You’re out of free articles.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Sign In or Create an Account.

By continuing, you agree to the Terms of Service and acknowledge our Privacy Policy

Welcome to Heatmap

Thank you for registering with Heatmap. Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of our lives, a force reshaping our economy, our politics, and our culture. We hope to be your trusted, friendly, and insightful guide to that transformation. Please enjoy your free articles. You can check your profile here .

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Subscribe to get unlimited Access

Hey, you are out of free articles but you are only a few clicks away from full access. Subscribe below and take advantage of our introductory offer.

subscribe to get Unlimited access

Offer for a Heatmap News Unlimited Access subscription; please note that your subscription will renew automatically unless you cancel prior to renewal. Cancellation takes effect at the end of your current billing period. We will let you know in advance of any price changes. Taxes may apply. Offer terms are subject to change.

Create Your Account

Please Enter Your Password

Forgot your password?

Please enter the email address you use for your account so we can send you a link to reset your password:

With the ongoing disaster approaching its second week, here’s where things stand.

A week ago, forecasters in Southern California warned residents of Los Angeles that conditions would be dry, windy, and conducive to wildfires. How bad things have gotten, though, has taken everyone by surprise. As of Monday morning, almost 40,000 acres of Los Angeles County have burned in six separate fires, the biggest of which, Palisades and Eaton, have yet to be fully contained. The latest red flag warning, indicating fire weather, won’t expire until Wednesday.

Many have questions about how the second-biggest city in the country is facing such unbelievable devastation (some of these questions, perhaps, being more politically motivated than others). Below, we’ve tried to collect as many answers as possible — including a bit of good news about what lies ahead.

A second Santa Ana wind event is due to set in Monday afternoon. “We’re expecting moderate Santa Ana winds over the next few days, generally in the 20 to 30 [mile per hour] range, gusting to 50, across the mountains and through the canyons,” Eric Drewitz, a meteorologist with the Forest Service, told me on Sunday. Drewitz noted that the winds will be less severe than last week’s, when the fires flared up, but he also anticipates they’ll be “more easterly,” which could blow the fires into new areas. A new red flag warning has been issued through Wednesday, signaling increased fire potential due to low humidity and high winds for several days yet.

If firefighters can prevent new flare-ups and hold back the fires through that wind event, they might be in good shape. By Friday of this week, “it looks like we could have some moderate onshore flow,” Drewitz said, when wet ocean air blows inland, which would help “build back the marine layer” and increase the relative humidity in the region, decreasing the chances of more fires. Information about the Santa Anas at that time is still uncertain — the models have been changing, and the wind is tricky to predict the strength of so far out — but an increase in humidity will at least offer some relief for the battered Ventura and Orange Counties.

The Palisades Fire, the biggest in L.A., ripped through the hilly and affluent area between Santa Monica and Malibu, including the Pacific Palisades neighborhood, the second-most expensive zip code in Los Angeles and home to many celebrities. Structures in Big Rock, a neighborhood in Malibu, have also burned. The fire has also encroached on the I-405 and the Getty Villa, and destroyed at least two homes in Mandeville Canyon, a neighborhood of multimillion-dollar homes. Students at nearby University of California, Los Angeles, were told on Friday to prepare for a possible evacuation.

The Eaton Fire, the second biggest blaze in the area, has killed 16 people in Altadena, a neighborhood near Pasadena, according to the Los Angeles Times, making it one of the deadliest fires in the modern history of California.

The 1,000-acre Kenneth fire is 100% contained but still burning near Calabasas and the gated community of Hidden Hills. The Hurst Fire has burned nearly 800 acres and is 89% contained and is still burning near Sylmar, the northernmost neighborhood in L.A. Though there are no evacuation notices for either the Kenneth or the Hurst fires, residents in the L.A. area should monitor the current conditions as the situation continues to be fluid and develop.

The 43-acre Sunset Fire, which triggered evacuations last week in Hollywood and Hollywood Hills, burned no homes and is 100% contained.

The Lidia Fire, which ignited in a remote area south of Acton, California, on Wednesday afternoon, burned 350 acres of brush and is 100% contained.

It can take years to determine the cause of a fire, and investigations typically don’t begin until after the fire is under control and the area is safe to reenter, Edward Nordskog, a retired fire investigator from the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department, told Heatmap’s Emily Pontecorvo. He also noted, however, that urban fires are typically easier to pinpoint the cause of than wildland fires due to the availability of witnesses and surveillance footage.

The vast majority of wildfires, 85%, are caused by humans. So far, investigators have ruled out lightning — another common fire-starter — because there were no electrical storms in the area when the fires started. In the case of the Palisades Fire, there were no power lines in the area of the ignition, though investigators are now looking into an electrical transmission tower in Eaton Canyon as the possible cause of the deadly fire in Altadena. There have been rumors that arsonists started the fires, but investigators say that scenario is also pretty unlikely due to the spread of the fires and how remote the ignition areas are.

Officially, 24 people have died, but that tally is likely to rise. California Governor Gavin Newsom said Sunday that he expects “a lot more” deaths will be added to the total in the coming days as search efforts continue.

Incoming President Donald Trump slammed the response to the L.A. fires in a Truth Social post on Sunday morning: “This is one of the worst catastrophes in the history of our Country,” he wrote. “They just can’t put out the fires. What’s wrong with them?”

Though there is much blame going around — not all of it founded in reality — the challenges facing firefighters are immense. Last week, because of strong Santa Ana winds, fire crews could not drop suppressants like water or chemical retardant on the initial blazes. (In strong winds, water and retardant will blow away before they reach the flames on the ground.)

Fighting a fire in an urban or suburban area is also different from fighting one in a remote, wild area. In a true wildfire, crews don’t use much water; firefighters typically contain the blazes by creating breaks — areas cleared of vegetation that starve a fire of fuel and keep it from spreading. In an urban or suburban event, however, firefighters can’t simply hack through a neighborhood, and typically have to use water to fight structure fires. Their priority also shifts from stopping the fire to evacuating and saving people, which means putting out the fire itself has to wait.

What’s more, the L.A. area faced dangerous fire weather going into last week — with wind gusts up to 100 miles per hour and dry air — and the persistence of the Santa Ana winds during firefighting operations through the weekend made it extremely difficult for emergency managers to gain a foothold.

Trump and others have criticized Los Angeles for being unprepared for the fires, given reports that some fire hydrants ran dry or had low pressure during operations in Pacific Palisades. According to the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, about 20% of hydrants were affected, mostly at higher elevations.

The problem isn’t a lack of preparation, however. It’s that the L.A. wildfires are so large and widespread, the county’s preparations were quickly overwhelmed. “We’re fighting a wildfire with urban water systems, and that is really challenging,” Los Angeles Department of Water and Power CEO Janisse Quiñones said in a news conference last week. When houses burn down, water mains can break open. Civilians also put a strain on the system when they use hoses or sprinkler systems to try to protect their homes.

On Sunday, Judy Chu, the Democratic lawmaker representing Altadena, confirmed that fire officials had told her there was enough water to continue the battle in the days ahead. “I believe that we're in a good place right now,” she told reporters. Newsom, meanwhile, has responded to criticism over the water failure by ordering an investigation into the weak or dry hydrants.

So-called “super soaker” planes have had no problem with water access; they’re scooping directly from the ocean.

Yes. Although aerial support was grounded in the early stages of the wildfires due to severe Santa Ana winds, flights resumed during lulls in the storms last week.

There is a misconception, though, that water and retardant drops “put out” fires; they don’t. Instead, aerial support suppresses a fire so crews can get in close and use traditional methods, like cutting a fire break or spraying water. “All that up in the air, all that’s doing is allowing the firefighters [on the ground] a chance to get in,” Bobbie Scopa, a veteran firefighter and author of the memoir Both Sides of the Fire Line, told me last week.

With winds expected to pick up early this week, aerial firefighting operations may be grounded again. “If you have erratic, unpredictable winds to where you’ve got a gust spread of like 20 to 30 knots,” i.e. 23 to 35 miles per hour, “that becomes dangerous,” Dan Reese, a veteran firefighter and the founder and president of the International Wildfire Consulting Group, told me on Friday.

Because of the direction of the Santa Ana winds, wildfire smoke should mostly blow out to sea. But as winds shift, unhealthy air can blow into populated areas, affecting the health of residents.

Wildfire smoke is unhealthy, period, but urban and suburban smoke like that from the L.A. fires can be particularly detrimental. It’s not just trees and brush immolating in an urban fire, it’s also cars, and batteries, and gas tanks, and plastics, and insulation, and other nasty, chemical-filled things catching fire and sending fumes into the air. PM2.5, the inhalable particulates from wildfire smoke, contributes to thousands of excess deaths annually in the U.S.

You can read Heatmap’s guide to staying safe during extreme smoke events here.

“The bad news is, I’m not seeing any rain chances,” Drewitz, the Forest Service meteorologist, told me on Sunday. Though the marine layer will bring wetter air to the Los Angeles area on Friday, his models showed it’ll be unlikely to form precipitation.

Though some forecasters have signaled potential rain at the end of next week, the general consensus is that the odds for that are low, and that any rain there may be will be too light or short-lived to contribute meaningfully to extinguishing the fires.

The chaparral shrublands around Los Angeles are supposed to burn every 30 to 130 years. “There are high concentrations of terpenes — very flammable oils — in that vegetation; it’s made to burn,” Scopa, the veteran firefighter, told me.

What isn’t normal, though, is the amount of rain Los Angeles got ahead of this past spring — 52.46 inches in the preceding two years, the wettest period in the city’s history since the late 1800s — which was followed by a blisteringly hot summer and a delayed start to this year’s rainy season. Since October, parts of Southern California have received just 10% of their normal rainfall

This “weather whiplash” is caused by a warmer atmosphere, which means that plants will grow explosively due to the influx of rain and then dry out when the drought returns, leaving lots of dry fuels ready and waiting for a spark. “This is really, I would argue, a signature of climate change that is going to be experienced almost everywhere people actually live on Earth,” Daniel Swain, a climate scientist at the University of California, Los Angeles, who authored a new study on the pattern, told The Washington Post.

We know less about how climate change may affect the Santa Anas, though experts have some theories.

At least 12,000 structures have burned so far in the fires, which is already exacerbating the strain on the Los Angeles housing market — one of the country’s tightest even before the fires — as thousands of displaced people look for new places to live. “Dozens and dozens of people are going after the same properties,” one real estate agent told the Los Angeles Times. The city has reminded businesses that price gouging — including raising rental prices more than 10% — during an emergency is against the law.

Los Angeles had a shortage of about 370,000 homes before the fires, and between 2021 and 2023, the county added fewer than 30,000 new units per year. Recovery grants and federal aid can lag, and it often takes more than two years for even the first Housing and Urban Development Disaster Recovery Grants’ expenditures to go out.

My colleague Matthew Zeitlin wrote for Heatmap that the economic impact of the Los Angeles fire is already much higher than that of other fires, such as the 2018 Camp fire, partly because of the value of the Pacific Palisades real estate.

The wildfires may “deal a devastating blow to [California’s] fragile home insurance market,” Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote last week. In recent years, home insurers have left California or declined to write new policies, at least partially due to the increased risk of wildfires in the state.

Depending on the extent of the damage from the fires, the coffers of California’s FAIR Plan — which insures homeowners who can’t get insurance otherwise, including many in Pacific Palisades and Altadena — could empty, causing it to seek money from insurers, according to the state’s regulations. As Zeitlin writes, “This would mean that Californians who were able to buy private insurance — because they don’t live in a region of the state that insurers have abandoned — could be on the hook for massive wildfire losses.”

First and foremost, sign up for all relevant emergency alerts. Make sure to turn on the sound on your phone and keep it near you in case of a change in conditions. Pack a “go bag” with essentials and consider filling your gas tank now so that you can evacuate at a moment’s notice if needed. Read our guide on what to do if you get a pre-evacuation or an evacuation notice ahead of time so that you’re not scrambling for information if you get an alert.

The free Watch Duty app has become a go-to resource for people affected by the fires, including friends and family of Angelenos who may themselves be thousands of miles away. The app provides information on fire perimeters, evacuation notices, and power outages. Its employees pull information directly from emergency responders’ radio broadcasts and sometimes beat official sources to disseminating it. If you need an endorsement: Emergency responders rely on the app, too.

There are many scams in the wake of disasters as crooks look to take advantage of desperate people — and those who want to help them. To play it safe, you can use a hub like the one established by GoFundMe, which is actively vetting campaigns related to the L.A. fires. If you’re looking to volunteer your time, make a donation of clothing or food, or if you’re able to foster animals the fire has displaced, you can use this handy database from the Mutual Aid Network L.A. There are also many national organizations, such as the Red Cross, that you can connect with if you want to help.

The City of Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Fire Department have asked that do-gooders not bring donations directly to fire stations or shelters; such actions can interfere with emergency operations. Their website provides more information about how you can help — productively — on their website.

Log in

To continue reading, log in to your account.

Create a Free Account

To unlock more free articles, please create a free account.

Boosters say that the energy demand from data centers make VPPs a necessary tool, but big challenges still remain.

The story of electricity in the modern economy is one of large, centralized generation sources — fossil-fuel power plants, solar farms, nuclear reactors, and the like. But devices in our homes, yards, and driveways — from smart thermostats to electric vehicles and air-source heat pumps — can also act as mini-power plants or adjust a home’s energy usage in real time. Link thousands of these resources together to respond to spikes in energy demand or shift electricity load to off-peak hours, and you’ve got what the industry calls a virtual power plant, or VPP.

The theoretical potential of VPPs to maximize the use of existing energy infrastructure — thereby reducing the need to build additional poles, wires, and power plants — has long been recognized. But there are significant coordination challenges between equipment manufacturers, software platforms, and grid operators that have made them both impractical and impracticable. Electricity markets weren’t designed for individual consumers to function as localized power producers. The VPP model also often conflicts with utility incentives that favor infrastructure investments. And some say it would be simpler and more equitable for utilities to build their own battery storage systems to serve the grid directly.

Now, however, many experts say that VPPs’ time to shine is nigh. Homeowners are increasingly pairing rooftop solar with home batteries, installing electric heat pumps, and buying EVs — effectively large batteries on wheels. At the same time, the ongoing data center buildout has pushed electricity demand growth upward for the first time in decades, leaving the industry hungry for new sources of cheap, clean, and quickly deployable power.

“VPPs have been waiting for a crisis and cash to scale and meet the moment. And now we have both,” Mark Dyson, a managing director at RMI, a clean energy think tank, told me. “We have a load growth crisis, and we have a class of customers who have a very high willingness to pay for power as quickly as possible.” Those customers are the data center hyperscalers, of course, who are impatient to circumvent the lengthy grid interconnection queue in any way possible, potentially even by subsidizing VPP programs themselves.

Jigar Shah, former director of the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office under President Biden, is a major VPP booster, calling their scale-up “the fastest and most cost-effective way to support electrification” in a 2024 DOE release announcing a partnership to integrate VPPs onto the electric grid. While VPPs today provide roughly 37.5 gigawatts of flexible capacity, Shah’s goal was to scale that to between 80 and160 gigawatts by 2030. That’s equivalent to around 7% to 13% of the U.S.’s current utility-scale electricity generating capacity.

Utilities are infamously slow to adopt new technologies. But Apoorv Bhargava, CEO and co-founder of the utility-focused VPP software platform WeaveGrid, told me that he’s “felt a sea change in how aware utilities are that, building my way out is not going to happen; burning my way out is not going to happen.” That’s led, he explained, to an industry-wide recognition that “we need to get much better at flexing resources — whether that’s consumer resources, whether that’s utility-sited resources, whether that’s hyperscalers even. We’ve got to flex.”

Actual VPP capacity appears to have grown more slowly over the past few years than the enthusiasm surrounding the resource’s potential. According to renewable energy consultancy WoodMackenzie, while the number of new VPP programs, offtakers, and company deployments each grew over 33% last year, capacity grew by a more modest 13.7%. Ben Hertz-Shargel, who leads a WoodMac research team focused on distributed energy resources, attributed this slower growth to utility pilot programs that cap VPP participation, rules that limit financial incentives by restricting how VPP capacity is credited, and other market barriers that make it difficult for customers to engage.

Dyson similarly said he sees “friction on the utility side, on the regulatory side, to align the incentive programs with real needs.” These points of friction include requirements for all participating devices to communicate real-time performance data — even for minor, easily modeled metrics such as a smart thermostat’s output — as well as utilities’ hesitancy to share household-level metering data with third parties, even when it’s necessary to enroll in a VPP program. Figuring out new norms for utilities and state regulations is “the nut that we have to crack,” he said.

One of the more befuddling aspects of the whole VPP ecosystem, however, can be just trying to parse out what services a VPP program can actually provide. The term VPP can refer to anything from decades-old demand response programs that have customers manually shutting off appliances during periods of grid stress to aspirational, fully integrated systems that continually and automatically respond to the grid’s needs.

“When a customer like a utility says, I want to do a VPP, nobody knows what they’re talking about. And when a regulator says we should enable VPPs, nobody knows what services they’re selling,” Bhargava told me.

In an effort to help clarify things, the software company EnergyHub developed what it calls the VPP Maturity Model, which defines five levels of maturity. Level 0 represents basic demand response. A utility might call up an industrial customer and tell them to reduce their load, or use price signals to encourage households to cut down on electricity use in the evening. Level 1 incorporates smart devices that can send data back to the utility, while at Level 2, VPPs can more precisely ramp load up or down over a period of hours with better monitoring, forecasting, and some partial autonomy — this is where most advanced VPPs are at today.

Moving into Levels 3 and 4 involves more automation, the ability to handle extended grid events, and ultimately full integration with the utility and grid-operator’s systems to provide 24/7 value. The ultimate goal, according to EnergyHub’s model, is for VPPs to operate indistinguishably from conventional power plants, eventually surpassing them in capabilities.

But some question whether imitating such a fundamentally different resource should actually be the end game.

“What we don’t need is a bunch of virtual power plants that are overconstrained to act just like gas plants,” Dyson told me. By trying to engineer “a new technology to behave like an old technology,” he said, grid operators risk overlooking the unique value VPPs can provide — particularly on the distribution grid, which delivers electricity directly to homes and businesses. Here, VPPs can help manage voltage regulation or work to avoid overloads on lines with many distributed resources, such as solar panels — things traditional power plants can’t do because they’re not connected to these local lines.

Still others are frankly dubious of the value of large-scale VPP programs in the first place. “The benefits of virtual power plants, they look really tantalizing on paper,” Ryan Hanna, a research scientist at UC San Diego’s Center for Energy Research told me. “Ultimately, they’re providing electric services to the electric power grid that the power grid needs. But other resources could equally provide those.”

Why not, he posited, just incentivize or require utilities to incorporate battery storage systems at either the transmission or distribution levels into their long-term plans for meeting demand? Large-scale batteries would also help utilities maximize the value of their existing assets and capture many of the other benefits VPPs promise. Plus, they would do it at a “larger size, and therefore a lower unit cost,” Hanna told me.

Many VPP companies would certainly dispute the cost argument, and also note that with grid interconnection queues stretching on for years, VPPs offer a way to deploy aggregated resources far more quickly than building out and connecting new, centralized assets.

But another advantage of Hanna’s utility-led approach, he said, is that the benefits would be shared equally — all customers would see similar savings on their electricity bills as grid-scale batteries mitigate the need for expensive new infrastructure, the cost of which is typically passed on to ratepayers. VPPs, on the other hand, deliver an outsize benefit to the customers incentivized to participate by dint of their neighborhood’s specific needs, and with the cash on hand to invest in resources such as a home battery or an EV.

This echoes a familiar equity argument made about rooftop solar: that the financial benefits accrue only to households that can afford the upfront investment, while the cost of maintaining shared grid infrastructure falls more heavily on non-participants. Except in the case of VPPs, non-participants also stand to benefit — just less — if the programs succeed in driving down system costs and improving grid reliability.

“I may pay Customer A and Customer B may sit on the sidelines,” Matthew Plante, co-founder and president of the VPP operator Voltus, told me. “Customer A gets a direct payment, but customer B’s rates go down. And so everyone benefits, even if not directly.” On the flip side, if the VPP didn’t exist, that would be a lose-lose for all customers.

Plante is certainly not opposed to the idea of utilities building grid-scale batteries themselves, though. Neither he nor anyone else can afford to be picky about the way new capacity comes online right now, he said. “I think we all want to say, what is quickest and most efficient and most economical? And let’s choose that solution. Sometimes it’s got to be both.”

For its part, Voltus is betting that its pathway to scale runs through its recently announced partnership with the U.S. division of Octopus Energy, the U.K.’s largest energy supplier, which provides software to utilities to coordinate distributed energy resources and enroll customers in VPP programs. Together, they plan to build portfolios of flexible capacity for utilities and wholesale electricity markets, areas where Octopus has extensive experience. “So that gives us market access in a much quicker way,” Plante told me.”

At this moment, there’s no customer more motivated than a data center to bring large volumes of clean energy online as quickly as possible, in whatever way possible. Because while data enters themselves can theoretically act as flexible loads, ramping up and down in response to grid conditions, operators would probably rather pay others to be flexible instead.

“Does a data center company ever want to say, okay, I won’t run my training model for a couple hours on the hottest day of the year? They don’t, because it’s worth a lot of money to run that training model 24/7,” Dyson told me. “Instead, the opportunity here is to use the money that generates to pay other people to flex their load, or pay other people to adopt batteries or other resources that can help create headroom on the system.”

Both Plante of Voltus and Bhargava of WeaveGrid confirmed that hyperscalers are excited by the idea of subsidizing VPP programs in one form or another. That could look like providing capital to help customers in a data center’s service territory buy residential batteries or contracts that guarantee a return for VPP aggregators like Voltus. “I think they recognize in us an ability to get capacity unlocked quickly,” Plante told me.

Yet another knot in this whole equation, however, is that even given hyperscalers’ enthusiasm and the maturation of VPP technology, most utilities still lack a natural incentive to support this resource. That’s because investor-owned utilities — which serve approximately 70% of U.S. electricity customers — earn profits primarily by building infrastructure such as power plants and transmission lines, receiving a guaranteed rate of return on that capital investment. Successful VPPs, on the other hand, reduce a utility’s need to build new assets.

The industry is well aware of this fundamental disconnect, though some contend that current load growth ought to quell this concern. Utilities will still need to build significant new infrastructure to meet the moment, Bhargava told me, and are now under intense pressure to expand the grid’s capacity in other ways, as well.

“They cannot build fast enough. There’s not enough copper, there’s not enough transformers, there’s not enough people,” Bhargava explained. VPPs, he expects, will allow utilities to better prioritize infrastructure upgrades that stand to be most impactful, such as building a substation near a data center instead of in a suburb that could be adequately served by distributed resources.

The real question he sees now is, “How do we make our flexibility as good as copper? How do we make people trust in it as much as they would trust in upgrading the system?”

On the real copper gap, Illinois’ atomic mojo, and offshore headwinds

Current conditions: The deadliest avalanche in modern California history killed at least eight skiers near Lake Tahoe • Strong winds are raising the wildfire risk across vast swaths of the northern Plains, from Montana to the Dakotas, and the Southwest, especially New Mexico, Texas, and Oklahoma • Nairobi is bracing for days more of rain as the Kenyan capital battles severe flooding.

Last week, the Environmental Protection Agency repealed the “endangerment finding” that undergirds all federal greenhouse gas regulations, effectively eliminating the justification for curbs on carbon dioxide from tailpipes or smokestacks. That was great news for the nation’s shrinking fleet of coal-fired power plants. Now there’s even more help on the way from the Trump administration. The agency plans to curb rules on how much hazard pollutants, including mercury, coal plants are allowed to emit, The New York Times reported Wednesday, citing leaked internal documents. Senior EPA officials are reportedly expected to announce the regulatory change during a trip to Louisville, Kentucky on Friday. While coal plant owners will no doubt welcome less restrictive regulations, the effort may not do much to keep some of the nation’s dirtiest stations running. Despite the Trump administration’s orders to keep coal generators open past retirement, as Heatmap’s Matthew Zeitlin wrote in November, the plants keep breaking down.

At the same time, the blowback to the so-called climate killshot the EPA took by rescinding the endangerment finding has just begun. Environmental groups just filed a lawsuit challenging the agency’s interpretation of the Clean Air Act to cover only the effects of regional pollution, not global emissions, according to Landmark, a newsletter tracking climate litigation.

Copper prices — as readers of this newsletter are surely well aware — are booming as demand for the metal needed for virtually every electrical application skyrockets. Just last month, Amazon inked a deal with Rio Tinto to buy America’s first new copper output for its data center buildout. But new research from a leading mineral supply chain analyst suggests the U.S. can meet 145% of its annual demand using raw copper from overseas and domestic mines and from scrap. By contrast, China — the world’s largest consumer — can source just 40% of its copper that way. What the U.S. lacks, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, is the downstream processing capacity to turn raw copper into the copper cathode manufacturers need. “The U.S. is producing more copper than it uses, and is far more self-reliant than China in terms of raw materials,” Benchmark analyst Albert Mackenzie told the Financial Times. The research calls into question the Trump administration’s mineral policy, which includes stockpiling copper from jointly-owned ventures in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and domestically. “Stockpiling metal ores doesn’t help if you don’t have midstream processing,” Stephen Empedocles, chief executive of US lobbying firm Clark Street Associates, told the newspaper.

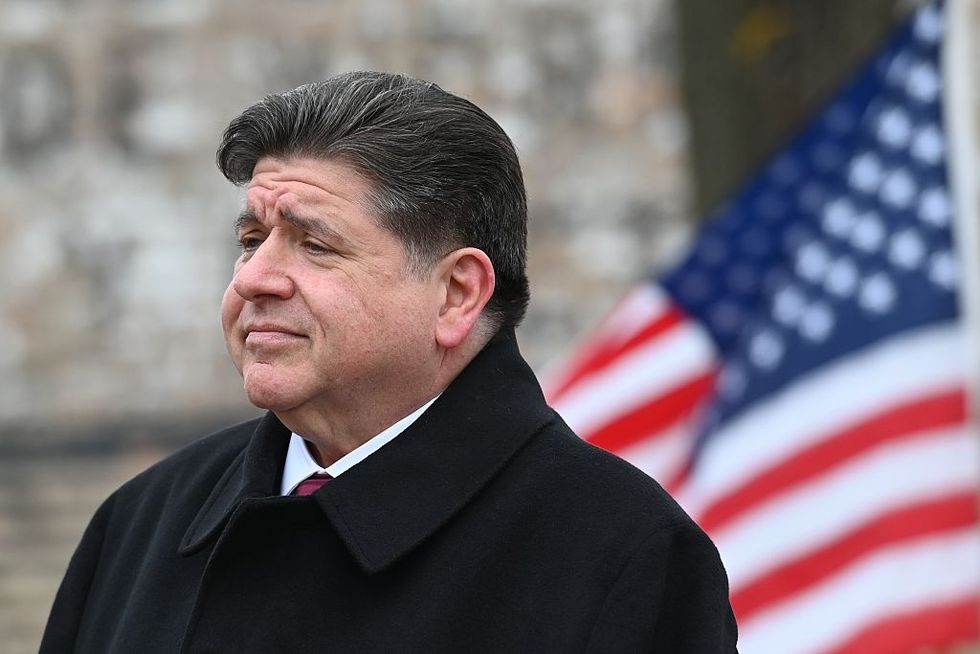

Illinois generates more of its power from nuclear energy than any other state. Yet for years the state has banned construction of new reactors. Governor JB Pritzker, a Democrat, partially lifted the prohibition in 2023, allowing for development of as-yet-nonexistent small modular reactors. With excitement about deploying large reactors with time-tested designs now building, Pritzker last month signed legislation fully repealing the ban. In his state of the state address on Wednesday, the governor listed the expansion of atomic energy among his administration’s top priorities. “Illinois is already No. 1 in clean nuclear energy production,” he said. “That is a leadership mantle that we must hold onto.” Shortly afterward, he issued an executive order directing state agencies to help speed up siting and construction of new reactors. Asked what he thought of the governor’s move, Emmet Penney, a native Chicagoan and nuclear expert at the right-leaning Foundation for American Innovation, told me the state’s nuclear lead is “an advantage that Pritzker wisely wants to maintain.” He pointed out that the policy change seems to be copying New York Governor Kathy Hochul’s playbook. “The governor’s nuclear leadership in the Land of Lincoln — first repealing the moratorium and now this Hochul-inspired executive order — signal that the nuclear renaissance is a new bipartisan commitment.”

The U.S. is even taking an interest in building nuclear reactors in the nation that, until 1946, was the nascent American empire’s largest overseas territory. The Philippines built an American-made nuclear reactor in the 1980s, but abandoned the single-reactor project on the Bataan peninsula after the Chernobyl accident and the fall of the Ferdinand Marcos dictatorship that considered the plant a key state project. For years now, there’s been a growing push in Manila to meet the country’s soaring electricity needs by restarting work on the plant or building new reactors. But Washington has largely ignored those efforts, even as the Russians, Canadians, and Koreans eyed taking on the project. Now the Trump administration is lending its hand for deploying small modular reactors. The U.S. Trade and Development Agency just announced funding to help the utility MGEN conduct a technical review of U.S. SMR designs, NucNet reported Wednesday.

Sign up to receive Heatmap AM in your inbox every morning:

Despite the American government’s crusade against the sector, Europe is going all in on offshore wind. For a glimpse of what an industry not thrust into legal turmoil by the federal government looks like, consider that just on Wednesday the homepage of the trade publication OffshoreWIND.biz featured stories about major advancements on at least three projects totaling nearly 5 gigawatts:

That’s not to say everything is — forgive me — breezy for the industry. Germany currently gives renewables priority when connecting to the grid, but a new draft law would give grid operators more discretion when it comes to offshore wind, according to a leaked document seen by Windpower Monthly.

American clean energy manufacturing is in retreat as the Trump administration’s attacks on consumer incentives have forced companies to reorient their strategies. But there is at least one company setting up its factories in the U.S. The sodium-ion battery startup Syntropic Power announced plans to build 2 gigawatts of storage projects in 2026. While the North Carolina-based company “does not reveal where it manufactures its battery systems,” Solar Power World reported, it “does say” it’s establishing manufacturing capacity in the U.S. “We’re making this move now because the U.S. market needs storage that can be deployed with confidence, supported by certification, insurance acceptance, and a secure domestic supply chain,” said Phillip Martin, Syntropic’s chief executive.

For years now, U.S. manufacturers have touted sodium-ion batteries as the next big thing, given that the minerals needed to store energy are more abundant and don’t afford China the same supply-chain advantage that lithium-ion packs do. But as my colleague Katie Brigham covered last April, it’s been difficult building a business around dethroning lithium. New entrants are trying proprietary chemistries to avoid the mistakes other companies made, as Katie wrote in October when the startup Alsym launched a new stationary battery product.

Last spring, Heron Power, the next-generation transformer manufacturer led by a former Tesla executive, raised $38 million in a Series A round. Weeks later, Spain’s entire grid collapsed from voltage fluctuations spurred by a shortage of thermal power and not enough inverters to handle the country’s vast output of solar power — the exact kind of problem Heron Power’s equipment is meant to solve. That real-life evidence, coupled with the general boom in electrical equipment, has clearly helped the sales pitch. On Wednesday, the company closed a $140 million Series B round co-led by the venture giants Andreessen Horowitz and Breakthrough Energy Ventures. “We need new, more capable solutions to keep pace with accelerating energy demand and the rapid growth of gigascale compute,” Drew Baglino, Heron’s founder and chief executive, said in a statement. “Too much of today’s electrical infrastructure is passive, clunky equipment designed decades ago. At Heron we are manifesting an alternative future, where modern power electronics enable projects to come online faster, the grid to operate more reliably, and scale affordably.”

A senior scholar at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy on what Trump has lost by dismantling Biden’s energy resilience strategy.

A fossil fuel superpower cannot sustain deep emissions reductions if doing so drives up costs for vulnerable consumers, undercuts strategic domestic industries, or threatens the survival of communities that depend on fossil fuel production. That makes America’s climate problem an economic problem.

Or at least that was the theory behind Biden-era climate policy. The agenda embedded in major legislation — including the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the Inflation Reduction Act — combined direct emissions-reduction tools like clean energy tax credits with a broader set of policies aimed at reshaping the U.S. economy to support long-term decarbonization. At a minimum, this mix of emissions-reducing and transformation-inducing policies promised a valuable test of political economy: whether sustained investments in both clean energy industries and in the most vulnerable households and communities could help build the economic and institutional foundations for a faster and less disruptive energy transition.

Sweeping policy reversals have cut these efforts short. Abandoning the strategy makes the U.S. economy less resilient to the decline of fossil fuels. It also risks sowing distrust among communities and firms that were poised to benefit, complicating future efforts to recommit to the economic policies needed to sustain an energy transition.

This agenda rested on the idea that sustaining decarbonization would require structural changes across the economy, not just cleaner sources of energy. First, in a country that derives substantial economic and geopolitical power from carbon-intensive industries, a durable energy transition would require the United States to become a clean energy superpower in its own right. Only then could the domestic economy plausibly gain, rather than lose, from a shift away from fossil fuels.

Second, with millions of households struggling to afford basic energy services and fossil fuels often providing relatively cheap energy, climate policy would need to ensure that clean energy deployment reduces household energy burdens rather than exacerbates them.

Third, policies would need to strengthen the economic resilience of communities that rely heavily on fossil fuel industries so the energy transition does not translate into shrinking tax bases, school closures, and lost economic opportunity in places that have powered the country for generations.

This strategy to reshape the economy for the energy transition has largely been dismantled under President Trump.

My recent research examines federal support for fossil fuel-reliant communities, assessing President Biden’s stated goal of “revitalizing the economies of coal, oil, gas, and power plant communities.” Federal spending data provides little evidence that these at-risk communities have been effectively targeted. One reason is timing: While legislation authorized unprecedented support, actual disbursements lagged far behind those commitments.

Many of the key policies — including $4 billion in manufacturing tax credits reserved for communities affected by coal closures — took years to move from statutory language to implementation guidance and final project selection. As a result, aside from certain pandemic-era programs, fossil fuel-reliant communities had received limited support by the time Trump took office last year.

Since then, the Trump administration and Congress have canceled projects intended to benefit fossil fuel-reliant regions, including carbon capture and clean hydrogen demonstrations, and discontinued programs designed to help communities access and implement federal funding.

Other elements of the strategy to reduce the country’s vulnerability to fossil fuel decline have fared even worse under the Trump administration. Programs intended to help households access and afford clean energy — most notably the $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund — were effectively canceled last year, including attempts to claw back previously awarded funds. More broadly, the rollback of IRA programs with an explicit equity or justice focus leaves lower-income households more exposed to the economic disruptions that can accompany an energy transition.

By contrast, subsidies and grant programs aimed at strengthening the country’s energy manufacturing base have largely survived, including tax credits supporting domestic production of batteries, solar components, and other key technologies. Even so, the investment environment has weakened. Automakers have scaled back planned U.S. battery manufacturing expansions. Clean Investment Monitor data shows annual clean energy manufacturing investments on pace to decline in 2025, after rising sharply from 2022 to 2024. Whatever one believed about the potential to build globally competitive domestic supply chains for the technologies that will power clean energy systems, those prospects have dimmed amid slowing investment and the Trump administration’s prioritization of fossil fuels.

Perhaps these outcomes were unavoidable. Building a strong domestic solar industry was always uncertain, and place-based economic development programs have a mixed track record even under favorable conditions. Still, the Biden-era approach reflected a coherent theory of climate politics that warranted a real-world test.

Over the past year, debates in climate policy circles have centered on whether clean energy progress can continue under less supportive federal policies, with plausible cases made on both sides. The fate of Biden’s broader economic strategy to sustain the energy transition, however, is less ambiguous. The underlying dependence of the United States on fossil fuels across industries, households, and many local communities remains largely unchanged.