You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

With the ongoing disaster approaching its second week, here’s where things stand.

A week ago, forecasters in Southern California warned residents of Los Angeles that conditions would be dry, windy, and conducive to wildfires. How bad things have gotten, though, has taken everyone by surprise. As of Monday morning, almost 40,000 acres of Los Angeles County have burned in six separate fires, the biggest of which, Palisades and Eaton, have yet to be fully contained. The latest red flag warning, indicating fire weather, won’t expire until Wednesday.

Many have questions about how the second-biggest city in the country is facing such unbelievable devastation (some of these questions, perhaps, being more politically motivated than others). Below, we’ve tried to collect as many answers as possible — including a bit of good news about what lies ahead.

A second Santa Ana wind event is due to set in Monday afternoon. “We’re expecting moderate Santa Ana winds over the next few days, generally in the 20 to 30 [mile per hour] range, gusting to 50, across the mountains and through the canyons,” Eric Drewitz, a meteorologist with the Forest Service, told me on Sunday. Drewitz noted that the winds will be less severe than last week’s, when the fires flared up, but he also anticipates they’ll be “more easterly,” which could blow the fires into new areas. A new red flag warning has been issued through Wednesday, signaling increased fire potential due to low humidity and high winds for several days yet.

If firefighters can prevent new flare-ups and hold back the fires through that wind event, they might be in good shape. By Friday of this week, “it looks like we could have some moderate onshore flow,” Drewitz said, when wet ocean air blows inland, which would help “build back the marine layer” and increase the relative humidity in the region, decreasing the chances of more fires. Information about the Santa Anas at that time is still uncertain — the models have been changing, and the wind is tricky to predict the strength of so far out — but an increase in humidity will at least offer some relief for the battered Ventura and Orange Counties.

The Palisades Fire, the biggest in L.A., ripped through the hilly and affluent area between Santa Monica and Malibu, including the Pacific Palisades neighborhood, the second-most expensive zip code in Los Angeles and home to many celebrities. Structures in Big Rock, a neighborhood in Malibu, have also burned. The fire has also encroached on the I-405 and the Getty Villa, and destroyed at least two homes in Mandeville Canyon, a neighborhood of multimillion-dollar homes. Students at nearby University of California, Los Angeles, were told on Friday to prepare for a possible evacuation.

The Eaton Fire, the second biggest blaze in the area, has killed 16 people in Altadena, a neighborhood near Pasadena, according to the Los Angeles Times, making it one of the deadliest fires in the modern history of California.

The 1,000-acre Kenneth fire is 100% contained but still burning near Calabasas and the gated community of Hidden Hills. The Hurst Fire has burned nearly 800 acres and is 89% contained and is still burning near Sylmar, the northernmost neighborhood in L.A. Though there are no evacuation notices for either the Kenneth or the Hurst fires, residents in the L.A. area should monitor the current conditions as the situation continues to be fluid and develop.

The 43-acre Sunset Fire, which triggered evacuations last week in Hollywood and Hollywood Hills, burned no homes and is 100% contained.

The Lidia Fire, which ignited in a remote area south of Acton, California, on Wednesday afternoon, burned 350 acres of brush and is 100% contained.

It can take years to determine the cause of a fire, and investigations typically don’t begin until after the fire is under control and the area is safe to reenter, Edward Nordskog, a retired fire investigator from the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, told Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo. He also noted, however, that urban fires are typically easier to pinpoint the cause of than wildland fires due to the availability of witnesses and surveillance footage.

The vast majority of wildfires, 85%, are caused by humans. So far, investigators have ruled out lightning — another common fire-starter — because there were no electrical storms in the area when the fires started. In the case of the Palisades Fire, there were no power lines in the area of the ignition, though investigators are now looking into an electrical transmission tower in Eaton Canyon as the possible cause of the deadly fire in Altadena. There have been rumors that arsonists started the fires, but investigators say that scenario is also pretty unlikely due to the spread of the fires and how remote the ignition areas are.

Officially, 24 people have died, but that tally is likely to rise. California Governor Gavin Newsom said Sunday that he expects “a lot more” deaths will be added to the total in the coming days as search efforts continue.

Incoming President Donald Trump slammed the response to the L.A. fires in a Truth Social post on Sunday morning: “This is one of the worst catastrophes in the history of our Country,” he wrote. “They just can’t put out the fires. What’s wrong with them?”

Though there is much blame going around — not all of it founded in reality — the challenges facing firefighters are immense. Last week, because of strong Santa Ana winds, fire crews could not drop suppressants like water or chemical retardant on the initial blazes. (In strong winds, water and retardant will blow away before they reach the flames on the ground.)

Fighting a fire in an urban or suburban area is also different from fighting one in a remote, wild area. In a true wildfire, crews don’t use much water; firefighters typically contain the blazes by creating breaks — areas cleared of vegetation that starve a fire of fuel and keep it from spreading. In an urban or suburban event, however, firefighters can’t simply hack through a neighborhood, and typically have to use water to fight structure fires. Their priority also shifts from stopping the fire to evacuating and saving people, which means putting out the fire itself has to wait.

What’s more, the L.A. area faced dangerous fire weather going into last week — with wind gusts up to 100 miles per hour and dry air — and the persistence of the Santa Ana winds during firefighting operations through the weekend made it extremely difficult for emergency managers to gain a foothold.

Trump and others have criticized Los Angeles for being unprepared for the fires, given reports that some fire hydrants ran dry or had low pressure during operations in Pacific Palisades. According to the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, about 20% of hydrants were affected, mostly at higher elevations.

The problem isn’t a lack of preparation, however. It’s that the L.A. wildfires are so large and widespread, the county’s preparations were quickly overwhelmed. “We’re fighting a wildfire with urban water systems, and that is really challenging,” Los Angeles Department of Water and Power CEO Janisse Quiñones said in a news conference last week. When houses burn down, water mains can break open. Civilians also put a strain on the system when they use hoses or sprinkler systems to try to protect their homes.

On Sunday, Judy Chu, the Democratic lawmaker representing Altadena, confirmed that fire officials had told her there was enough water to continue the battle in the days ahead. “I believe that we're in a good place right now,” she told reporters. Newsom, meanwhile, has responded to criticism over the water failure by ordering an investigation into the weak or dry hydrants.

So-called “super soaker” planes have had no problem with water access; they’re scooping directly from the ocean.

Yes. Although aerial support was grounded in the early stages of the wildfires due to severe Santa Ana winds, flights resumed during lulls in the storms last week.

There is a misconception, though, that water and retardant drops “put out” fires; they don’t. Instead, aerial support suppresses a fire so crews can get in close and use traditional methods, like cutting a fire break or spraying water. “All that up in the air, all that’s doing is allowing the firefighters [on the ground] a chance to get in,” Bobbie Scopa, a veteran firefighter and author of the memoir Both Sides of the Fire Line, told me last week.

With winds expected to pick up early this week, aerial firefighting operations may be grounded again. “If you have erratic, unpredictable winds to where you’ve got a gust spread of like 20 to 30 knots,” i.e. 23 to 35 miles per hour, “that becomes dangerous,” Dan Reese, a veteran firefighter and the founder and president of the International Wildfire Consulting Group, told me on Friday.

Because of the direction of the Santa Ana winds, wildfire smoke should mostly blow out to sea. But as winds shift, unhealthy air can blow into populated areas, affecting the health of residents.

Wildfire smoke is unhealthy, period, but urban and suburban smoke like that from the L.A. fires can be particularly detrimental. It’s not just trees and brush immolating in an urban fire, it’s also cars, and batteries, and gas tanks, and plastics, and insulation, and other nasty, chemical-filled things catching fire and sending fumes into the air. PM2.5, the inhalable particulates from wildfire smoke, contributes to thousands of excess deaths annually in the U.S.

You can read Heatmap’s guide to staying safe during extreme smoke events here.

“The bad news is, I’m not seeing any rain chances,” Drewitz, the Forest Service meteorologist, told me on Sunday. Though the marine layer will bring wetter air to the Los Angeles area on Friday, his models showed it’ll be unlikely to form precipitation.

Though some forecasters have signaled potential rain at the end of next week, the general consensus is that the odds for that are low, and that any rain there may be will be too light or short-lived to contribute meaningfully to extinguishing the fires.

The chaparral shrublands around Los Angeles are supposed to burn every 30 to 130 years. “There are high concentrations of terpenes — very flammable oils — in that vegetation; it’s made to burn,” Scopa, the veteran firefighter, told me.

What isn’t normal, though, is the amount of rain Los Angeles got ahead of this past spring — 52.46 inches in the preceding two years, the wettest period in the city’s history since the late 1800s — which was followed by a blisteringly hot summer and a delayed start to this year’s rainy season. Since October, parts of Southern California have received just 10% of their normal rainfall

This “weather whiplash” is caused by a warmer atmosphere, which means that plants will grow explosively due to the influx of rain and then dry out when the drought returns, leaving lots of dry fuels ready and waiting for a spark. “This is really, I would argue, a signature of climate change that is going to be experienced almost everywhere people actually live on Earth,” Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who authored a new study on the pattern, told The Washington Post.

We know less about how climate change may affect the Santa Anas, though experts have some theories.

At least 12,000 structures have burned so far in the fires, which is already exacerbating the strain on the Los Angeles housing market — one of the country’s tightest even before the fires — as thousands of displaced people look for new places to live. “Dozens and dozens of people are going after the same properties,” one real estate agent told the Los Angeles Times. The city has reminded businesses that price gouging — including raising rental prices more than 10% — during an emergency is against the law.

Los Angeles had a shortage of about 370,000 homes before the fires, and between 2021 and 2023, the county added fewer than 30,000 new units per year. Recovery grants and federal aid can lag, and it often takes more than two years for even the first Housing and Urban Development Disaster Recovery Grants’ expenditures to go out.

My colleague Matthew Zeitlin wrote for Heatmap that the economic impact of the Los Angeles fire is already much higher than that of other fires, such as the 2018 Camp fire, partly because of the value of the Pacific Palisades real estate.

The wildfires may “deal a devastating blow to [California’s] fragile home insurance market,” Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote last week. In recent years, home insurers have left California or declined to write new policies, at least partially due to the increased risk of wildfires in the state.

Depending on the extent of the damage from the fires, the coffers of California’s FAIR Plan — which insures homeowners who can’t get insurance otherwise, including many in Pacific Palisades and Altadena — could empty, causing it to seek money from insurers, according to the state’s regulations. As Zeitlin writes, “This would mean that Californians who were able to buy private insurance — because they don’t live in a region of the state that insurers have abandoned — could be on the hook for massive wildfire losses.”

First and foremost, sign up for all relevant emergency alerts. Make sure to turn on the sound on your phone and keep it near you in case of a change in conditions. Pack a “go bag” with essentials and consider filling your gas tank now so that you can evacuate at a moment’s notice if needed. Read our guide on what to do if you get a pre-evacuation or an evacuation notice ahead of time so that you’re not scrambling for information if you get an alert.

The free Watch Duty app has become a go-to resource for people affected by the fires, including friends and family of Angelenos who may themselves be thousands of miles away. The app provides information on fire perimeters, evacuation notices, and power outages. Its employees pull information directly from emergency responders’ radio broadcasts and sometimes beat official sources to disseminating it. If you need an endorsement: Emergency responders rely on the app, too.

There are many scams in the wake of disasters as crooks look to take advantage of desperate people — and those who want to help them. To play it safe, you can use a hub like the one established by GoFundMe, which is actively vetting campaigns related to the L.A. fires. If you’re looking to volunteer your time, make a donation of clothing or food, or if you’re able to foster animals the fire has displaced, you can use this handy database from the Mutual Aid Network L.A. There are also many national organizations, such as the Red Cross, that you can connect with if you want to help.

The City of Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Fire Department have asked that do-gooders not bring donations directly to fire stations or shelters; such actions can interfere with emergency operations. Their website provides more information about how you can help — productively — on their website.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

The Supreme Court agreed to hear Suncor Energy Inc. v. County Commissioners of Boulder County, which concerns jurisdiction for “public nuisance” claims.

A new Supreme Court case will test whether the Trump administration’s war on federal climate regulation also undercuts fossil fuel companies’ primary defense against climate-related lawsuits.

On Monday, the court agreed to weigh in on whether Boulder, Colorado’s climate change lawsuit against major oil companies is preempted by federal law. Now that the federal government has revoked its own authority to regulate greenhouse gases, the justices will have to consider whether there even is any relevant federal law to speak of.

The case is arriving at the nation’s highest court in a particularly fraught moment for climate regulation. The Supreme Court ruled back in 2007 that the EPA had authority to regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act, preventing states from creating a patchwork of their own emissions rules. The decision also shielded energy companies from federal common law “public nuisance” claims — lawsuits seeking damages for climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions.

Earlier this month, however, Trump’s EPA essentially challenged that Court decision. It made an official determination that the Clean Air Act did not, in fact, allow it to regulate emissions that have such diffuse, global effects.

“By revoking their authority on this issue, EPA, in our view, is basically eliminating what otherwise would have been a protection for companies against these kinds of lawsuits,” Andres Restrepo, a senior attorney at the Sierra Club, told me. “That really opens them up to a lot of potential legal liability and creates a lot of uncertainty.”

The new Supreme Court case dates back to 2018, when the city and county of Boulder, Colorado sued multinational oil giant ExxonMobil and Suncor, which operates the largest refinery in the state, for damages from climate change, bringing the charges under Colorado law. The oil companies tried repeatedly to get the case dismissed, arguing that it belonged in federal court. But time and again, the courts disagreed.

The Supreme Court already rejected an earlier petition to review the question of whether the case belonged in state or federal court in 2023. Now it has agreed to consider a slightly different petition, filed last summer, over whether federal law preempts Boulder’s state-law claims.

The Trump administration was acutely aware that its deregulatory moves had the potential to kick up a hornet’s nest of challenges for fossil fuel companies, so it tried to get ahead of the issue. In revoking the endangerment finding, the EPA claimed that while it “lacks statutory authority to regulate GHG emissions in response to global climate change concerns,” this has no impact on state preemption under the Clean Air Act. The agency’s final rule cites a section of that law about motor vehicle emission and fuel standards which says that states cannot adopt rules “relating to the control of emissions from new motor vehicles or new motor vehicle engines subject to this part.” In the agency’s view, this section applies broadly to any type of emission from a vehicle, whether or not the agency itself is tasked with regulating it.

The EPA also asserted that the Clean Air Act continues to preempt public nuisance claims, arguing that the Supreme Court did not base its dismissal of such claims on the EPA actually exercising any regulatory authority. The logic gets very circular here. Preemption “is no less applicable where, as here, the EPA does not regulate because Congress has not authorized such regulation as within the scope of its legal standard for determining what air pollution is dangerous and subject to regulation,” the agency wrote in its response to public comments on its initial proposal on this issue, which it published last summer.

“It feels like a bad ex-boyfriend who says, I don’t want to date you anymore, but you can’t date those other people either,” Vicki Arroyo, a law professor at Georgetown University and former Biden administration EPA official, told me.

Before the EPA finalized its decision on the endangerment finding, industry players were skittish about the legal implications. The Edison Electric Institute, the largest trade group for electric utilities, has not responded publicly to the final endangerment finding determination. It did, however, flag legal concerns in comments on the proposed rule last September, implicitly disagreeing with the EPA’s assertion that preemption was safe. It noted that the EPA’s actions could cast doubt on whether greenhouse gas emissions “remain a regulated pollutant under the Clean Air Act” in the power sector. That, in turn, could increase the likelihood that the power sector will be “further exposed to competing and conflicting regulations through a patchwork of state regulations” in addition to “the potential for increased litigation alleging common-law claims,” such as causing a public nuisance.

Automakers have also been virtually silent on the EPA’s actions. The Alliance for Automotive Innovation, the largest trade association for vehicle manufacturers, has not issued a statement on the matter. In its comments on the proposed rule, the group neither welcomed nor condemned the move. Unlike the power industry group, the automakers eagerly agreed with the EPA that rescinding the endangerment finding would not change federal preemption of state rules. It did warn, however, that eliminating greenhouse gas regulations altogether would subject the industry to yet another “rapid and dramatic” swing in policy that “puts billions of dollars of capital investment at risk.”

The only industry group I’ve seen come out firmly against the EPA’s final rule is the Zero Emissions Transportation Association, whose membership includes both automakers such as Rivian and utilities such as Duke Energy. Albert Gore, ZETA’s executive director, said in a statement that rescinding the endangerment finding “pulls the rug out from companies that have invested in manufacturing next-gen vehicles across the United States.” He also warned that it “opens businesses up to unnecessary legal risk,” including “a complicated patchwork of state regulations, threats of costly tort litigation, and inconsistent rules between markets.”

Ken Alex, a former senior assistant attorney general of California, was unequivocal that the EPA’s decision would open new avenues for public nuisance climate lawsuits. These suits are based on a complicated area of law known as federal common law, which permits courts to craft rules in very limited situations that have not been addressed by Congress. Alex represented California in the seminal 2011 Supreme Court case American Electric Power v. Connecticut, which established companies’ protection from federal public nuisance claims over greenhouse gas emissions. That decision sprang from the Court’s earlier 2007 decision that the Clean Air Act covers greenhouse gas emissions — which the EPA is now contesting.

The Boulder case will test how the Court views the EPA’s policy reversal long before legal challenges to the Trump administration get a hearing. SCOTUSblog reports that the Supreme Court is likely to hear oral arguments in the case, known as Suncor Energy Inc. v. County Commissioners of Boulder County, as soon as this fall. While the Boulder case contains similar public nuisance allegations to the American Electric Power case, Boulder brought them under state law, which means the legal questions and implications will be slightly different.

As for the possibility of a “patchwork of state regulations,” that’s a long ways away, if it is even possible at all, Alex said.

If the Supreme Court agrees with the EPA that the Clean Air Act does not apply to greenhouse gases, then there’s an argument that states are not precluded from acting, he told me. But there’s a counter-argument that any state action to regulate tailpipe greenhouse gas emissions will necessarily impact tailpipe emissions of other pollutants, bleeding into areas where Congress has explicitly preempted states from operating. “That’s also a good argument,” Alex said. “So it’s not clear to me how that would come out.”

Regardless, if the EPA’s final rule makes it through the highest court — which, to be sure, is not a foregone conclusion — Alex had no question that states would try to act. They will still have to meet the Clean Air Act’s general limits on air pollution, and California, for instance, “cannot meet those requirements without mobile source control,” he said. “They’ve got no choice but to seek regulations.”

The Northeast is in the middle of its first true blizzard in years. That long gap wasn’t because of climate change, though.

Happy blizzard day, Northeast. While you might be (okay, or most definitely are) sick of the snow at this point, take comfort in the fact that this storm is different. It meets the definition of a true blizzard, in which a large amount of snow falls with sustained winds over 35 miles per hour and visibility reduced to less than a quarter of a mile for more than three hours. That’s a mouthful, all of which is to say: Complain away! You’ve earned it!

New York City hasn’t issued a true blizzard warning since 2017 — but that isn’t because of climate change. In fact, big, bad storms like this one might be getting even worse.

I spoke with Colin Zarzycki, an associate professor of Meteorology and Climate Dynamics at Pennsylvania State University, on Monday morning about what we can expect from winter storms in a warming climate. Our conversation has been lightly edited for clarity, and the snow-weary should proceed with caution.

I've read both that blizzards will increase in a warming world because the atmosphere can hold more moisture to make more snow, and also that, because it’s warmer, a lot of the precipitation will fall as rain instead of snow, so the storms will decrease. What does the research actually say?

Let’s back up for one second. Blizzards like we have in the Northeast today are a subset of nor’easters. We also call them mid-latitude or extra-tropical cyclones — you hear people talk about “low pressure,” “bomb cyclones.” At the end of the day, these are synonyms for storms that track up the East Coast of the U.S. and dump a lot of snow, particularly along the major metro corridor.

A blizzard is a special subset, where you have strong winds that blow the snow around. And that’s really problematic, because — have you experienced a lot of snowstorms?

I went to college in Vermont and lived in New York City for 10 years, so I’m familiar with snow.

I ask because, every once in a while, you talk to someone from, like, Miami, and they’re like, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” But during these strong wind events, blowing snow reduces the visibility. That’s very bad for transportation like aviation, but also just driving on highways and roads.

I want to be careful, because there’s been less work done on the wind side of things. The broad consensus is that if you measure nor'easters as a function of their low pressure — which is somewhat analogous to wind speed; they’re not exactly related, but they’re pretty close — there actually doesn’t seem to be a huge shift. For every storm that comes up the East Coast and turns into a bomb that’s blowing 80-mile-an-hour winds, the distribution of the wind looks pretty similar across different climates, whether cooler or warmer.

What you’re referring to about the precipitation: — this is the thing we’re most confident in the science [of]. If you make the very simple argument — which admittedly, our models indicate it is not a bad argument — that if the number of nor’easters that move up the coast stays relatively constant and the intensity of them doesn’t change a lot as measured by wind speed, but if the atmosphere is warmer and can hold more water vapor, then the rates of what’s coming out of the sky essentially increase.

Now if you’re thinking, “Okay, well, that’s snow,” then yes. If you could take this storm and put it in a time machine and move it 50 years from now, and if the atmosphere is 2 degrees [Celsius] warmer, then you’re going to have more precipitation coming out of the sky, all other things being equal.

But you mentioned the other tricky thing that complicates life. When climate scientists think about precipitation in, let’s say, Florida, where it doesn’t snow at all, it generally all just goes one way: It gets warmer, it rains harder. But in the Northeast, we have two things that compete with each other. On the one hand, precipitation increases, as we just discussed. But then obviously, if it warms, more of these storms are likely to produce rain rather than snow.

If you look at just the average number of snowstorms in a warmer world, whether you’re comparing today relative to 1850, or if you’re looking at today and trying to figure out what’s going to happen in 2100, in general, the warmer it gets, the less total snow and the less total number of snowstorms because more of them become rainstorms. The tricky thing is, the decrease really only happens with the weaker snowstorms, the nuisance types.

So if we still get periods in warmer climates where it’s cold enough to snow, and now we’ve turbocharged the atmosphere’s ability to hold moisture by warming, then what we’ve actually done is make it so that when it does snow, it snows harder. In general, we expect to see fewer overall snowstorms when it’s warming, which is very consistent with what we’ve seen in observations in the Northeast U.S. If you look at any major metro area and you plot snow since 1950 it’s generally been on a downslope. But these big blizzard-type storms aren’t going away.

The jury is out as to whether the most, most, most, most extreme snowstorms become a little more extreme. But the big take-home message is that the frequency of big nor’easters isn’t going away, even if the climate warms.

There has been a lot of talk about this being the first blizzard to hit New York City in nine years. I don’t think I can remember a storm quite like this from when I was living there. Is that because this is the most extreme version you’re referring to, that we haven’t seen as often?

If you were to ask someone who has lived in New York City since the 1950s, they would probably tell you that this is a bad snowstorm, but that they’ve seen similar ones. I’m not an expert on the history of New York City weather, but there were a couple of big storms, I think, in the 1970s that were analogous to this, if not a little worse.

What is unique about this storm is that we really haven’t seen one of these tight coastal blizzards this year. We had that storm that came through earlier this year, which also brought a decent amount of snow to New York, but it tracked across the country rather than forming right off the coast and moving up that direction. This one is dragging snow across New York City and Boston; it’s a very classic Northeastern U.S. blizzard.

I think the main aspect is that we have been in a period of luck. We haven’t had these storms as frequently in the past. Some of it goes to that kind of dice-rolling thing with the temperatures. But if you look over the last 10 years, I would assume it’s not that New York City has been nice and sunny and calm in the winter. It’s that you’ve had these wintertime cyclones, but it’s been a lot more rain, or wet, rainy, sleety snow. It hasn’t been cold enough air to really lock in the blizzard conditions.

My understanding is that blizzards are specific atmospheric events in which the wind speed must exceed 35 miles per hour and visibility is limited. How difficult is that to capture in the data? I know from my reporting on tornadoes that it can be really difficult to capture wind events. How do you study this?

The fancy word in climate science is “compound extremes,” and a blizzard is a form of a compound extreme where you have multiple hazards at the same time. Add one layer on top of another, and the more there are, the harder it is to get information out of the data.

Especially in densely populated areas like the Northeastern U.S., blizzards are fairly tricky to look at. When you read the National Weather Service’s definition of a blizzard, it’s like, “It has to be snowing, and you have to have sustained winds, and you have to have decreased visibility.” All of those mean you’re adding layers of complexity to the data.

Tornadoes are a little similar; they’re a discrete phenomenon, and you need specific ingredients to all line up, and there’s also an observation problem. It’s somewhat analogous to blizzards: I could be at JFK Airport in New York, which is right on the ocean. There’s not a lot in the way to slow down the winds. Especially if you have drier snow, it’s very easy for it all to blow around. If I’m a guy working at JFK, I’m saying, “This is really bad, it’s really windy, the snow is coming down, and we can’t see anything. We have to shut everything down.” But put yourself in Midtown or somewhere where you’re surrounded by buildings and a little further away from the ocean, then suddenly the winds might be reduced because you have more obstacles that can slow it down. You’re experiencing the exact same storm, but the impacts are very different.

You said at the beginning that the underlying assumption is that nor’easters will continue at the same rate they’re happening now. Is there anything I should know about the way climate change is impacting those events?

Precipitation is the main thing. There’s been some work on the frequency and track of the storms, and we’ve seen small changes. But we also have a sample-size problem. The more you want to focus on the intense storms, the less you have in your records, and the more challenging it is to tease out what’s going on. That’s one of the reasons I really like models.

So maybe, if you squint, you can see some small changes in the frequency or the track, but it’s on the order of 5% to 10% per year. But the number of nor’easters we actually get in a given winter is not small; depending on how you want to classify it, it’s something like 10 to 15 any given winter. They don’t all produce a lot of snow; some of them go offshore, and if you’re sailing a boat in the middle of the ocean, then you’d be like, yeah, this is a big problem. But generally, we have very high confidence in understanding the precipitation, and decent confidence in understanding how the rain-snow partitioning changes. The winds, I think, are kind of an open question. But we’re talking secondary effects relative to the precipitation for all of them.

Is there anything else I should know about blizzards and climate change?

I do interviews every winter about bomb cyclones and big storms. The fact that I do multiple interviews a winter implies that the storms themselves are not anomalous. If you actually count them, you end up with a decent number. You just need the dice to come up snake eyes — all the ingredients need to line up for it to be something impactful. And that’s what’s happening now.

What climate change does is change the underlying probabilities and distributions. But at the end of the day, the main thing that actually drives what’s going on with these storms is, can the atmosphere put the Lego pieces together for these impacts? Every cyclone that we get during the winter, if you go back and look at the historical record, there’s plenty of evidence for these types of storms.

On the California atom, Russian nuclear theft, and Taiwan’s geothermal hope

Current conditions: A blockbuster blizzard blanketed the Northeast in up to 2 feet of snow, trigger outages for nearly 500,000 households • Hot, dry Harmattan conditions are blowing into Nigeria out of the Sahara, leaving the capital, Abuja, and the largest city, Lagos, roasting in nearly 100 degrees Fahrenheit • Much of South Australia, the Northern Territory, and Victoria are bracing for severe thunderstorms and flooding.

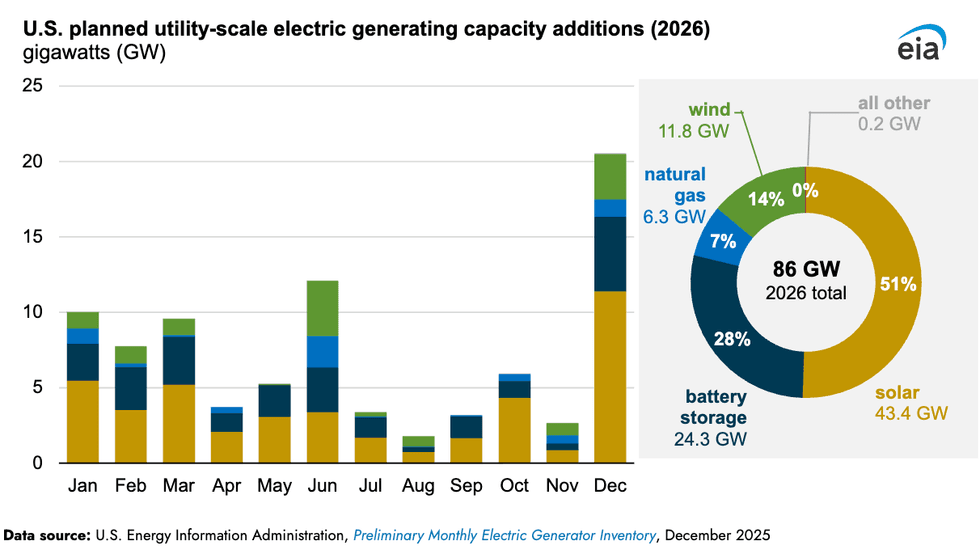

By the end of this year, U.S. developers are on pace to add 86 gigawatts of new utility-scale generating capacity to the American grid. Just 7% of that will come from natural gas. The other 93%? Solar, batteries, and wind, according to the latest inventory by the Energy Information Administration. Utility-scale solar projects alone will provide 51% of the new generating capacity, followed by batteries at 28%, and wind at 14%. Critics of renewables, such as Secretary of Energy Chris Wright, would point out that generating capacity does not equal generation, and that as has happened recently, gas, coal, and nuclear power may well end up pumping out a lot of the electricity this year. But rapid expansion of renewables and batteries comes largely despite the Trump administration’s efforts to curb the growth of what top officials dismiss as “unreliable” sources of power. Surging electricity demand from data centers has left gas turbines backordered; geothermal plants are still at an early stage; and new nuclear reactors are still years away. That makes solar and wind, already some of the cheapest sources to build, the only obvious options to bring new generation online as quickly as possible. In a sense, Trump may have helped nudge 2026’s boom into existence by phasing off federal tax credits for renewables this year, spurring a rush to get projects started and lock in the writeoffs.

That doesn’t mean the solar, battery, and wind sectors aren’t facing steep challenges. Just last week, Heatmap’s Jael Holzman rounded up four local fights on opposite coasts, including over a big solar farm in Oregon.

California could consider building anything from a large-scale Westinghouse AP1000 to a next-generation microreactor if a new bill to clarify the state’s ban on new nuclear power plants passes into law. On Friday, Assemblymember Lisa Calderon, a Democrat from Southern California, introduced AB2647 to modify the state moratorium put in place in 1976, three years before the Three Mile Island accident, to allow for construction of modern nuclear reactors. The legislation would exempt all reactor designs certified by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission after January 1, 2005. That clears the way for an AP1000, which was approved in 2006, and today is the only new design in commercial operation in the U.S., or any of the new small modular reactors and microreactors now racing to come to market. The bill is bringing together disparate factions in the California legislature. Progressive Assemblymember Alex Lee co-sponsored the legislation, while Senator Brian Jones, the highest ranking Republican in the state’s upper chamber, is backing a Senate version of the legislation.

Since Friday, I can report exclusively in this newsletter, the bill has two new supporters. Patrick Ahrens, a Silicon Valley-area Democrat, has signed on as a backer, and the Sheet Metal Workers union has said it would support the bill. “Pinching myself,” Ryan Pickering — a reactor developer and Berkeley-based activist who helped lead the successful campaign to cancel the closure of the state’s last plant, the Diablo Canyon nuclear station — responded when I texted him to ask about the bill. “California has an epic history in nuclear energy. We built 11 reactors across this state and once envisioned up to 14 gigawatts of nuclear electricity. This technology is part of our inheritance as Californians,” he said. “Assembly Bill 2647 gives California the opportunity to begin building nuclear energy again.”

If you have ever crossed the Queensboro Bridge from Manhattan’s 59th Street over to Long Island City in Queens, you have no doubt seen the Ravenswood Generating Station. The four candycane-colored smokestacks of New York City’s largest power plant, a more than 2-gigawatt facility equipped to burn both fuel oil and natural gas, rise on the lefthand side of the bridge, looming over the East River. Just a few years ago, its owner, LS Power, envisioned transforming the plant through a subsidiary called Rise Light and Power, which aimed to build a large-scale battery hub fed by new transmission lines connecting the facility to nearby offshore wind farms and onshore turbines upstate. Now, as Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo reported in a Friday scoop, the company is selling Ravenswood to the Texas energy giant NRG. It’s not yet clear what the sale means for the so-called Renewable Ravenswood plan, which Emily wrote was already “hanging by a thread.”

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Since the start of its invasion of Ukraine, Russia has maintained clear designs on the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant. Europe’s largest atomic generating station, located in an occupied province of eastern Ukraine, has been offline for the past four years. But, in a bid to shore up on the Kremlin’s desired war prizes as peace negotiations sputter, Russia’s nuclear regulator Rostekhnadzor has issued a 10-year operating license for Unit 2 of the plant. In its announcement, NucNet reported Friday, Rostekhnadzor said the move would open the door to building more Russian nuclear plants in the region. Rosatom, Moscow’s state-owned nuclear company, has submitted an application for an operating license for Unit 6, and aims to do the same for units 3, 4, and 5 by the end of this year.

The neighboring country most eager to contain Russia, meanwhile, took a big step toward building its first nuclear plant. The Supreme Administrative Court in Poland, whose debut facility is going with American technology, rejected an environmental complaint aimed at halting construction of AP1000 reactors at the site on the Baltic sea.

Earlier this month, I told you about Equinor’s plans to scale back its investments in carbon capture and sequestration, despite Norway’s world-leading progress on pumping captured CO2 back underground. Now the Norwegian energy giant is quitting on one of the European Union’s landmark projects to prove hydrogen fuel can be produced at scale using natural gas equipped with CCS. The company last week abandoned a gigawatt-sized blue hydrogen plant in the Netherlands as demand for the fuel stalls. Some may welcome the blue hydrogen recession. As Heatmap’s Katie Brigham wrote last year, a major blue hydrogen plant in Louisiana had been poised to add more emissions than it saved.

Things are looking sunnier in South America for green hydrogen, the carbon-free version of the fuel made from blasting freshwater with enough renewable electricity to separate out H from H2O. Colombia just completed a feasibility study on the country’s first industrial-scale green hydrogen project, set to generate 120,000 metric tons of green ammonia per year at a remarkably low price, according to Hydrogen Insight. At the opposite end of the continent, Uruguay’s 1.1-gigawatt green hydrogen-fueled methanol plant last week lined up a major offtaker that plans to buy the chemical to make lower-carbon gasoline. The purchaser? A fuel company based in a major artery of European trade, Germany’s Port of Hamburg.

Taiwan is in an energy crisis. The self-governing island, whose “silicon shield” against China is predicated on its capacity to manufacture enough energy-intensive semiconductors to be invaluable to the global economy, shut down its last nuclear reactor last year. By exiting atomic energy while struggling to build offshore wind turbines, the government in Taipei has rendered Taiwan almost entirely dependent on imported fuels. In an age when, as Russia has shown in Ukraine, blackouts are key weapons, the People’s Liberation Army need only make liquified natural gas dangerous to ship through the Taiwan Strait to cause blackouts. But geothermal power, development of which stalled out after the 1970s, offers a unique tool for Taiwan. Located on the Pacific Rim, the island has lots of hot rocks. Now it finally has a growing geothermal industry again, too. The CPC Corporation Taiwan said just before Lunar New Year started last week that it had just started generating power from the 5.4-megawatt Yilan Tuchang Geothermal plant. While small, it’s now the largest geothermal plant in Taiwan.