You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

If he loses — which, at this stage, seems likely — this will all have been for nought.

Let’s start here: Joe Biden is losing the presidential election. He is now roughly 2 points behind Donald Trump in national polls, according to the FiveThirtyEight average. Though that may sound small, no Democrat has been further behind in the polls, at this point in the election, since Al Gore in 2000.

Some of this collapse is due to fatigue with Democrats in general, part of a global wave of anti-incumbent fervor. But at least some is specific to Biden. In some swing state polls, a large gap has opened up between Biden and the Democratic Senate candidate. Senator Tammy Baldwin, for instance, is running 12 points ahead of Biden in Wisconsin, according to an AARP poll released on Tuesday. Wisconsin is one of three key states that the president must win to clinch re-election.

This is, obviously, a significant problem for Democrats. Senator Michael Bennett, a Democrat of Colorado, believes the party is on track to lose control of the House and Senate in addition to the presidency.

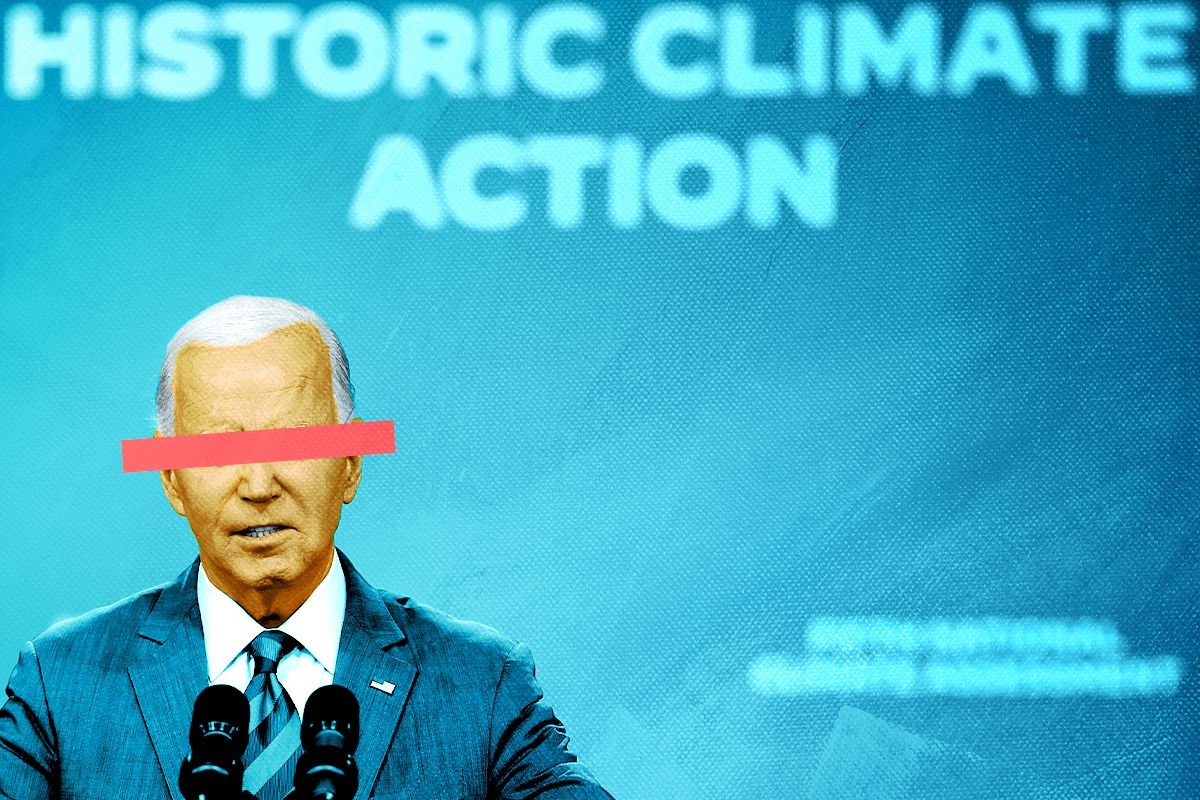

But it is a particular issue for those who believe the American economy should decarbonize. Biden alone among candidates in the presidential election has an impressive climate record: He fought for the passage of — and subsequently signed — the Inflation Reduction Act, the largest climate law in American history. For 30 years, Democrats had tried and failed to pass comprehensive climate legislation through the U.S. Senate; it finally happened under Biden’s watch.

The Biden administration has also used its considerable presidential powers to lower carbon emissions: The Environmental Protection Agency has proposed rules that would significantly cut heat-trapping pollution from power plants, cars and trucks, and the oil and gas sector, and the Department of Energy and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration have each set out their own emissions-reducing rules.

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law is also helping to establish new, multi-billion-dollar “hubs” that aim to commercialize clean hydrogen production and carbon removal technologies. The president even stepped in to block new natural gas export terminals — a move that I have more complicated feelings about, but that, in any case, a federal judge has now blocked.

I don’t need to go over the litany of Trump’s environmental misdeeds, but suffice it to say that during his time in office, Donald Trump demonstrated a distinct glee in tearing up climate regulations and blocking decarbonization. He withdrew America from the Paris Agreement, rolled back the EPA’s climate rules, and deemed climate change a “hoax.” In his second term, he again seeks to overturn the EPA’s new climate proposals, including requirements that automakers sell more electric vehicles. The Heritage Foundation’s more complete plans for a second Trump administration — dubbed Project 2025 — calls for closing dozens of government offices concerned with climate change, ending energy efficiency standards, repealing the IRA’s tax credits, and breaking up the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Suffice it to say: Biden is the only serious candidate in the race who wants to do something about climate change. He is the climate candidate, and he has a climate record to run on. But Biden has miserably failed to communicate any of these policy successes to the masses. Nearly 60% of voters said they knew little or nothing about the Inflation Reduction Act, according to the Heatmap Climate Poll, conducted late last year. (A Yale and George Mason University survey found roughly similar results.)

You might think that reveals a canny strategy on the White House’s part: Perhaps it knows the IRA is divisive, and so it is only bragging about the law to the right audience. But polling shows Biden’s policies are consistently failing to reach the very Americans who should have heard about them — the subset of Americans who are worried about climate change and want to see something done about it. Of Americans who believe climate change is a “very important” issue, only 10% have heard or read a lot about Biden’s climate policies, according to an April CBS News/YouGov poll. And nearly half of Americans who rate climate change highly said that they have heard nothing or “very little” about Biden’s efforts, according to the same survey.

That is not the only poll to reach that conclusion. Another recent survey, conducted by the Associated Press and the NORC Center for Public Research, found that nearly half of Americans were more concerned about climate change this year than they were last year — but that barely any of that cohort had heard about the IRA, and few thought the legislation would affect their lives or mitigate climate change. Nearly half of the poll’s respondents either didn’t know whether the IRA would help climate change or thought it would make it worse. The IRA — and Biden’s climate agenda more broadly — is failing to break through.

Now, I don’t labor under the impression that climate change is a particularly potent or popular electoral issue. I’ve come to think that climate, if not actively deleterious to Democrats, is at least an electoral sideshow to the more enduring issues at the center of American politics: the economy, interest rates, taxes, health care, and national security. (Of course, climate change could vastly reshape the American economy and the public’s health, but other, more immediate concerns — such as employment, inflation, or abortion access — understandably remain more front-of-mind for voters.)

But as a climate journalist, I’ve still found the past two years perplexing. Why do so few people seem to understand the IRA’s goals? Why has the Biden administration struggled so much to communicate the IRA’s most popular aspect — namely, that it will reduce electricity costs (if not inflation itself) for voters? Consider the bare political record here: The Biden administration passed a law called the Inflation Reduction Act, and inflation subsequently came down. A more competent administration would be all over that simplistic, but still potent, victory. So why don’t more people seem to know about what Biden is doing? How is the federal government doing so much on climate change and nobody — not even climate-concerned Democrats — seem to care?

These questions have an easy answer: The candidate is not capable of communicating these victories, so they are not breaking through. Biden, in his diminished state, is not a skilled, crisp, or even very decipherable communicator. As Ezra Klein has observed, Biden is not generating the kind of memorable moments or sterling speeches that Democrats can share among themselves. He is barely speaking in complete sentences. In today’s fragmented media landscape, where first-person accounts and viral videos can go much further than news stories or wonky analysis, the candidate must be the chief champion of his or her victories. Judging from Biden’s disastrous performance at the first presidential debate — and his relative lack of lengthy, unscripted public appearances since then, and the account of those who have interacted with him — he seemingly cannot meet that standard.

Biden’s tremendous climate legacy rests on whether he can sell his accomplishments to the public and win the 2024 election. And that ability is faltering, to say the least.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

In this emergency episode, Rob unpacks the decision with international supply chain specialist Jonas Nahm.

The Supreme Court just struck down President Trump’s most ambitious tariff plan. What does that ruling mean for clean energy? For the data center boom? For America’s industrial policy?

On this emergency episode of Shift Key, Rob is joined by Jonas Nahm, a professor of economic and industrial policy at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, D.C. They discuss the ruling, the other authorities that Trump could now use to raise trade levies, and what (if anything) the change could mean for electric vehicles, solar panels, and more.

Shift Key is hosted by Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Here is an excerpt from their conversation:

Robinson Meyer: One thing I’m hearing in this list is that there’s five other tariff authorities he could use, and while some of them have restrictions on time or duration or tariff rate, there’s actually still a good amount of like untested tariff authority out there in the law. And if the president and his administration were quite devoted, they would be able to go out there and figure out the limits of 338, or figure out the limits of of 301?

Jonas Nahm: Yeah, I mean, I think one thing to also think about is, what is the purpose of these tariffs, right? And so I think the justifications from the administration have been varied and changed over time. But, you know, they’ve taken in a significant amount of revenue, some $30 billion a month from these tariffs. This was about four times as much as in the Biden administration. And so there is some money coming in from this. And so 122, the 10% immediately would bring back some of that revenue that is otherwise lost. One question is what’s going to happen to refunds from the IEEPA tariffs? Are they going to have to pay this back? It seems like that’s also kind of a court battle that needs to be fought out. And the Supreme Court didn’t weigh in on that. But, you know, the estimates show that if you brought the 122 in at 10%, you would actually recoup a lot of the money that you would otherwise lose and the effective tariff rate in the U.S. Would go back from 10% to about 15%, roughly to where it was before the Supreme Court ruled on it.

Meyer: Has the effect of tariffs from the Trump administration been larger or smaller than what you thought it would be? Not necessarily in the immediate aftermath of “liberation day” because he announced these giant tariffs and then kind of walked some of them back. But the tariff rate has gone up a lot in the past year. Has the effect of that on the economy been more or less than you expected?

Nahm: I think that the industrial policy justification that they have also used is a completely different bucket, right? So you can use this for revenue, and then you can just sort of tax different sectors at different times as long as the sum overall is what you want it to be. From an industrial policy perspective, all of this uncertainty is not very helpful because if you’re thinking about companies making major investment decisions and you have this IEEPA Supreme Court case sort of hanging over the situation for the past year, now we don’t know exactly what they’re going to replace it with, but you’re making a $10 billion decision to build a new manufacturing plant. You may want to sit that out until you know what exactly the environment is and also what the environment is for the components that you need to import, right? So a lot of U.S. imports actually go into domestic manufacturing. And so it’s not just the product that we’re trying to kind of compete with by making it domestically, but also the inputs that we need to make that product here that are being affected.

And so for those kinds of supply chain rewiring industrial policy decisions, you probably want a lot more certainty than we’ve had. And so the Supreme Court ruling against the IEEPA tariff justification is certainly more certainty in all of this. So we’ve now taken that off the list. But we are not clear what the new environment will look like and how long it’s going to stick around. And so from sort of an industrial policy perspective, that’s not really what you want. Ideally, what you would have is very predictable tariffs that give companies time to become competitive without the competition from abroad, and then also a very credible commitment to taking these tariffs away at some point so that the companies have an incentive to become competitive behind the tariff wall and then compete on their own. That’s sort of the ideal case. And we’re somewhat far from the ideal case. Given the uncertainty, given the lack of clarity on whether these things are going to stick around or not, or might be extended forever, and sort of the politics in the U.S. that make it much harder to take tariffs away than to impose them.

You can find a full transcript of the episode here.

Mentioned:

From Heatmap: Clean Energy Looks to (Mostly) Come Out Ahead After the Supreme Court’s Tariff Ruling

This episode of Shift Key is sponsored by ...

Accelerate your clean energy career with Yale’s online certificate programs. Explore the 10-month Financing and Deploying Clean Energy program or the 5-month Clean and Equitable Energy Development program. Use referral code HeatMap26 and get your application in by the priority deadline for $500 off tuition to one of Yale’s online certificate programs in clean energy. Learn more at cbey.yale.edu/online-learning-opportunities.

Music for Shift Key is by Adam Kromelow.

This transcript has been automatically generated.

Subscribe to “Shift Key” and find this episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon, or wherever you get your podcasts.

You can also add the show’s RSS feed to your podcast app to follow us directly.

Robinson Meyer:

[1:25] Hi, I’m Robinson Meyer, the founding executive editor of Heatmap News. It is Friday, February 20. This morning, the Supreme Court threw out President Trump’s most aggressive tariffs, ruling that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977, usually called IEEPA, does not allow the president to impose broad, indiscriminate tariffs on other countries. Had Congress intended to convey the distinct and extraordinary power to impose tariffs, it would have done so expressly, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote. It was a bit of a stitched together decision. Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Brett Kavanaugh dissented, while Neil Gorsuch, Amy Coney Barrett, and the chief justice ruled with the liberals, although the liberals only concurred with some of the decision. But it takes away a major tool of economic and diplomatic policy making for President Trump.

Robinson Meyer:

[2:12] There were really two sets of tariffs affected by this decision. One was a set of so-called reciprocal tariffs imposed on most countries in the world and set between 10% and 50%. And the second were what Trump called the fentanyl tariffs on China, Mexico, and Canada. Now, the president basically immediately followed up this ruling by saying he would impose a 10% universal tariff on all countries. We’re still trying to understand how exactly he would do that and what it would mean, and we’ll talk about it on the show. But we wanted to have a conversation on an emergency basis here on an emergency shift key episode about what this means for clean energy and what this could also mean for Trump’s industrial policy, such as it is going forward.

Robinson Meyer:

[2:53] Joining us today is Jonas Nahm. He’s an associate professor at the John Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, D.C., and he was recently senior economist for industrial strategy at the White House Council of Economic Advisors. He studies industrial policy, supply chains and trade, and he’s the author of Collaborative Advantage: Forging Green Industries in the New Global Economy. Jonas, welcome to Shift Key.

Jonas Nahm:

[3:18] Thank you for having me. I’m finally on.

Robinson Meyer:

[3:20] You’re finally here. We finally got you. So I think let’s just start here. What do you make of the ruling today and then the president’s kind of successive 10% tariff announcement?

Jonas Nahm:

[3:33] I don’t think this was surprising, right? We had, during the hearings, kind of gotten this impression that the judges were somewhat skeptical, at least, of the ability of the president to use IEEPA to justify these tariffs. And so I think the surprise was really that it took so long. There were lots of rumors floating around for the past couple of months that this would come out any time. And so it finally came, but it sort of came in the form that everyone expected. And the conclusion today was that this is not a tariff statute and that there are other authorities for the president to use to do these things, but this isn’t one of them.

Robinson Meyer:

[4:09] I feel like the most interesting thing, I kind of hinted at this in the intro, was that Brett Kavanaugh, ruled, first of all, that the tariffs were legal, which is kind of crazy, but also that he was like, this is not the proper use of the major questions doctrine, a doctrine he invented to constrain executive authority. But that’s neither here nor there.

Jonas Nahm:

[4:28] Which the liberal justices also didn’t sign on to, right? So it was sort of three people saying this is major questions, and then three people saying this is just, you know, illegal.

Robinson Meyer:

[4:39] Yes. And I think maybe crucially for this audience, Justice Gorsuch cited disapprovingly the Trump administration’s argument that a future president could use IEEPA, the statute in question here, to impose tariffs on fossil fuels or internal combustion engines because it considers climate change to be a national security threat. That was like an argument made by President Trump’s team on behalf of the tariffs to convey their belief that IEEPA had this huge economic policymaking power within it. And Justice Gorsuch was like, no, no, no, it doesn’t let you do that. And it also doesn’t let you impose these tariffs on all these other countries. OK, so I will say I have basically spent every moment up until now not learning about the other tariff authorities. They all are like known by a different number. And it always seemed like people were mentioning a new one. So can you walk us through just like with IEEPA out of the way, what are the other things? Authorities or powers under the law that have been used to impose tariffs on the past or that are seen as kind of being the other powers the president could invoke here if he wanted to keep slapping tariffs on major trading partners?

Jonas Nahm:

[6:00] So one of the big advantages of the IEEPA path for the administration was that it didn’t really involve a lot of procedure. And they had a lot of discretion. Now, no more. But at the time, thinking that they could do this, they had a lot of discretion about how to do this, who to apply this to, which products to exempt, and how to change it very quickly. And so it was basically fairly unconstrained. And so the other authorities all come with more process. And many of them are already in place with more process. So I think one thing to maybe start with is that the IEEPA tariffs are only one part of this tariff stack, and that different products have other tariffs applied to them already. Some of them stack on top of one another, some of them don’t, but there are many kind of authorities in this space that are being used at the same time.

Jonas Nahm:

[6:51] The president came out today and said they’re going to impose 10% universal tariffs under the Section 122, which is from the Trade Act of 1974, which is really to address kind of a large and serious deficit, it can be done very immediately, but it’s capped at 15%. They said they’re going to use 10. The problem for them is that it expires in 150 days unless Congress extends it. So it can sort of stop the revenue loss from taking away the reciprocal and the fentanyl tariffs. It can buy time for permanent fixes, but itself is not really a permanent solution unless there’s congressional buy-in in 150 days, which seems somewhat unlikely. So that’s what they’ve already decided they’re going to use sort of as the bridge to get to these other authorities.

Jonas Nahm:

[7:40] There’s another tariff authority called Section 232, which is about national security related issues. And so there you need to have an investigation and then you can impose these tariffs. We have lots of these investigations ongoing. Some of them are already completed, but pharmaceuticals, robotics, chips, I mean, there’s a bunch of them that are out there. And so what they don’t like about this is that you have to have this investigation so it’s not immediate. it. And so it requires a little bit of process.

Robinson Meyer:

[8:11] Like a Commerce Department investigation, right? This is like a, it’s like a known process where they...

Jonas Nahm:

[8:18] Yeah, and there needs to be a hearing and yes, all of those things. So that’s 232. And then you have Section 301, which is about unfair trade practices. That also requires an investigation and a public hearing, kind of a common period where industry can weigh in. And so you could use that to recreate these tariffs on a country by country basis, the Section 232 tears are mostly at the sectoral level. So the investigations are about sectors that have national security implications, although that has also been stretched widely by this administration. We’ve applied them to kitchen cabinets in this past year, so I don’t immediately follow the national security implications there. But, you know, there is some leeway there in how this is laid out. Section 301 is about unfair trade practices. And then there are the tariffs that were used, you know, almost 100 years ago after the depression, which is Section 338. That gets thrown around a lot. I think it has a lot less procedural constraints attached to it than these other ones. But it’s also untested in modern courts. And this would require the administration to prove that there’s discrimination against U.S. exports. And you could imagine a lot of litigation around how to define discrimination. And so these are sort of the broad authorities that exist and that the administration

Jonas Nahm:

[9:38] has signaled they will rely on. I think mostly the first three.

Robinson Meyer:

[9:41] It does seem like, I think one thing hearing this list is that there’s five other tariff authorities he could use. And while some of them have restrictions on time or duration or tariff rate, there’s actually still a good amount of like untested tariff authority out there in the law and if the president and his administration were like quite devoted they would be able to go out there and, figure out the limits of 338 or figure out the limits of of 301?

Jonas Nahm:

[10:17] Yeah, I mean, I think one thing to also think about is what is the purpose of these tariffs? Right. And so I think the justifications from the administration have been varied and changed over time. But, you know, they’ve taken in a significant amount of revenue, some 30 billion dollars a month from these tariffs. This was about four times as much as in the Biden administration. And so there is some money coming in from this. And so 122, the 10% immediately, would bring back some of that revenue that is otherwise lost. One question is what’s going to happen to refunds from the IEEPA tariffs? Are they going to have to pay this back? It seems like that’s also kind of a court battle that needs to be fought out. And the Supreme Court didn’t weigh in on that. But, you know, the estimates show that if you brought the 122 in at 10%, you would actually recoup a lot of the money that you would otherwise lose and the effective tariff rate in the U.S. Would go back from 10% to about 15%, roughly to where it was before the Supreme Court ruled on it.

Robinson Meyer:

[11:18] Has the effect of tariffs from the Trump administration been larger or smaller than what you thought it would be? Not necessarily in the immediate aftermath of “liberation day”, because he announced these giant tariffs and then kind of walked some of them back. But like the tariff rate has gone up a lot in the past year. Has the effect of that on the economy been more or less than you expected?

Jonas Nahm:

[11:43] I think that the industrial policy justification that they have also used is a completely different bucket. Right. So you can use this for revenue and then you can just sort of tax different sectors at different times as long as the sum overall is what you want it to be. From an industrial policy perspective, all of this uncertainty is not very helpful because if you’re thinking about companies making major investment decisions and you have this IEEPA Supreme Court case sort of hanging over the situation for the past year, now we don’t know exactly what they’re going to replace it with, but you’re making a $10 billion decision to build a new manufacturing plant. You may want to sit that out until you know what exactly the environment is and also what the environment is for the components that you need to import, right? So a lot of U.S. imports actually go into domestic manufacturing. And so it’s not just the product that we’re trying to kind of compete with by making it domestically, but also the inputs that we need to make that product here that are being affected.

Jonas Nahm:

[12:38] And so for those kinds of supply chain rewiring industrial policy decisions, you probably want a lot more certainty than we’ve had. And so the Supreme Court ruling against the IEEPA tariff justification is certainly more certainty in all of this. So we’ve now taken that off the list. But we are not clear what the new environment will look like and how long it’s going to stick around. And so from sort of an industrial policy perspective, that’s not really what you want. Ideally, what you would have is very predictable tariffs that give companies time to become competitive without the competition from abroad, and then also a very credible commitment to taking these tariffs away at some point so that the companies have an incentive to become competitive behind the tariff wall and then compete on their own. That’s sort of the ideal case. And we’re somewhat far from the ideal case. Given the uncertainty, given the lack of clarity on whether these things are going to stick around or not, or might be extended forever, and sort of the politics in the U.S. that make it much harder to take tariffs away than to impose them.

Robinson Meyer:

[15:26] I have heard from Democrats and like Democratic economic policymaker making staff, let’s say, that they really did believe that when Trump announced all these tariffs, that what people said it was going to crash the economy. And the fact that it like hasn’t necessarily crashed the economy has made some of them go, huh, well, maybe tariffs aren’t as bad as we kind of were told they were. And we should consider them as part of a broader economic playbook. Looking over the past year, have you been surprised by how resilient the U.S. economy has been despite all these new trade restrictions that didn’t exist two years ago?

Jonas Nahm:

[16:04] I think the answer to that question really depends on what you’re looking at specifically, right? So if this was supposed to be a manufacturing reshoring tool, in some ways it’s too early to tell whether it’ll work. We’ve seen this during the Biden administration. The Inflation Reduction Act came out. And by the time the election rolled around, a lot of these plants were still under construction. So in some ways, the theory was still untested on whether

Jonas Nahm:

[16:28] that would have changed people’s voting behavior, because we didn’t have enough time. And so in the same way, we don’t have enough time now. And we’ve seen manufacturing job losses over the last year, things have picked up a little bit recently, and sort of capacity utilization is up this month, or last month, rather in the U.S.. But I think that is from using existing plants more rather than building new ones in response to the tariffs. And of course, there are big announcements that have been made where companies that were going to build a plant in Canada are now building it in the U.S.. And some changes in decision-making have occurred as a result of it. But I think to really judge this as a sort of reassuring manufacturing industrial policy, it’s just too early. And I think the uncertainty really also then prolongs the period that it would take for companies to really do this. I mean, you’d want to think about that decision quite carefully. And while a lot of this stuff is still ongoing, I think companies have just avoided making big decisions.

Robinson Meyer:

[17:27] It’s also unclear to me how much of American trade tariffs actually did fall on in terms of specific bilateral relationships. So to be specific, like we talk about these fentanyl tariffs, which is the president’s name for what he said were 25% tariffs on Canada and Mexico and 10% tariffs on China and 10% tariffs on Canadian energy exports. And what, Those are big numbers, but what wound up happening in the immediate aftermath of his initial decision was that trade previously authorized under USMCA, the successor to NAFTA, was exempted or wasn’t fully subject to that tariff. And what that meant is that basically, for instance, no Canadian oil exports have ever been subject to this 10% tariff. It’s totally trade as normal between the two countries, at least on an energy basis, and yet. But notionally on the books, there is a threat of a much higher tariff, I suppose, if the president were to change his mind or in the future.

Jonas Nahm:

[18:31] I think you raise a really good point also because the effective tariff rate was around 15 or 16% or so, much lower than some of these headline numbers that were being thrown around. And that’s because we’ve exempted a lot of stuff, right? So coffee prices went up and we exempted Brazilian coffee imports. And we’ve taken other key industries out of this calculation. And USMCA-compliant goods were exempted from the fentanyl tariffs on Canada and Mexico. And so overall, the sort of number of products that are being impacted are much smaller than everything. And one of the interesting questions I think now is, for instance, in the Section 122 10% game that they’re trying to play, the process for exempting and excluding certain products works differently. And so if this really becomes a universal 10%, it would actually affect a lot of things that currently aren’t being tariffed by the reciprocal tariffs. And they don’t have a lot of time. So maybe that also plays into it where they don’t have the capacity to really plan it out strategically. And so if we’re now then moving to a world where a lot of critical inputs into domestic manufacturing are being tariffed at 10% that were previously exempt, that might have some negative consequences for the manufacturers that are trying to survive and all of this uncertainty.

Robinson Meyer:

[19:49] I guess that also removes like a huge opportunity for corruption, because one thing that would happen is the president would take not only like coffee out of the tariff. One thing that would happen is the president wouldn’t only remove tariffs on product categories like coffee, but he would just remove them from companies or put them back on other companies. And it seemed like this huge black box of potential corruption that there just wasn’t a lot of visibility into.

Robinson Meyer:

[20:17] Let’s talk about the sectors that we follow here. So what does this Supreme Court case mean, if anything, for electric vehicles?

Jonas Nahm:

[20:28] Maybe before we jump into this, just to remind everyone, so we’ve taken away one layer of this kind of cake of tariffs that we’ve built here over time. There’s Section 301, there’s Section 232s, there’s anti-dumping and countervailing duties. Sometimes there’s safeguards, Section 201. And so all of those things can apply to the same product. And so we’re sort of taking one piece out of that stack, but it means the others are still there.

Robinson Meyer:

[20:52] And crucially, this is not like a supermarket sheet cake with two layers or even a pound cake like you might.

Jonas Nahm:

[20:59] Make at home. No, it’s a fancy cake.

Robinson Meyer:

[21:00] It’s a Russian honey cake with 12 or 13 layers stacked upon each other of delectable trade-fine goodness.

Jonas Nahm:

[21:09] That’s exactly right. And so if we think about EVs, for instance, the European companies actually aren’t being tariffed under IEEPA. They’re tariffed under Section 232 for autos and parts, which is a totally different legal foundation. And so they are not benefiting from IEEPA going away. They might now get hit with 122s on top of what they were paying previously if that isn’t designed carefully. And so there’s a lot of open questions about what that actually looks like in practice, but it’s certainly not helping them. On the China side, which is probably our bigger concern, is that electric vehicles are already in the Section 301 penalty box and they get 100% on EVs and there’s tariffs on batteries under 301. So IEEPA was there with 10% for these products, but it wasn’t really the significant piece. And so I think there it doesn’t fundamentally change the landscape. But the problem, I think, is more that we have uncertainty and there’s this constant turmoil over what it’s going to be. And we have four meetings between Xi and Trump lined up for the year and he’s supposed to go there at the end of March and lots of uncertainty sort of in the policy space that IEEPA kind of feeds into, but wasn’t really that critical, I think.

Jonas Nahm:

[22:23] And on China specifically, the U.S.TR, the Office of the Trade Representative, launched in the fall a Section 301 investigation on China saying that they hadn’t adhered to the requirements of the phase one trade deal from the first Trump administration. They held the public hearings. They probably have a report ready to go. So they could reimpose also kind of on a national level 301 tariffs on China based on this finding, which could more than offset the loss of the Aiba tariffs.

Robinson Meyer:

[22:53] Okay, next sector. So what does this mean for solar? Because one interesting subplot here that my colleague Matt Zeitlin was talking about earlier today is that after “liberation day”, Wall Street became very convinced that First Solar, this U.S. solar manufacturing firm, was going to be the huge beneficiary of this new Trumpian tariff regime. And it really has not been at all. It’s like, it turned out that a lot of its inputs had new tariffs on them, that it really didn’t affect its business very much. But there are a lot of tariffs on solar. Are they that go back all the way to the Biden administration or the first Trump administration? Were those issued under IEEPA? And what is their current status?

Jonas Nahm:

[23:36] Solar was affected by the IEEPA layer in China, for instance, but there are other tariffs in place that are much more significant. And then on China and also Southeast Asian suppliers, there are anti-dumping and countervailing duties in place that are issued to specific companies. And so the rate kind of depends on which company, but some of them are over 200%. So there you might have a loophole that like a new supplier springs up that isn’t yet affected by this countervailing duty regime. And so they might benefit. But I think there are two, the IEEPA story is only one layer. We had Section 201 safeguards on solar that I think were expiring in February this year. So that layer was ending and now IEEPA is ending. But Section 301 on China and the ADECVDs remain in place and I think are going

Jonas Nahm:

[24:26] to make it unlikely that we see the sudden onslaught of Chinese supply.

Robinson Meyer:

[24:30] Are there any other kind of sectors to talk about here, you know, really affected by this or, I don’t know, data center inputs?

Jonas Nahm:

[24:41] Wind, I think, was exposed to the IEEPA layer to some degree, but I think the other question is more broadly, what are we doing with the domestic wind industry? There’s also a 232 national security investigation that is ongoing on wind that they could switch to as a justification, both on wind turbines and turbine parts. And so there, I think we might see some sort of temporary IEEPA relief, especially for inputs like metals and so on that are now coming in, perhaps at different prices. I don’t know if that can really help the wind industry overcome the broader headwinds that they’re facing with this administration. But, you know, if there is a real positive impact, I would expect them to very quickly switch to the 232 justification to make up for it. I think on data centers, it’s interesting.

Jonas Nahm:

[25:29] Data centers import a huge amount of equipment, right? So servers, networking, equipment, power distribution, cooling, switch, there’s all this stuff that goes into a data center. And if IEEPA went away and nothing replaces it, that might actually be a meaningful relief for a lot of that stack. But now under this 10% 122 surcharge, it’s coming back. And if some of these exemptions that we had in place for some of these components in order to support domestic data center build out are not included, and we have to see how they actually implement this, this could be quite negative. But to me, this is really a story at this point of thinking about this way more as a revenue source than a strategic industrial policy that’s trying to reshore certain sectors. And the more we change it up and switch from one authority to another, the more it becomes a revenue story because the actual economic impact in terms of reshoring is going to be less and less.

Robinson Meyer:

[26:22] So one thing I’m taking from this conversation is that while clean energy and energy inputs might get a tiny bit of relief, largely they were already subject to this existing stack of pre-existing tariff authorities under other laws. And so they might benefit from like some economic tailwinds from this, but it’s not like Chinese or Southeast Asian solar panels are going to suddenly

Robinson Meyer:

[26:50] be available in the United States at cost. Stepping back then, what is your read of how this ruling fits into the Trump administration’s trade policy, and I think broadly, America’s attempt to formulate some kind of industrial policy that now started with the first Trump administration, was continued and changed by the Biden administration, and now soldiers on under the second Trump administration.

Jonas Nahm:

[27:19] If I think about this broadly in terms of sort of economic policymaking, the tariffs are one tool you can use to shape the nature and structure and composition of the domestic economy. In many ways, what I think is much more important is what do you do behind the tariff wall to really help companies build competitive manufacturing capacity, for instance, right? And the tariffs themselves are not really enough to do much there. And a lot of the incentives and sort of support that, for instance, the Inflation Reduction Act included, that have been taken away or it’s shortened significantly. And so we’re doing kind of less on the domestic economy and we’re doing more at the border. But I think ideally you would do

Jonas Nahm:

[28:08] Much more certainty at the border, and then combine it with a domestic strategy. And I think we’re seeing some of this now happen kind of in the critical mineral space, you know, Vault, Forge, all these kinds of new initiatives that are being pushed out by the administration to look at the demand side, and kind of create more stable markets for these technologies, for instance. So slow beginnings of kind of the supply side and demand side match in pairing different industrial policy tools. But in some ways, I think this tariff game has been a huge distraction from the actual work that we need to do on vocational training, on financing for manufacturing, on creating stable demand for these technologies that we want to make domestically so that companies can get financing and invest. And so looking at trade policy in that kind of broader picture, it looks more like a revenue policy than an industrial policy because it’s not really coordinated with these other elements.

Robinson Meyer:

[29:05] I think we’ll have to leave it there. Jonas Nahm, thank you so much.

Jonas Nahm:

[29:09] Thank you for having me on.

Robinson Meyer:

[29:14] And that will do it for us today. Thank you so much for joining us on this special weekend emergency edition of Shift Key. If you enjoyed Shift Key, then leave us a review or send this episode to your friends. You can follow me on X or Bluesky or LinkedIn, all of the above, under my name, Robinson Meyer. We’ll be back next week with at least one new episode of Shift Key for you until then Shift Key is a production of Heatmap News. Our editors are Jillian Goodman and Nico Lauricella, multimedia editing audio engineering is by Jacob Lambert and by Nick Woodbury. Our music is by Adam Kromelow. Thanks so much for listening and see you next week.

NineDot Energy’s nine-fiigure bet on New York City is a huge sign from the marketplace.

Battery storage is moving full steam ahead in the Big Apple under new Mayor Zohran Mamdani.

NineDot Energy, the city’s largest battery storage developer, just raised more than $430 million in debt financing for 28 projects across the metro area, bringing the company’s overall project pipeline to more than 60 battery storage facilities across every borough except Manhattan. It’s a huge sign from the marketplace that investors remain confident the flashpoints in recent years over individual battery projects in New York City may fail to halt development overall. In an interview with me on Tuesday, NineDot CEO David Arfin said as much. “The last administration, the Adams administration, was very supportive of the transition to clean energy. We expect the Mamdani administration to be similar.”

It’s a big deal given that a year ago, the Moss Landing battery fire in California sparked a wave of fresh battery restrictions at the local level. We’ve been able to track at least seven battery storage fights in the boroughs so far, but we wouldn’t be surprised if the number was even higher. In other words, risk remains evident all over the place.

Asked where the fears over battery storage are heading, Arfin said it's “really hard to tell.”

“As we create more facts on the ground and have more operating batteries in New York, people will gain confidence or have less fear over how these systems operate and the positive nature of them,” he told me. “Infrastructure projects will introduce concern and reasonably so – people should know what’s going on there, what has been done to protect public safety. We share that concern. So I think the future is very bright for being able to build the cleaner infrastructure of the future, but it's not a straightforward path.”

In terms of new policy threats for development, local lawmakers are trying to create new setback requirements and bond rules. Sam Pirozzolo, a Staten Island area assemblyman, has been one of the local politicians most vocally opposed to battery storage without new regulations in place, citing how close projects can be to residences, because it's all happening in a city.

“If I was the CEO of NineDot I would probably be doing the same thing they’re doing now, and that is making sure my company is profitable,” Pirozzolo told me, explaining that in private conversations with the company, he’s made it clear his stance is that Staten Islanders “take the liability and no profit – you’re going to give money to the city of New York but not Staten Island.”

But onlookers also view the NineDot debt financing as a vote of confidence and believe the Mamdani administration may be better able to tackle the various little bouts of hysterics happening today over battery storage. Former mayor Eric Adams did have the City of Yes policy, which allowed for streamlined permitting. However, he didn’t use his pulpit to assuage battery fears. The hope is that the new mayor will use his ample charisma to deftly dispatch these flares.

“I’d be shocked if the administration wasn’t supportive,” said Jonathan Cohen, policy director for NY SEIA, stating Mamdani “has proven to be one of the most effective messengers in New York City politics in a long time and I think his success shows that for at least the majority of folks who turned out in the election, he is a trusted voice. It is an exercise that he has the tools to make this argument.”

City Hall couldn’t be reached for comment on this story. But it’s worth noting the likeliest pathway to any fresh action will come from the city council, then upwards. Hearings on potential legislation around battery storage siting only began late last year. In those hearings, it appears policymakers are erring on the side of safety instead of blanket restrictions.