You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

When there’s no way out, should we go down?

On August 20, 1910, a “battering ram of forced air” swept across the plains of western Idaho and collided with several of the hundreds of small wildfires that had been left to simmer in the Bitterroot Mountains by the five-year-old U.S. Forest Service.

By the time the wind-fanned flames reached the trees above the mining town of Wallace, Idaho, later that day, the sky was so dark from smoke that it would go on to prevent ships 500 miles away from navigating by the stars. A forest ranger named Ed Pulaski was working on the ridge above Wallace with his crew cutting fire lines when the Big Blowup bore down on them and he realized they wouldn’t be able to outrun the flames.

And so, in what is now wildland firefighting legend, Pulaski drove his men underground.

Sheltering from a forest fire in an abandoned mineshaft was far from ideal: Pulaski held the panicked men at gunpoint to keep them from dashing back out into the fire, and he and the others eventually fell unconscious from smoke inhalation. But even now, more than a century later, there are few good options available for people who become trapped during wildfires, a problem that has caused some emergency managers, rural citizens, and entrepreneurs to consider similarly desperate — and subterranean — options.

“We have standards for tornado shelters,” Alexander Maranghides, a fire protection engineer at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and the author of a major ongoing assessment of the deadly 2018 Camp fire in Paradise, California, told me. “We don’t have anything right now for fire shelters.”

That’s partially because, in the United States, evacuation has long been the preferred emergency response to wildfires that pose a threat to human life. But there are times when that method fails. Evacuation notification systems can be glitchy or the alerts sent too late. Roads get cut off and people get trapped trying to get out of their neighborhoods. Residents, for whatever reason, are unable to respond quickly to an evacuation notice, or they unwisely decide to “wait and see” if the fire gets bad, and by then it’s too late. “If you can get out, you always want to get out,” Maranghides said. “But if you cannot get out, you don’t want to burn in your car. You want to have another option and among them — I’m not going to call it a ‘Plan B,’ I’m going to call it the ‘Plan A-2.’ Because we need to plan for those zero notification events.”

One promising, albeit harrowing, option has been TRAs, or “temporary refuge shelters” — typically unplanned, open areas along evacuation routes like parking lots where trapped citizens can gather and be defended by firefighters. Hardening places like schools or hospitals so they can serve as refuges of last resort is also an option, though it’s difficult and complex and, if done improperly, can actually add fuel for the fire.

Beyond that, you start getting into more outside-the-box ideas.

Tom Cova is one such thinker. He has been studying wildfire evacuations for three decades, and when I spoke to him recently to discuss the problem of traffic jams during fire evacuations, he told me that in Australia, “they have fire bunkers — private bunkers that are kind of like Cold War bunkers in the backyard, designed to shelter [people] for a few minutes if the fire’s passing.”

Unbeknownst to me at the time, Cova has even gone on record to say he’d consider one for himself if he lived on a dead-end road in California’s chaparral country. “My family and I would not get in our car and try to navigate the smoke and flames with bumper-to-bumper taillights,” he told the Los Angeles Times back in 2008. “We would just calmly open up, just like they do in Tornado Alley — open the trap door and head downstairs. Wait 20 minutes, maybe less, and come back and extinguish the embers around the home.”

Get one great climate story in your inbox every day:

Bunker-curious Americans can get easily discouraged, though. For one thing, Australia’s bushfires burn through areas fast; if you’re sheltering underground from an American forest fire, you could be in your bunker for considerably longer. For another, there are very few guidelines available for such bunkers and as of yet, no U.S. regulations; even Australia, where there are standards, generally recommends against using fire bunkers except at the highest-risk sites. Then there is the fact that there is almost no existing American fire bunker market if you wanted to buy one, anyway. “You would think more people would have wildfire shelters, but they don’t,” Ron Hubbard, the CEO of Atlas Survival Shelters, told me. “Even when there was a big fire not that many years ago and all those people died in Paradise … it has never kicked in.”

Hubbard is technically in the nuclear fallout shelter business, though he’s found a niche market selling a paired-down version of his marquee survival cellar, the GarNado, to people in wildfire-prone areas. “How many do I sell a year? It’s not a lot,” he admitted. “I thought it would have been a lot more. You’d think I’d have sold hundreds of them, but I doubt — I’d be lucky if I sell 10 in a year.” Another retailer I spoke to, Natural Disaster Survival Products, offers “inground fire safety shelters” but told me that despite some active interest, “no one has bought one yet. They are expensive and not affordable for many.”

Installing a Wildfire Bunkerwww.youtube.com

Hubbard stands by his bunker’s design, which uses a two-door system similar to what is recommended by Diamond, California’s Oak Hill Fire Safe Council, one of the few U.S. fire councils that has issued fire bunker guidance. The idea is that the double doors (and the underground chamber, insulated by piled soil) will help to minimize exposure to the radiant heat from wildfires, which can reach up to 2,000 degrees. It’s typically this superheated air, not the flames themselves, that kills you during a wildfire; one breath can singe your lungs so badly that you suffocate. “Imagine moving closer and closer to a whistling kettle, through its steam, until finally your lips wrap themselves around the spout and you suck in with deep and frequent breaths,” Matthew Desmond describes vividly and gruesomely in his book On the Fireline.

This is also why proper installation and maintenance are essential when it comes to the effectiveness of a bunker: The area around the shelter needs to be kept totally clear, like a helicopter landing pad, Hubbard stressed. “You’d be stupid to put a fire shelter underneath a giant oak tree that’s gonna burn for six hours,” he pointed out.

If there is “a weakness, an Achilles heel of the shelter,” though, “it’s the amount of air that’s inside it,” Hubbard said. Since wildfire shelters have to be airtight to protect against smoke and toxic gases, it means you only have a limited time before you begin to risk suffocation inside. You can extend the clock, theoretically, by using oxygen tanks, although this is part of the reason Australia tends to recommend against fire bunkers in all but the most extreme cases: “Getting to a tiny bunker and relying on cans of air in very unpleasant conditions and being unable to see out and monitor things would be a very unpleasant few hours,” Alan March, an urban planning professor at the University of Melbourne, once told the Los Angeles Times.

Private fire bunkers, with their limited capacities, can start to feel like they epitomize the every-man-for-himself mentality that has gotten some wildfire-prone communities into this mess in the first place. Something I’ve heard over and over again from fire experts is that planning for wildfire can’t happen only at the individual level. NIST’s Maranghides explained, for example, that “if you move your shelter away from your house, but it’s next to the neighbor’s house, and your neighbor’s house catches on fire, preventing you from using your shelter, you’re going to have a problem.” A bigger-picture view is almost always necessary, whether it’s clearing roadside vegetation along exit routes or creating pre-planned and identifiable safety zones within a neighborhood.

To that end, bunkers are far from a community-level solution — it’s impractical to have a cavernous, airtight, underground chamber by the local school filled with 1,000 oxygen tanks — and they’re not a realistic option for most homeowners in rural communities, either. Beyond requiring a large eyesore of cleared space for installation on one’s property, they’re expensive; Hubbard’s fire shelter starts at $30,000, and that’s before the oxygen tanks and masks (and the training and maintenance involved in using such equipment) are added.

The biggest concern of all when it comes to wildfire bunkers, though, might be the false sense of security they give their owners. Evacuation notice compliance is already a problem for fire managers; by some estimates, as many as three-quarters of people in wildfire communities hesitate or outright ignore evacuation notices when they are issued, even when not immediately evacuating is one of the most dangerous things you can do. But by having a shelter in one’s backyard, people may start to feel overconfident about their safety and linger longer, or decide outright to “shelter in place,” putting themselves and first responders in unnecessary danger.

As far as Hubbard is aware, no one has actually ridden out a wildfire in one of his shelters yet (people tend to install them, and then he never hears from them again). But there have been reported cases of homemade fire bunkers failing, including a retired firefighter who perished in a cement bunker on his property with his wife in Colorado’s East Troublesome fire in 2020.

Even Pulaski’s celebrated escape down the mineshaft resulted in tragedy. Though the forest ranger is remembered as a hero for his quick thinking and the 40 men he saved from the Big Blowup, the stories tend to gloss over the five men who either suffocated or drowned in the shallow water in the mine while unconscious from the smoke.

Some things just don’t change over 100 years: You will always have the greatest chance of surviving a fire by not being in one at all.

Read more about wildfires:

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Current conditions: The bomb cyclone barrelling toward the East Coast is set to dump up to 6 inches of snow on North Carolina in one of the state’s heaviest snowfalls in decades • The Arctic cold and heavy snow that came last weekend has already left more than 50 people dead across the United States • Heavy rain in the Central African Republic is worsening flooding and escalating tensions on the country’s border with war-ravaged Sudan.

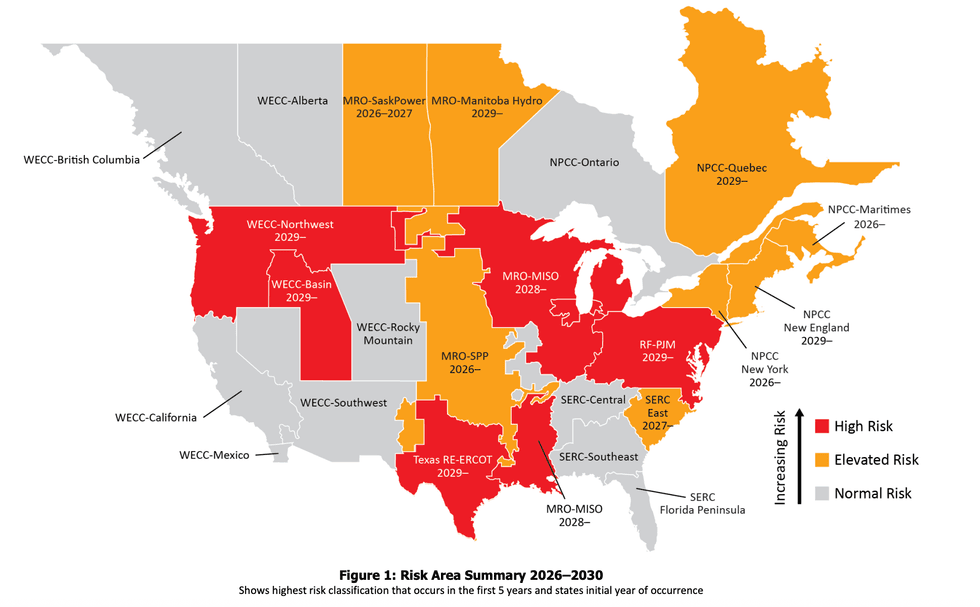

Every year, the North American Electric Reliability Corporation — a quasi-governmental watchdog group that monitors the health of the power grids in the United States and Canada — publishes its analysis of where things are headed. The 2025 report just came out, and America is bathed in a sea of red. The short of it: Electricity demand is on track to outpace supply throughout much of the country. The grids that span the Midwest, Texas, the Northwest, and the Mid-Atlantic face high risks — code red for reliability. The systems in the Northeast, the Carolinas, the Great Plains, and broad swaths of Canada all face elevated risk over the next four years. The failure to build power plants quickly enough to meet surging demand is just one issue. NERC warned that some grids, such as those in the Pacific Northwest, the Mountain West, and Great Basin states, are staring down potential instability from the addition of primarily weather-dependent renewables such as solar panels and wind turbines that, absent batteries and grid-forming technologies, make managing systems built around firm sources such as coal and hydroelectricity harder to balance.

There’s irony there. Solar and wind are among the fastest new generating sources to build. They’re among the cheapest, too, when you consider how expensive turbines for gas plants have grown as manufacturers’ backlogs stretch to the end of the decade. But they’re up against a Trump administration that’s phasing out tax credits and refusing to permit projects — even canceling solar megaprojects that would have matched the capacity of large nuclear stations. The latest tactic, as my colleague Jael Holzman described in a scoop last night, involves challenging the aesthetic value of wind and solar installations.

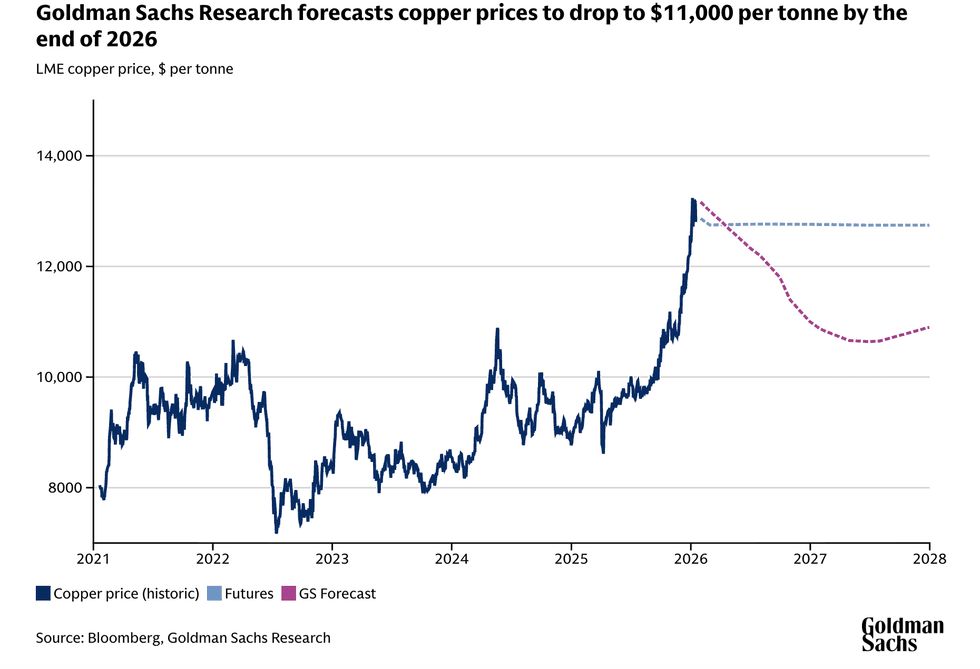

Copper prices just surged by the most in more than 16 years after what Bloomberg pegged to a “wave of buying from Chinese investors” that “triggered one of the most dramatic moves in the market’s history.” Prices surged as much as 11% to above $14,500 per ton for the first time before falling somewhat. It was enough to earn headlines about “metals mania” and “absolutely bonkers” pricing. The metal is used in virtually every electrical application. Between China commencing its march toward becoming the world’s first “electrostate” and U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell signaling a stronger American economy than previously thought, investors are betting on demand for copper to keep growing. For now, however, the prices on copper futures contracts are already leveling off, and Goldman Sachs forecasts the price to fall before stabilizing at a level still well above the average over the last four years.

Amid the volatility, the Trump administration may be shying away from a key tool used to make investments in new mines less risky. On Thursday, Reuters reported that two senior Trump officials told U.S. minerals executives that their projects would need to prove financial independence without the federal government guaranteeing a minimum price for what they mine. “We’re not here to prop you guys up,” Audrey Robertson, assistant secretary of the Department of Energy and head of its Office of Critical Minerals and Energy Innovation, reportedly told the executives gathered at a closed-door meeting hosted by a Washington think tank earlier this month. “Don’t come to us expecting that.” The Energy Department said that Reuters’ reporting is “false and relies on unnamed sources that are either misinformed or deliberately misleading.” At least one mining startup, United States Antimony Corporation, and a mining economist have echoed the administration’s criticism. One tool the Trump administration certainly isn’t wavering on is quasi nationalization. Just two days ago I was telling you about the latest company, USA Rare Earth, to give the government an equity stake in exchange for federal financing.

Get Heatmap AM directly in your inbox every morning:

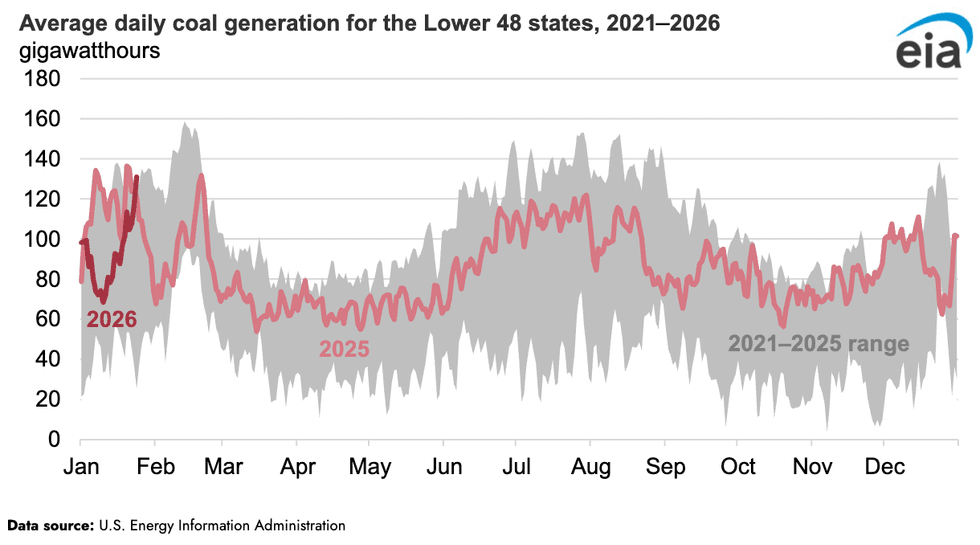

Coal-fired electricity generation in the Lower 48 states soared 31% last week compared to the previous week amid Winter Storm Fern’s Arctic temperatures, according to a new analysis by the Energy Information Administration. It’s a stark contrast from the start of the month, when milder temperatures led to lower coal-fired power production versus the same period in 2025. Natural gas generation also surged 14% compared to the previous week. Solar, wind, and hydropower all declined. Nuclear generation remained nearly unchanged.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

The specter of an incident known as “whoops” haunts the nuclear industry. Back in the 1980s, the Washington Public Power Supply System attempted to build several different types of reactors all at once, and ended up making history with the biggest municipal bond default in U.S. history at that point. The lesson? Stick to one design, and build it over and over again in fleets so you can benefit from the same supply chain and workforce and bring down costs. That, after all, is how China, Russia, and South Korea successfully build reactors on time and on budget. Now Jeff Bezos’ climate group is backing an effort to get the Americans to adopt that approach. On Thursday, the Bezos Earth Fund gave a $3.5 million grant to the Nuclear Scaling Initiative, a partnership between the Clean Air Task Force, the EFI Foundation, and the Nuclear Threat Initiative. In a statement, the philanthropy’s chief executive, Tom Taylor, called the grant “a targeted bet that smart coordination can unlock much larger public and private investment and turn this first reactor package into a model for many more.” Steve Comello, the executive director at the Nuclear Scaling Initiative, said the “United States needs repeat nuclear energy builds — not one off projects — to bolster energy security, improve grid reliability, and drive economic competitiveness.”

The Netherlands must write stricter emissions-cutting targets into its laws to align with the Paris Agreement in the name of protecting Bonaire, one of its Caribbean island territories, from the effects of climate change. That’s according to a Wednesday ruling by the District Court of The Hague in a case brought by Greenpeace. The decision also found that Amsterdam was discriminating against residents of the island by failing to do enough to help the island adapt to the existing effects of global warming, including sea-level rise, flooding, and extreme weather. Bonaire is the largest and most populous of the trio of islands that form the Dutch Caribbean territory and includes Sint Eustatius and Saba. The lawsuit, the Financial Times noted, was “one of the first to test climate obligations on a national level.”

The least ecologically destructive minerals to harvest for batteries and other technologies come not from the ground but from old batteries and materials that can be recycled. Recyclers can also get supply up and running faster than a mine can open. With the U.S. aggressively seeking supplies of rare earths that don’t come from China, the recycling startup Cyclic Materials sees an opportunity. The company is investing $82 million to build its second and largest plant. At full capacity, the first phase of the new facility in South Carolina will process 2,000 metric tons of magnet material per year. But the firm plans to eventually expand to 6,000 tons.

Pennsylvania is out, Virginia wants in, and New Jersey is treating it like a piggybank.

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative has been quietly accelerating the energy transition in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast since 2005. Lately, however, the noise around the carbon market has gotten louder as many of the compact’s member states have seen rising energy prices dominate their local politics.

What is RGGI, exactly? How does it work? And what does it have to do with the race for the 2028 Democratic presidential nomination?

Read on:

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative is a cap and trade market with roots in a multistate compact formed in 2005 involving Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, and Vermont.

The goal was to reduce emissions, and the mechanism would be regular auctions for emissions “allowances,” which large carbon-emitting electricity generators would have to purchase at auction. Over time, the total number of allowances in circulation would shrink, making each one more expensive and encouraging companies to reduce their emissions. The cap started at 188 million short tons of carbon and has been dropping steadily ever since, with an eventual target of under 10 million by 2037.

By the time of the first auction in 2008, six states were fully participating — Delaware, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and New York were out; Maryland, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island were in — and together they raised almost $39 million. By the second auction later that year, 10 states — the six from the previous auction, plus New York, New Jersey, New Hampshire, and Delaware — were fully participating.

Membership has grown and shrunk over the years (for reasons we’ll cover below) but the current makeup is the same as it was at the end of 2008.

When carbon pricing schemes were first dreamt up by economists, the basic thinking was that by taxing something bad (carbon emissions) you could reduce taxes on something good (like wages or income). Real existing carbon pricing schemes, however, have tended to put their proceeds toward further decarbonization rather than reducing taxes or other costs.

In the case of the RGGI, the bulk of revenue goes to fund state climate programs. About two-thirds of investments from RGGI revenues in 2023 went to energy efficiency programs, which have received 56% of the system’s cumulative investments. By contrast, 15% of the 2023 investments (and 15% of the all-time investments) went to “direct bill assistance,” i.e. lowering utility bills.

Carbon dioxide emissions from the power sector have fallen by 40% to 50% in the RGGI territory since the program began — faster than in the U.S. as a whole.

That’s in part because the areas covered by RGGI have seen some of the sharpest transitions away from coal-fired power. New England, for instance, saw its last coal plant shut down late last year.

But it’s not always easy to figure out what was the effect of RGGI versus broader shifts in the energy industry. In the emissions-trading system’s early years, allowance prices were very low, and actual emissions fell well below the cap. That was largely due to factors affecting the country as a whole, including sluggish demand growth for electricity. The fracking boom also sent natural gas prices plunging, accelerating the switch from coal to gas and decelerating carbon dioxide emissions from the power sector (although this effect may have been more limited in the RGGI region, much of which has insufficient natural gas pipeline capacity).

That said, RGGI still might have helped tip the scales, Dallas Burtraw, a senior fellow at Resources for the Future, told me.

“It takes only a modest carbon price to really push out coal,” he said, pointing to the experience of RGGI and arguing that it could be replicated in other states. A 2016 paper by Man-Kuen Kim and Taehoo kim published in Energy Economics found “strong evidence that coal to gas switching has been actually accelerated by RGGI implementation.”

That trick doesn’t work as well now as it used to, though. “For the first 10 years or so, the primary margin for achieving emission reductions was substitution from coal to gas,” Burtraw told me. Then renewables prices began to drop “precipitously” in the early 2010s, opening up the opportunity for more thoroughgoing decarbonization beyond just getting rid of coal. “Going forward, I think program advocates would say that now you’re seeing the move from gas to renewables with storage,” he said.

When RGGI went through its regular program review in 2012 (these happen every few years; the third was completed last year), the target had to be wrenched downward to account for the actual path of emissions, which had dropped far more quickly than the cap.

“Soon after the start of RGGI, it became apparent that the number of allowances in the emissions budget was higher than actual emissions. Allowance prices consequently dropped, making it particularly inexpensive to purchase allowances and bank them for use in later periods,” a case study published by the Environmental Defense Fund found. In other words, because there was such a gap between the proscribed cap and actual emissions, generators had been able to squirrel away enough allowances to make future caps ineffective.

The arguments against the RGGI have been relatively constant and will be familiar to anyone following debates over energy and climate policy: RGGI raises prices for consumers, its opponents say. It pushes out reliable and cheaper energy sources, and thereby threatens jobs in fossil fuel generation and infrastructure. Also the particulars of how a state joins or exits the group have often come up for debate.

Three states have proved troublesome, including one original member and two later joiners: New Jersey, Virginia, and Pennsylvania. All three states are sizable energy consumers, and Virginia and Pennsylvania have substantial fossil fuel infrastructure and production.

New Jersey quickly expressed its discontent. In 2011, New Jersey’s Republican Governor Chris Christie decided to take the state out of the market, saying that it was unnecessary and costly. Democrat Phil Murphy, Christie’s successor, brought it back in 2020 as part of a broader agenda to decarbonize New Jersey’s economy.

Pennsylvania attempted to join next, in 2019, but ran into legal hurdles almost immediately. Governor Tom Wolf, a Democrat, issued an executive order in 2019 to set up carbon trading in the state, and state regulators got to work drawing up rules to allow Pennsylvania to link up with RGGI, formally joining in 2022.

But the following year, a Pennsylvania court ruled that the state was not able to participate because the regulatory work ordered by Wolf had been approved by the legislature. The case worked its way up to the state’s highest court last spring, but got tossed in January after Governor Josh Shapiro, a Democrat, made a budget deal with the state legislature late last year removing Pennsylvania from RGGI once and for all — more on that below.

Virginia was the last new state to join in 2020, under Democratic Governor Ralph Northam, who said that by joining, Virginia was “sending a powerful signal that our commonwealth is committed to fighting climate change and securing a clean energy future.” A year later, however, Northam lost the governorship to Republican Glenn Youngkin, who removed Virginia from RGGI at the end of 2023.

Youngkin described the exit — technically a choice made by state regulators — as a “commonsense decision by the Air Board to repeal RGGI protects Virginians from the failed program that is not only a regressive tax on families and businesses across the Commonwealth, but also does nothing to reduce pollution.”

Pennsylvania fits uneasily into the Northeastern–blue hue of the RGGI’s core states. It’s larger than any state in the system besides New York, right down the center politically, and is a substantial producer and exporter of electricity, much of it coming from fossil fuels (and nuclear power). It also has lower electricity costs than its neighbors to the east.

Pennsylvania’s governor, Josh Shapiro, is widely expected to run for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2028, and has put reining in electricity costs at the center of his messaging of late. He sued PJM, the mid-Atlantic electricity market at the end of 2024, and won a settlement to cap costs in the system’s capacity auctions. He also helped negotiate a “statement of principles” with the White House in order to potentially get those caps extended. And earlier this month, he met with utility executives “to discuss steps they can take to lower utility costs and protect consumers,” Will Simons, a spokesperson for the governor, said.

Pennsylvania’s permanent and undisputed inclusion in the RGGI system would be a coup. Unlike its neighbor RGGI states, including Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, and New York, Pennsylvania still has a meaningful coal industry, meaning that its emissions could potentially fall substantially with a modest carbon price. It would also provide some relief to the rest of the system by notching significant emissions reductions at lower cost, meaning that electricity prices would likely be minimally affected or even go down, according to research done in 2023 by Burtraw, Angela Pachon, and Maya Domeshek.

“Pennsylvania is the source of a lot of low-cost emission reductions precisely because it still retains that coal-to-gas margin,” Burtraw said. “It looks the way the Northeastern states looked 15 years ago.”

But alas, it won’t happen. As part of a budget deal with Republicans reached late last year, Pennsylvania exited RGGI. That Shapiro would be willing to sacrifice RGGI isn’t shocking considering his record — when he ran for governor in 2021, he often put more emphasis on investing in clean energy than restricting fossil fuels. As governor, he has pushed for regulatory reforms, and even a Pennsylvania-specific cap and trade program, but Senate Republicans made RGGI exit the price of any energy policy talks.

Virginia may be ready to return to the fold.

“For me, this is about cost savings,” newly installed governor Abigail Spanberger said in her inaugural address. “RGGI generated hundreds of millions of dollars for Virginia — dollars that went directly to flood mitigation, energy efficiency programs, and lowering bills for families who need help most.” Furthermore, “withdrawing from RGGI did not lower energy costs,” she said. “In fact, the opposite happened — it just took money out of Virginia’s pocket,” referring to lost gains from RGGI auctions. (Research by Burtraw, Maya Domeshek, and Karen Palmer found that RGGI participation was the “lowest-cost way” of achieving the state’s statutory emissions reductions goals and that the funded investment investments in efficiency will likely drive down household costs.)

Virginia’s newly elected Attorney General Jay Jones also reversed the position of his Republican predecessor, signing on to litigation against Youngkin’s withdrawal from the program, arguing that the governor lacked the legal authority to withdraw from the program in the first place —the inverse of Pennsylvania’s legal tangle over RGGI.

New Jersey, too, has a new governor, Democrat Mikie Sherrill. In a set of executive orders, signed before she had even finished her inaugural address, Sherrill directed New Jersey economic, environment, and utility regulatory officials to “confer about the use of Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative … proceeds for ratepayer relief,” and “include an explanation of how they intend to address ratepayer relief in the 2026-2028 RGGI Strategic Funding Plan.”

Ratepayers are already due to receive RGGI funding under New Jersey’s current strategic funding plan, as are environmental protection and energy efficiency programs, renewable and transmission investments, and a grab-bag of other climate related projects. New Jersey utility regulators last fall made a $430 million distribution to ratepayers in the form of two $50 bill credits, with additional $25 a month credits for low-income ratepayers.

The evolution of RGGI — and its use by New Jersey to reduce electricity bills in particular — shows how carbon mitigation programs have had to adapt to political realities.

“In the political context of the moment, I think it’s totally fair,” Burtraw told me of Sherrill’s plan. “It’s the worst good idea of what you can do with the carbon proceeds. Everybody in the room can come up with better ideas: Oh, we should be doing this investment, or we should be doing energy efficiency, or we should subsidize renewables. Show me that those ideas are a higher value use for that money and I’m all in. But we could at least be doing this.”

What remains to be seen is whether other states pick up the torch from Sherrill and start using RGGI as a way to more directly combat electricity price hikes. Her actions “could create ripple effects for other states that may face similar concerns,” Olivia Windorf, U.S. policy fellow at the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, told me.

While RGGI tends to be in the news in the individual states only when there’s some controversy about entering or exiting the program, “the focus on electricity prices and affordability is putting a new spotlight on it,” Windorf said.

More aggressive or creative uses of the proceeds would put RGGI closer to the center of debates around affordability. “I think it will help address affordability concerns in a way that's really tangible,” Windorf said. “So it’s not abstract how carbon markets and RGGI can help through this time of load growth and energy transition. It can be a tool rather than a burden.”

The Army Corps of Engineers is out to protect “the beauty of the Nation’s natural landscape.”

A new Trump administration policy is indefinitely delaying necessary water permits for solar and wind projects across the country, including those located entirely on private land.

The Army Corps of Engineers published a brief notice to its website in September stating that Adam Telle, the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works, had directed the agency to consider whether it should weigh a project’s “energy density” – as in the ratio of acres used for a project compared to its power generation capacity – when issuing permits and approvals. The notice ended on a vague note, stating that the Corps would also consider whether the projects “denigrate the aesthetics of America’s natural landscape.”

Prioritizing the amount of energy generation per acre will naturally benefit fossil fuel projects and diminish renewable energy, which requires larger amounts of land to provide the same level of power. The Department of the Interior used this same tactic earlier in the year to delay permits.

Now we know the full extent of the delays wrought by that notice thanks to a copy of the Army Corps’ formal guidance on issuing permits under the Clean Water Act or approvals related to the Rivers and Harbors Act, a 1899 law governing discharges into navigable waters. That guidance was made public for the first time in a lawsuit filed in December by renewable trade associations against Trump’s actions to delay, pause, or deny renewables permits.

The guidance submitted in court by the trade groups states that the Corps will scrutinize the potential energy generation per acre of any permit request from an energy project developer, as well as whether an “alternative energy generation source can deliver the same amount of generation” while making less of an impact on the “aquatic environment.” The Corps is now also prioritizing permit applications for projects “that would generate the most annual potential energy generation per acre over projects with low potential generation per acre.”

Lastly, the Corps will also scrutinize “whether activities related to the projects denigrate the beauty of the Nation’s natural landscape” when deciding whether to issue these permits. That last factor – aesthetics – is in fact a part of the Army Corps’ permitting regulations, but I have not seen any previous administration halt renewable energy permits because officials think solar farms and wind turbines are an eyesore.

Jennifer Neumann, a former career Justice Department attorney who oversaw the agency’s water-related casework with the Army Corps for a decade, told me she had never seen the Corps cite aesthetics in this way. The issue has “never really been litigated,” she said. “I have never seen a situation where the Corps has applied [this].”

The renewable energy industry’s amended complaint in the lawsuit, which is slowly proceeding in federal court, claims the Corps’ guidance will lead to “many costly project redesigns” and delays, “resulting in contract penalties, cost hikes, and deferred revenue.” Other projects “may never get their Corps individual permits and thus will need to be canceled altogether.”

In addition, executives for the trade associations submitted a sworn declaration laying out how they’re being harmed by the Corps guidance, as well as a host of other federal actions against the renewable energy sector. To illustrate those harms they laid out an example: French energy developer ENGIE, they said, was required to “re-engineer” its Empire Prairie wind and solar farm in Missouri because the guidance “effectively precludes” it from getting a permit from the Army Corps. This cost ENGIE millions of dollars, per the declaration, and extended the construction timeline while ultimately also making the project less efficient.

Notably, Empire Prairie is located entirely on private land. It isn’t entirely clear from the declaration why the project had to be redesigned, and there is scant publicly available information about it aside from a basic website. The area where Empire Prairie is being built, however, is tricky for development; segments of the project are located in counties – DeKalb and Andrew – that have 88 and 99 opposition risk scores, respectively, per Heatmap Pro.

Renewable energy developers require these water permits from the Army Corps when their construction zone includes more than half an acre of federally designated wetlands or bodies of water protected under the Rivers and Harbors Act. Neumann told me that developers with impacts of half an acre or less may skirt the need for a permit application if their project qualifies for what’s known as a “nationwide permit,” which only requires verification from the Corps that a company complies with the requirements.

Even the simple verification process for Corps permits has been short-circuited by other actions from the administration. Developers are currently unable to access a crucial database overseen by the Fish and Wildlife Service to determine whether their projects impacts species protected under the Endangered Species Act, which in turn effectively “prevents wind and solar developers from (among other things) obtaining Corps nationwide permits for their projects,” according to the declaration from trade group executives.

But hey, look on the bright side. At least the Trump administration is in the initial phases of trying to pare back federal wetlands protections. So there’s a chance that eliminating federal environmental protections might benefit some solar and wind companies out there. How many? It’s quite unclear given the ever-changing nature of wetlands designations and opaque data available on how many projects are being built within those areas.