You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

This transcript has been automatically generated.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Robinson Meyer:

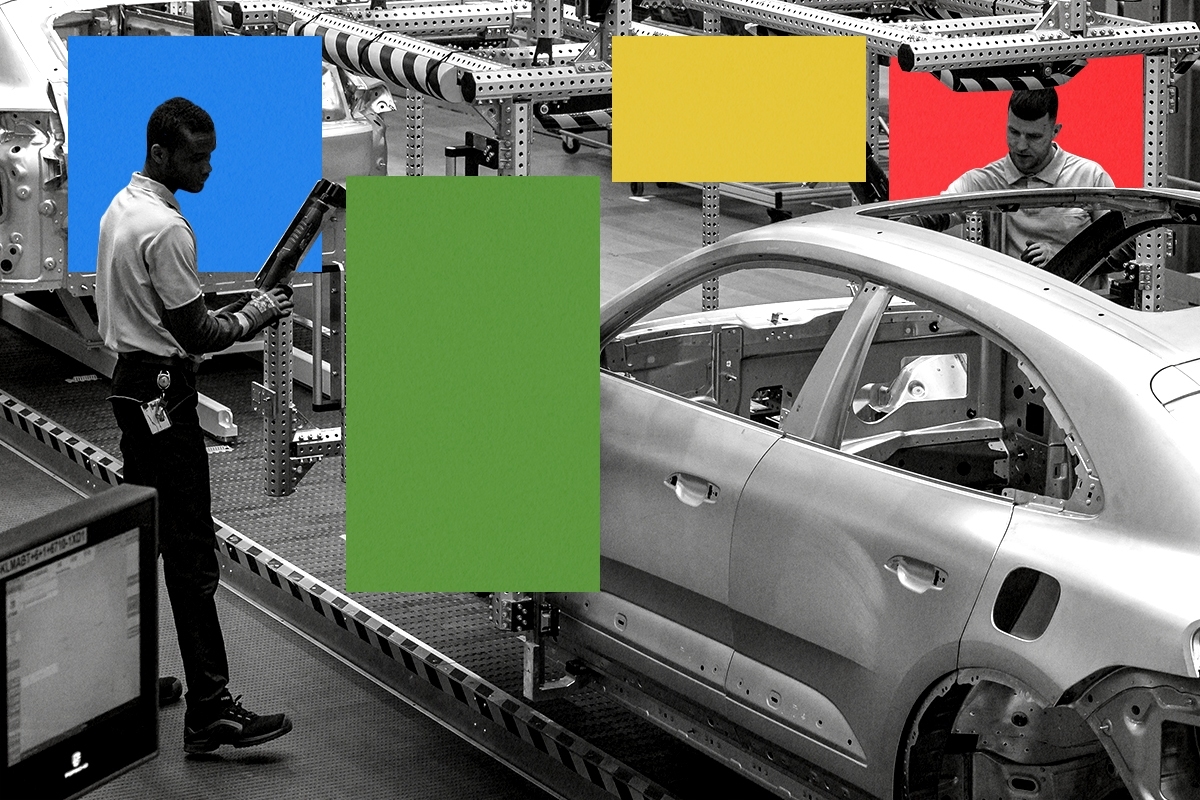

[1:25] It is Friday, February 20. The Trump administration made two big changes at the Environmental Protection Agency last week. The first, which we talked about last show, was that it revoked the endangerment finding, which is the key legal document that allows the EPA to regulate carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. The second is that it revoked what are sometimes called the clean car rules. These are the EPA’s greenhouse gas rules for cars and light-duty trucks. Now, this second change was a big deal, and in some ways, I think a bigger deal than maybe the amount of attention that it got. Because it’s part of a multi-front war on fuel efficiency standards from the Trump administration. It maybe hasn’t gotten a lot of attention, but by the end of this year, the U.S. Will probably not regulate fuel mileage or vehicle efficiency in any way. We’ll essentially be back to the days of the early George W. Bush administration, when automakers could sell as many Hummers as they wanted. Now, the repeal effort legally from Trump relies on a number of economic arguments. The most important of these is the EPA’s argument that it will save the public more money than it costs to roll these rolls back. The EPA says we’ll get about $1.3 trillion worth of benefits from this rollback. Now some of the assumptions behind this finding are contested and some are ideological. Some are, I think, wrong.

Robinson Meyer:

[2:41] Some are just outdated. So today, I wanted to talk to an economist about one of the most important claims in the Trump repeal and why it is no longer in touch with the economics literature.

Robinson Meyer:

[2:51] We’ll also chat about the broader set of economic arguments the Trump administration is making. Our guest today is Ken Gillingham. He’s a professor of economics at Yale and a former senior economist for energy and the environment at the White House Council of Economic Advisors. My conversation with him is coming up. And then in the back half of the show, I talked to Hannah Hess, an associate director at the Rhodium Group about new data on how clean energy investment in the United States held up through the end of last year, and why it’s kind of a tale of two industries in America right now. The clean electricity sector is booming, while the electric vehicle supply chain is falling apart. So in this episode, it’s all about cars and EVs and how we regulate them in the US, call it our Car Talk episode, and it’s all coming up today on Shift Key.

Robinson Meyer:

[3:38] Ken Gillingham, welcome to Shift Key.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[3:41] Pleasure to speak with you, Robinson.

Robinson Meyer:

[3:43] So the Trump administration comes out with its big greenhouse gas endangerment finding repeal last week. It’s kind of like a two-part document, as we talked about in the past episode. So on the one hand, it’s an argument that the EPA should not regulate greenhouse gases as dangerous pollutants. But then the second part of it is, an argument basically entirely about tailpipe greenhouse gas standards about whether the epa should be regulating greenhouse gases that come out of cars and trucks and the epa argues as you might expect that it shouldn’t i will say that the second Trump administration just like the first Trump administration has to put out a fairly lengthy analysis of why it has reached this conclusion and even though the president during his press briefing announcing this change called global warming, a giant scam. That fact does not feature in their analysis. They take a different approach. They also, as they did in the first Trump administration, actually cite your work all across the analysis. They love to cite your work on the greenhouse gas standards. So can you just give us a sense of like, what did you think about the analysis that you’ve seen from the Trump administration and their legal justification for rolling back the vehicle rules so far.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[4:59] Right. It was a very simplistic analysis in many respects. They simply took the 2024 analysis that was done under the Biden administration, EPA, and they made a set of tweaks. These tweaks happen to have enormous ramifications. The biggest one, of course, is removing the endangerment finding and eliminating greenhouse gases. That is an enormous one. But there are other tweaks that they made. They changed the expected future gasoline price. They changed how they value future fuel savings when people buy a more efficient car.

Robinson Meyer:

[5:39] Can you walk us through a little bit more? So what are the most important of the tweaks that they made? And kind of what message are they trying to send with those tweaks?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[5:49] Well, one message they’re sending is that greenhouse gases don’t matter, other air pollutants don’t matter, and that’s an obvious message. This has been talked about a lot. The other message they’re sending is that consumers, when they’re buying a car, make a decision and fully value the future fuel savings. When you make that assumption, you’re basically saying that consumers fully value the future fuel savings. And because they’re already incorporating the benefit in their decision, they get no benefit from a rule that nudges them into a more efficient car. Those both are pivotal. Either of those two would change the net benefits of the rule. And they’re both huge, many, many millions of dollars, trillions of dollars.

Robinson Meyer:

[6:38] When I started out as an environmental reporter, there was this idea about energy efficiency rules. And I think especially efficiency rules around cars and trucks, which to be clear about what a greenhouse gas standard is when you’re talking about cars and trucks, it really just is a type of energy efficiency rule. And the idea that I heard from researchers, from economists, is that you need some kind of efficiency regulation because this is a market failure, because consumers don’t take into account all the literal monetary benefits they’re going to get from buying a more efficient an appliance or a more efficient car when they make the purchase. It just doesn’t factor into their calculus. And so you need the government to kind of push appliance makers or push car makers toward more efficient products, because otherwise, not only are you going to have consumers maybe not fully maximizing their welfare, so to speak, by buying, you know.

Robinson Meyer:

[7:32] More gas guzzling cars than they should, but also like as a country, you’re going to consume much more gas. And that means that gas prices are going to be higher. And that means even people who make more efficient vehicle purchases are going

Robinson Meyer:

[7:44] to have to pay more for gas, right? It’s this big systematic problem. What I was not aware of is that the economics literature about that finding and that idea has kind of shifted under our feet a few times over the past decade. And that while that might have been the state of the art in 2008, it had kind of changed by the middle of last decade. and now it might have changed again. So can you just update us on like, First of all, was my summary correct? And second, then, like, how did economists change their mind?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[8:24] Yes, your summary is spot on. It’s been long understood that when regular people, anyone goes to a store, consumers go to a store and buy a more efficient appliance or buy a more efficient car, that they appear to value only to some degree the future fuel savings or energy bill savings they would get from the more efficient appliance or more efficient car. This is often called the energy efficiency gap. People have written on it for years. In the car context, there’s a longstanding understanding in the industry, as well as from National Academy’s reports and other sources, that consumers value roughly 2.5 to 3 years, somewhere in that ballpark, of future fuel savings when they purchase a car. Why don’t they value the rest? Well, people usually attribute it to some behavioral feature of the way we make decisions. Which often people use the word inattention. So for example, they might be inattentive to those future fuel savings and really be focusing on just a few attributes of the cars.

Robinson Meyer:

[9:34] We kind of assume that consumers, they buy a new car for a decade or for 12 years. I think the average car on the road now is something like 13 years old. But when they buy the car, as you were saying, they’re only thinking of that first three and a half years. And so all the fuel savings from the back seven or the back nine, just don’t factor into their kind of internal vehicle purchasing function at all.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[9:59] That’s right. And that’s how people had thought about it, that people really paying attention to the first two and a half or three years, and ignoring the remaining nine or so years in that life of the car. And that provides a motivation for policy. If you truly have people who don’t value those future fuel savings, they’re certainly going to value it when they go to the pump and fill up their car with gasoline. There’s no question about that. Everyone agrees that they value it at the time that they’re actually filling up their car with gasoline, but they might not have valued it when they were making that car purchase. That’s kind of fundamentally a strong and longstanding motivation for fuel economy standards. So it may not be surprising that the Trump administration, in trying to rescind the standards, attacked that head on and tried to effectively roll that assumption back as well as rolling back the environmental greenhouse gas engagement finding.

Robinson Meyer:

[10:49] This has changed a little bit. So back maybe around the time of the first Trump administration, the economic literature had shifted somewhat on this question. So, Let’s just roll the clock back to 2015 or 2016. At that point, the Obama era standards had been in effect for some time. Where was the field of economics thinking about the efficiency gains from efficiency-based regulation in cars?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[11:18] That’s a great question. A series of papers came out in the early 2010s, either as working papers initially, and then they were published in those subsequent years. So if you were asking even me around 2015, I would have said, well, it does appear that consumers do value a lot of the future fuel savings and perhaps nearly all of the future fuel savings. If that is the case, that pulls out one of the key motivations for fuel economy standards or vehicle greenhouse gas standards that save fuel. It makes it harder for those standards to look to have positive net benefits.

Robinson Meyer:

[11:52] And I should say that neither the CAFE standards, which are come from the Department of Transportation and regulate fuel mileage, nor the EPA greenhouse gas standards, which regulate the number of the amount of tons of carbon that come out of the car, like the truck tailpipe. They’re not cost free, right? They cost. I mean, at least as of the time of the first Trump administration, they cost like they added to the cost of vehicles by about a thousand dollars or twelve hundred dollars a vehicle on average. Now, consumers saved that over the life of the vehicle many times over. But if consumers are already taking into account those efficiency gains, then that trade-off that the rules kind of forced consumers in maybe weren’t worth it. Before we move on to where we are now, just staying in this 2015 zone …

Robinson Meyer:

[12:39] How did the literature reach this conclusion? What methodology were economists using to say, actually, consumers take all the fuel savings into account when they make a purchasing decision?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[12:49] It’s a great question. So conceptually, they were looking at prices and quantities of vehicles. And they were looking at cases where you had, for some reason, the efficiency was improved. So there was some way, some exogenous way that efficiency was improved. And then looking at how the prices on the market re-equilibrated. And in particular, this was used for used cars. So much of the early 2010 literature that we’re talking about here brings in used cars and new cars. But importantly, it is including used cars and looking at how used car prices change with efficiency changes. Some of the literature was new cars as well, but they were generally finding relatively high valuation ratios.

Robinson Meyer:

[13:34] Give us an example. Is this like consumers, when they were buying a Prius, took into account all the fuel savings from that Prius as compared to like, say, a Toyota Tacoma, like the Prius price included this premium for fuel efficiency?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[13:50] That’s exactly right. Conceptually, you could see it as in the Prius context, the price of the Prius incorporated all of those future fuel savings over the expected life of the vehicle.

Robinson Meyer:

[14:02] That is interesting, because it is true that when you look on Carvana or something, or you look at the cars.com app, two places that I have spent some amount of time in my life, you do see that Prius, used Prius prices are like much higher than sedans of similar size. I mean, it’s a Toyota too, so it gets a kind of premium in the used market anyway. But there is some kind of premium that people assign to cars that get better fuel mileage. So do economists still think this? like do you think the consumers take into account all of those fuel savings when they buy a new car not.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[14:35] All of those fuel savings so I think your questions are a really great one it’s consumers definitely value to some degree future fuel savings. There’s no question about that. Everyone sees it. You can see it in the Prius, although it is a Toyota that does higher retail values, but you can see it across the board. The question is how much of those future fuel savings? You can go back to the original literature that said 2.5 years or three years. That would indicate that there’s a substantial undervaluation of the future fuel savings you could get over the life of the vehicle.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[15:06] More recent evidence has started to come to the conclusion that the previous evidence, that 2.5 or 3 years, was much closer to being correct than the early 2010 articles. And there are two reasons for this. One reason for this is that the newer articles are using updated empirical designs, more careful statistical approaches. I want to emphasize, it’s not easy to estimate this parameter. There are a lot of other variables that influence how people make decisions about cars in terms of all the other attributes of the vehicles, but also the brand, the timing, the gasoline price, all of these things matter.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[15:51] Expectations about gasoline prices matter. This is a very difficult parameter to estimate. So there have been, I would say, improvements in the empirical design of recent studies that I think have helped. That’s the first one. The second reason why we generally are seeing different estimates is that people are being a little bit more careful about whether they take the average of a ratio or the ratio of averages. It’s a subtle point and seems quite minor. Fundamentally, the valuation of those future fuel savings is a ratio. We’re talking about, do they value 50%? Do they value 90%? Do they value 100%? That is a ratio in the sense of the amount that they value over the total amount of future fuel savings.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[16:43] That needs to be handled very carefully in empirical designs. When you correct for that, some of the old studies had to have no problem, but some of them did have some problems. When you correct for that, you actually end up getting similar numbers in some of the previous studies to what we’re finding in the newer studies.

Robinson Meyer:

[17:03] Yeah, basically, we’ve swung all the way back. So literally, there was a mathematical error in some of these studies and how they calculated the percentage of how much people valued the fuel savings. And if you correct for that error, then you swing right back to where the literature used to be.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[17:20] I’m not going to say negative things about my fantastic co-authors and friends, but that’s how science evolves. That’s how we continue learning.

Robinson Meyer:

[17:29] What kind of assumptions did the Trump administration make about fuel prices in its proposal? I mean, does it think that fuel prices are going to get more expensive? Because part of the whole calculus of these rules is that basically, yeah, people like saving fuel when oil is cheap, but they really like saving fuel when oil is expensive. Do they include some predictions about whether gas is going to get more or less expensive in their rulemaking?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[17:56] Well, in the proposed rule for the EPA vehicle greenhouse gas standards, they made one of the assumptions that is one of my favorite assumptions in the entire rule. They arbitrarily said, because there’s an energy dominance agenda, that fuel prices were going to be much, much lower, and thus the benefits from future fuel savings were going to be much, much lower. To their credit, that was entirely unjustified, would never hold up in court, and they removed it in the final rule. In the final rule, they’re using within reason, but very low fuel price, alternative fuel baseline from the Energy Information Administration. And so they still are using a lower number than one might argue, but it’s no longer quite as egregious as it was in the proposed rule.

Robinson Meyer:

[18:40] You had a relatively important paper on the CAFE standards a few years ago at this point and about how the fuel efficiency standards kind of interrelated with the used car market that I continue to think is this really interesting finding that kind of maybe helps people understand why fuel economy is a tough thing to regulate, a very important thing to regulate, but still has these tough follow on effects you might not predict. Can you just describe it to us for a second?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[19:06] So about 10 years ago, Hyundai and Kia stated that their fuel economy was much higher than it actually was. And then suddenly, on one day, they restated their fuel economy. We had transaction price data and we could immediately see how transaction prices for those cars that had their fuel economy restated changed relative to prior, as well as relative to other vehicles in Hyundai and Kia, as well as other similar models by other automakers that did not see this change. In their stated fuel economy.

Robinson Meyer:

[19:38] And what do you find?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[19:40] We found that consumers undervalue fuel economy. It’s actually not too far from the, it’s right in line with the two and a half to three year payback period. So about a 23% or 30% undervaluation. So people value about 23% to 30% of future fuel savings, which means that there’s still 70% to 77% that they don’t value.

Robinson Meyer:

[20:04] There’s a few different things that have happened in the fuel economy rules lately, and I think it’s actually worth putting them all together. So, you know, the US regulates the efficiency of its internal combustion vehicles in two ways. Basically, we had the EPA greenhouse gas standards, those regulated greenhouse gases coming out of tailpipes. But then we also had this much older set of standards from the Department of Transportation called the CAFE standards, which regulate the collective fuel economy of new vehicles. And I think what people may not have realized is that the Trump administration has basically effectively eliminated both of these programs. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act reduced the penalties for the CAFE standard, the Department of Transportation, the older standard to zero. So automakers will not be fined for violating the CAFE standards on the one hand. On the other hand, the EPA is now in the process of trying to repeal not only the greenhouse gas standards for vehicles, but in fact, the idea that it should regulate greenhouse gases altogether. Is there any precedent for the US not having fuel economy or engine efficiency or gas mileage standards of any kind in the historical record? And like, what could we predict will happen from the fact that the US will now no longer have standards of this kind, at least for the next few years?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[21:28] So you’re completely correct that as of now, we effectively do not have standard or as of the finalizing of the CAFE rule, I should really say, because there are two pieces here. Congress and their one big, beautiful bill eliminated the penalties for violating the CAFE standard, which is Corporate Average Fuel Economy standard. In addition, they came out in December with a proposed rule, which made the increase in the standard so minimal that it’s effectively non-binding. So there is actually an increase in the standard. Legally, I think they felt they had to do that. But it’s basically a minimal increase. So there will be non-binding. By non-binding, I just mean they’re ineffective. They’re not doing anything.

Robinson Meyer:

[22:13] And crucially, that really kills the trading market, right? Right. Because the way that EV companies like Tesla, but now like Rivian and Lucid, too, made a good deal of their regulatory income. And for Tesla, some key early profits was by selling credits from their cars, like regulatory credits from their cars to GM, to Nissan, to these producers of these big gas guzzling cars. So they’ve killed a key revenue driver for the all electric automakers as well.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[22:42] That’s right. The proposed rule eliminates something that economists have been pushing for, which is to allow for trading. That came about from Republican economists actually were the ones who made that happen initially. And the trading lowers the costs of compliance. And so they eliminated it, which also is a shot below the bow for all of the EV companies because now they are no longer going to make money from this trading. So it’s an additional hit there. So you’re completely right that with the finalization of the CAFE rule, as expected, in the next few months, we’ll enter a phase with effectively no standards on cars. We have been there in the past. You can go back to before there were standards, before the oil crisis in the 1970s, and cars were very big and very inefficient. Cars are actually bigger today, but they were very inefficient, extremely inefficient. There also are periods, long periods, especially in the 80s, when standards stayed pretty flat. And here I’m talking about corporate average fuel economy standards before 2009, when the EPA vehicle greenhouse gas standard was implemented. So corporate average fuel economy standards, when they were flat, basically we didn’t see much improvement in fuel economy, minimal improvement in fuel economy for years on end.

Robinson Meyer:

[24:02] And did things get worse or they just kind of stayed flat?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[24:05] Stayed flat. They stayed flat. But there was a technology improvement during this time. Just all that technology improvement was poured into increasing horsepower, increasing acceleration, et cetera.

Robinson Meyer:

[24:18] I find this to be one of the most interesting conversations about the whole deal here, because people do look at these standards of the past 10 years and they say, look, cars have gotten bigger during that time. Horsepower has gone up. And because of that, we actually haven’t seen some of the efficiency gains that we once anticipated seeing at the moment the Obama standards were put into place. Basically, like the increasing size of vehicles mostly has kind of eaten into some of those gains. But it seems to me that like we see horsepower improvements and we see vehicles get bigger during periods of time when there are no standards and fuel economy does not improve. And so if we see horsepower improvements and we also see vehicles get bigger and fuel economy does improve, that suggests the fuel economy standards actually did work at least a little bit.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[25:06] It is all about what would have happened otherwise. And I think you’re hitting it on the nose here that we would have seen even potentially larger vehicles and even potentially less efficient vehicles had it not been for the standards. So I think that it’s simply false to say that the standards didn’t do anything because horsepower has gotten larger, because cars have gotten heavier, which is true. Cars have gotten heavier. Horsepower has increased. A lot of it is a switch to SUVs and light trucks and crossovers. That is an ongoing shift. But that would have happened anyway. There are features of the design of standards that may lead to, if you have a lighter standard or more relaxed standard for certain types of vehicles, such as SUVs and light trucks, that provides an incentive to sell SUVs and light trucks. That design feature may have enhanced the upscaling, but the automakers make

Kenneth Gillingham:

[26:03] more money on the big vehicles. They were going to upscale anyway.

Robinson Meyer:

[26:06] Here’s the last question, which is when you look at the assumptions in the rulemaking, when you look at the errors, you know, the agencies have to do this cost benefit analysis when they make a rule change. And without getting too into the weeds, the agency has to prove to the courts, to the American people, that when it changes a regulation, either strengthening a regulation or weakening a regulation is the Trump administration is doing here, that the benefits of that change exceed the costs.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[26:33] Can I just interrupt there? There is a possibility that you can have a net negative benefit policy. You just need to justify it from other legal pathways. Historically, in the courts, it has been very difficult to win a court case when net benefits are negative.

Robinson Meyer:

[26:48] So perfect entree then. When you look at the assumptions made by the Trump administration in their cost benefit analysis, do you believe that if they were updated to reflect more accurate assumptions that the benefits would still exceed the cost of the rule?

Kenneth Gillingham:

[27:03] Oh, far from it. The benefits would be very negative. In fact, even in some of their own scenarios, the net benefits are negative. So it’s pretty clear that the net benefits would not be positive from this rule. I’m sure they know this. The decision to rescind the rules was made before the analysis and the analysis had to follow.

Robinson Meyer:

[27:23] Well, as the legal fight over these rules keeps developing and the economic discussion of the assumptions made in the legal documents. We will keep in touch with you. Ken Gillingham, thank you so much for joining us on Shift Key.

Kenneth Gillingham:

[27:35] It’s a pleasure. Thank you.

Robinson Meyer:

[29:13] And joining us now is Hannah Hess. She’s an associate director at the Rhodium Group. Hannah, welcome to Shift Key.

Hannah Hess:

[29:19] Thank you so much. I’m excited to be here.

Robinson Meyer:

[29:21] So every quarter, the Clean Investment Monitor, which is a project of the Rhodium Group and MIT Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research, has published this summary of all the investment that happened across the clean energy economy over the past quarter, which means that at this point, it’s a pretty good data source and give us a guide to what’s been happening in the clean energy economy since the Inflation Reduction Act era, or at least since the IRA era began. The Q4 2025 report just came out. Can you give us the top line of what it found?

Hannah Hess:

[29:55] Sure. So we’ve been tracking clean investment since about a year after the IRA passed, but our baseline of data goes all the way back to the first quarter of 2018. We find that in Q4, clean investment softened a little bit after a record high Q3 2025 that was largely driven by people purchasing EVs. When we zoom out and look at the full year 2025, we find that it was a record year for clean investment, up 5% from 2024.

Robinson Meyer:

[30:31] So Q3, huge quarter driven by EV purchases, and that’s probably driven especially by the expiring of the IRA demand side tax credits for EV purchasing. Q4, a little soft. One thing I saw in the report was that Q4 2025 is like the first quarter really in the data set that was softer than the quarter a year earlier, right?

Hannah Hess:

[30:56] Yeah. So Q4 is the first instance in our tracking of negative quarter on year growth and clean investment. So since the beginning of this data set, every time we look back at the level observed in the same time period the previous year, it would be an increase even when there was some fluctuation from quarter-on-quarter. And so that would tell us overall this segment is still strong and it’s a good sign that clean investment continues to expand. But that trend ended in Q4 2025 when investment declined 11% from the level that was observed in the last quarter of 2024. New project announcements also softened. So in addition to tracking how much investment is occurring in the construction of new facilities and in those consumer purchases of clean technologies like EVs, heat pumps, rooftop solar, we’re also looking at what developers are doing, how much new projects they’re announcing each quarter. New announced manufacturing projects totaled $3 billion in Q4 2025, which was down 48% both from the previous quarter and year-on-year, and that $3 billion of new manufacturing projects is the lowest quarterly level since Q4 2020.

Hannah Hess:

[32:18] Looking at the full year, announcements for new manufacturing projects were down 26% compared to 2024. So all of these are just signs that the manufacturing segment, which is largely driven by the EV supply chain, is weakening.

Robinson Meyer:

[32:36] I want to talk more about that, but can you zoom out for a second and just tell us what is encompassed by the term clean investment? What sectors are we talking about and what sectors maybe are we not talking about here?

Hannah Hess:

[32:49] So the Clean Investment Monitor tracks investment in three segments of the economy. That’s clean tech manufacturing. So within the EV supply chain, it’s batteries, it’s vehicle assembly, it’s critical minerals processing projects. We also track the manufacturing of solar components, wind components, and electrolyzers for hydrogen. We have a second segment that’s energy and industry, and that lumps together clean electricity, solar, storage, wind, as well as industrial decarbonization projects, which is a much smaller segment. That’s investments in clean products like clean cement and clean steel, as well as sustainable aviation fuels and hydrogen production. And then the final segment of clean investment, we call retail, and that’s small businesses and household purchases of clean technologies that’s, for the most part, EVs and also heat pumps and distributed solar. The thing weaving all of these technologies together is that they were all incentivized by the Inflation Reduction Act. But broadly, we just say investments in the manufacture and deployment of emissions reducing technologies.

Robinson Meyer:

[34:04] What drove the decline in investment last quarter? And a decline not only in real investment, but in investment momentum and the number of announcements people are making. What drove that?

Hannah Hess:

[34:15] So EV purchasing fell off a cliff compared to Q3 2025. And because those retail segment purchases, just like the overall US economy, consumer spending drives most of the clean investment. That was a big dip. But what I view as a more concerning trend is this is the fifth consecutive quarter of decline in clean manufacturing investment. And announcements of new manufacturing projects were exceeded by cancellations of new manufacturing projects. So that’s the pipeline shrinking. And that is concerning for not only what’s happening in Q4, but when we look out for the next couple of years, what is the clean tech manufacturing supply chain look like? What is the U.S. workforce for clean tech manufacturing look like? Lots to unpack there.

Robinson Meyer:

[35:12] The Detroit-based automakers, Ford GM and Stellantis, announced a $50 billion charge combined on their EV investments over the past few months. And we’ve seen a number of them announce that their big flagship projects, like Blue Oval City from Ford in Tennessee, are going to be reoriented from building EVs and batteries to building large internal combustion vehicle trucks. In the data, does it seem like these big by the largest kind of final assembly automakers are driving the bulk of these cancellations? Are you seeing weakness like down further in the supply chain where it’s these individual, you know, parts makers or component makers who make up the actual bulk of the industrial economy who are now experiencing trouble? It’s not just these big, you know, charismatic firms at the top.

Hannah Hess:

[36:13] When I look at all of the cancellations that occurred in cleantech manufacturing in 2025, ranked from the highest value to the lowest value. Top three, General Motors, Stellantis, Ford. But then we see Gotion, FREYR Battery, Core Power, some smaller battery manufacturing projects that while they’re not at the three or four billion level, they really do add up to this record high cancellations that we saw in 2025. I think an important way to contextualize the cancellations also is just to

Hannah Hess:

[36:53] say that when we zoom out, 97% of all the canceled investment in 2025 was in the EV supply chain. That’s a total of $22 billion of canceled projects. And that exceeded the $21 billion of announced projects. So this is really a broader story, I think, than just those big three automakers.

Robinson Meyer:

[37:15] So that’s the bad news. Was there any good news in the data from last quarter?

Hannah Hess:

[37:21] I would love to share a little bit of good news. And that is that clean electricity is holding up better than manufacturing. Solar and storage are really the workhorses when it comes to clean investment. One thing I think is important when you look at this story is to note that the pullback that we’re seeing in clean investment isn’t across the board. Investment in clean electricity was $101 billion over the course of 2025, and that’s up 18% compared to the previous year. We lumped together clean electricity and industrial decarbonization, but clean electricity was 96% of that total. Also, I think it’s important to call out that while we saw $9 billion canceled in the last quarter, that was in a pool of $22 billion worth of new investment announcements. So the pipeline of clean electricity is continuing to grow. And I think that’s a really important story here.

Robinson Meyer:

[38:24] Yeah, it’s so, I mean, this is what we see at Heatmap too. You know, investment in EVs, at least in the near term, has really collapsed. I mean, the EV story is just not what it was a few years ago. But the electricity story is popping off. It is crazy. I mean, it’s all about data centers, right? And it’s all about demand growth. At least that’s what we observed from our end. Maybe you’ve seen something different. but like the solar storage story is just enormous.

Hannah Hess:

[38:49] Truly, yeah. Solar and storage is the leading driver within energy and industry. In just the last quarter, we saw $18 billion worth of utility scale solar and storage installations, which was up about 10% from the same time last year.

Robinson Meyer:

[39:05] Cool. Well, thank you so much for joining us on Shift Key.

Hannah Hess:

[39:10] Thank you, Rob. It’s been really nice to talk.

Robinson Meyer:

[39:14] Shift Key is a production of Heatmap News. Our editors are Jillian Goodman and Nico Lauricella. Multimedia editing and audio engineering is by Jacob Lambert and by Nick Woodbury. Our music is by Adam Kromelow. See you next week.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Boosters say that the energy demand from data centers make VPPs a necessary tool, but big challenges still remain.

The story of electricity in the modern economy is one of large, centralized generation sources — fossil-fuel power plants, solar farms, nuclear reactors, and the like. But devices in our homes, yards, and driveways — from smart thermostats to electric vehicles and air-source heat pumps — can also act as mini-power plants or adjust a home’s energy usage in real time. Link thousands of these resources together to respond to spikes in energy demand or shift electricity load to off-peak hours, and you’ve got what the industry calls a virtual power plant, or VPP.

The theoretical potential of VPPs to maximize the use of existing energy infrastructure — thereby reducing the need to build additional poles, wires, and power plants — has long been recognized. But there are significant coordination challenges between equipment manufacturers, software platforms, and grid operators that have made them both impractical and impracticable. Electricity markets weren’t designed for individual consumers to function as localized power producers. The VPP model also often conflicts with utility incentives that favor infrastructure investments. And some say it would be simpler and more equitable for utilities to build their own battery storage systems to serve the grid directly.

Now, however, many experts say that VPPs’ time to shine is nigh. Homeowners are increasingly pairing rooftop solar with home batteries, installing electric heat pumps, and buying EVs — effectively large batteries on wheels. At the same time, the ongoing data center buildout has pushed electricity demand growth upward for the first time in decades, leaving the industry hungry for new sources of cheap, clean, and quickly deployable power.

“VPPs have been waiting for a crisis and cash to scale and meet the moment. And now we have both,” Mark Dyson, a managing director at RMI, a clean energy think tank, told me. “We have a load growth crisis, and we have a class of customers who have a very high willingness to pay for power as quickly as possible.” Those customers are the data center hyperscalers, of course, who are impatient to circumvent the lengthy grid interconnection queue in any way possible, potentially even by subsidizing VPP programs themselves.

Jigar Shah, former director of the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office under President Biden, is a major VPP booster, calling their scale-up “the fastest and most cost-effective way to support electrification” in a 2024 DOE release announcing a partnership to integrate VPPs onto the electric grid. While VPPs today provide roughly 37.5 gigawatts of flexible capacity, Shah’s goal was to scale that to between 80 and 160 gigawatts by 2030. That’s equivalent to around 7% to 13% of the U.S.’s current utility-scale electricity generating capacity.

Utilities are infamously slow to adopt new technologies. But Apoorv Bhargava, CEO and co-founder of the utility-focused VPP software platform WeaveGrid, told me that he’s “felt a sea change in how aware utilities are that, building my way out is not going to happen; burning my way out is not going to happen.” That’s led, he explained, to an industry-wide recognition that “we need to get much better at flexing resources — whether that’s consumer resources, whether that’s utility-sited resources, whether that’s hyperscalers even. We’ve got to flex.”

Actual VPP capacity appears to have grown more slowly over the past few years than the enthusiasm surrounding the resource’s potential. According to renewable energy consultancy WoodMackenzie, while the number of new VPP programs, offtakers, and company deployments each grew over 33% last year, capacity grew by a more modest 13.7%. Ben Hertz-Shargel, who leads a WoodMac research team focused on distributed energy resources, attributed this slower growth to utility pilot programs that cap VPP participation, rules that limit financial incentives by restricting how VPP capacity is credited, and other market barriers that make it difficult for customers to engage.

Dyson similarly said he sees “friction on the utility side, on the regulatory side, to align the incentive programs with real needs.” These points of friction include requirements for all participating devices to communicate real-time performance data — even for minor, easily modeled metrics such as a smart thermostat’s output — as well as utilities’ hesitancy to share household-level metering data with third parties, even when it’s necessary to enroll in a VPP program. Figuring out new norms for utilities and state regulations is “the nut that we have to crack,” he said.

One of the more befuddling aspects of the whole VPP ecosystem, however, can be just trying to parse out what services a VPP program can actually provide. The term VPP can refer to anything from decades-old demand response programs that have customers manually shutting off appliances during periods of grid stress to aspirational, fully integrated systems that continually and automatically respond to the grid’s needs.

“When a customer like a utility says, I want to do a VPP, nobody knows what they’re talking about. And when a regulator says we should enable VPPs, nobody knows what services they’re selling,” Bhargava told me.

In an effort to help clarify things, the software company EnergyHub developed what it calls the VPP Maturity Model, which defines five levels of maturity. Level 0 represents basic demand response. A utility might call up an industrial customer and tell them to reduce their load, or use price signals to encourage households to cut down on electricity use in the evening. Level 1 incorporates smart devices that can send data back to the utility, while at Level 2, VPPs can more precisely ramp load up or down over a period of hours with better monitoring, forecasting, and some partial autonomy — this is where most advanced VPPs are at today.

Moving into Levels 3 and 4 involves more automation, the ability to handle extended grid events, and ultimately full integration with the utility and grid-operator’s systems to provide 24/7 value. The ultimate goal, according to EnergyHub’s model, is for VPPs to operate indistinguishably from conventional power plants, eventually surpassing them in capabilities.

But some question whether imitating such a fundamentally different resource should actually be the end game.

“What we don’t need is a bunch of virtual power plants that are overconstrained to act just like gas plants,” Dyson told me. By trying to engineer “a new technology to behave like an old technology,” he said, grid operators risk overlooking the unique value VPPs can provide — particularly on the distribution grid, which delivers electricity directly to homes and businesses. Here, VPPs can help manage voltage regulation or work to avoid overloads on lines with many distributed resources, such as solar panels — things traditional power plants can’t do because they’re not connected to these local lines.

Still others are frankly dubious of the value of large-scale VPP programs in the first place. “The benefits of virtual power plants, they look really tantalizing on paper,” Ryan Hanna, a research scientist at UC San Diego’s Center for Energy Research told me. “Ultimately, they’re providing electric services to the electric power grid that the power grid needs. But other resources could equally provide those.”

Why not, he posited, just incentivize or require utilities to incorporate battery storage systems at either the transmission or distribution levels into their long-term plans for meeting demand? Large-scale batteries would also help utilities maximize the value of their existing assets and capture many of the other benefits VPPs promise. Plus, they would do it at a “larger size, and therefore a lower unit cost,” Hanna told me.

Many VPP companies would certainly dispute the cost argument, and also note that with grid interconnection queues stretching on for years, VPPs offer a way to deploy aggregated resources far more quickly than building out and connecting new, centralized assets.

But another advantage of Hanna’s utility-led approach, he said, is that the benefits would be shared equally — all customers would see similar savings on their electricity bills as grid-scale batteries mitigate the need for expensive new infrastructure, the cost of which is typically passed on to ratepayers. VPPs, on the other hand, deliver an outsize benefit to the customers incentivized to participate by dint of their neighborhood’s specific needs, and with the cash on hand to invest in resources such as a home battery or an EV.

This echoes a familiar equity argument made about rooftop solar: that the financial benefits accrue only to households that can afford the upfront investment, while the cost of maintaining shared grid infrastructure falls more heavily on non-participants. Except in the case of VPPs, non-participants also stand to benefit — just less — if the programs succeed in driving down system costs and improving grid reliability.

“I may pay Customer A and Customer B may sit on the sidelines,” Matthew Plante, co-founder and president of the VPP operator Voltus, told me. “Customer A gets a direct payment, but customer B’s rates go down. And so everyone benefits, even if not directly.” On the flip side, if the VPP didn’t exist, that would be a lose-lose for all customers.

Plante is certainly not opposed to the idea of utilities building grid-scale batteries themselves, though. Neither he nor anyone else can afford to be picky about the way new capacity comes online right now, he said. “I think we all want to say, what is quickest and most efficient and most economical? And let’s choose that solution. Sometimes it’s got to be both.”

For its part, Voltus is betting that its pathway to scale runs through its recently announced partnership with the U.S. division of Octopus Energy, the U.K.’s largest energy supplier, which provides software to utilities to coordinate distributed energy resources and enroll customers in VPP programs. Together, they plan to build portfolios of flexible capacity for utilities and wholesale electricity markets, areas where Octopus has extensive experience. “So that gives us market access in a much quicker way,” Plante told me.”

At this moment, there’s no customer more motivated than a data center to bring large volumes of clean energy online as quickly as possible, in whatever way possible. Because while data enters themselves can theoretically act as flexible loads, ramping up and down in response to grid conditions, operators would probably rather pay others to be flexible instead.

“Does a data center company ever want to say, okay, I won’t run my training model for a couple hours on the hottest day of the year? They don’t, because it’s worth a lot of money to run that training model 24/7,” Dyson told me. “Instead, the opportunity here is to use the money that generates to pay other people to flex their load, or pay other people to adopt batteries or other resources that can help create headroom on the system.”

Both Plante of Voltus and Bhargava of WeaveGrid confirmed that hyperscalers are excited by the idea of subsidizing VPP programs in one form or another. That could look like providing capital to help customers in a data center’s service territory buy residential batteries or contracts that guarantee a return for VPP aggregators like Voltus. “I think they recognize in us an ability to get capacity unlocked quickly,” Plante told me.

Yet another knot in this whole equation, however, is that even given hyperscalers’ enthusiasm and the maturation of VPP technology, most utilities still lack a natural incentive to support this resource. That’s because investor-owned utilities — which serve approximately 70% of U.S. electricity customers — earn profits primarily by building infrastructure such as power plants and transmission lines, receiving a guaranteed rate of return on that capital investment. Successful VPPs, on the other hand, reduce a utility’s need to build new assets.

The industry is well aware of this fundamental disconnect, though some contend that current load growth ought to quell this concern. Utilities will still need to build significant new infrastructure to meet the moment, Bhargava told me, and are now under intense pressure to expand the grid’s capacity in other ways, as well.

“They cannot build fast enough. There’s not enough copper, there’s not enough transformers, there’s not enough people,” Bhargava explained. VPPs, he expects, will allow utilities to better prioritize infrastructure upgrades that stand to be most impactful, such as building a substation near a data center instead of in a suburb that could be adequately served by distributed resources.

The real question he sees now is, “How do we make our flexibility as good as copper? How do we make people trust in it as much as they would trust in upgrading the system?”

On the real copper gap, Illinois’ atomic mojo, and offshore headwinds

Current conditions: The deadliest avalanche in modern California history killed at least eight skiers near Lake Tahoe • Strong winds are raising the wildfire risk across vast swaths of the northern Plains, from Montana to the Dakotas, and the Southwest, especially New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma • Nairobi is bracing for days more of rain as the Kenyan capital battles severe flooding.

Last week, the Environmental Protection Agency repealed the “endangerment finding” that undergirds all federal greenhouse gas regulations, effectively eliminating the justification for curbs on carbon dioxide from tailpipes or smokestacks. That was great news for the nation’s shrinking fleet of coal-fired power plants. Now there’s even more help on the way from the Trump administration. The agency plans to curb rules on how much hazard pollutants, including mercury, coal plants are allowed to emit, The New York Times reported Wednesday, citing leaked internal documents. Senior EPA officials are reportedly expected to announce the regulatory change during a trip to Louisville, Kentucky on Friday. While coal plant owners will no doubt welcome less restrictive regulations, the effort may not do much to keep some of the nation’s dirtiest stations running. Despite the Trump administration’s orders to keep coal generators open past retirement, as Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote in November, the plants keep breaking down.

At the same time, the blowback to the so-called climate killshot the EPA took by rescinding the endangerment finding has just begun. Environmental groups just filed a lawsuit challenging the agency’s interpretation of the Clean Air Act to cover only the effects of regional pollution, not global emissions, according to Landmark, a newsletter tracking climate litigation.

Copper prices — as readers of this newsletter are surely well aware — are booming as demand for the metal needed for virtually every electrical application skyrockets. Just last month, Amazon inked a deal with Rio Tinto to buy America’s first new copper output for its data center buildout. But new research from a leading mineral supply chain analyst suggests the U.S. can meet 145% of its annual demand using raw copper from overseas and domestic mines and from scrap. By contrast, China — the world’s largest consumer — can source just 40% of its copper that way. What the U.S. lacks, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, is the downstream processing capacity to turn raw copper into the copper cathode manufacturers need. “The U.S. is producing more copper than it uses, and is far more self-reliant than China in terms of raw materials,” Benchmark analyst Albert Mackenzie told the Financial Times. The research calls into question the Trump administration’s mineral policy, which includes stockpiling copper from jointly-owned ventures in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and domestically. “Stockpiling metal ores doesn’t help if you don’t have midstream processing,” Stephen Empedocles, chief executive of US lobbying firm Clark Street Associates, told the newspaper.

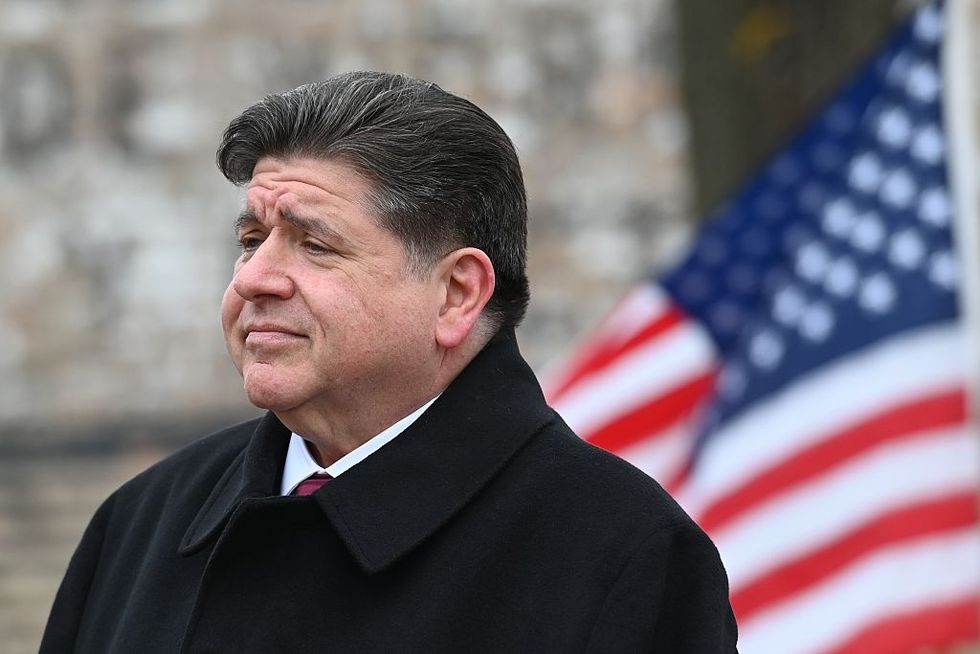

Illinois generates more of its power from nuclear energy than any other state. Yet for years the state has banned construction of new reactors. Governor JB Pritzker, a Democrat, partially lifted the prohibition in 2023, allowing for development of as-yet-nonexistent small modular reactors. With excitement about deploying large reactors with time-tested designs now building, Pritzker last month signed legislation fully repealing the ban. In his state of the state address on Wednesday, the governor listed the expansion of atomic energy among his administration’s top priorities. “Illinois is already No. 1 in clean nuclear energy production,” he said. “That is a leadership mantle that we must hold onto.” Shortly afterward, he issued an executive order directing state agencies to help speed up siting and construction of new reactors. Asked what he thought of the governor’s move, Emmet Penney, a native Chicagoan and nuclear expert at the right-leaning Foundation for American Innovation, told me the state’s nuclear lead is “an advantage that Pritzker wisely wants to maintain.” He pointed out that the policy change seems to be copying New York Governor Kathy Hochul’s playbook. “The governor’s nuclear leadership in the Land of Lincoln — first repealing the moratorium and now this Hochul-inspired executive order — signal that the nuclear renaissance is a new bipartisan commitment.”

The U.S. is even taking an interest in building nuclear reactors in the nation that, until 1946, was the nascent American empire’s largest overseas territory. The Philippines built an American-made nuclear reactor in the 1980s, but abandoned the single-reactor project on the Bataan peninsula after the Chernobyl accident and the fall of the Ferdinand Marcos dictatorship that considered the plant a key state project. For years now, there’s been a growing push in Manila to meet the country’s soaring electricity needs by restarting work on the plant or building new reactors. But Washington has largely ignored those efforts, even as the Russians, Canadians, and Koreans eyed taking on the project. Now the Trump administration is lending its hand for deploying small modular reactors. The U.S. Trade and Development Agency just announced funding to help the utility MGEN conduct a technical review of U.S. SMR designs, NucNet reported Wednesday.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Despite the American government’s crusade against the sector, Europe is going all in on offshore wind. For a glimpse of what an industry not thrust into legal turmoil by the federal government looks like, consider that just on Wednesday the homepage of the trade publication OffshoreWIND.biz featured stories about major advancements on at least three projects totaling nearly 5 gigawatts:

That’s not to say everything is — forgive me — breezy for the industry. Germany currently gives renewables priority when connecting to the grid, but a new draft law would give grid operators more discretion when it comes to offshore wind, according to a leaked document seen by Windpower Monthly.

American clean energy manufacturing is in retreat as the Trump administration’s attacks on consumer incentives have forced companies to reorient their strategies. But there is at least one company setting up its factories in the U.S. The sodium-ion battery startup Syntropic Power announced plans to build 2 gigawatts of storage projects in 2026. While the North Carolina-based company “does not reveal where it manufactures its battery systems,” Solar Power World reported, it “does say” it’s establishing manufacturing capacity in the U.S. “We’re making this move now because the U.S. market needs storage that can be deployed with confidence, supported by certification, insurance acceptance, and a secure domestic supply chain,” said Phillip Martin, Syntropic’s chief executive.

For years now, U.S. manufacturers have touted sodium-ion batteries as the next big thing, given that the minerals needed to store energy are more abundant and don’t afford China the same supply-chain advantage that lithium-ion packs do. But as my colleague Katie Brigham covered last April, it’s been difficult building a business around dethroning lithium. New entrants are trying proprietary chemistries to avoid the mistakes other companies made, as Katie wrote in October when the startup Alsym launched a new stationary battery product.

Last spring, Heron Power, the next-generation transformer manufacturer led by a former Tesla executive, raised $38 million in a Series A round. Weeks later, Spain’s entire grid collapsed from voltage fluctuations spurred by a shortage of thermal power and not enough inverters to handle the country’s vast output of solar power — the exact kind of problem Heron Power’s equipment is meant to solve. That real-life evidence, coupled with the general boom in electrical equipment, has clearly helped the sales pitch. On Wednesday, the company closed a $140 million Series B round co-led by the venture giants Andreessen Horowitz and Breakthrough Energy Ventures. “We need new, more capable solutions to keep pace with accelerating energy demand and the rapid growth of gigascale compute,” Drew Baglino, Heron’s founder and chief executive, said in a statement. “Too much of today’s electrical infrastructure is passive, clunky equipment designed decades ago. At Heron we are manifesting an alternative future, where modern power electronics enable projects to come online faster, the grid to operate more reliably, and scale affordably.”

A senior scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy on what Trump has lost by dismantling Biden’s energy resilience strategy.

A fossil fuel superpower cannot sustain deep emissions reductions if doing so drives up costs for vulnerable consumers, undercuts strategic domestic industries, or threatens the survival of communities that depend on fossil fuel production. That makes America’s climate problem an economic problem.

Or at least that was the theory behind Biden-era climate policy. The agenda embedded in major legislation — including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act — combined direct emissions-reduction tools like clean energy tax credits with a broader set of policies aimed at reshaping the U.S. economy to support long-term decarbonization. At a minimum, this mix of emissions-reducing and transformation-inducing policies promised a valuable test of political economy: whether sustained investments in both clean energy industries and in the most vulnerable households and communities could help build the economic and institutional foundations for a faster and less disruptive energy transition.

Sweeping policy reversals have cut these efforts short. Abandoning the strategy makes the U.S. economy less resilient to the decline of fossil fuels. It also risks sowing distrust among communities and firms that were poised to benefit, complicating future efforts to recommit to the economic policies needed to sustain an energy transition.

This agenda rested on the idea that sustaining decarbonization would require structural changes across the economy, not just cleaner sources of energy. First, in a country that derives substantial economic and geopolitical power from carbon-intensive industries, a durable energy transition would require the United States to become a clean energy superpower in its own right. Only then could the domestic economy plausibly gain, rather than lose, from a shift away from fossil fuels.

Second, with millions of households struggling to afford basic energy services and fossil fuels often providing relatively cheap energy, climate policy would need to ensure that clean energy deployment reduces household energy burdens rather than exacerbates them.

Third, policies would need to strengthen the economic resilience of communities that rely heavily on fossil fuel industries so the energy transition does not translate into shrinking tax bases, school closures, and lost economic opportunity in places that have powered the country for generations.

This strategy to reshape the economy for the energy transition has largely been dismantled under President Trump.

My recent research examines federal support for fossil fuel-reliant communities, assessing President Biden’s stated goal of “revitalizing the economies of coal, oil, gas, and power plant communities.” Federal spending data provides little evidence that these at-risk communities have been effectively targeted. One reason is timing: While legislation authorized unprecedented support, actual disbursements lagged far behind those commitments.

Many of the key policies — including $4 billion in manufacturing tax credits reserved for communities affected by coal closures — took years to move from statutory language to implementation guidance and final project selection. As a result, aside from certain pandemic-era programs, fossil fuel-reliant communities had received limited support by the time Trump took office last year.

Since then, the Trump administration and Congress have canceled projects intended to benefit fossil fuel-reliant regions, including carbon capture and clean hydrogen demonstrations, and discontinued programs designed to help communities access and implement federal funding.

Other elements of the strategy to reduce the country’s vulnerability to fossil fuel decline have fared even worse under the Trump administration. Programs intended to help households access and afford clean energy — most notably the $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund — were effectively canceled last year, including attempts to claw back previously awarded funds. More broadly, the rollback of IRA programs with an explicit equity or justice focus leaves lower-income households more exposed to the economic disruptions that can accompany an energy transition.

By contrast, subsidies and grant programs aimed at strengthening the country’s energy manufacturing base have largely survived, including tax credits supporting domestic production of batteries, solar components, and other key technologies. Even so, the investment environment has weakened. Automakers have scaled back planned U.S. battery manufacturing expansions. Clean Investment Monitor data shows annual clean energy manufacturing investments on pace to decline in 2025, after rising sharply from 2022 to 2024. Whatever one believed about the potential to build globally competitive domestic supply chains for the technologies that will power clean energy systems, those prospects have dimmed amid slowing investment and the Trump administration’s prioritization of fossil fuels.

Perhaps these outcomes were unavoidable. Building a strong domestic solar industry was always uncertain, and place-based economic development programs have a mixed track record even under favorable conditions. Still, the Biden-era approach reflected a coherent theory of climate politics that warranted a real-world test.

Over the past year, debates in climate policy circles have centered on whether clean energy progress can continue under less supportive federal policies, with plausible cases made on both sides. The fate of Biden’s broader economic strategy to sustain the energy transition, however, is less ambiguous. The underlying dependence of the United States on fossil fuels across industries, households, and many local communities remains largely unchanged.