battery prices don’t fall, I think the focus will be towards pumped hydro,” Shende told me. That’s where the vast majority of India’s energy storage comes from today. “But in case they do fall, I think battery storage will lead the way.”

The hope is that by the time Quino is producing at scale overseas, demand and investor interest will be strong enough to support a large domestic manufacturing plant as well. “In the U.S., it feels like a lot of investment attention just turned to AI,” Beh told me, explaining that investors are taking a “wait and see” approach to energy infrastructure such as Quino. But he doesn’t see that lasting. “I think this mega-trend of how we generate and use electricity is just not going away.”